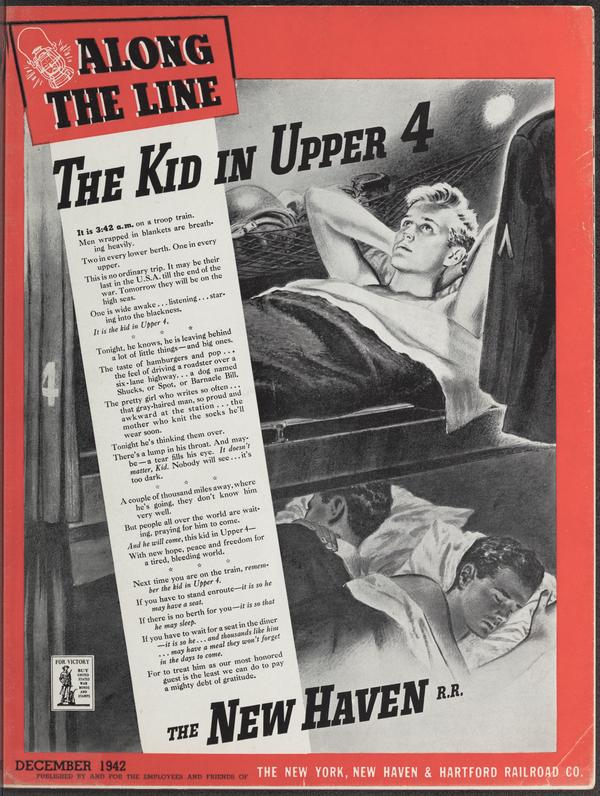

On January 3, 1944, 300 men from Mexico arrived in Connecticut after a journey of 3700 miles which started six days earlier in Mexico City. They were hired as Braceros, or manual labor, to work on the New Haven Railroad for a term of six months through a diplomatic collaboration between the United States and Mexico which provided needed workers for the nation’s railroads during World War II.

The Bracero program had its origins as far back as the 1880s, when Mexican workers were recruited in building the vast network of railroads in the United States. Although later better known as a program for agricultural workers, the Bracero program was an important means to alleviate the shortage of American workers in the railroad industry.

America’s railroads had a crucial role to play during World War II, transporting war materiel from industries that switched production to provide arms, ammunition, and other goods, to transporting soldiers to training camps and points of embarkation. Shipping slowed due to the threat of German submarines off of the U.S. east coast, thus the demand for moving oil and coal fell on the railroads. Civilian passenger service was up due to the rationing of gas for private automobiles. Just at the time the railroads needed more employees to handle this surge in service, they were left short-handed when many of their workers left for the armed forces.

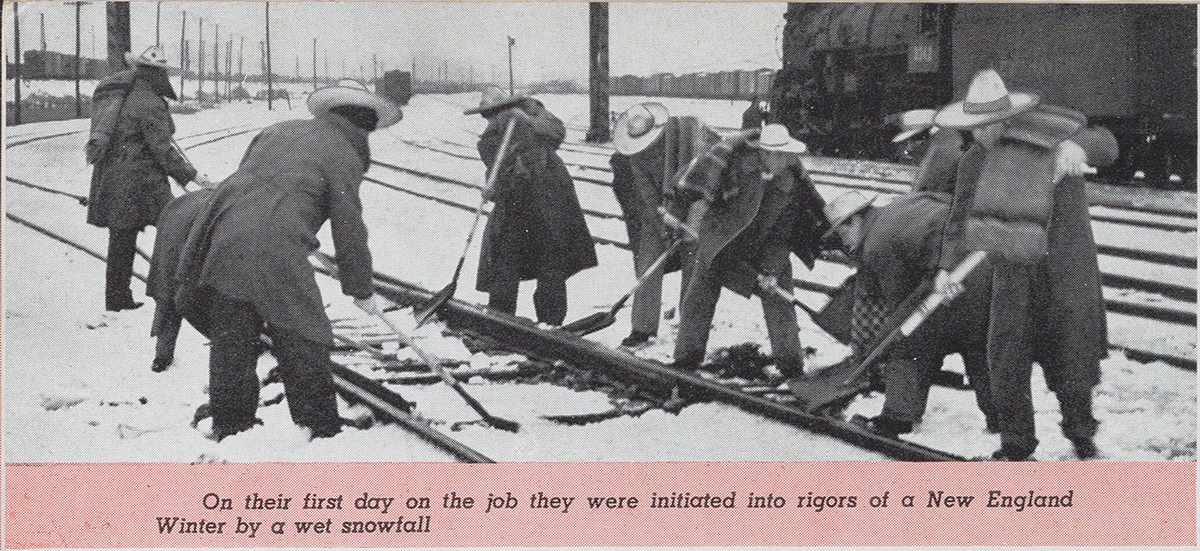

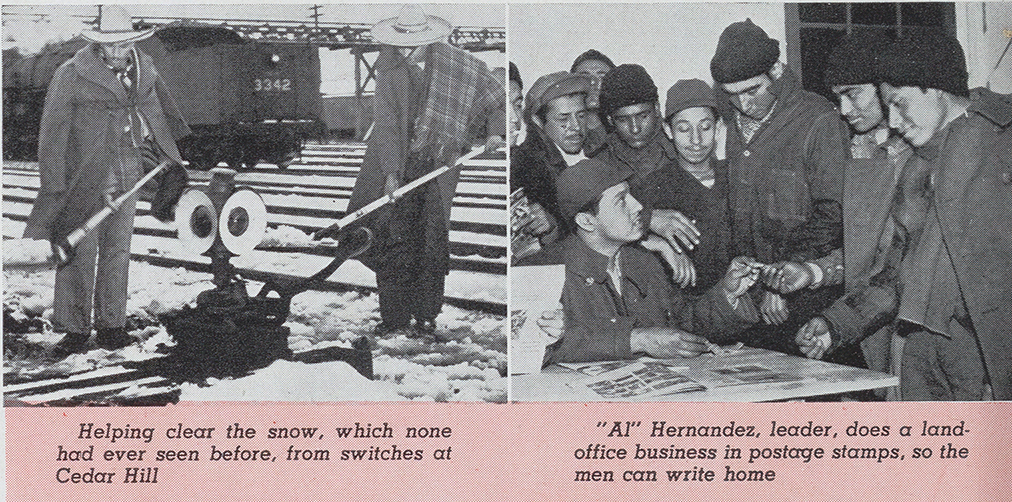

The New Haven Railroad, which provided passenger and freight service throughout southern New England, noted in their 1944 annual report that as of May 1944 over 5500 of their workers left for the armed services; that number rose to 7200 by the war’s end. Although the railroad was able to hire women to make up some of the lost workers, they relied on the Bracero program for the unskilled labor they needed to clean ash pits and fires, load coal, shovel sand, remove snow from tracks, and many other manual labor jobs.

Beginning in Spring 1943 the Bracero program recruited over 100,000 Mexican men to work for thirty railroads throughout the United States. While most of the men were recruited for railroads in the Midwest, South and West, over the two-and-a-half-year period of the program the New Haven Railroad received approximately 1000 workers.

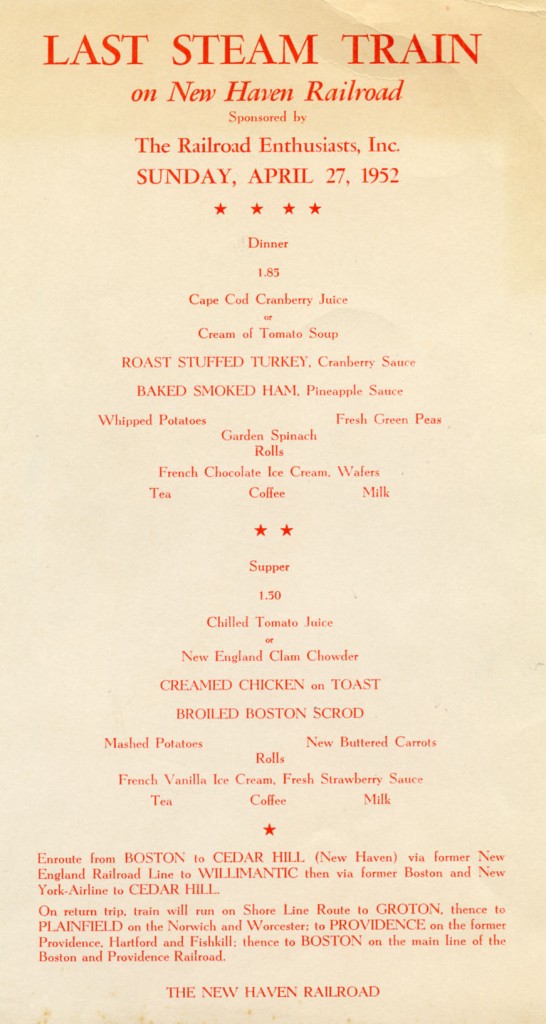

The Mexican men, with an average age of 28, were dispersed among several locations in the New Haven Railroad area; in Connecticut they worked at engine houses and railyards including Cedar Hill in New Haven, East Greenwich and Guilford. The contracts drawn up between the U.S. and Mexican governments stipulated that the men would receive the same rate of pay as American workers and work a ten-hour day, six days a week.

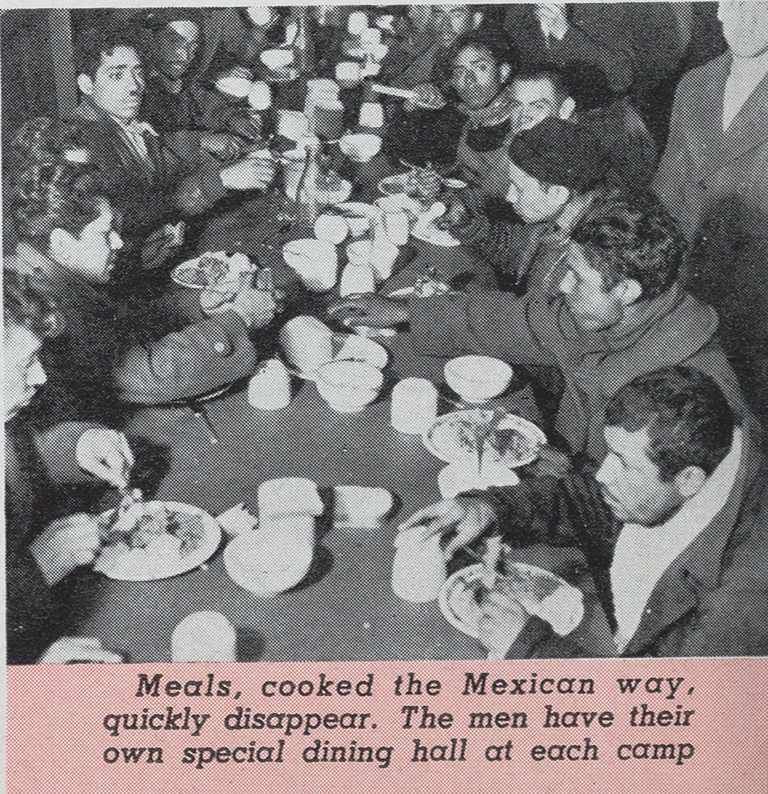

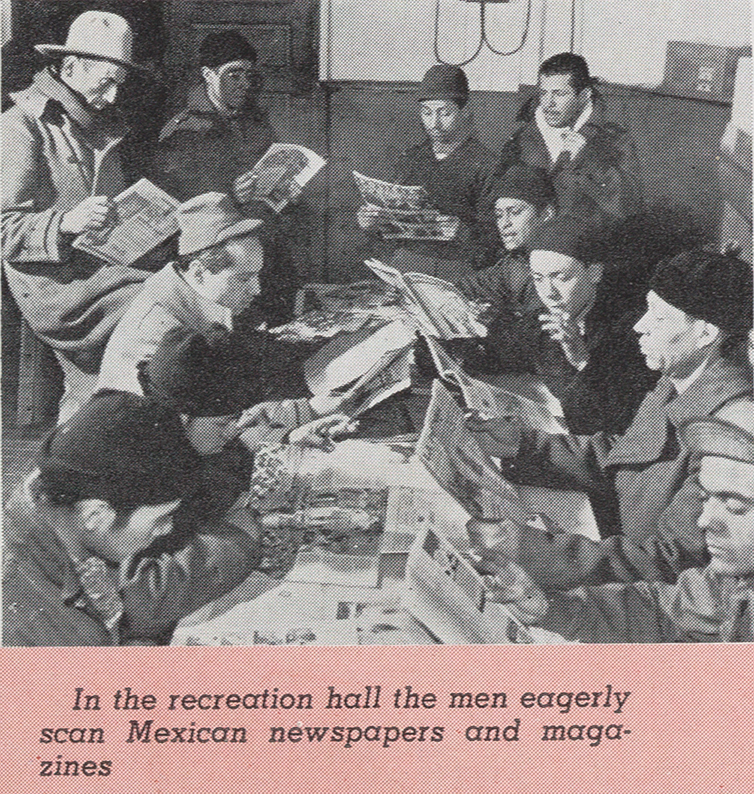

In an article that ran in the February 1944 issue of the railroad’s employee magazine, Along the Line, it was noted that the men were given warm clothing suitable for hard industrial work in cold climates. They were housed in a dormitory in North Haven and chefs were brought from Mexico to accommodate the men’s eating preferences. Priests were brought in for Sunday services. It was also noted that most of the men sent their pay back to their families in Mexico.

The men were given a warm welcome by the railroad, with the acknowledgement in Along the Line that “…it takes plenty of courage voluntarily to break off home ties, to leave families three thousand miles away, in an endeavor to improve their living conditions. It was the same spirit which in earlier years guided immigrants to America and resulted in the building of our great nation. We salute our Mexican friends, as fellow employees, thank them for their cooperation in coming, and express the hope that they will enjoy their stay with us. Bien Venido, Amigos!”

By the end of the war, with the return of almost 90% of the New Haven Railroad’s workforce from the armed forces, the contracts for the Mexican Braceros expired and the men returned home.