The following guest blog post is by Golan Moskowitz, a doctoral candidate at Brandeis University, where he received a joint M.A. in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies and Women’s and Gender Studies. Mr. Moskowitz is the 2016 recipient of the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant, an annual research grant awarded to scholars to encourage use of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection. Mr. Moskowitz is also a visual artist with a B.A. in Art from Vassar College.

Children’s books are serious business. So thought the late Maurice Sendak (1928-2012), who believed that the apparent simplicity of the children’s book – along with children’s talent for intuition and interpretation – made it an ideal form for burying complex messages. Among the most serious of artists to ever write children’s books, Sendak offered messages about how the wider society might neglect or threaten unusual individuals, but also how those individuals might harness fantasy, animal strength, and improvisation to endure and survive. As a recipient of the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant, I had the privilege of studying several of the collections in Archives and Special Collections, which enriched my understanding of Sendak’s relationships with children’s authors Ruth Krauss (1901-1993) and James Marshall (1942-1992), as well as with children’s literature scholar Francelia Butler (1913-1998). Sendak absorbed much of Krauss’s critical stance toward social conventions of constrained gender and sexuality. He found solidarity with Marshall’s good-natured cynicism and candidly shared some of his controversial intentions and interesting underlying beliefs with Butler.

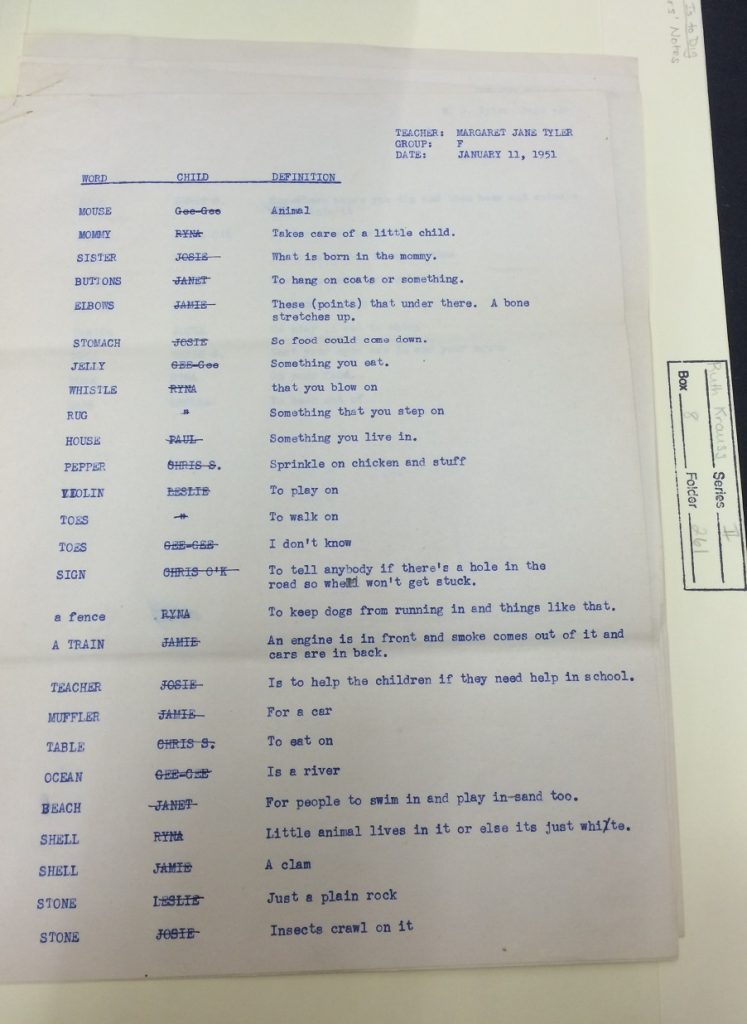

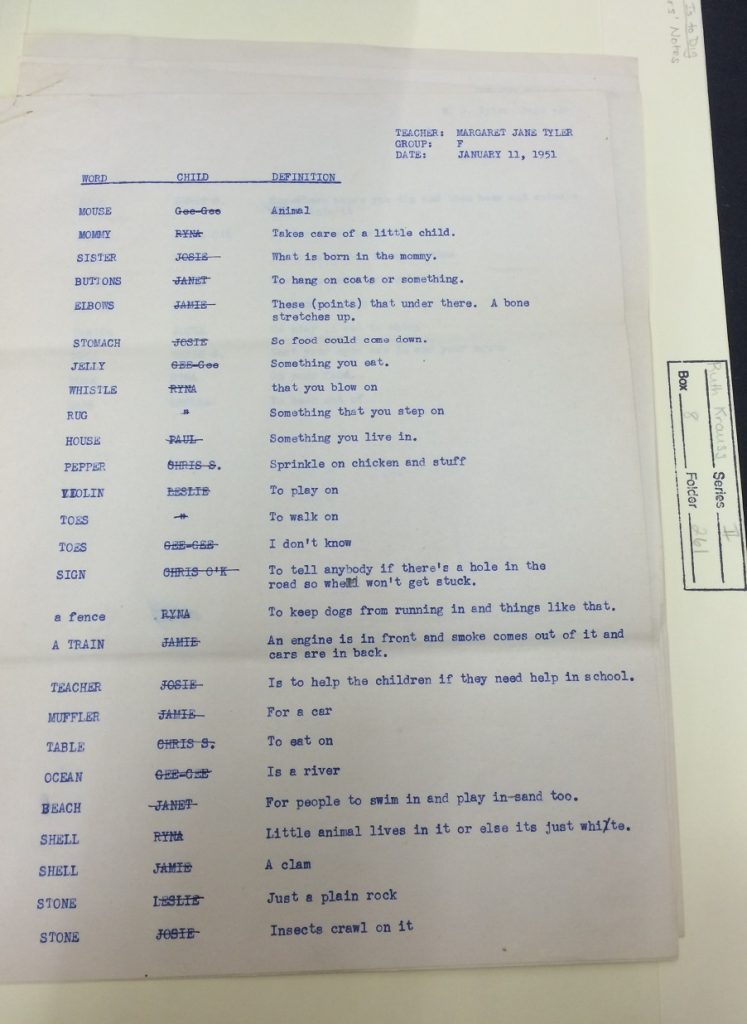

Selling over eighty thousand copies by its fifth year in publication, A Hole Is to Dig (1952), children’s literature scholar Leonard S. Marcus writes, first established the twenty-four-year-old Sendak as “a talent to reckon with.”[1] To write the book, which was published as “a series of definitions reflecting childlike logic (many supplied by children themselves),”[2]  Krauss studied children at the progressive Bank Street School, collecting definitions offered to her by the toddlers and preschoolers on 3×5-inch index cards.[3] She assembled and typed lists of these definitions; some that did not make it to the final version included: the stomach is a “food factory,” a match is “to light cigarette,” a chimney is “Smoke comes up and Santa Claus comes down,” and a shell is “Lobsters – snap your hand off.”[4] The Krauss papers also include hand-written comments on Sendak’s sketches for the book. The author advised against pictures of children sitting on books (to get higher up), as books should not be treated “too rough.” She also asked that for the caption, “dogs are to kiss people,” Sendak include among the other children being licked (each by a different dog) “one polygamous child with many dogs.” [5]

Krauss studied children at the progressive Bank Street School, collecting definitions offered to her by the toddlers and preschoolers on 3×5-inch index cards.[3] She assembled and typed lists of these definitions; some that did not make it to the final version included: the stomach is a “food factory,” a match is “to light cigarette,” a chimney is “Smoke comes up and Santa Claus comes down,” and a shell is “Lobsters – snap your hand off.”[4] The Krauss papers also include hand-written comments on Sendak’s sketches for the book. The author advised against pictures of children sitting on books (to get higher up), as books should not be treated “too rough.” She also asked that for the caption, “dogs are to kiss people,” Sendak include among the other children being licked (each by a different dog) “one polygamous child with many dogs.” [5]

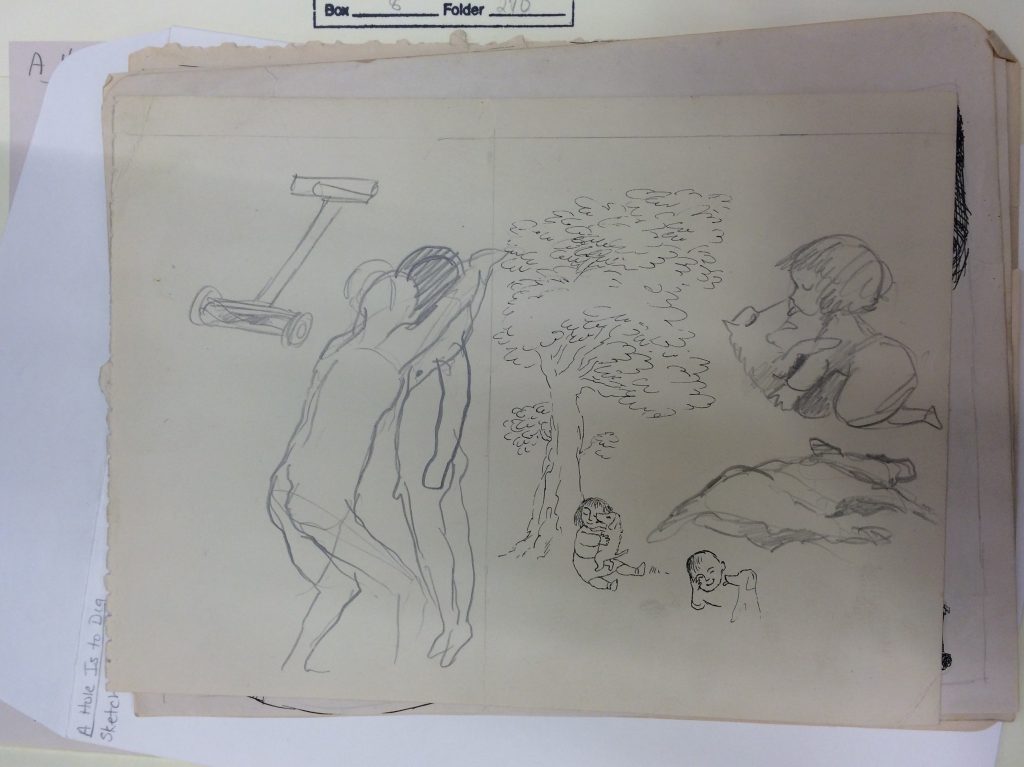

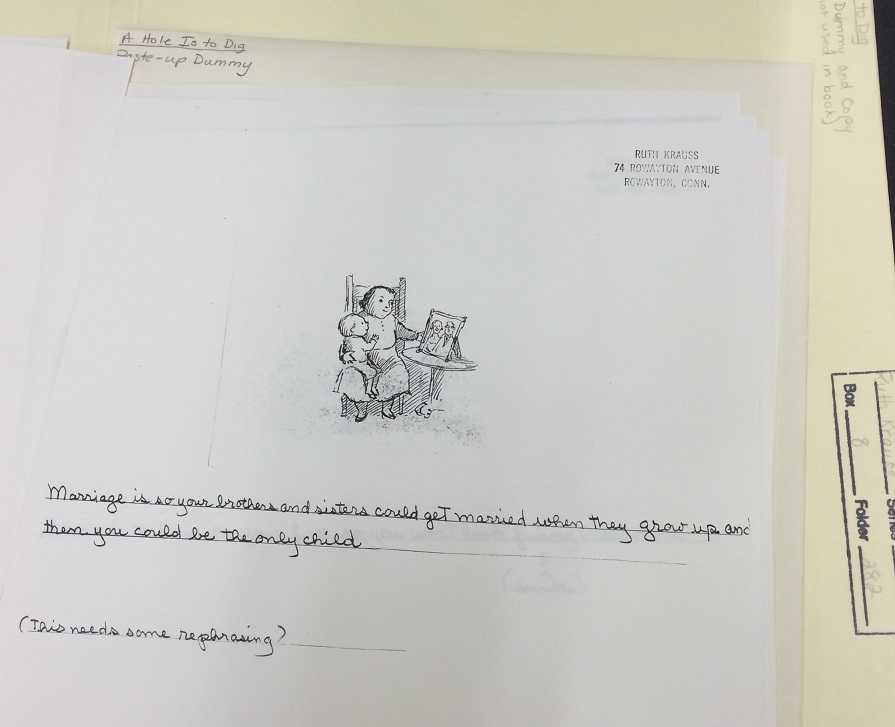

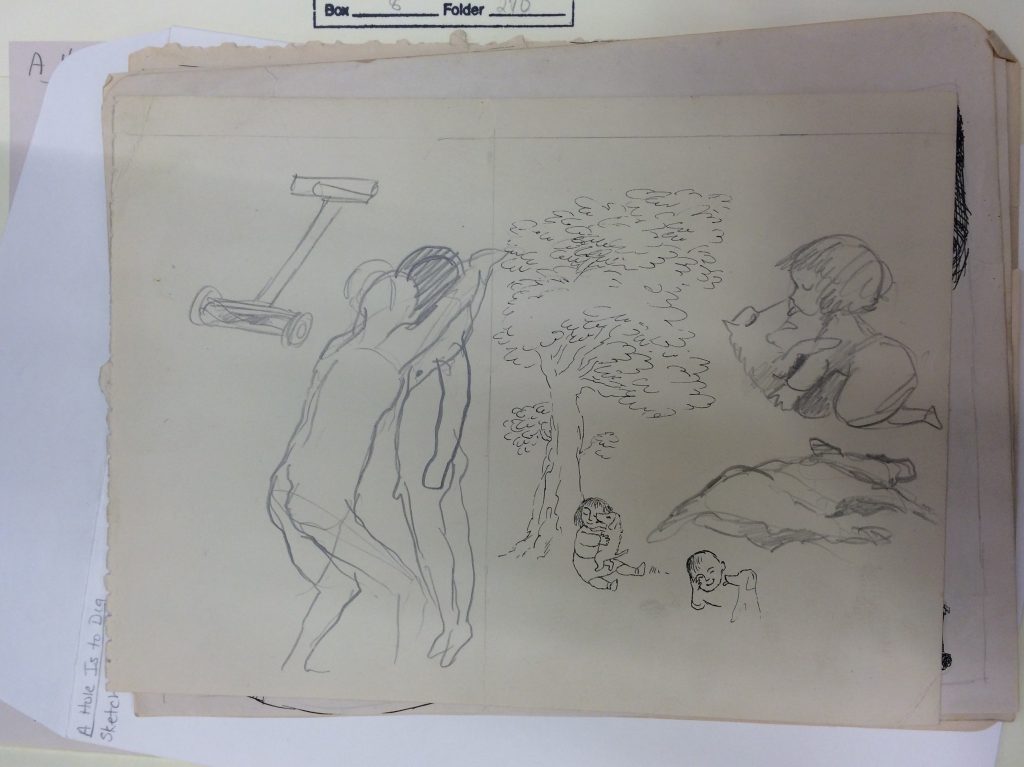

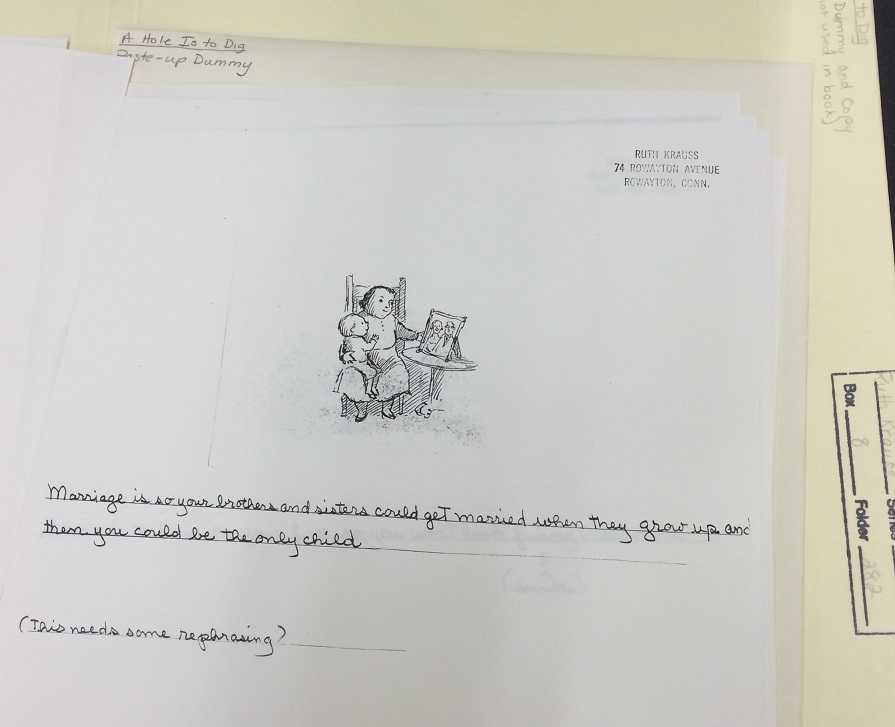

Krauss’s input sheds additional light on the young Sendak’s forming artistic values. To better access his own vitality and humor, he was learning to revere books as sacred objects while demystifying the dominant, often clichéd narratives of the social order. [6] Extraneous doodles in Sendak’s layout sketches for A Hole Is to Dig reveal the young artist’s self-liberating impulse during his work on the book. One sketch depicts two nude figures with a relaxed line, one leaning on the other, genitalia exposed. Beside them, a small girl reclines with a dog, kissing the dog on the mouth. [7] Such free-flowing sensuality surely helped Sendak resist the self-policing of a closeted gay son of Eastern European Jewish immigrants – an essential exercise for an artist to strengthen honest expression and resist cliché. Sendak applied such subversive, child-like flow to the close relationships of his own life, including with  Krauss, whom he loved dearly. When he later visited her on her deathbed, he kissed the withering writer on her lips with tongue, eliciting a giggle that emanated the mirth and energy that was sadly fading from her body.[8] Sendak might have seen himself as something of a playfully welcomed intruder and an anomaly in the social matrix of heterosexuality – not belonging, but carving out a relational position for himself with play and affection. One of his unused sketches for A Hole Is to Dig depicts a child on his mothers lap with the caption, “Marriage is so your brothers and sisters could get married when they grow up and then you could be the only child.” A comment below reads, “This needs some

Krauss, whom he loved dearly. When he later visited her on her deathbed, he kissed the withering writer on her lips with tongue, eliciting a giggle that emanated the mirth and energy that was sadly fading from her body.[8] Sendak might have seen himself as something of a playfully welcomed intruder and an anomaly in the social matrix of heterosexuality – not belonging, but carving out a relational position for himself with play and affection. One of his unused sketches for A Hole Is to Dig depicts a child on his mothers lap with the caption, “Marriage is so your brothers and sisters could get married when they grow up and then you could be the only child.” A comment below reads, “This needs some  rephrasing.” [9]

rephrasing.” [9]

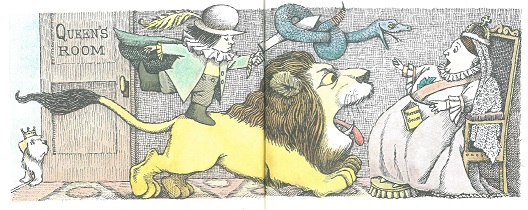

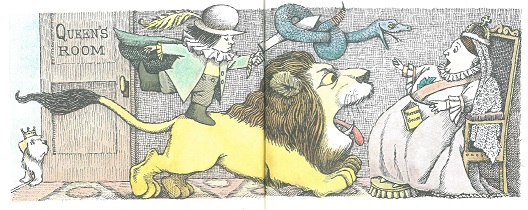

Sendak viewed illustration as a means for illuminating hidden interpretations or expressing his own emotional truth between the lines of the text. He enjoyed the illustrator’s prerogative, for example, in his Hector Protector (1965), which enlivens a short, ambiguous rhyme: “Hector Protector was dressed all in green; Hector Protector was sent to the Queen. The Queen did not like him, Nor more did the King; So Hector Protector was sent back again.” Sendak’s illustration of the poem creates a face-off between a scandalized, rotund Victorian queen reading Mother Goose and a wild boy, phallus erect in the form of an extended sword, riding on the back of a masculine lion. A serpent tangled around Hector’s sword in the shape of two coiled circles and a lunging head further emphasizes the phallic element (pp.15-16) [image at top]. One young male reader responded to the drawing with a letter to Sendak, asking, “When I grow up will mine be as big as Hector’s?” Describing his drawings for this book as a sort of revenge against critics who found his work too explicit for children, Sendak admitted, “I very consciously, obviously used and played with the snake in just those ways. Those pictures are so obvious it is embarrassing.” [10]

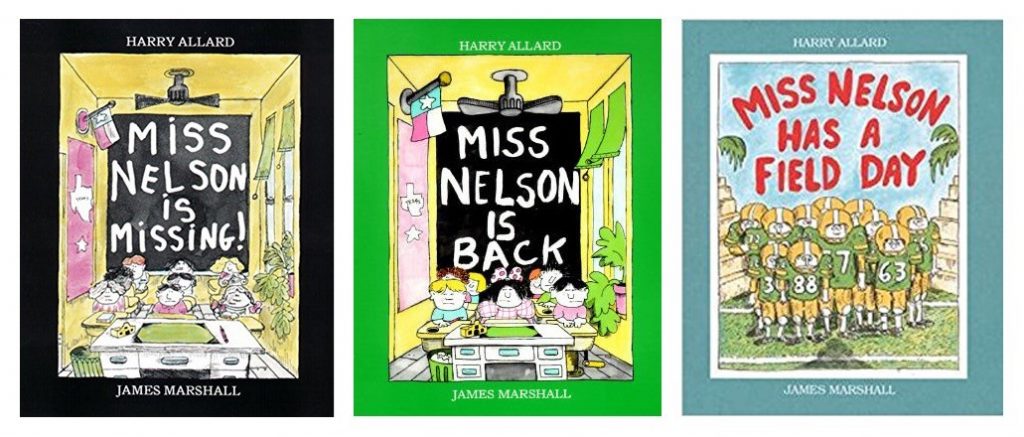

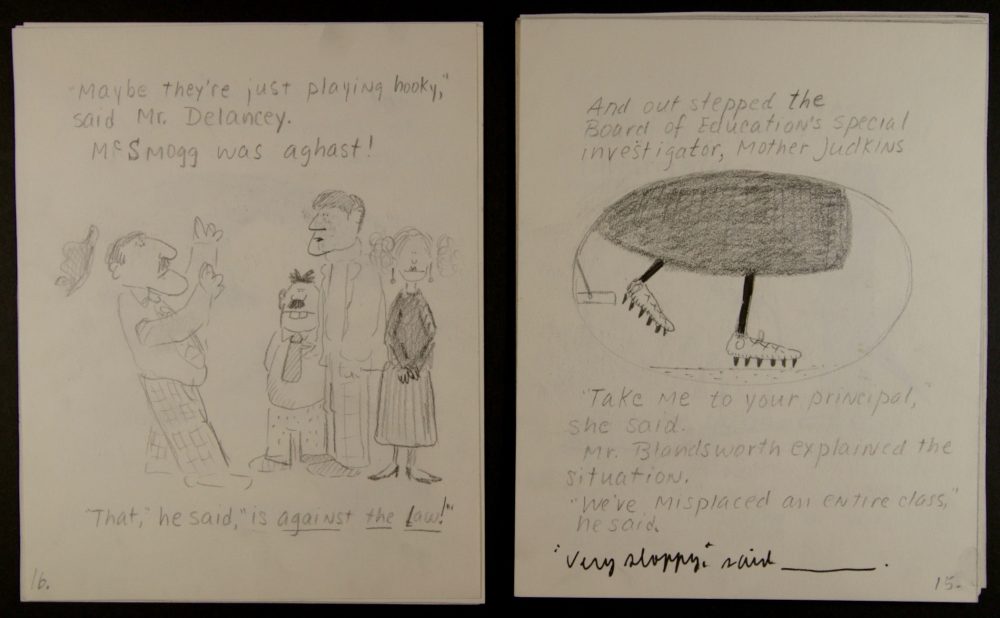

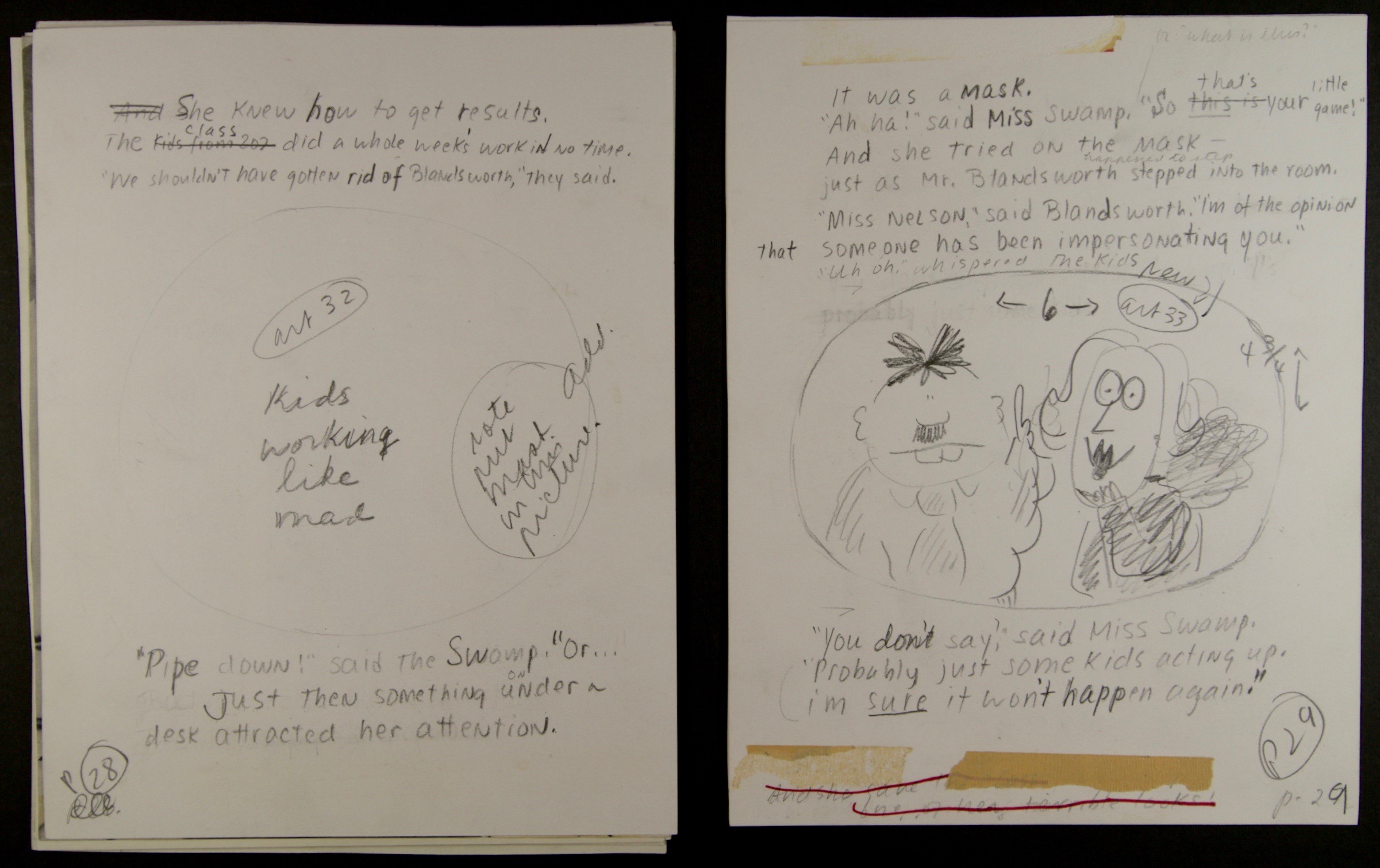

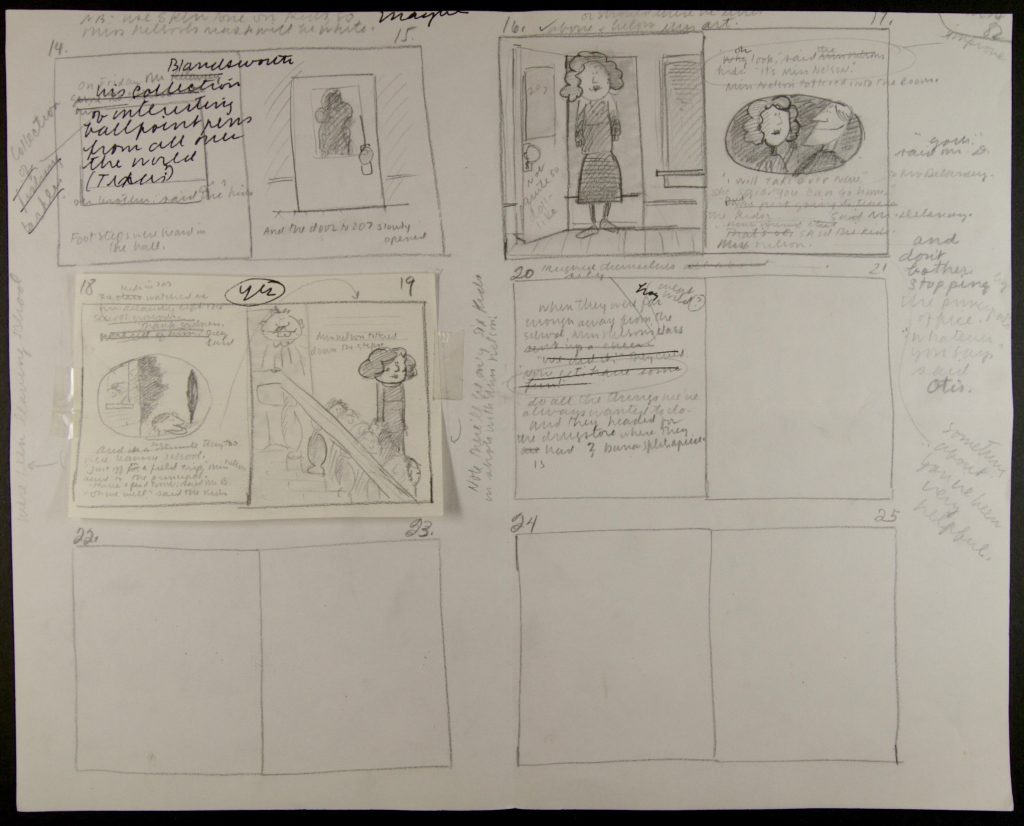

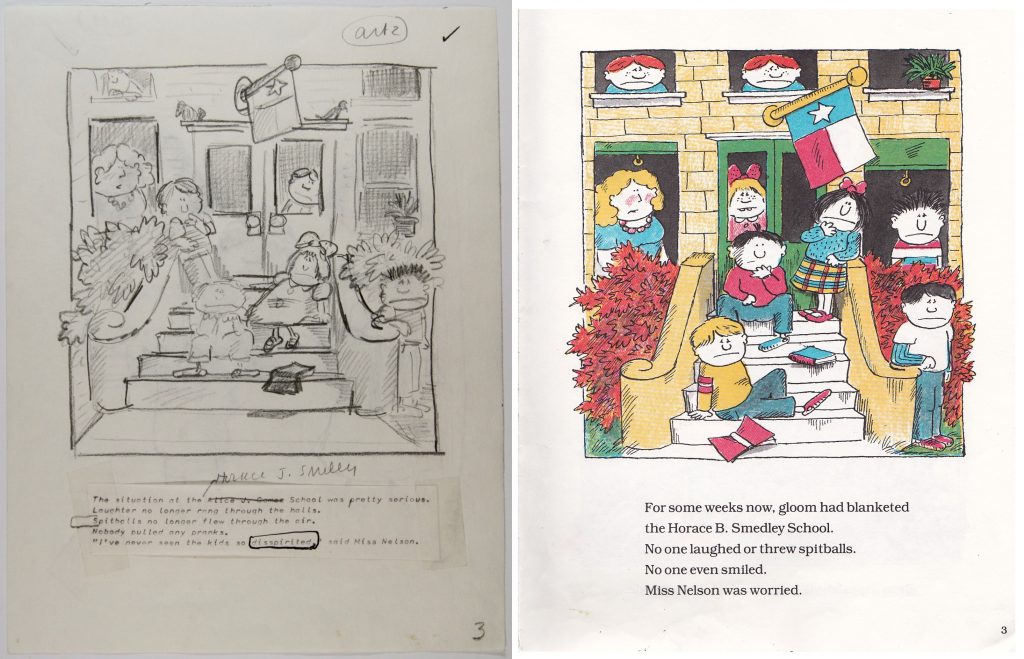

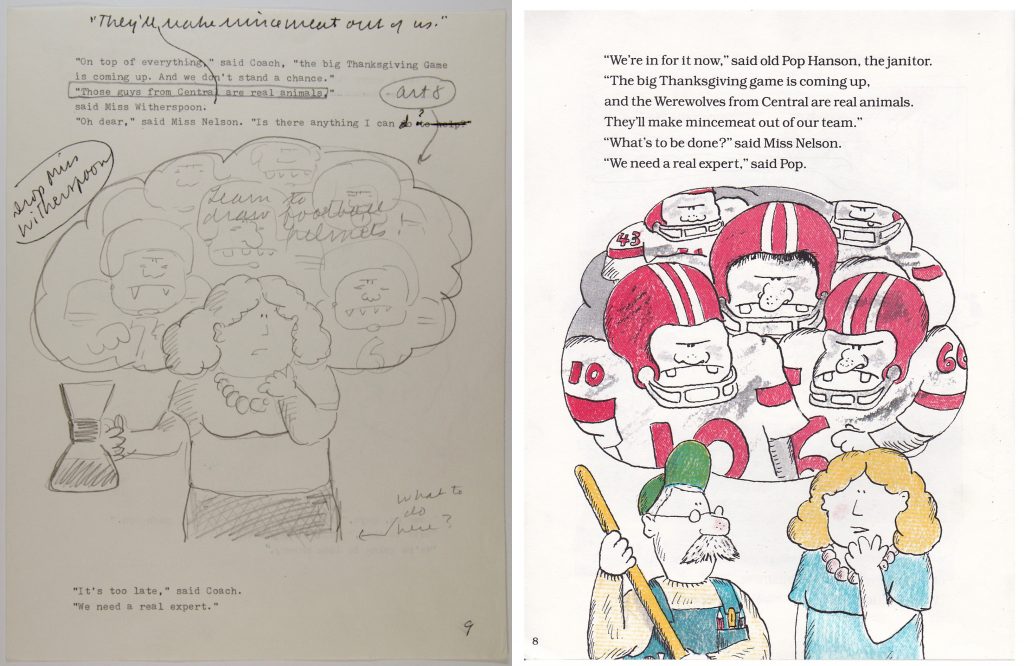

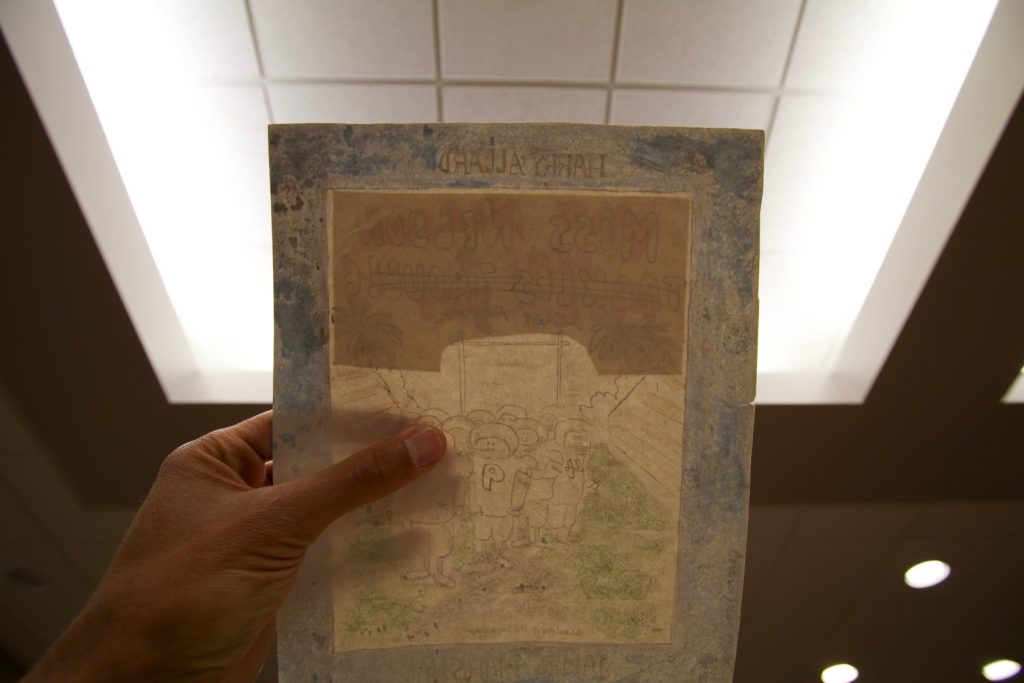

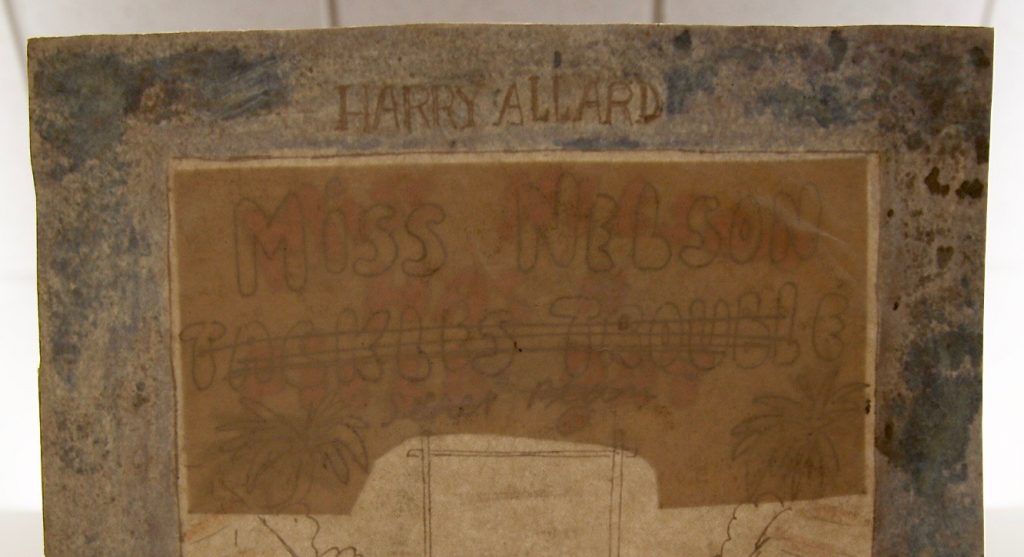

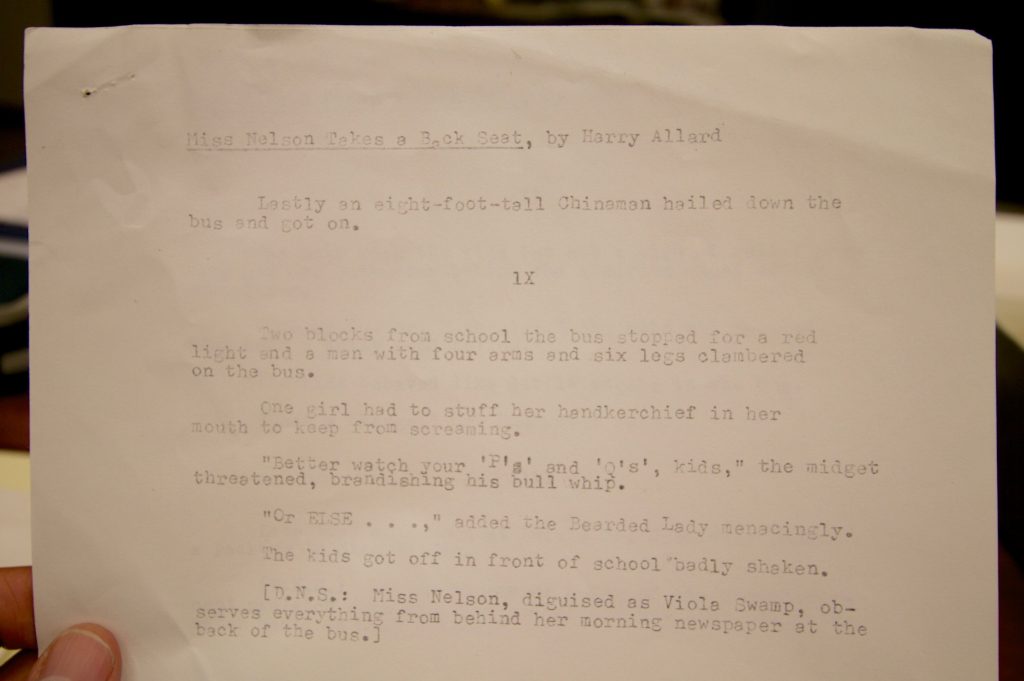

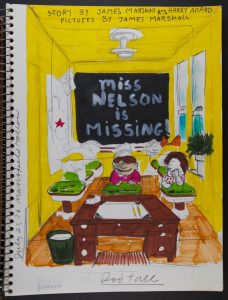

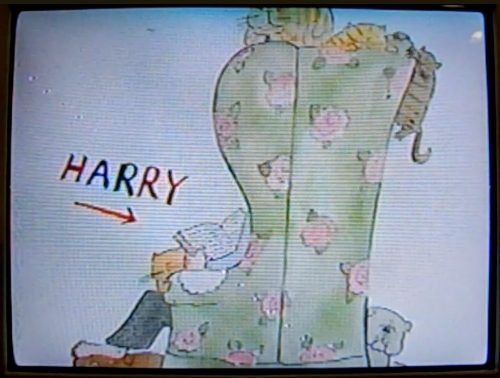

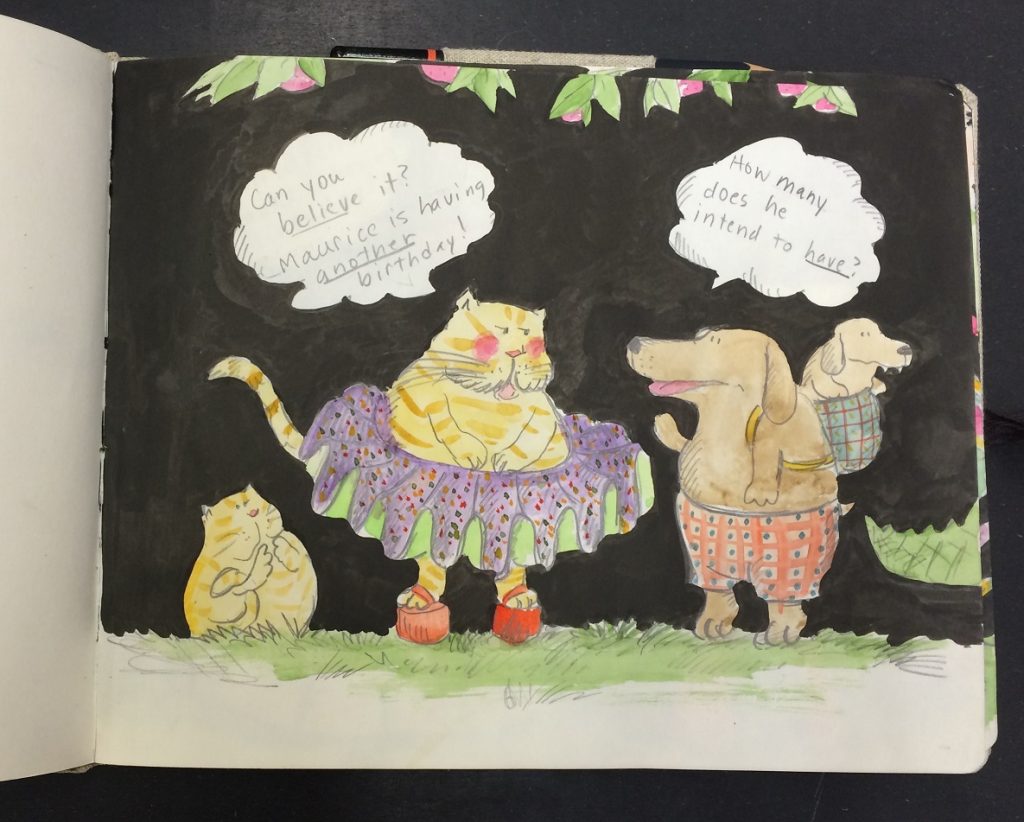

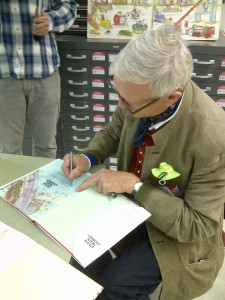

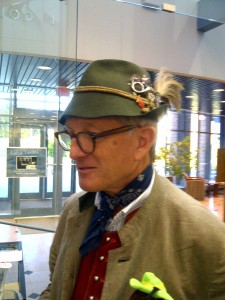

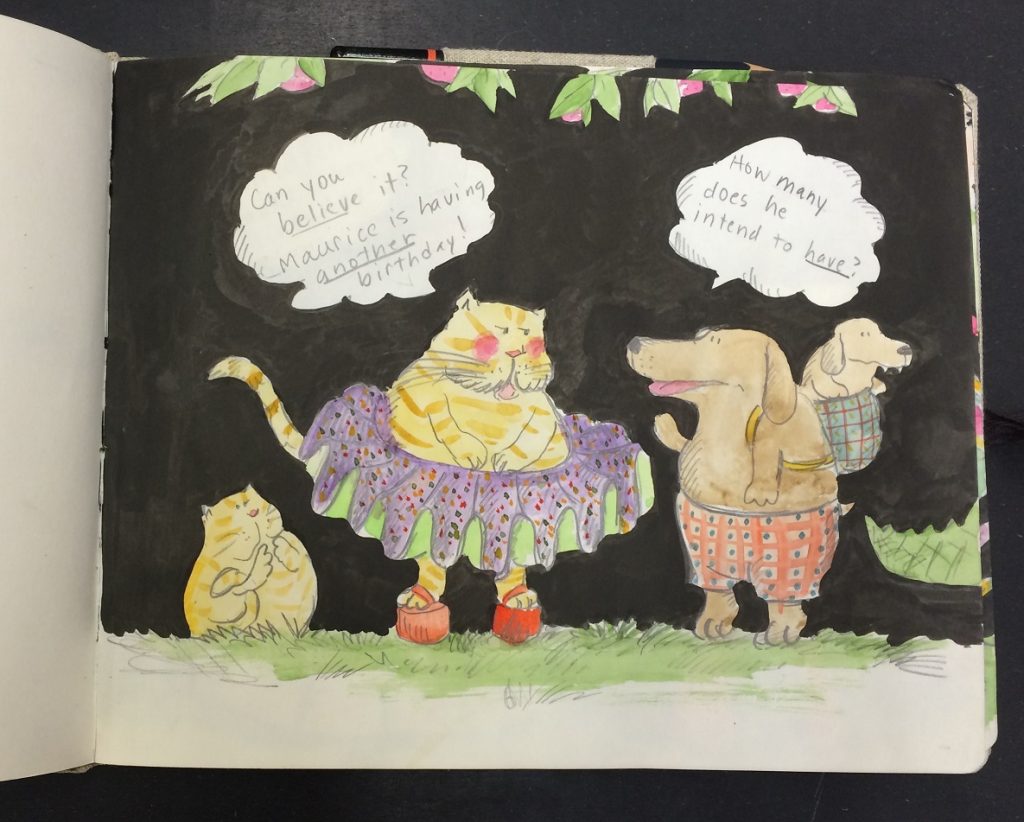

Sendak’s dark sense of humor and questioning of social boundaries was shared by artist and writer James Marshall. Sarcasm and morbid jokes helped them protect themselves against the potential pain that could result from clashing so starkly with aspects of mainstream, bourgeois culture. Both artists were gay men in an era that predated mainstream acceptance of LGBTQ people, especially in the field of children’s literature. A handmade birthday book [11] from Marshall to Sendak brims with delightful snark and suggests a level of solidarity that was rare for the reserved Sendak – a man who once confessed, “My rough time comes when [a] book is over and then I have to go to dinner with people and I am expected to go uptown and act like a grown-up at a party.”[12] Marshall and Sendak, however, much enjoyed their visits with each other.

Sendak’s dark sense of humor and questioning of social boundaries was shared by artist and writer James Marshall. Sarcasm and morbid jokes helped them protect themselves against the potential pain that could result from clashing so starkly with aspects of mainstream, bourgeois culture. Both artists were gay men in an era that predated mainstream acceptance of LGBTQ people, especially in the field of children’s literature. A handmade birthday book [11] from Marshall to Sendak brims with delightful snark and suggests a level of solidarity that was rare for the reserved Sendak – a man who once confessed, “My rough time comes when [a] book is over and then I have to go to dinner with people and I am expected to go uptown and act like a grown-up at a party.”[12] Marshall and Sendak, however, much enjoyed their visits with each other.

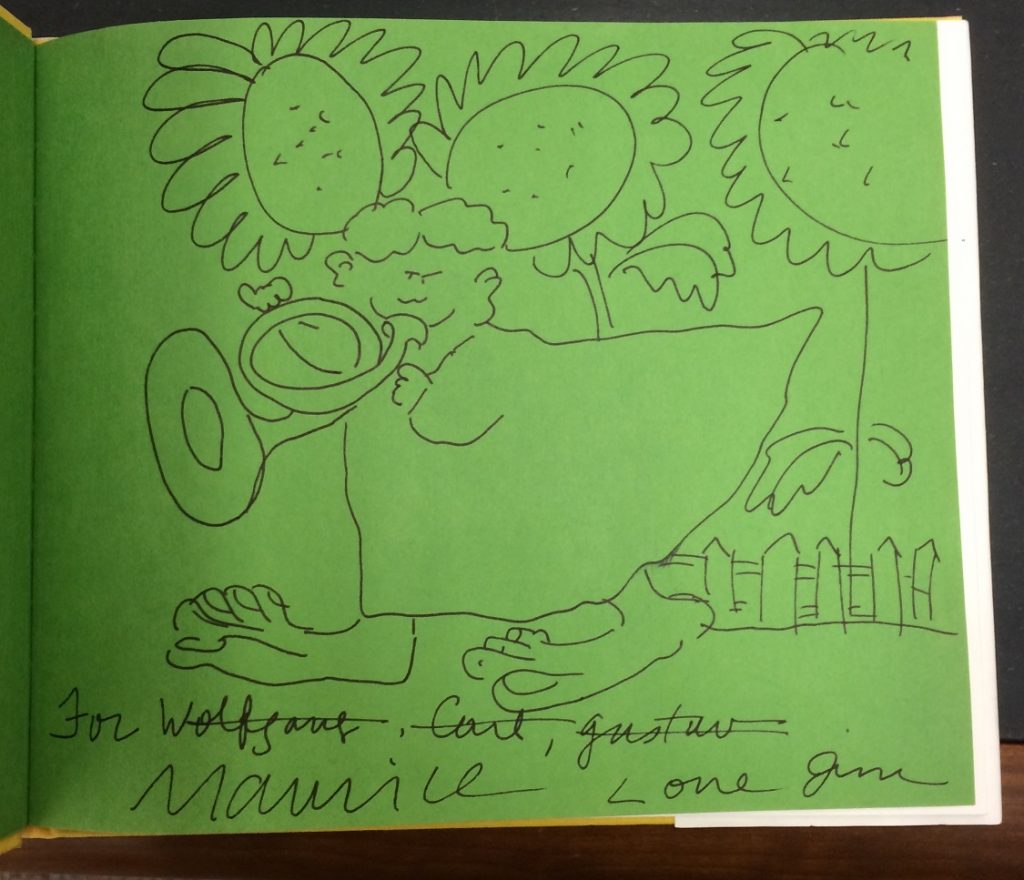

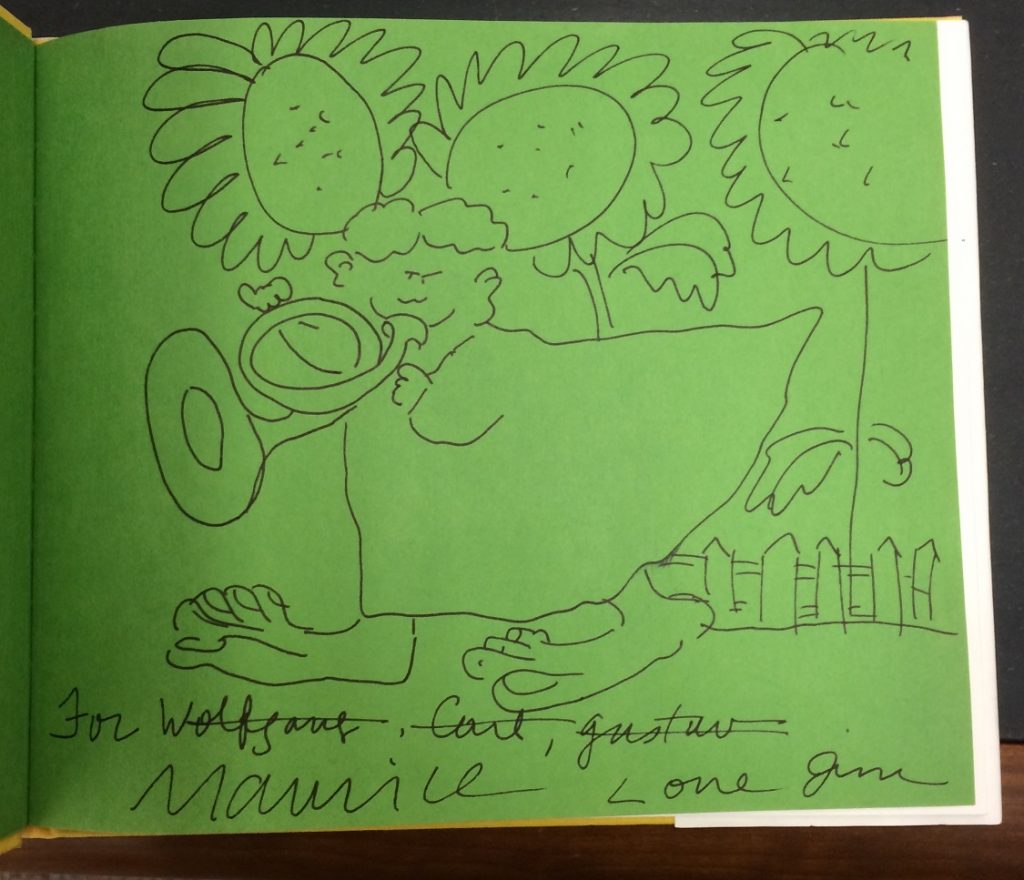

Marshall seems to have appreciated the latter’s identification with German high culture, playfully inscribing a copy of one of his books to Sendak “For Wolfgang, Carl, Gustav Maurice.” He accompanied the inscription with a drawing of a boy blowing a horn, dressed in the German Romantic style of Sendak’s Outside Over There (1981). [13] Like Sendak’s proclivity for empathetically illustrating pigs, even coming from a culture that treated swine as abject and impure (Bumble-Ardy, House of Sixty Fathers, Swine Lake, etc.), Sendak’s identification with Germany may have reflected his own sense of difference or rejection. Germany and its art were queer love objects for a WWII-era Jewish child of an Eastern European, Yiddish-speaking family – much of which was destroyed in the Holocaust. Like his homosexuality and his veneration of childhood and artistic pursuits, Sendak’s identification with German culture signified a socially rebellious impulse to sometimes  honor his own personal tastes and sensory drives even against the expectations of the wider public and of his family heritage. But as children, LGBTQ people, those resisting acculturation, and others who follow their inner drives understand, Sendak knew early on that integrity to an unusual calling could cost him the privilege of social belonging, even as it offered distinction. An unused panel by Sendak for A Hole Is to Dig paired the caption “Lonely is to be like a star” with the image of a solitary boy staring up at a star.

honor his own personal tastes and sensory drives even against the expectations of the wider public and of his family heritage. But as children, LGBTQ people, those resisting acculturation, and others who follow their inner drives understand, Sendak knew early on that integrity to an unusual calling could cost him the privilege of social belonging, even as it offered distinction. An unused panel by Sendak for A Hole Is to Dig paired the caption “Lonely is to be like a star” with the image of a solitary boy staring up at a star.

My research at the Dodd Center adds important elements to my dissertation, which explores how Sendak contributed to shifting conceptions of modern childhood in relation to his own boyhood internalization of his immigrant family’s losses in Europe during WWII and the years surrounding it, as well as his “queer” difference as a gay, physically frail artist. The project examines Sendak’s articulations of how marginalized human beings – including refugees, traumatized individuals, and LGBTQ people – navigate a social order that neglects or threatens them. I am grateful to Melissa Watterworth Batt and Kristin Eshelman for ably administering the Dodd Research Center’s collections, generously facilitating my visit, and making it such a pleasant and productive one.

-Golan Moskowitz

[1] Leonard S. Marcus, “Chapter I: The Artist and His Work: Fearful Symmetries: Maurice Sendak’s Picture Book Trilogy and the Making of an Artist,” Maurice Sendak: A Celebration of the Artist and His Work, ed. Leonard S. Marcus (Abrams, 2013) 18.

[2] Vincent Giroud and Maurice Sendak (curators), Sendak at the Rosenbach, exhibition catalog, Rosenbach Museum, April 28-Oct. 30, 1995, 8.

[3] Marcus (2013) 18.

[4] Ruth Krauss, list collected from the class of Dorothy Walker, Group G., January 12, 1951. Ruth Krauss Papers, Series 2, Box 8, Folder 261: “A Hole is to Dig Teachers’ Notes, Jan 11-12, 1951,” Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut.

[5] For unknown reasons, the published drawing does not accommodate this request. Ruth Krauss, letter to Sendak (“Thursday,” n.y.), Ruth Krauss Papers, Correspondence to Sendak, Series 1, Box 2, Folder 63. Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut.

[6] Typed definitions from the class of Margaret Jane Tyler, Group F, January 11, 1951, Ruth Krauss Papers, Series 2, Box 8, Folder 261, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut.

[7] Maurice Sendak, layout pencil sketch for A Hole Is to Dig, Ruth Krauss Papers, Series 2, Box 8, Folder 270: A Hole is to Dig Layout Sketches by Maurice Sendak, n.d., Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut.

[8] “‘Don’t assume anything’: A Conversation with Maurice Sendak Philip Nel,” 2001, rpt. in Conversations with Maurice Sendak, ed. Peter C. Kunze (Jackson: U. Press of Mississippi, 2016) 138.

[9] Ruth Krauss Papers, Series 2, Box 8, Folder 282: “A Hole is to Dig Cover Paste-up Dummy and Copy (Images not used in book), n.d.,” Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut.

[10] Maurice Sendak, Interview with Francelia Butler’s children’s literature class, April 1976, 19. Francelia Butler Papers, Series 2, Box 9, Folder: “Sendak, Maurice – Children’s Literature,” Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut.

[11] James Marshall, birthday book for Maurice Sendak, Maurice Sendak Collection of James Marshall, Box 2, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut.

[12] Maurice Sendak, Interview with Francelia Butler’s children’s literature class, April 1976, 26. Francelia Butler Papers, Series 2, Box 9, Folder: “Sendak, Maurice – Children’s Literature,” Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut.

[13] James Marshall inscription to Maurice Sendak in Sendak’s copy of James Marshall, The Stupids Die (1981), Maurice Sendak Collection of James Marshall, Box 1, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut.

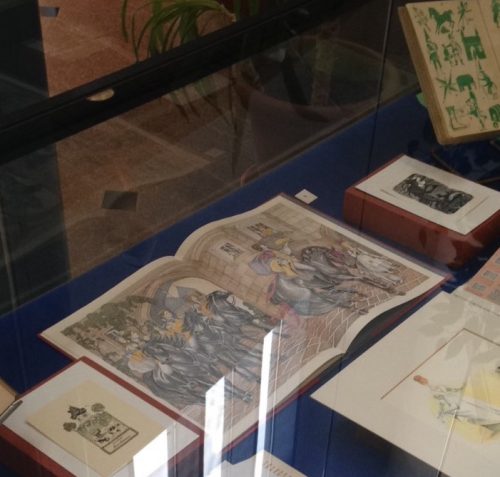

The following is an excerpt of an exhibition essay by Nicolas Ochart, Student Exhibitions Intern in Archives and Special Collections, for an exhibition currently on view in the McDonald Reading Room in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. This semester, Nicolas is responsible for conceiving and developing small-scale exhibitions that highlight archival material found in the collections. He hopes to pursue professional curatorial work in an effort to promote the work and experiences of marginalized and underrepresented communities in the United States. In December, Nicolas will receive his B.A. in Art History from the University of Connecticut.

The following is an excerpt of an exhibition essay by Nicolas Ochart, Student Exhibitions Intern in Archives and Special Collections, for an exhibition currently on view in the McDonald Reading Room in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. This semester, Nicolas is responsible for conceiving and developing small-scale exhibitions that highlight archival material found in the collections. He hopes to pursue professional curatorial work in an effort to promote the work and experiences of marginalized and underrepresented communities in the United States. In December, Nicolas will receive his B.A. in Art History from the University of Connecticut. The collection’s extensive holdings have made the University of Connecticut a nexus for scholars and children’s book writers and illustrators across the nation interested in studying the literary and aesthetic qualities of the form. In an effort to support and encourage study of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, Archives and Special Collections have developed a number of awards for researchers, including the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant and the James Marshall Fellowship. Grantees and Fellows have written on such varied topics as queer American Jewishness in the art and writings of Maurice Sendak, as well as influences of modernism and fashion design in the work of Esphyr Slobodkina. Aspiring and established authors and illustrators have also looked at papers by James Marshall, Natalie Babbitt, Tomie dePaola, and Eleanor Estes for guidance in their own practice.

The collection’s extensive holdings have made the University of Connecticut a nexus for scholars and children’s book writers and illustrators across the nation interested in studying the literary and aesthetic qualities of the form. In an effort to support and encourage study of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, Archives and Special Collections have developed a number of awards for researchers, including the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant and the James Marshall Fellowship. Grantees and Fellows have written on such varied topics as queer American Jewishness in the art and writings of Maurice Sendak, as well as influences of modernism and fashion design in the work of Esphyr Slobodkina. Aspiring and established authors and illustrators have also looked at papers by James Marshall, Natalie Babbitt, Tomie dePaola, and Eleanor Estes for guidance in their own practice.