Glastonbury, Conn., English teacher David Polochanin was recently awarded the James Marshall Fellowship, as he pursues to write young adult literature as part of a yearlong sabbatical. During his research, he will write an occasional series of blog posts, based on his observations and insights relating to the contents of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection at the University of Connecticut. This is the second in the series.

Blog post 2: On The Psychology Of Writing

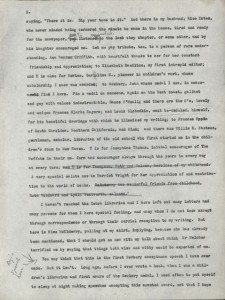

“You may think that this is the first Newbery acceptance speech I have ever made. But it isn’t. Long ago, before I ever wrote a book, when I was a children’s librarian and first aware of the Newbery Medal, I used to often put myself to sleep at night making speeches accepting this coveted award. These speeches were all exceptionally good and I wish I could remember them now. After I started writing, I stopped this pleasant habit, for my mind busied itself with wayward excursions creating chapters for… books.”

Excerpt from Eleanor Estes’ 1952 Newbery Medal speech for her book Ginger Pye

Within the publishing industry, there is a genre subset that exists mainly because of the uncertainty, mystery, and pressure that all writers face – the self-help writing guide. New books are sold every year, offering expert advice on such writerly, often impossible, things as how to summon the muses, where characters come from, the best ways to begin and end a story, if outlining is necessary for everyone, as if these were insider secrets only known to a few. Still, we learn that some authors write early in morning; others late at night. Some claim the best ideas come while taking long walks; others write what they dream and form stories around that.

To prove the marketability of such books, there is still a shelf at your local Barnes and Noble and the UConn Co-op reserved for such titles as John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction, Ray Bradbury’s Zen In The Art Of Writing, Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir Of The Craft, Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down the Bones: Freeing The Writer Within, Anne Lamott’s Bird By Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, and Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, among others.

As a writer, especially at the beginning, during those fledgling phases when you’ve got 40 pages of something and it isn’t going so well, it’s hard not to look at these books. They are indeed tempting to read. Teachers at the college level routinely assign them as class texts, and the content is often useful, if not entertaining. I’ve bought a bunch of them myself, and every now and then, I return to them for inspiration or direction.

So, what makes me bring up the self-help industry for writers? A progressive-minded document from 1952.

Browsing through the Eleanor Estes papers recently I came upon several drafts of her Newbery Medal speech, given in 1952 for her book Ginger Pye, which stopped me in my tracks. As I read the draft, complete with cross-outs and edits, I stopped at the excerpt at the top of this post and had to reread it. I copied it verbatim on my yellow legal pad. Estes, a former librarian in New York City, said this was not her first speech. She had given many of them, in her head, putting herself to sleep at night imagining that she had won the award. What she was saying could have easily been included in a how-to-write guide; it still could.

With so much written about the psychology of writing – directly or indirectly – the truth remains elusive. What works for some will not work for all. I know for a fact that I do not have the motivation to write at 4:30 a.m., as some writers do. My most productive work time is sometime between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. It used to be from 9 p.m. to midnight, before my kids entered the picture. I have had numerous ideas come to me while on bike rides and while driving my car, though I would hesitate to say there is a direct correlation between generating writing ideas and movement. Perhaps through doing these activities, my mind has an opportunity to clear out some space for creative thought. But who really knows.

Reading from superior examples in the genre you’re writing seems to help warm up the brain. Perhaps it’s nothing more than mere imitation. But is this scientifically based? I doubt it, or know if it can be. Still, Ted Kooser, the Pulitzer Prize winning poet who has been the U.S. Poet Laureate, in interviews says he has done this, as have many other writers. When I was a journalist at the Providence Journal, before a major assignment an editor once sent me a handful of front-page feature stories from the Wall Street Journal before I started to write one of my own. I did “channel” something from those stories, but I think I was too young to figure out how the articles she sent could help me.

Nevertheless, I guess the Estes comment surprised me because of the time period in which she wrote it, and also because it still makes so much sense today. How could it not help to imagine doing the very thing you want to do? Isn’t visualization/imagery the most primitive version of positive psychology? Estes was priming her brain to write great works, and her nightly fantasizing ritual ultimately gave her a tight focus and, quite likely, a motivation.

It worked for her. Could it work for others?

Sifting through boxes of manuscripts in the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, I suppose, can have a similar effect: to gain a psychological edge in the writing process. It’s easy to forget sometimes that writing is truly an art form, and that artists need inspiration and particular conditions in order to do it well. Whether it’s writing near the window at Starbucks, which seems to be a favorite for many, or in a secluded study room at a library, I’m not sure if there are any big secrets that will work for everyone. The trick, I think, is discovering what will work for you.