The following guest post is by Jerrold Connors, an award-winning application developer, writer and children’s book author and illustrator from California. He was recently awarded the James Marshall Fellowship to pursue a picture book project based on Harry Allard’s Miss Nelson stories. The James Marshall Fellowship encourages the use of unique materials in the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection and provides financial support to authors and illustrators for travel to University of Connecticut’s Archives and Special Collections to conduct their research.

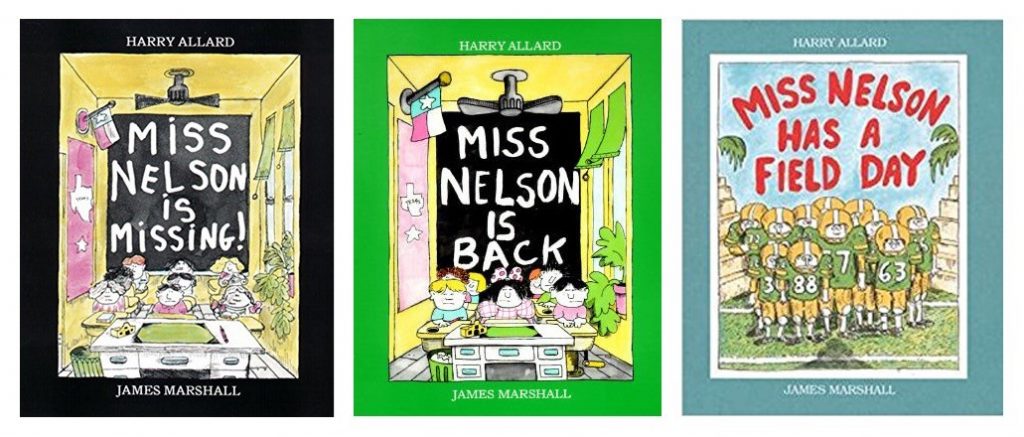

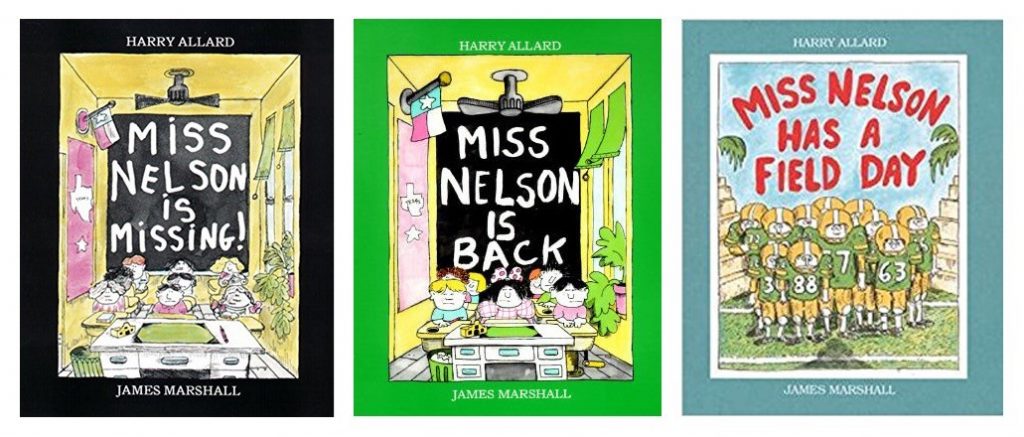

James Marshall, considered by Maurice Sendak to be one of the wittiest and most genuine children’s book author-illustrators, created the popular George and Martha stories, the charming Fox readers and the everlasting Miss Nelson picture books. He wrote and illustrated most of his stories himself, collaborated on several others with his friend and co-author Harry Allard, and illustrated the works of a few others. Marshall published upwards of 80 books from 1967 until 1992 when he died, aged 50, from AIDS. Though awarded few professional honors, Marshall is considered by many as one of the picture book greats—his works are held alongside those of Maurice Sendak and Arnold Lobel (with whom Marshall shared close friendships) as classics.

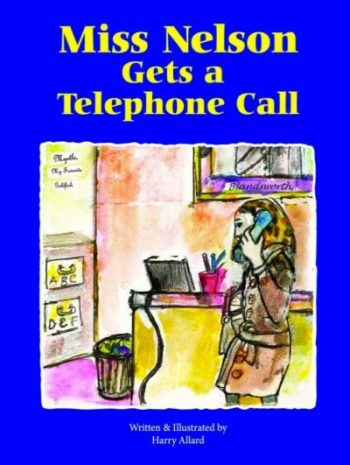

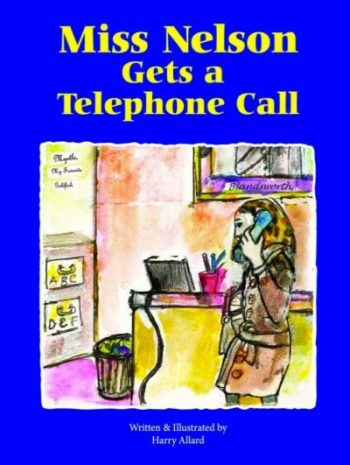

Miss Nelson Gets a Telephone Call (2014)

Despite growing up an avid reader in the early 1980s, I have no memories of reading any James Marshall books. It was only later, as a teenager reading to my nephew and niece, that I would discover the Miss Nelson books. And it was much later as a young adult reading picture books for my own enjoyment that I would discover George and Martha. I became a confirmed James Marshall fan and sought to find as many of his works as I could. I can think of very few creators whose entire body of work—unmistakable for its sense of fun, economy of language, subtle play between words and illustration and great respect for his young audience—I hold in higher regard.

Relatively little has been written about Marshall’s life and works but I have tracked down what I could and have come to consider myself something of a Marshall expert, so it was with great surprise and interest that I discovered a fourth Miss Nelson book, Miss Nelson Gets a Telephone Call, written, illustrated and self-published by Harry Allard in 2014, twenty two years after James Marshall’s death.

Miss Nelson Gets a Telephone Call is a peculiar work. It features all the Miss Nelson standards: a kind teacher, a befuddled principal, an elementary school setting, and a mystery surrounding a secret identity (the hallmark of the Miss Nelson series). But it also has an enormous cast of characters, a generous amount of exposition, a bizarre wordiness (gothic adjectives such as graustarkian, eldritch and stygian abound) and a distinctly creepy tone. And it is missing, notably, any children.

All these facts made me wonder how similar Miss Nelson Gets a Telephone Call is (if at all) to the original Miss Nelson trilogy. It’s a known fact that James Marshall heavily edited the authors’ texts that passed his drawing table (an unusual practice for an illustrator) but I wanted to know just how far Marshall went in shaping Allard’s manuscripts into the illustrated stories we have come to know. The books credited to Marshall and Allard are nearly identical in voice, pacing and humor to those credited solely to Marshall. So much so that it has even been suggested that Harry Allard might have been an invention, like Marshall’s “cousin” Edward Marshall, to serve as a pseudonym. While this would be wholly appropriate given the Miss Nelson tradition of dual-identity and disguise, it is not true. Harry Allard was a real person.

The two became acquainted at Trinity College in San Antonio, Texas where Allard taught French and Marshall was an undergraduate. An academic, Allard held a Masters degree and PhD in French from Northwestern and Yale. He was an admirer of French illustrators and drew and sketched as a hobby and in this sense found a kindred spirit in the artistically minded Marshall. They collaborated on a few picture books with Allard credited as author and James Marshall as illustrator before developing the character of Miss Nelson. As the story goes, Allard called Marshall at three in the morning and said “Miss Nelson is missing!” This bizarre non sequitur became the seed that would grow into three books about the teacher and her class.

The Northeast Children’s Literature Collection holds a rich and rewarding amount of materials related to the working relationship between James Marshall and Harry Allard. Of those materials related to the Miss Nelson book, the most complete were those for the second Miss Nelson book Marshall and Allard worked on together, Miss Nelson Is Back.

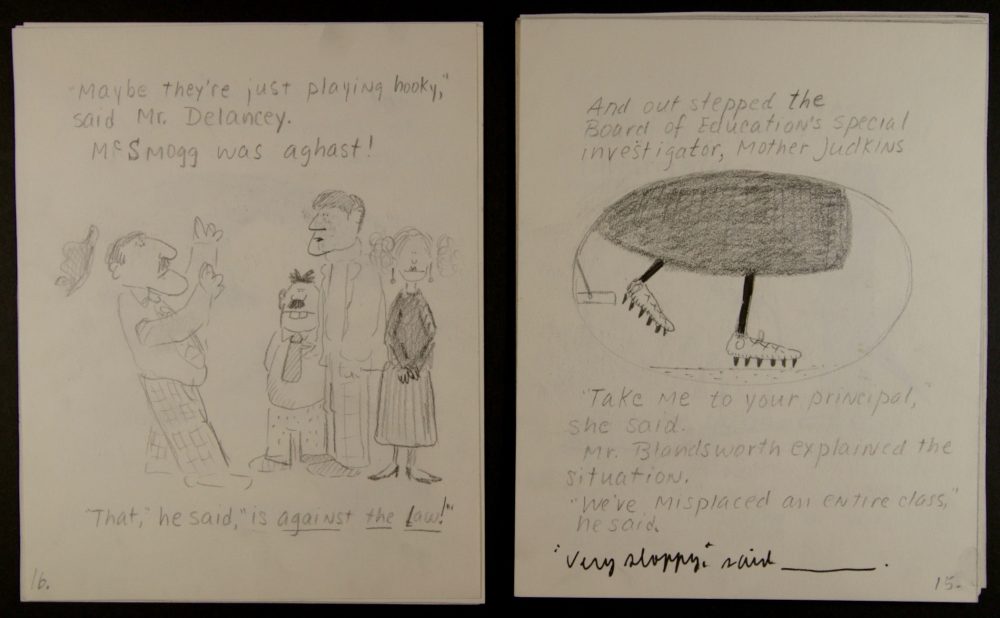

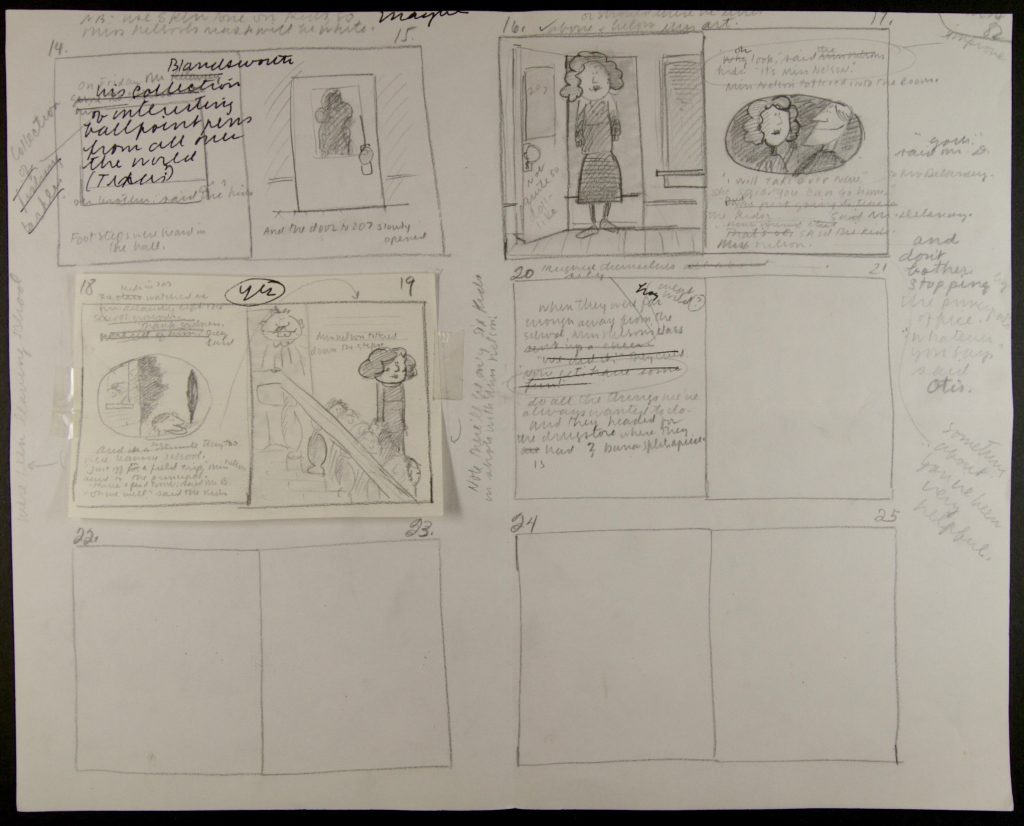

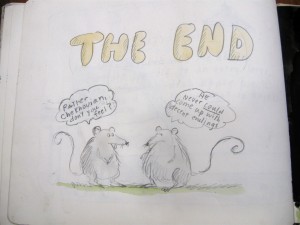

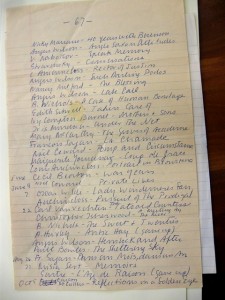

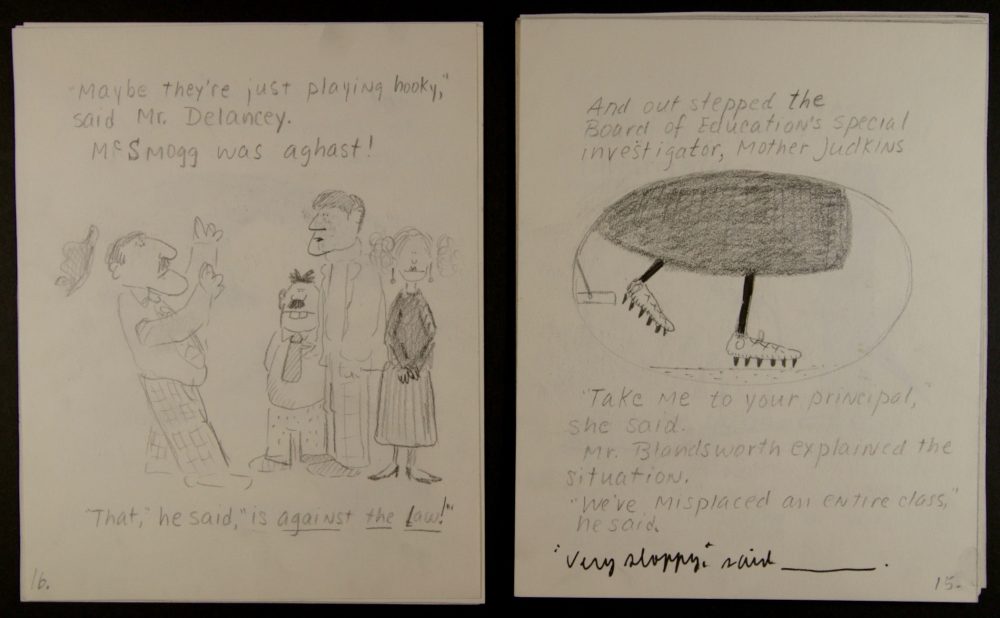

Miss Nelson Is Back: In the collection in Archives and Special Collections at the University of Connecticut is a series of dummies for Miss Nelson Is Back. The earliest of these dummies hints at what must have been Harry Allard’s original manuscript for this story. The story opens with Miss Nelson having to leave her class for a tonsillectomy. Filling in for her is a new character, Mr. Otis Delancey, a well-intentioned if inexperienced substitute teacher. The kids of Room 207 are more than ready to take advantage of him. Rounding out the cast is Miss Gomez, the school’s secretary, Detective McSmogg (a private investigator from the first Miss Nelson book, this time acting as a truant officer), and Mother Judkins, “special investigator” for the Board of Education.

Dummy for Miss Nelson Is Back

With all these characters, the strictest substitute teacher in the world, Viola Swamp (the true star of the Miss Nelson books), gets very little screen time; in fact, her appearance is gratuitous. There is none of the guessing and second-guessing of double identities that made the first Miss Nelson book so much fun.

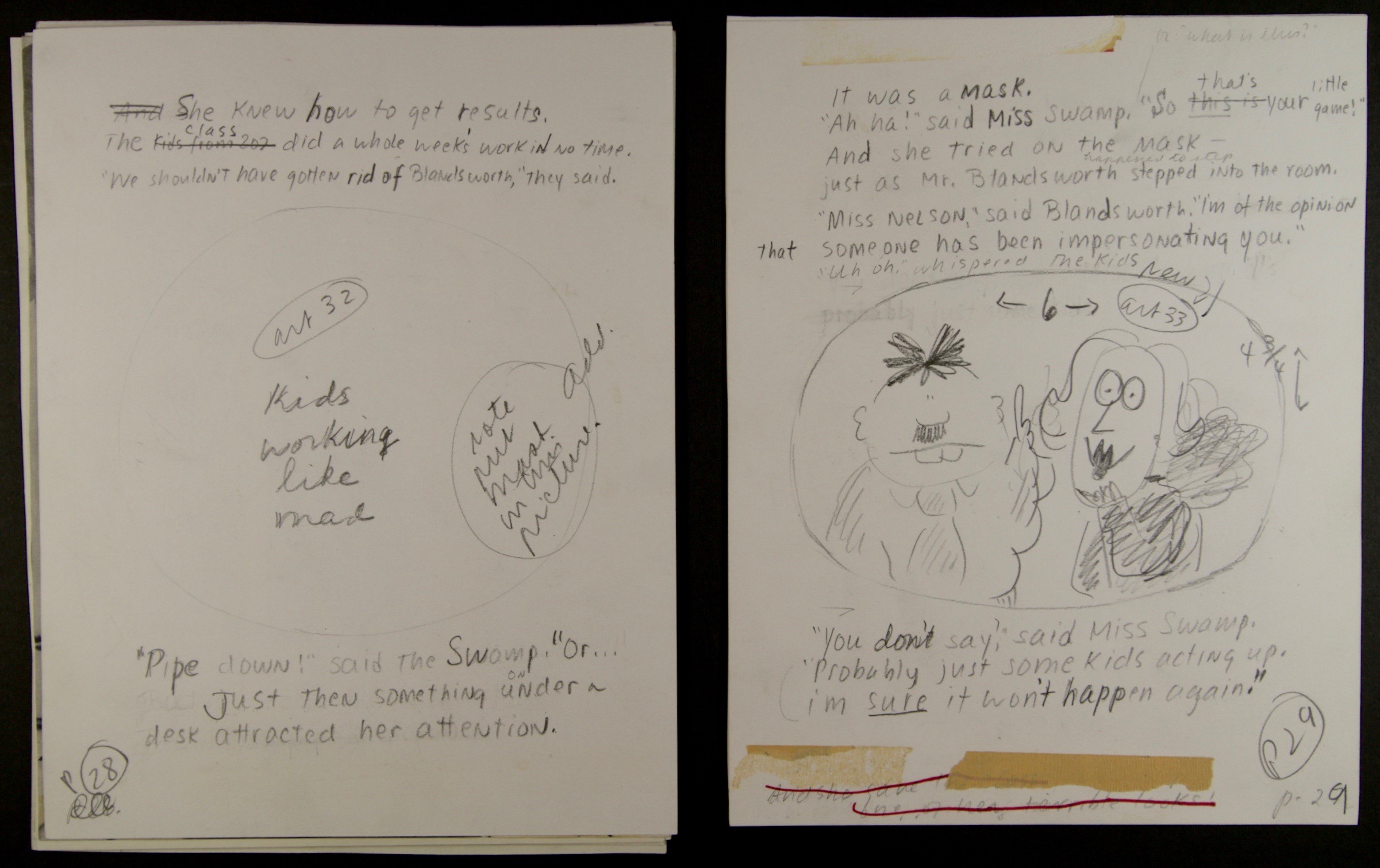

Looking through the collection of dummies and storyboards, I saw that within two drafts Marshall had put Harry Allard’s story through its paces, trimming the number of characters to a splendid few, namely, Principal Blandsworth, Miss Nelson, Viola Swamp and, of course, the kids of Room 207. The greatest fun in the story—the kids impersonating Miss Nelson in a terribly obvious and obviously terrible disguise—had been fully fleshed out and the text had been trimmed to nearly what would appear in the final printed version.

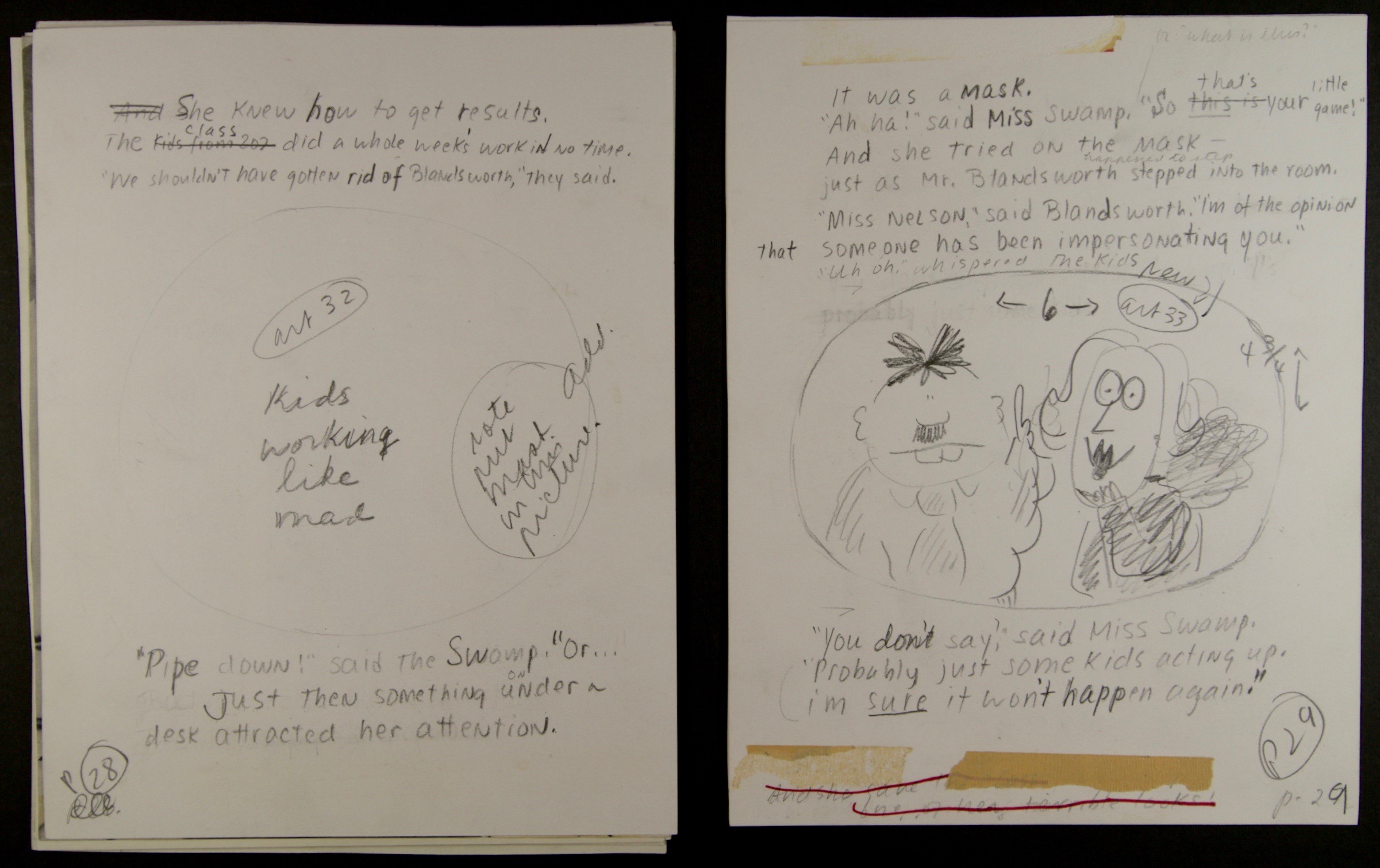

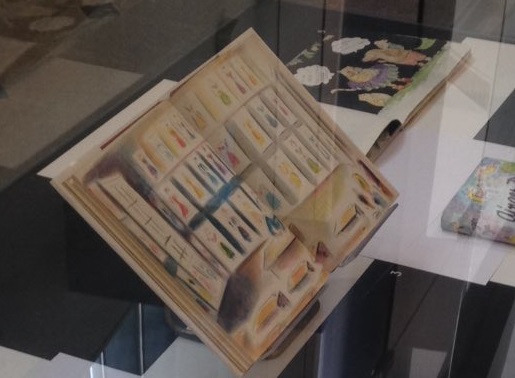

Book dummy for Miss Nelson Is Back

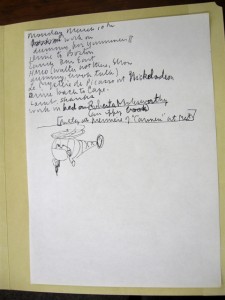

The edits on these dummies are all executed in Marshall’s distinct handwriting. Entire sections have been cut, others invented on the fly, hastily scribbled in between and alongside blocks of discarded text. Editing happens not just of Allard’s work but also of Marshall’s own. Marshall writes several versions of the line “So this is your little game?”, trying “What is this?” and settling on “So that’s your little game!” (In method it is very similar to a book done entirely by Marshall alone, The Cut Ups Carry On, which also exists in the archives and is splendidly detailed by Sandra Horning in her blog entry here.

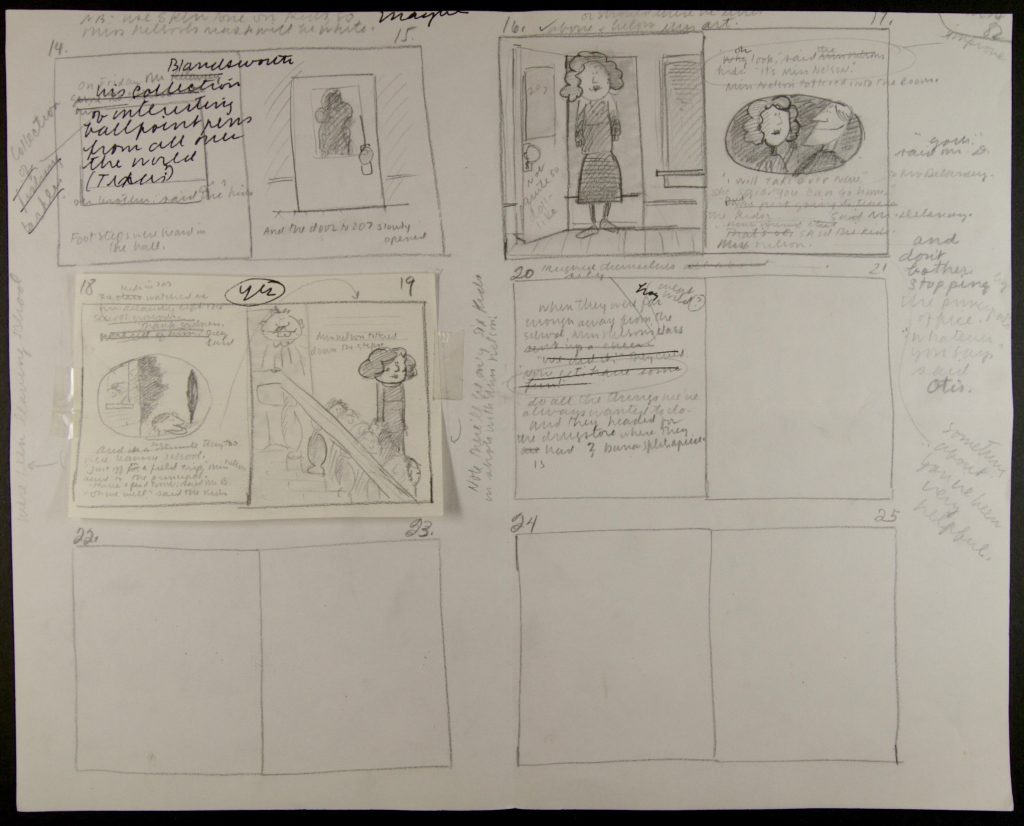

Tracking changes through these drafts, it is very clear that what would appear as the final version of Miss Nelson Is Back was very much a Marshall story. For his part, Allard must have been okay with Marshall’s reworking of his script. Miss Nelson Is Back was their ninth book together, their second Miss Nelson book and they would go on to do another. I noticed also that Marshall sought to preserve some of Allard’s inventions through his drafts. Otis Delancey survived the transition from first draft to a storyboard before he was cut.

Last appearance of Mr. Otis Delancey, Storyboard, Miss Nelson Is Back

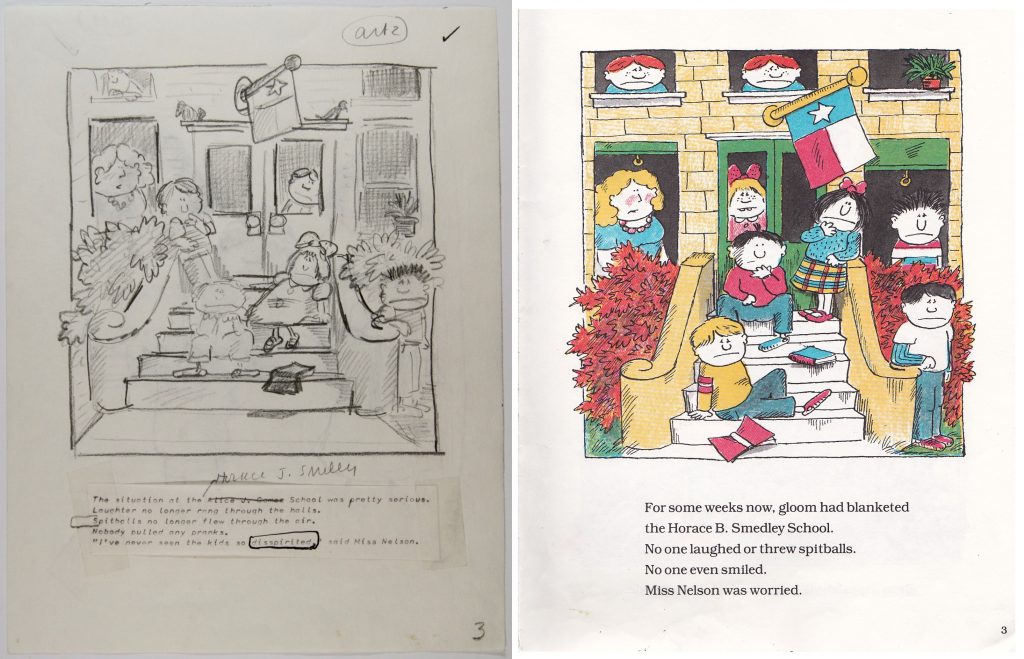

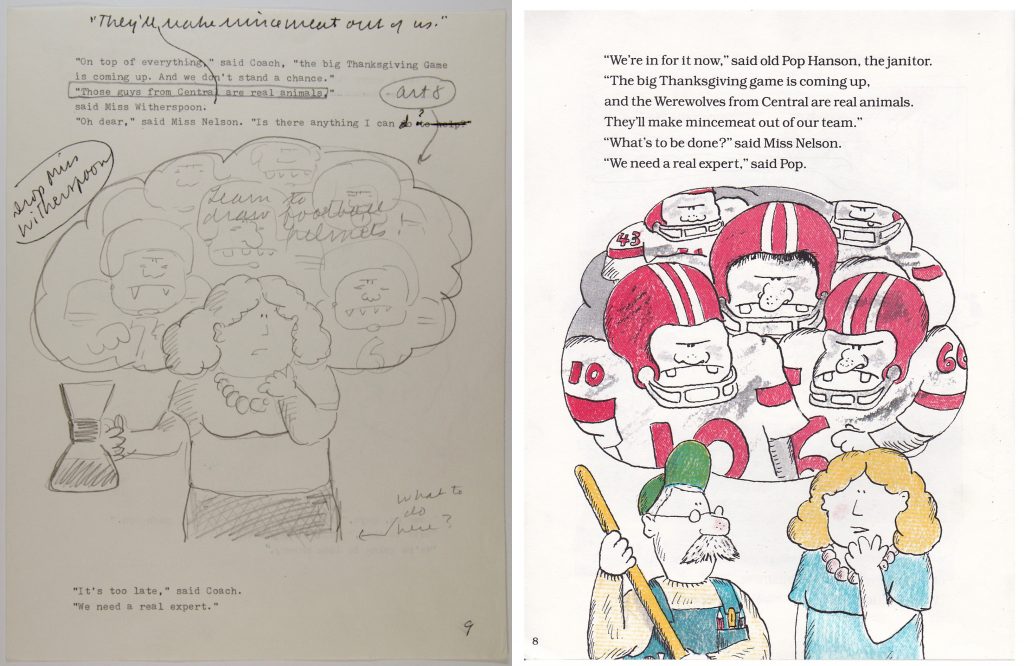

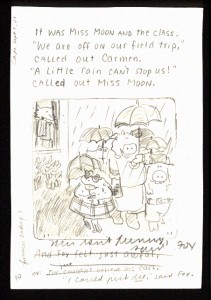

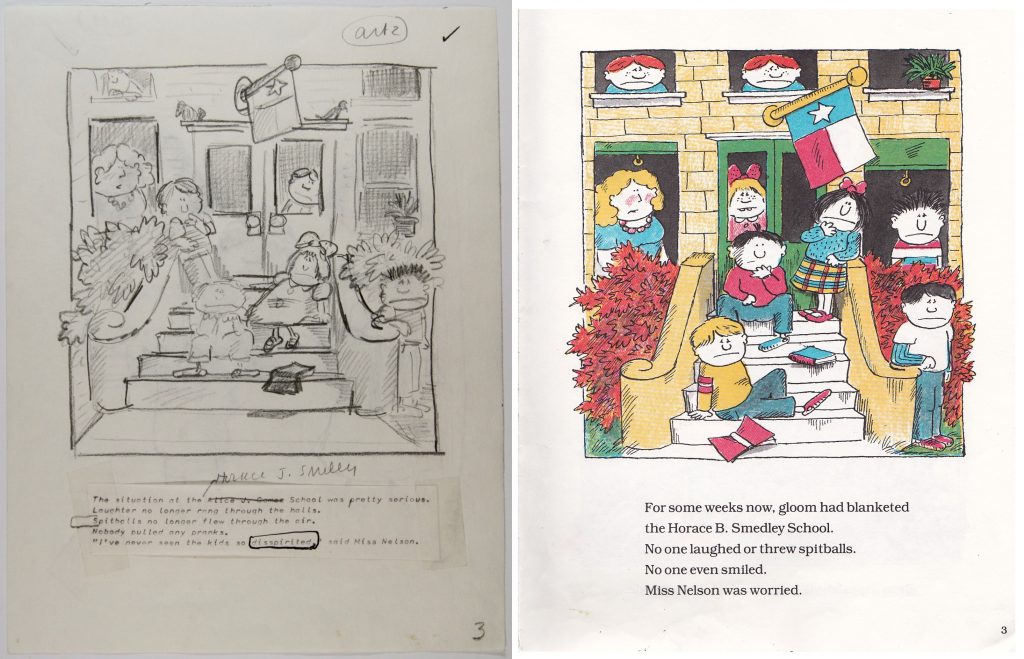

Miss Nelson Has a Field Day: The first pages of the dummy for Miss Nelson Has a Field Day* (Marshall and Allard’s third Miss Nelson book) is a combination of pencil illustrations with pasted down clippings from a typewritten manuscript. Whether or not the manuscript came directly, unedited, from Allard is unknown, but some clues indicate that it did. For one, the school in this story is named “Alice J. Gomez Elementary.” According to Marshall’s partner William Gray, Allard could become fixated on certain details such as odd words or funny names—that he would bring Miss Gomez back to the Miss Nelson universe seems in keeping with this habit. And, as in Miss Nelson Is Back, Allard has attempted to enlarge the faculty, this time with Miss Witherspoon, the cheer squad coach.

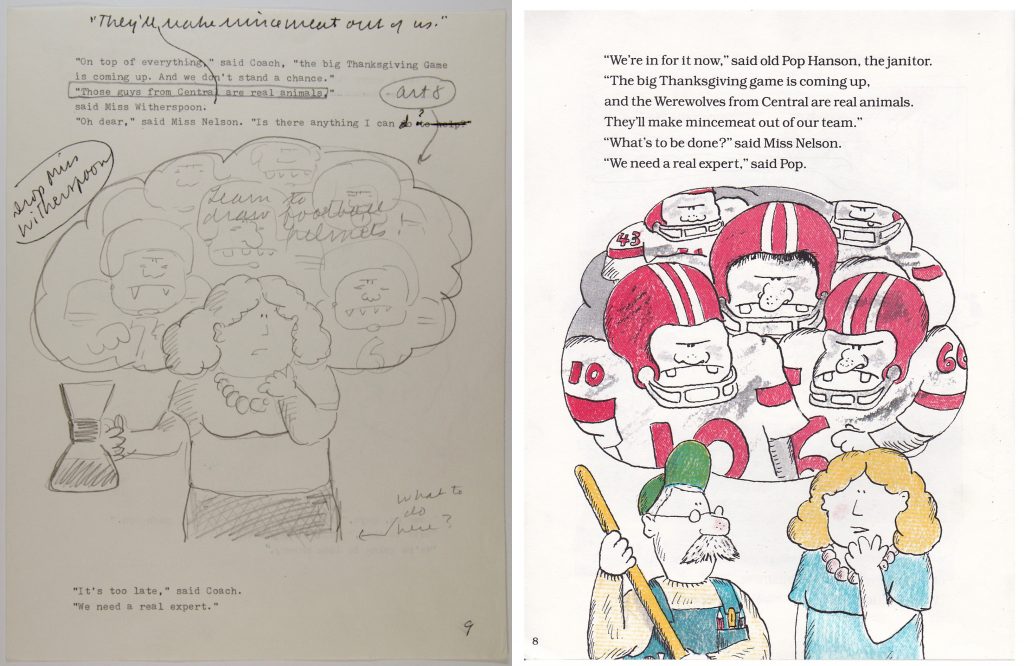

Dummy and final print comparison, Miss Nelson Has a Field Day

Dummy and final print comparison, Miss Nelson Has a Field Day

Eight pages into this dummy Marshall begins composing the pages by typing directly onto his drawing paper. A few pages beyond that and Marshall begins writing in his distinct hand, using shorthand to get his ideas quickly onto the paper as they occur to him. As with Miss Nelson Is Back, Marshall appears to be inventing on the fly, using this stage of his process to both trim and flesh out the story and ultimately make it his own.

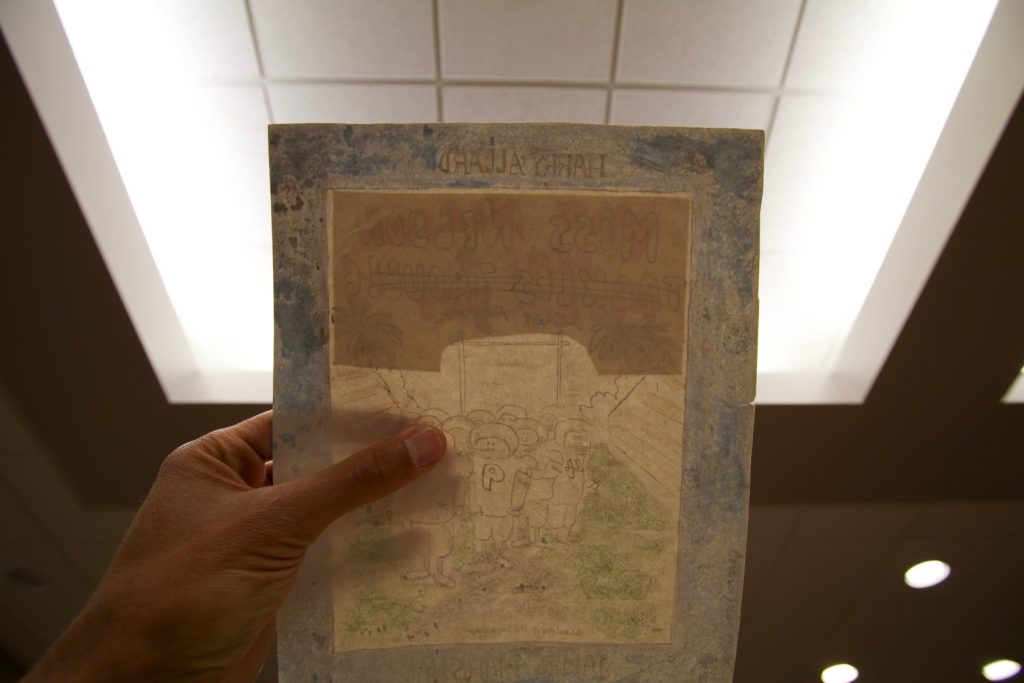

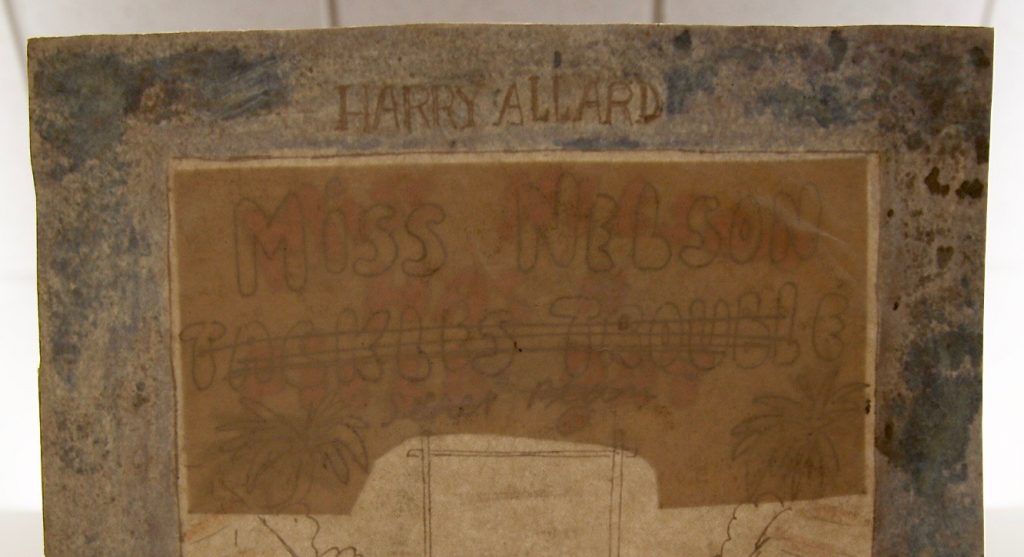

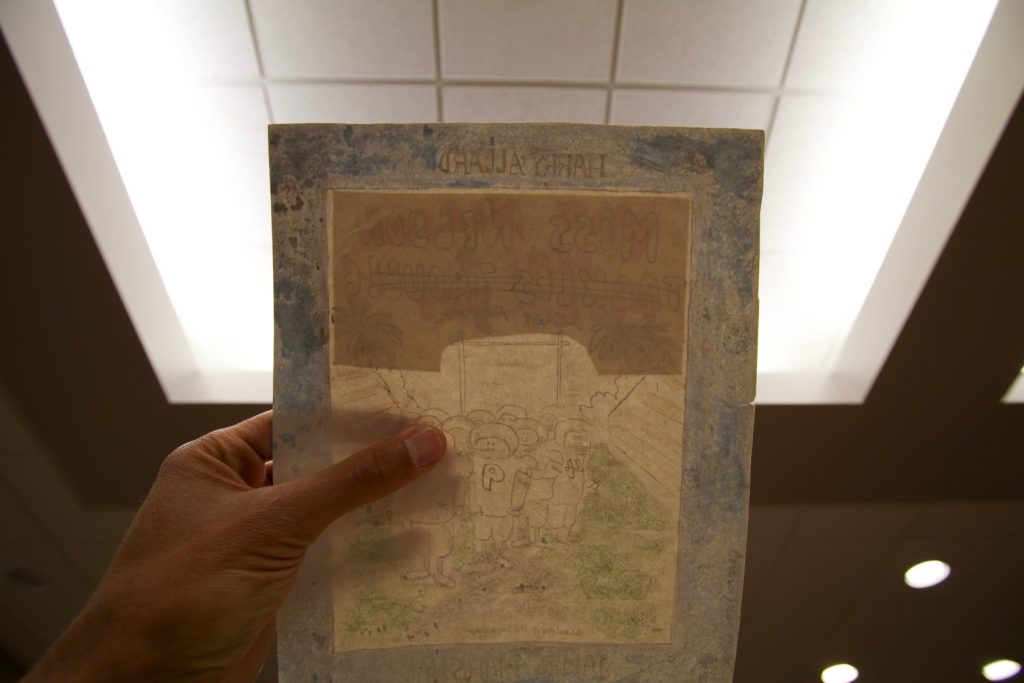

*footnote: Holding the original cover concept for Miss Nelson Has a Field Day up to the light revealed that the working titles to this story were at one point Miss Nelson Tackles Trouble and Miss Nelson’s Secret Play.

Cover concept sketch, Miss Nelson Has a Field Day

Cover concept sketch closeup, flipped, Miss Nelson Has a Field Day

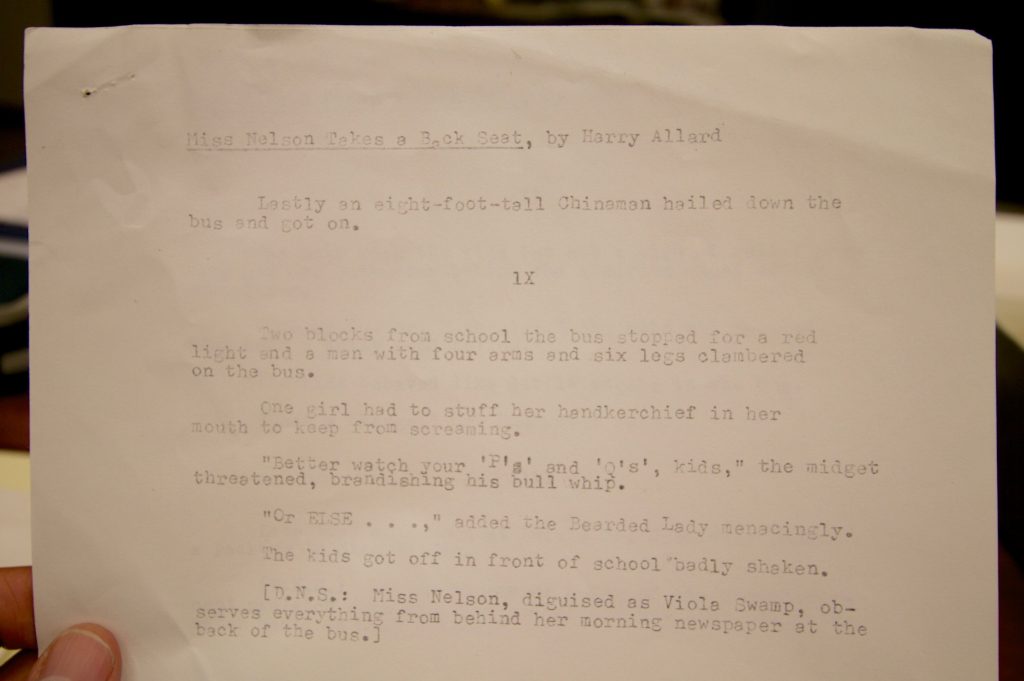

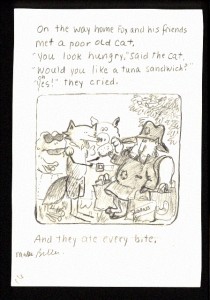

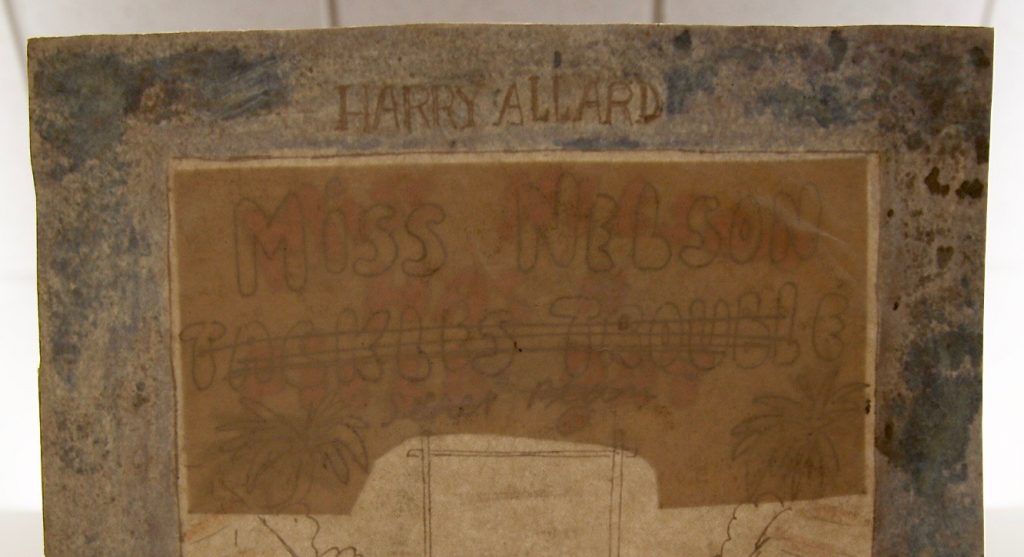

Miss Nelson Takes a Back Seat: The collection also held a three page typewritten manuscript by Allard for an unpublished story titled Miss Nelson Takes a Back Seat. Dated 1989, this story expands Horace B. Smedley Elementary’s world to include a school bus service, an appropriate enough story device, but there is little else in the way of character or plot. The entire story is mainly a vehicle for some gags about members of a circus sideshow.

“Better watch your ‘P’s’ and ‘Q’s’’ , kids,” the midget threatened, brandishing his bull whip.”

Typewritten draft by Harry Allard, Miss Nelson Takes a Back Seat

There are no marks by Marshall on this document, and no evidence I could find in the abundant collection of sketchbooks (used often for brainstorming and testing story ideas) that he ran with the idea. Whether this was because Marshall at this point in his career was focusing on retelling fairytales or because he felt the Miss Nelson adventures had been played out is unknown. Although not a trilogy in a strict storytelling sense, the three Miss Nelson books form a tidy whole. Miss Nelson Takes a Back Seat doesn’t add anything to the Miss Nelson world.

Miss Nelson Is Missing!: From the previous examples, it is obvious that the majority of work that shaped the Miss Nelson books into what the public has come to know was executed by Marshall. This isn’t to say that Marshall didn’t value Allard’s contribution. Allard was a brainstorming partner, a writer who could turn out pages of script allowing Marshall to indulge in editing, evidenced many times in the collection as one of Marshall’s great strengths.

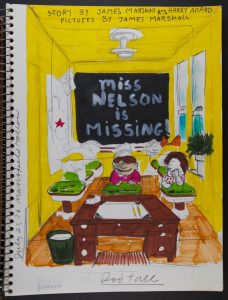

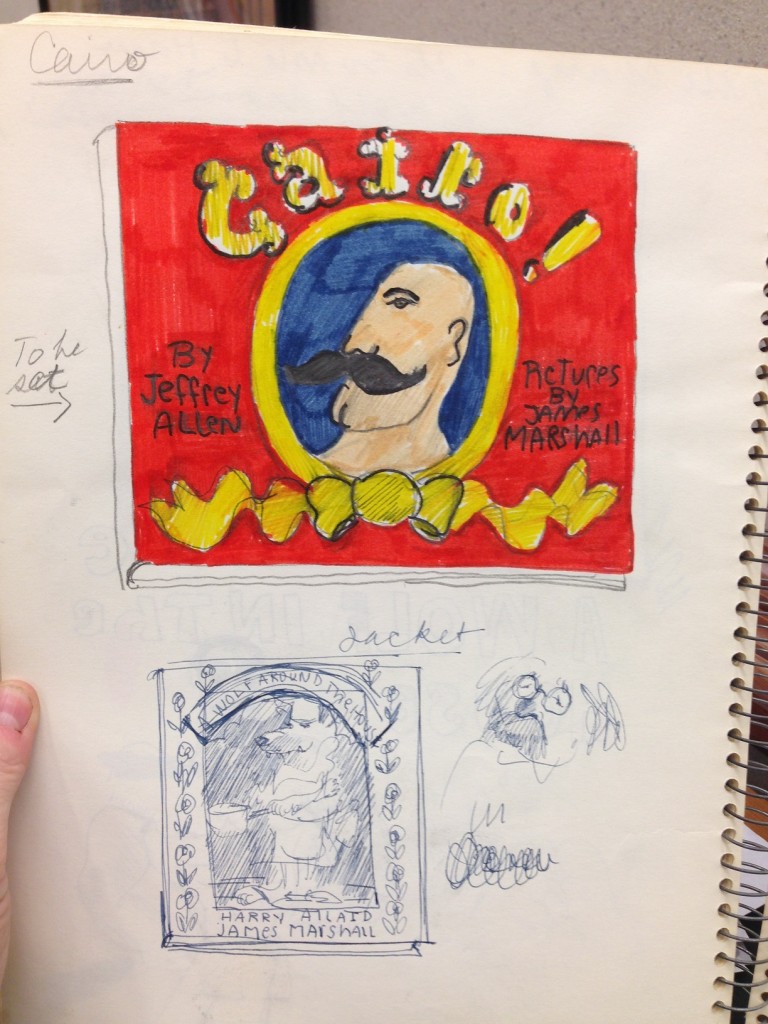

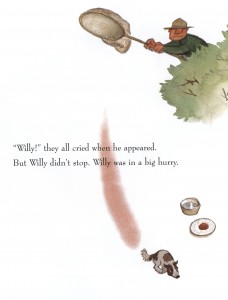

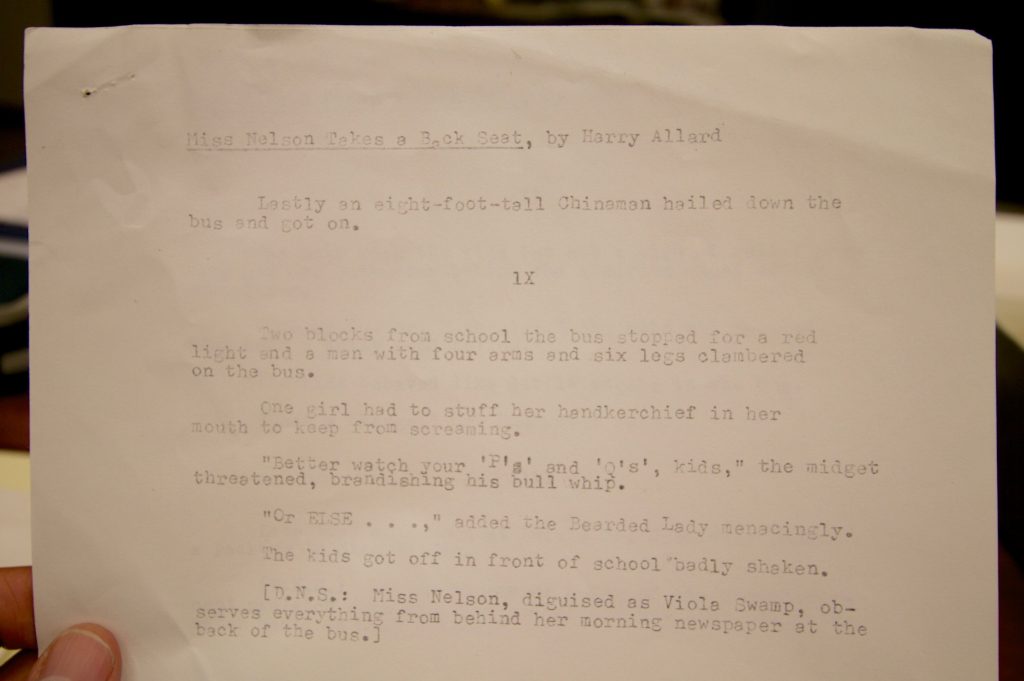

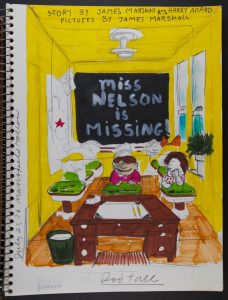

Cover concept sketch, Miss Nelson Is Missing!

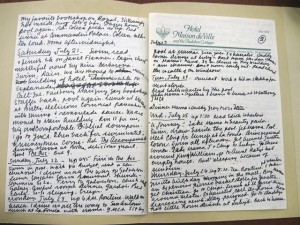

Late in my research I discovered a single page near the back of one of James Marshall’s sketchbooks. This book, sitting nondescriptly in the middle of Box 20, held a cover concept sketch for Miss Nelson Is Missing! Dated July 27, 1976, the sketch would have been made about one year before the first Miss Nelson book was to be published. At the top of the page Marshall had written “Written by James Marshall and Harry Allard”.

He then drew a double headed arrow to transpose his and Allard’s name to give Allard top billing. Eventually the cover page would remove the “written by” and “illustrated by” lines and feature the two names as collaborators with Allard’s name featured generously at the top of the page.

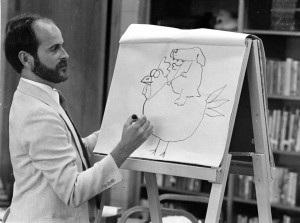

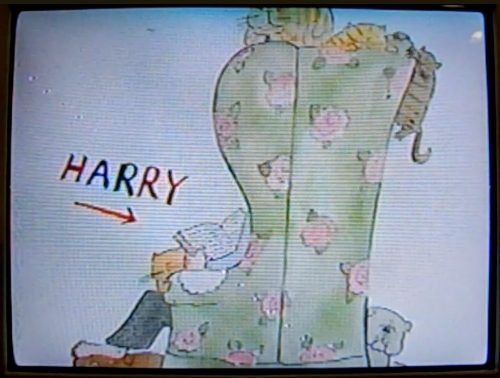

But despite the vast source of materials related to the Marshall/Allard collaborations, it was a very small thing that most informed my understanding of their relationship. In the seventeen minute James Marshall In His Studio video (one in a series produced by Weston Woods/Scholastic to introduce authors to their audience) Marshall speaks directly to the camera, explaining his process in creating picture books. In talking about where his ideas come from, Marshall describes the infamous 3am phone call from Allard. I’ve alway read the line “Miss Nelson is missing!” as an exuberant, even manic, exclamation on Allard’s part. But as Marshall tells the story (at the nine and half minute mark if you should ever be so lucky to find a copy of this recording) it is far more nuanced. Marshall does an impression of Allard’s voice. It is theatrical, a little affected, mysterious. It’s done with a smile and, clearly, affection for his friend.

Marshall appreciated in Allard all those things I found peculiar. His eccentricities delighted Marshall. What’s more, Allard’s inspirations—whether they ultimately served to chart the inappropriate, or uncover the promising—informed Marshall’s talents. Given the amount of work Marshall put into their collaboration, that he would give his friend top billing is testimony to Marshall’s generosity. But it would be shortsighted to consider it charity. Marshall truly valued his partnership with Allard. Like Miss Nelson and Viola Swamp, in this story one could not have existed without the other. If Harry Allard were missing, so too would be missing these three books.

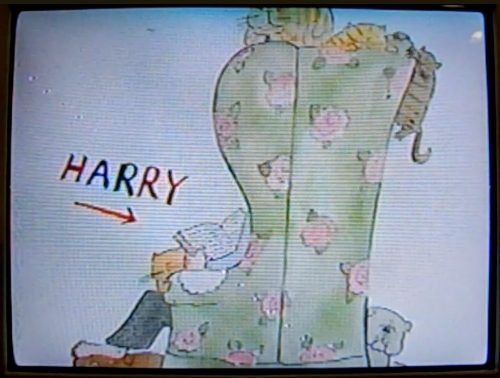

Still image from video, James Marshall In His Studio

The following is an excerpt of an exhibition essay by Nicolas Ochart, Student Exhibitions Intern in Archives and Special Collections, for an exhibition currently on view in the McDonald Reading Room in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. This semester, Nicolas is responsible for conceiving and developing small-scale exhibitions that highlight archival material found in the collections. He hopes to pursue professional curatorial work in an effort to promote the work and experiences of marginalized and underrepresented communities in the United States. In December, Nicolas will receive his B.A. in Art History from the University of Connecticut.

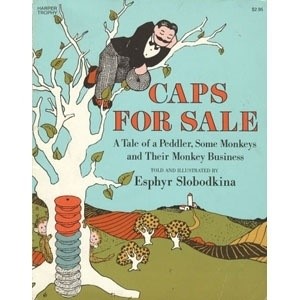

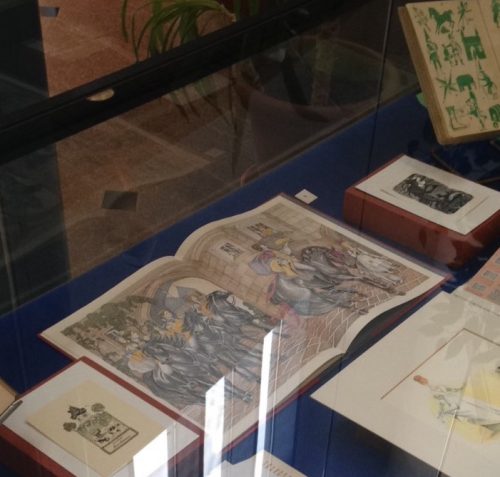

The following is an excerpt of an exhibition essay by Nicolas Ochart, Student Exhibitions Intern in Archives and Special Collections, for an exhibition currently on view in the McDonald Reading Room in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. This semester, Nicolas is responsible for conceiving and developing small-scale exhibitions that highlight archival material found in the collections. He hopes to pursue professional curatorial work in an effort to promote the work and experiences of marginalized and underrepresented communities in the United States. In December, Nicolas will receive his B.A. in Art History from the University of Connecticut. The collection’s extensive holdings have made the University of Connecticut a nexus for scholars and children’s book writers and illustrators across the nation interested in studying the literary and aesthetic qualities of the form. In an effort to support and encourage study of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, Archives and Special Collections have developed a number of awards for researchers, including the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant and the James Marshall Fellowship. Grantees and Fellows have written on such varied topics as queer American Jewishness in the art and writings of Maurice Sendak, as well as influences of modernism and fashion design in the work of Esphyr Slobodkina. Aspiring and established authors and illustrators have also looked at papers by James Marshall, Natalie Babbitt, Tomie dePaola, and Eleanor Estes for guidance in their own practice.

The collection’s extensive holdings have made the University of Connecticut a nexus for scholars and children’s book writers and illustrators across the nation interested in studying the literary and aesthetic qualities of the form. In an effort to support and encourage study of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, Archives and Special Collections have developed a number of awards for researchers, including the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant and the James Marshall Fellowship. Grantees and Fellows have written on such varied topics as queer American Jewishness in the art and writings of Maurice Sendak, as well as influences of modernism and fashion design in the work of Esphyr Slobodkina. Aspiring and established authors and illustrators have also looked at papers by James Marshall, Natalie Babbitt, Tomie dePaola, and Eleanor Estes for guidance in their own practice.