In February of 1845, Sherwood B. Ransom of East Haddam, CT visited the Island of Otaheite (Tahiti) in the Northern Pacific Ocean for his second time in two years. At the time, Ransom was sailing as a crew member aboard the Morrison, a whaling ship bound from New London, CT on what would become a lengthy cruise for whales through the Indian and Northern Pacific Oceans.

At Otaheite, Ransom was greeted by a pleasant surprise: here, he reunited with “Henry and Lyman,” two friends from home. Henry, probably Henry C. Griffens of East Haddam, had sailed with Ransom on a previous whaling voyage in 1842 aboard the New London ship Indian Chief, when Ransom made his first visit to Otaheite. “Lyman” (William Lyman Cole of East Haddam) was a “green hand,” or first time whaler. Ransom writes the following about his encounter with his friends:

got into the harbour about Eight[.] found three New London Ships there the India, Jefferson, and Neptune[.] went aboard of the Nep. Saw Henry and Lyman, found them well…came aboard about dark and started for the Sandwich Islands…Lyman likes whaling first rate[.] we had a first rate visit[.] I took dinner with them, and shall see them at the S. [Sandwich] Islands again.

This run-in with friends, though rare, but not unlikely, with so many New London ships at sea following similar voyage paths in the 1840s.

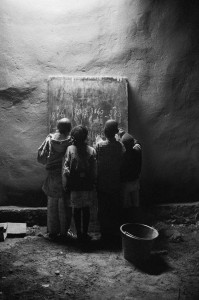

Opening page of Sherwood Ransom’s journal. The whale stamps at the top were typically used in whaling logbooks to provide a visual record of the number and type of whales caught.

I was over the moon when I saw that the diary collection in Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center included a whaling diary from a New London ship. In my other life as a student, I am researching the history of New London-based whaling in the southern Indian Ocean for my University Scholar project. During the nineteenth century, New London, CT became the second largest whaling port in the nation (New Bedford was the largest), employing men to sail throughout the Atlantic, and later the Pacific and Indian oceans in search of whales to kill for their blubber. When boiled, the blubber became oil that was used for lighting and as an industrial lubricant.

The Morrison’s journey lasted a total of four years (September 1844 – May 1848), but the majority of Ransom’s diary is composed of daily entries from 1844 and 1845, with a few entries penned in 1847. Ransom served as a boatsteerer on this voyage, a “promotion” from his previous work on the Indian Chief. Though not quite an officer, boatsteerers commanded authority on whaleships, different from regular crewmen in that they were hired for their specialized ability to harpoon whales and to steer the small “whaleboats” deployed from the main ship from which the whalemen hunted whales.

For Ransom, writing in a journal seems to have been both a refuge from the claustrophobic realities of whaling life as well as a way to pass the time. The majority of working time during a whaling voyage was spent performing mundane, shipboard duties or boiling blubber on a ship’s “tryworks” until a lookout sighted whales to hunt. In between, there was plenty of time to write. That being said, with the routine of the ship always contingent on the whims of nature (the availability of whales or changing wind patterns that made it necessary to adjust the sails) leisure time could easily transform into work time.

The lack of distinction between work and leisure is clearly evident in Ransom’s journal, with daily entries including both personal details and descriptions of routine shipboard work. “No[t] all hands to day and not much doing except two hours scrubbing decks and two spells setting up some of the head gear” he writes on September 22 (1844). “[H]ave had a good wash and shave and feel much revived after the operation. Stiff breeze as yesterday.” A report on the direction and strength of the wind is included in each of Ransom’s entries.

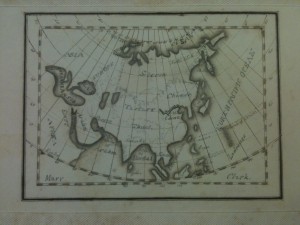

Ransom also scribbles details about latitude and longitude, as well as any whales captured on a given day in the margins of his journal. These details, normally committed to official ship’s logbooks, suggest that Ransom was understandably doing a bit of unofficial record-keeping himself. With the ship being both his workplace and his home, details that were important to the ship’s work became important to him; they determined his routine, his fatigue, and his happiness on any given day.

The regular timing of Ransom’s journaling suggests that writing became part of his shipboard routine, but was uniquely one of the only activities that afforded him a sense of privacy and security. The sense of refuge gained from writing in his journal is indicated by Ransom’s use of the diary to disclose intimate concerns. His entry from New Year’s Day 1845 reveals his feelings about missing home and family:

This is the first day of the year[.] how I wish I was at home to enjoy it by meeting in the social circle of young friends and to greet them a Happy New Year. But fate was so ordered that this poor devil is to be here in the ship Morrison many thousand miles from home and friends[,] though not friendless I hope and if my life is spared will be here twelve months from this. I have thought of home much to day, and of the past summer which I spent in East Haddam and how differently I am situated from what I was then.

However, the refuge provided by writing was only temporary; the intrusion of life at sea is continuously present. A page, smeared with ink includes the following note: “While I have been writing the foolish old ship gave a lee lurch and capsized. My ink on my book and has made a pretty spot so I think I will below and wait for better weather.”

As the voyage progressed, Ransom used his diary to voice frustrations about the officers on board, notably Captain Samuel Green. He writes the following after Green scolds him for an unsuccessful whale hunt:

Friday 25th [May 1845]: …I darted at him [the whale] but did not get fast and off he went as if the Devil was after him[.] came aboard and the old man [Capt. Green] was savage Enough but who cares for his lip[?] I do not[.] if he does not like my boat steering he can get some one else and I shall tell him so if he says anything more on the subject.

It is likely that writing these frustrations in a diary was the only way that Ransom could safely voice them without running the risk of being overheard, which would have resulted in him “catching it,” or being punished, by one of the officers.

At one point in 1845, Ransom, fed up with his captain, work, abysmal living conditions, and the inexperienced “fools” who were his fellow crewmen, threatens to abandon the operation altogether: “..[I]f ever I get into a good port,” writes Ransom, “I shall ask him [Captain Green] for my charge and if he does not give it to me he must keep a good lookout for me[.] he is a drascal as has ever lived these are my feelings at the present.”

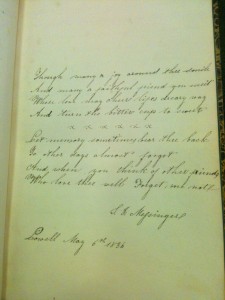

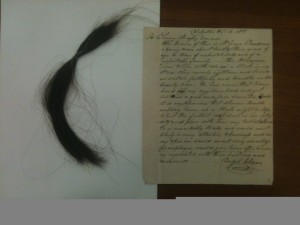

The lock of hair and letter of reference for George Ransom included in the back of Sherwood Ransom’s whaling journal.

Whether or not Ransom ever did abandon the voyage is unclear – his journal ends abruptly in 1847.

Though his quick promotion to a boatsteerer indicates he was a competent whaler, it seems clear that Ransom was more interested in returning to East Haddam to work and live. Close ties to home are suggested by his New Year’s lamentations and his excitement over seeing Henry and Lyman at Otaheite, but they are also a physical feature of his journal. Tucked in the back pages are military papers and a letter of reference written for his father, George Ransom, as well as a lock of hair, likely belonging to a deceased family member.

Though these were likely added by Sherwood or another family member upon his return, their presence in the journal is tantalizing and indicative of a larger trend – most whalemen did not stay in the whaling industry for all of their lives. Many worked as whalemen for only a few voyages before earning enough money to return home and start a family; it appears Sherwood did this, marrying Abbie Payne, a woman from Colchester, CT in 1851, and living out the rest of his life on land until his death in 1893.

Rebecca D’Angelo is a senior undergraduate student in History and Anthropology. In her blog series For Private Eyes Only she studies diaries available in Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center and explores the history of journal writing and reasons why we write journals.