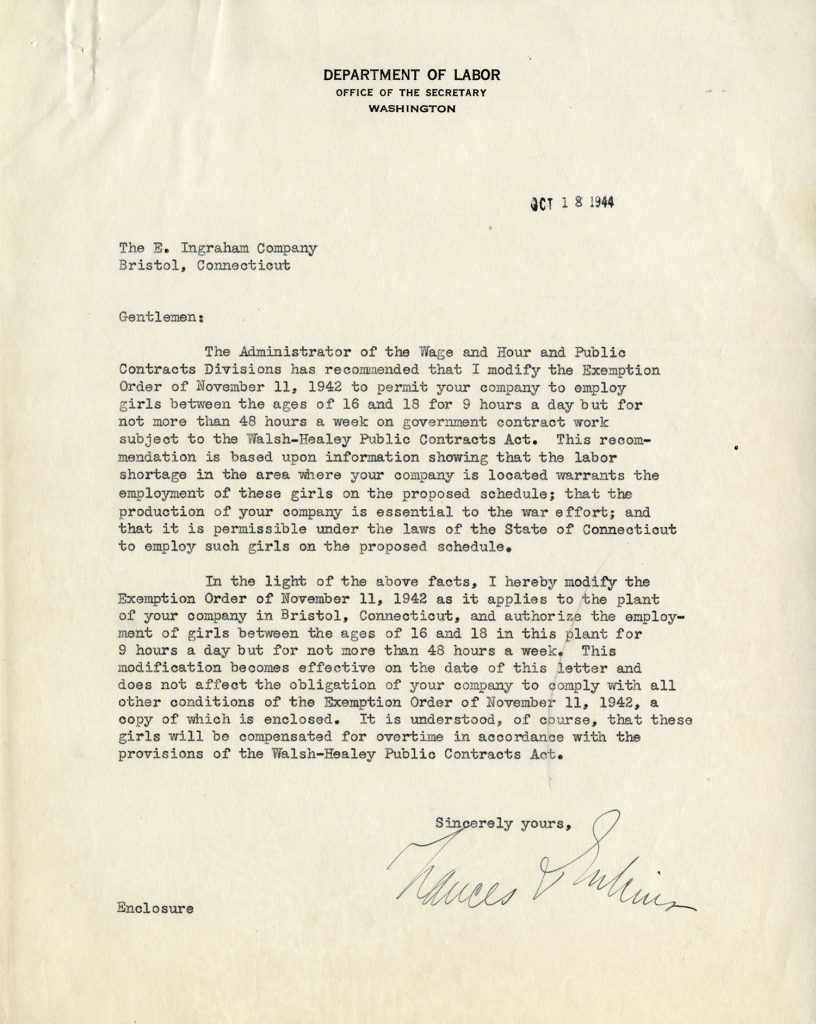

This post was written by Shaine Scarminach, a UConn History Ph.D candidate who is a student assistant in Archives & Special Collections.

Walking around the Storrs campus, you might notice the name “Whitney” in places. It rests on a street sign here; sits in stone above an entrance there.

But who is this Whitney? And how do they fit into the University of Connecticut’s long history?

The Whitney family made a lasting impression on the University of Connecticut, though that impression has faded with time.

Edwin Whitney, a local school teacher, built the first building and provided the first land for the school when it was founded in 1881 as Storrs Agricultural College.

Edwin completed the structure in 1864 with the plan to open a private school for boys. But he offered it to the state a year later as a home for Civil War orphans. It served this purpose until 1875 when all the children had aged out of the program.

The building and its fifty-acres of land were then sold in 1878 to Charles and Augustus Storrs, who handed the parcel back to the state a few years later to help found the institution that became the University of Connecticut.

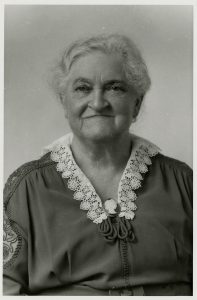

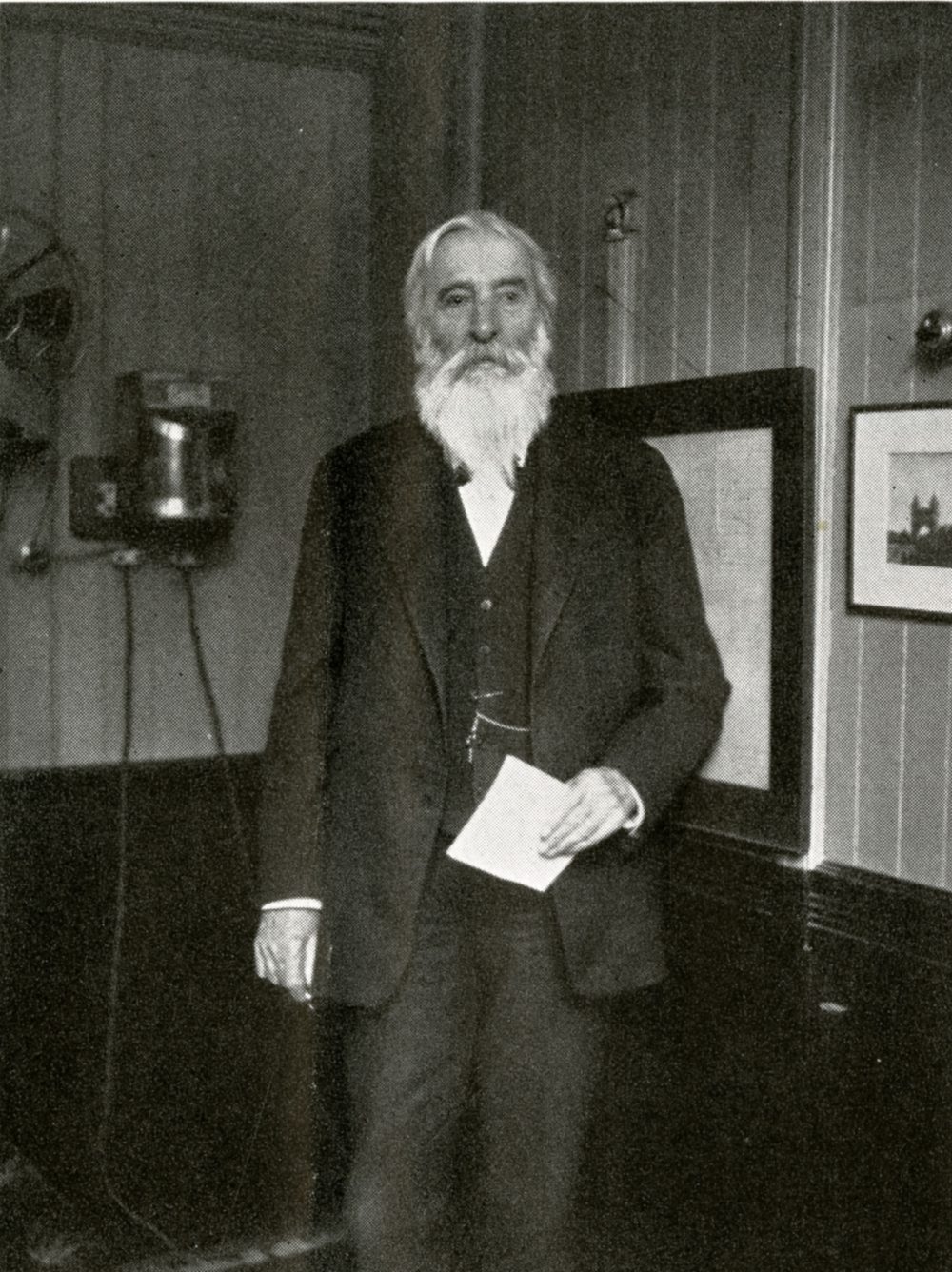

Edwina Whitney, named after her father who died shortly before she was born on February 26, 1868, also played an important role in the early history of the school.

Edwina grew up in Storrs and spent most of her life there. Her mother even operated the post office out of their home for a time.

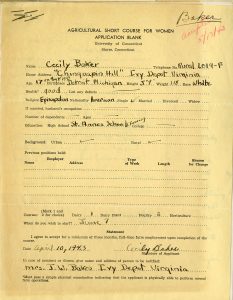

Edwina left Storrs to attend Oberlin College in Ohio, graduating in 1894. She then taught for a year in Wisconsin before returning to Connecticut. After completing a summer library science course at Amherst College, she took the position as College Librarian in 1900. She would hold it for the next thirty-four years.

Edwina’s career as college librarian began in spartan circumstances. The library at what was then known as the Connecticut Agricultural College was kept to two rooms in the main building, lighted only by dim kerosene lamps.

Over the years, library accommodations (as well as her salary) improved, though student behavior stayed a perennial problem. She noted in her diary that she felt at times “like throwing the books at students,” but she soldiered on nonetheless.

Along with her library duties, Edwina also taught courses at the college, usually in German or American literature. Occasionally, though, she was pressed into teaching a subject outside her expertise.

During the First World War, she was tasked with leading 100 students in a course on Connecticut geography. When she protested that she knew nothing about the subject, Charles Beach, President at the time, told her: “Well, nobody else does. So do it. It’s up to you.” Mercifully, she only had to deliver a few lectures before most of the students were drawn into the war effort.

When Edwina became librarian in 1900, the CAC faculty numbered only nineteen and the population of Storrs was a paltry 1,800 persons. Thirty-two and single, she found the social life around campus stifling.

In particular, she resented having to sit out social events due to her unmarried status. Some of the sharpest barbs in her diary were reserved for these occasions.

Writing about one celebration on campus, she sardonically recorded: “Unmarried couples made goo goo eyes and finally anchored by each other’s side, while the few old maids like myself wandered around disconsolately counting the minutes until we could decently leave.”

In later years, Whitney’s social circle widened and she became a fixture in the town, taking on prominent roles in her church, community organizations, and even serving as local historian.

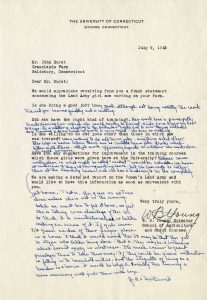

In 1934, Edwina was forced to retire from her position as college librarian, a fact she accepted with bitterness at first. Some of her supporters around campus urged her to challenge the decision, but she declined.

A faculty committee was drawn up to recognize her achievements, and she received an honorary degree at commencement that year. An issue of the school newspaper was also largely dedicated to her legacy.

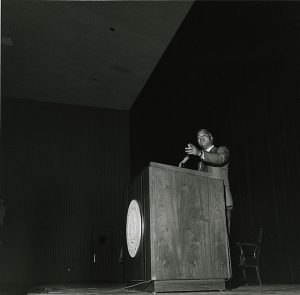

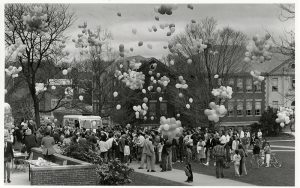

In 1968, on her centennial birthday, the University threw a celebration in her honor, and she passed away two years later in 1970.

Edwina Whitney Residence Hall, named after the former librarian in 1938, still stands on the Storrs campus today, as does her original family home.

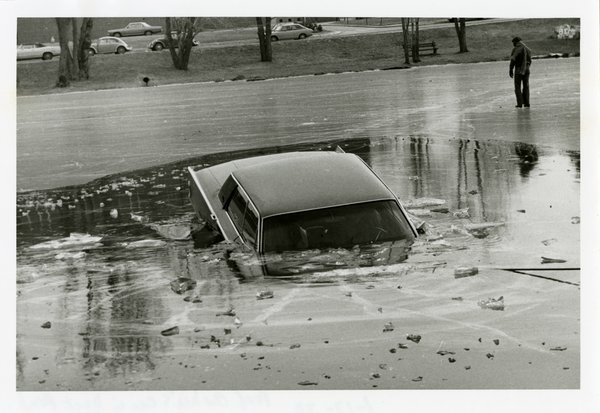

The family home became known as International House in 1964, a gathering place for international students on campus. Later, it held the Division of International Affairs. Now it sits unoccupied, only adding to the picturesque landscape around Mirror Lake.

In 1928, the original building Edwin Whitney built became faculty housing until it was condemned by the state and razed in 1932. Only a stone marking the front-step remains.

A portrait of Edwina Whitney can be found in the Wilbur Cross building, which was constructed in 1938-1939, specifically to be the University’s library.

In a speech, Walter Stemmons, one of UConn’s great chroniclers, said that a university is really just an idea. But surely the books and buildings count for something too. The Whitney family’s story, at least, shows how central they were to the University’s early years.