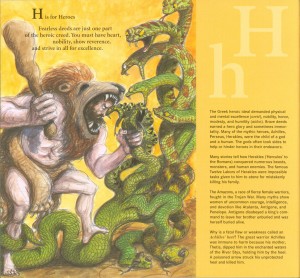

“The Lady of the Castle!—Are we then to journey through deserts waste! Forests drear!—encounter one-eyed giants—destroy fell enchanters—lay waste castles, where ladies fair, and courtly and courageous knights have for centuries remained immured and spellbound—to come at—THE BEGGAR BOY?” (Bellamy 5).

Thus begins Thomas Bellamy’s The Beggar Boy, and to answer his own question, No. Our Mr. Bellamy was avowed to have “no talent for satire” (Baker 33), but has actually tricked us for a moment, led us on to think this is one kind of tale while it is actually another, a contemporary tale of his own time and place: Bellamy was “born in 1745, at Kingston-upon-Thames, in Surrey” (Baker 31), and had “a mind, susceptible to the pleasures of poetry, and indulging in propensities of innate genius. . .[which could] not long relish the business of common life” (Baker 32).

Thus begins Thomas Bellamy’s The Beggar Boy, and to answer his own question, No. Our Mr. Bellamy was avowed to have “no talent for satire” (Baker 33), but has actually tricked us for a moment, led us on to think this is one kind of tale while it is actually another, a contemporary tale of his own time and place: Bellamy was “born in 1745, at Kingston-upon-Thames, in Surrey” (Baker 31), and had “a mind, susceptible to the pleasures of poetry, and indulging in propensities of innate genius. . .[which could] not long relish the business of common life” (Baker 32).

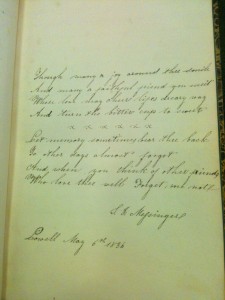

Bellamy thus became a writer, but “from this prospect of happiness he was summoned by death, after an illness of four days, Friday, August 29, 1800” ( Baker 33). Then was the unfinished Beggar Boy without a home, though Bellamy’s “good qualities secured him many friends” (Baker 33), one of whom—Elizabeth Sarah Villa-Real Gooch—completed the novel out of “a sincere friendship for Mr. Bellamy, which commenced many years ago, and continued, without interruption, to the day of his death” (Bellamy 3).

We are thus left with quite a story: after a complex first volume—in which Dame Sympkins, “the lady of the Castle,” dies; her husband remarries, then dies; his new widow Fanny remarries to a man named Goodwin, whom she abandons, while her brother at sea is thought dead (leading to their mother’s death) and returns after being wrecked on French shores and meeting a sympathizer who knows his mentor Admiral Sydney, who has died; and Sydney’s daughter Louisa has disappeared, so that it is necessary for their friend Mr. Lucas, the curate, to go and find her—“’Well!” says the reader, ‘and now we have travelled through one volume, out of three—and no Beggar Boy!’” (Bellamy 101).

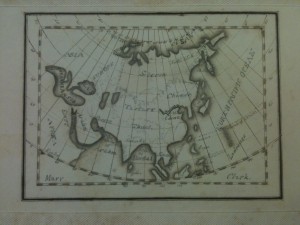

Ay, where is he? “The child of misery is on his way,” the narrator assures us, “refuse not, fair and gentle country-women, your commiseration for—The Sorrows of Alfred!” (101), and so: Louisa Sydney runs away from home, falls into debt, marries, runs away, gives birth to Alfred, and dies; Alfred is abducted by Gypsies, and Martha, his new guardian, rescues him; Alfred is sent to Jamaica; Alfred returns and rescues a rich lady from a band of thugs; the rich lady is employing Martha; knows an admiral M’Bride, who knows Mr. Lucas, and knew Admiral Sydney; Alfred’s father pops up as a robber and M’Bride kills him out of self defense; M’Bride and Lucas get Alfred his grandfather’s estate back, and Alfred marries the rich lady’s daughter, surprising us all that he has now grown up.

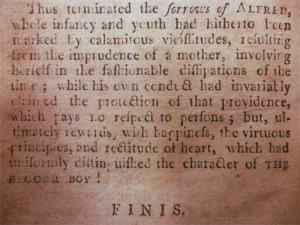

The End. Finis. What are we to make of this? If things aren’t already clear enough: this  is a moral tale, just as we would expect from a man with “an acute moral perception and an invariable affection for the best graces of the heart” (Baker 33), and so the novel concludes, “thus terminated the sorrows of ALFRED, whose infancy and youth had hitherto been marked by calamitous vicissitudes, resulting from the imprudence of a mother, involving herself in the fashionable dissipations of the time; while his own conduct had invariably claimed the protection of that providence, which pays no respect to persons” (340).

is a moral tale, just as we would expect from a man with “an acute moral perception and an invariable affection for the best graces of the heart” (Baker 33), and so the novel concludes, “thus terminated the sorrows of ALFRED, whose infancy and youth had hitherto been marked by calamitous vicissitudes, resulting from the imprudence of a mother, involving herself in the fashionable dissipations of the time; while his own conduct had invariably claimed the protection of that providence, which pays no respect to persons” (340).

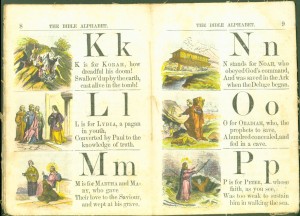

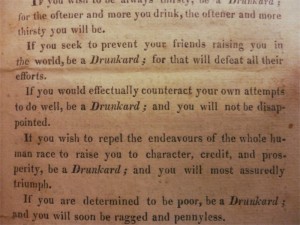

Gentle reader, harken then: Alfred is happy because of “the virtuous principles, and rectitude of heart, which had uniformly distinguished [his] character” (340), securing providence. Note, reader, the constant manner in which virtue is rewarded and vice is punished: coerced into “the abominable vice of drunkenness” (252), “[Alfred’s] ruin was  accomplished and inevitable” (251): he is conscripted against his will, and sent to Jamaica. Such incidents abound throughout, echoing similar sentiments towards drink in American pamphlets found in our archives: “The Advantages and Disadvantages of Drunkenness” (1821), says “if you would effectually counteract your own attempts to do well, be a Drunkard ; and you will not be disappointed” (Collins 3); Nathaniel Gage’s “An Address on Intemperance. Pronounced at Nashua Village, N.H. April 4, 1829,” warns that “intemperance is destroying the fruits of intelligence, the strength of the people” (Gage 12).

accomplished and inevitable” (251): he is conscripted against his will, and sent to Jamaica. Such incidents abound throughout, echoing similar sentiments towards drink in American pamphlets found in our archives: “The Advantages and Disadvantages of Drunkenness” (1821), says “if you would effectually counteract your own attempts to do well, be a Drunkard ; and you will not be disappointed” (Collins 3); Nathaniel Gage’s “An Address on Intemperance. Pronounced at Nashua Village, N.H. April 4, 1829,” warns that “intemperance is destroying the fruits of intelligence, the strength of the people” (Gage 12).

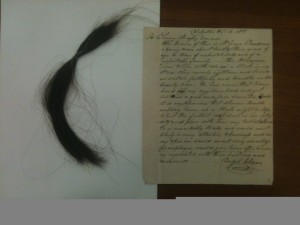

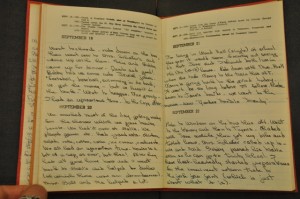

So always in moderation, reader. Note, too, though, Bellamy’s main message, on providence. Providence is the unseen force guiding the novel, illustrated as both human and divine. At some point in the history of our volume, a reader highlighted the passage “alas! My friend, we are apt to murmur at the painful events which nature, in its appointed round, is sure to produce” (Bellamy 65), lamenting cruel fate, yet for Bellamy, providence can be secured through moral action. Alfred behaves well, and is so rewarded. Yet his fortune is due mainly to the people around him acting providentially on his behalf, making providence non-divine: Admiral M’Bride works to get Alfred his inheritance, and explains to others “that Alfred should remain ignorant of the object of the present journey, in case it should prove fruitless of any good to that young man” (Bellamy 297), personally enacting providence in Alfred’s life.

Bellamy’s moral? A sort of golden rule: do well unto others, and others will do well unto you, or, perhaps simply do well to yourself, and others will do well unto you. Take this away if you will, but I take away something more: a novel that through its haphazard plotting enacts its moral, and so a deeper understanding of the form of the moralistic novel, and an appreciation for their apparent absurdity; a closer look at more popular writing of this time period, from a forgotten novelist; and some perspective on the concerns of the time. And what a story! There may be no Deserts Waste! Forests Drear! Fell Enchanters! Castles! or Knights and Ladies! yet where else can you find a story where two ostensible protagonists die within the first ten pages; where our real protagonist shows up late; is kidnapped repeatedly; and can cross the Atlantic and come back in the space of ten pages as if nothing happened?

I think it’s safe to say, only in The Beggar Boy.

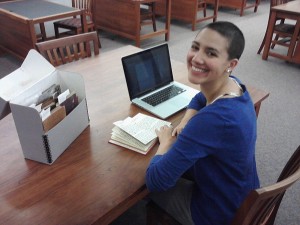

Daniel Allie is a senior undergraduate student in English. For his blog series Hypocrite Lecteur he will spend the Spring 2014 Semester exploring nineteenth-century literature in a variety of genres from the Rare Books Collection housed in Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center.

Works Cited

Baker, David Erskine. “Bellamy, Thomas.” Biographia Dramatica: or, a Companion to the Playhouse. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, et al. 1812. 31-33. Web. Google Books. Accessed 16 February 2014.

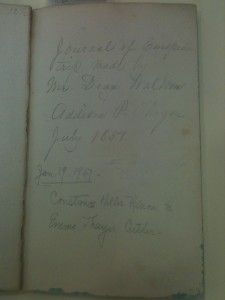

Bellamy, Thomas. The Beggar Boy: A Novel. Alexandria: Cottom and Stewart, 1802. Print. [Dodd Center Call Number: A619]

Collins, F. “The Advantages and Disadvantages of Drunkenness.” Cambridge: Trustees of the Publishing Fund, 1821. Print. [Dodd Center Call Number: WHV 25]

Gage, Nathaniel. “An Address on Intemperance. Pronounced at Nashua Village, N.H. April 4, 1829.” Dunstable: Thayer &Wiggin, 1829. Print. [Dodd Center Call Number: WHV 56]