From all of us here in Archives & Special Collections, we wish you a joyful 2016.

Image taken by Professor Jerauld Manter, year unknown.

UConn Library

Archives and Special Collections Blog

UConn Library

Archives and Special Collections BlogMerry Christmas, everyone! Our reading room will be closed for the two weeks between December 21 and January 4 but please contact us at archives@uconn.edu if you have questions about our collections.

From Christmas Rhymes and Stories, Original and Selected, including a Visit from Santa Claus, by Kriss Kringle, published in 1887.

From Christmas Rhymes and Stories, Original and Selected, including a Visit from Santa Claus, by Kriss Kringle, published in 1887.

It’s National Tango Day! Not in the U.S., though, but in Argentina. That’s as good an excuse as any to put up this photo of a couple dancing a tango on ice from the book “Dancing on Ice,” which you can find in our digital repository.

Here is a page from one of the many holiday books that you can find in the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection. The Miracle of the Potato Latkes: A Hanukkah Story, was written in 1994 by Malka Penn and illustrated by Giora Carmi. This page from the book is shown here courtesy of the author and illustrator.

Smiles, laughter, children’s books and their authors await you at the 24th Annual Connecticut Children’s Book Fair happening this Saturday, November 14 and Sunday, November 15 at the University of Connecticut. The fun begins at 10:00am. Check out this year’s exciting schedule of Authors and Illustrators featuring Ross MacDonald, Wendell Minor, Florence Minor, Cynthia Lord, P. J. Lynch, Jane Sutcliffe, Pamela Zagarenski, and Connecticut’s-own Barbara McClintock. Parking, directions, and links to local attractions, including the Ballard Museum of Puppetry, are available on the Book Fair website. Drop in to hear distinguished illustrators discuss their work, browse the latest releases, attend storytime and other events throughout the day including a visit by Clifford the Big Red Dog!

Smiles, laughter, children’s books and their authors await you at the 24th Annual Connecticut Children’s Book Fair happening this Saturday, November 14 and Sunday, November 15 at the University of Connecticut. The fun begins at 10:00am. Check out this year’s exciting schedule of Authors and Illustrators featuring Ross MacDonald, Wendell Minor, Florence Minor, Cynthia Lord, P. J. Lynch, Jane Sutcliffe, Pamela Zagarenski, and Connecticut’s-own Barbara McClintock. Parking, directions, and links to local attractions, including the Ballard Museum of Puppetry, are available on the Book Fair website. Drop in to hear distinguished illustrators discuss their work, browse the latest releases, attend storytime and other events throughout the day including a visit by Clifford the Big Red Dog!

The Connecticut Children’s Book Fair is a program of the University of Connecticut Libraries and the UConn Co-op. Proceeds from sales at the event are used for the growth of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection in the Archives and Special Collections at the University of Connecticut Libraries.

Busytown, the bustling small town and home to such resident characters as Huckle Cat, Lowly Worm, Mr. Frumble, Police Sergeant Murphy, Mr. Fixit, and Hilda Hippo, was first depicted in the book Richard Scarry’s Busy, Busy World. The fictional town was a central feature in several Richard Scarry books and has been depicted through time in a variety of formats, including games, toys, activity books, and an animated series.

Busytown, the bustling small town and home to such resident characters as Huckle Cat, Lowly Worm, Mr. Frumble, Police Sergeant Murphy, Mr. Fixit, and Hilda Hippo, was first depicted in the book Richard Scarry’s Busy, Busy World. The fictional town was a central feature in several Richard Scarry books and has been depicted through time in a variety of formats, including games, toys, activity books, and an animated series.

Richard Scarry, the popular and much-loved American author and illustrator of over 300 children’s books, is known for such classics as Richard Scarry’s Best Word Book Ever released in 1963, Richard Scarry’s Busy, Busy World (1965), Richard Scarry’s Storybook Dictionary (1966), and What Do People Do All Day (1968). Selling millions of copies during his lifetime, many Scarry books, though regularly updated and re-issused, have never been out of print. Several have have been translated into over 20 languages.

Join us tomorrow evening, Tuesday November 10, 6:00pm for a special guest lecture  “The Story of Richard Scarry’s Busytown” with Scarry’s son, Richard “Huck” Scarry II. Also an artist and author of children’s books, Huck Scarry published a new Scarry picture book for the first time in the U.S. since the elder Scarry’s death in 1994. With Richard Scarry’s Best Lowly Worm Book Ever! Huck Scarry began a season of re-releasing Scarry’s classics to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Richard Scarry’s best-known book, Richard Scarry’s Best Word Book Ever. The guest lecture event will take place in the Class of 1947 Room, Homer Babbidge Library, University of Connecticut in Storrs. The lecture is free and open to the public and is presented in conjunction with the 24th Annual Connecticut Children’s Book Fair taking place at UConn on Saturday and Sunday, November 14 and 15, 2015.

“The Story of Richard Scarry’s Busytown” with Scarry’s son, Richard “Huck” Scarry II. Also an artist and author of children’s books, Huck Scarry published a new Scarry picture book for the first time in the U.S. since the elder Scarry’s death in 1994. With Richard Scarry’s Best Lowly Worm Book Ever! Huck Scarry began a season of re-releasing Scarry’s classics to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Richard Scarry’s best-known book, Richard Scarry’s Best Word Book Ever. The guest lecture event will take place in the Class of 1947 Room, Homer Babbidge Library, University of Connecticut in Storrs. The lecture is free and open to the public and is presented in conjunction with the 24th Annual Connecticut Children’s Book Fair taking place at UConn on Saturday and Sunday, November 14 and 15, 2015.

Richard Scarry’s personal papers and archives, preserved and available in Archives and Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center, document the creation, production, and distribution of his books for children. The archives are part of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection and contain materials and correspondence concerning Scarry’s early work, with Western Publishing and Little Golden Books, beginning in the 1950s. The bulk of the material in the archives concerns the works produced by Scarry during his later association with Random House.

President Bill Clinton came to the University of Connecticut in 1995 to dedicate the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. He returns today, exactly twenty years later, to receive the Thomas J. Dodd Prize in International Justice and Human Rights, along with the international Human Rights Education organization Tostan. We’re delighted to welcome him back to UConn! Here he is at the ceremony on October 15, 1995.

by JoAnn Conrad, Recipient of the 2015 Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant

Part of my ongoing research into children’s picturebooks of the mid-twentieth century has to do with the ways in which the work of illustrators has insinuated itself into the public memory even as the names of individual artists may be relatively obscure. This is the case with the rare female artist and, particularly, Esphyr Slobodkina, as her influence is inversely proportional to the obscurity of her name. “Esphyr Slobodkina . . .helped pave the way for the acceptance of abstract art in the United States and translate[d] European modernism into an American idiom.”[1]

A simple and serendipitous anecdote demonstrates this: While researching her papers at UConn’s Archives and Special Collections this summer, I was living across the street from the UConn Bookstore. One day, I noticed a display in the window announcing “Caps for Sale” [Fig. 1], clearly alluding to one of Slobodkina’s most popular books of the same name [Fig. 2]. The power of the sale poster derives from and depends on the reference to the book, which is assumed to be automatic.

There is a fair amount about Slobodkina’s life and work available. The Finding Aid for the Slobodkina Papers at Archives and Special Collections provides a brief biography as does the website of the Esphyr Slobodkina Foundation. The 2009 Rediscovering Slobodkina: A Pioneer of American Abstraction includes information on her life as well as her contributions to the art world, but the full biography has yet to be written. Esphyr Slobodkina anticipated that it would be written, however, and drafted a comprehensive, detailed, 5-volume manuscript “Notes for a Biographer” which resides in her papers. The Slobodkina Papers contain much more than is in her books – things that would never be published but which give a researcher like me access to insights into the thoughts and motivations of the artist. One of the pleasures of this kind of archival research is not only this intimate and personal connection one makes across time, but also the unexpected revelations into the personality of the artist that informs her work. My intention here is to provide some of those “off the books” glimpses into the work and person – Esphyr Slobodkina.

Esphyr Slobodkina was born to a wealthy Russian-Jewish family in Russia before the Revolution. Continue reading…

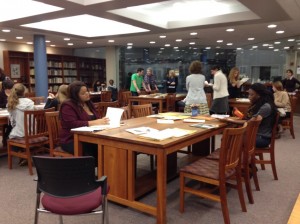

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources. Continue reading

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources. Continue reading

Graduate intern Nick Hurley updates his progress in the Bruce Morrison Papers–

It has been a while since my introductory blog post, and much has happened between then and now! I have examined and rearranged two series of the Morrison Papers (about seven boxes of material) and prepped them for digitization, and also prepared new finding aids for each.

Series VII deals with Morrison’s time on the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform (1993-1997). It is a small collection—only two boxes—but had an interesting mix of correspondence, press clippings, and copies of government documents to look through, and was a good way to ease into my new job at the archives.

Series VIII was far more complex. It deals exclusively with Morrison’s involvement in Irish affairs. Among the five subseries I established in the new finding aid, researchers will now have access to information about topics such as Morrison’s leadership of Americans for a New Irish Agenda (ANIA) and Irish Americans for Clinton-Gore, his work on Irish immigration, and his role in urging President Clinton to take a more active role in the peace process in Northern Ireland.

It’s clear from looking through these papers that Bruce Morrison was a man incredibly committed to his work. His involvement in the Irish peace process, for example, seems manageable until you realize that while he was leading fact-finding missions to Northern Ireland and petitioning the White House for a new Irish agenda, he was also serving on the Commission on Immigration Reform (1993-1997), practicing as an immigration lawyer in New Haven, and chairing the Federal Housing Finance Board (1995-2000). He also had a wife and young son (born 1992) at home.

It’s also clear that Ireland played a huge role in much of his career. In the 1990s, he became a veritable superstar amongst the Irish-American population, due in large part to his authorship of the Immigration Act of 1990. A provision of that bill, known as the “Morrison program”, allotted more than 16,000 visas to immigrants from Ireland and Northern Ireland attempting to enter the United States. For much of the early 1990s, Morrison was a guest of honor at countless social functions at Irish clubs and institutions, and was even named one of Irish America magazine’s Top 100 Irish-Americans.

Here’s what really surprised me, however; Morrison’s upbringing and personal life don’t at all reflect his high standing in the Irish-American community, or the deep interest in all things Ireland that came to define his political career. Adopted as a baby, his Irish roots consist of a biological father who was, in Morrison’s words, “somewhat Irish.” He was raised Lutheran, not Catholic. One reporter offered the following description in a March 1997 article for the Hartford Courant:

No Irish flag waves from his porch on St. Patrick’s Day. He isn’t much of a storyteller, doesn’t quote from W. B. Yeats, and doesn’t sing Irish songs, or even profess to know any of the words. In his home, the paintings and sculptures reveal a preference for primitive art from Africa and South America. Only some expensive Irish crystal ware — gifts and awards from groups in both Ireland and America — offer any clues that Morrison has an Irish connection.

It was clear from my examination of these collections that Morrison was never destined, by virtue of his childhood experiences or family background, for the career he ended up having. So I had to ask; why Ireland? The simple answer is that as a young Congressman, spurred on by reports of human rights abuses in Northern Ireland, he was persuaded to leave the Friends of Ireland, which consisted of politicians who rarely criticized the British and limited their activities to what Morrison called “St. Patrick’s Day blather,” and join instead the Ad Hoc Committee for Irish Affairs, a more “radical” element of Congress which took a deep interest in the Ireland issue.

Even once on the committee, however, his involvement in Ireland was characterized by a certain sense of emotional detachment. In the March 1997 article, Morrison pointed to a “radicalizing experience” in 1987 that began to reverse that trend. While on a fact-finding mission to Northern Ireland, Morrison’s car was stopped by a Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC, a British-backed police force) armored vehicle:

A dozen officers surrounded the car. When he was asked for papers, Morrison handed over his passport, stamped with “Member of Congress.” The policeman refused to return it, and a shouting match ensued, with congressman and officer pulling on the passport. Other officers rifled through the trunk.

Infuriated but ever the lawyer, Morrison pulled out a notepad and began to write down police badge numbers. An RUC officer grabbed the pad. It was a crime, he said, to collect information about security forces. They were released 30 minutes later.

All that would follow—the peace process, the Morrison visas, and the outpouring of support from the Irish community—would now be more than just a political agenda for Morrison. The man himself perhaps said it best:

“Here I had this fortuitous coming together of opportunities that had made me a hero in Irish America and in Ireland . . . and it was like, ‘That’s great, I can just bask in the glory of it all and get upgraded on Aer Lingus [Ireland’s national airline], but I’m an activist. That’s who I am. How do I take this and make something different in the world?’”

Put simply, his dedication to all things Irish came not from his ethnic heritage, but from a life lived as an activist. While attending the University of Illinois, he formed an advocacy group for graduate students, and after his graduation from Yale Law School he practiced at a firm which specialized in “poverty law”, helping those without the means to help themselves. Bruce Morrison went where he was needed, and in the early 1990s, that place just happened to be Ireland, and he just happened to have an Irish background.

Questions of motive aside, one thing is certain: Bruce Morrison has become a cult figure in the Irish-American community, and the prestige he earned from his work in 1990s isn’t likely to fade anytime soon.

[slideshow_deploy id=’5682′]

The first comprehensive exhibition in Germany devoted to the legendary Black Mountain College opened this weekend at the Hamburger Bahnhof – Nationalgalerie in Berlin amid a large crowd and a flurry of interest. The large exhibition showcases archival materials loaned from a variety of repositories in the United States and Europe, and we are thrilled to have materials produced at Black Mountain College exhibited from collections held here in Archives and Special Collections included in the exhibition.

Black Mountain. An Interdisciplinary Experiment 1933 – 1957 encompasses works of art and craft, photography, performance and literature produced at Black Mountain College. Live readings, documentary film, and student programming promise to engage visitors throughout the exhibition which runs from June 5 until September 27, 2015.

In cooperation with the Freie Universität Berlin and the Dahlem Humanities Center, the exhibition at the Nationalgalerie in the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum traces the history of the small college founded in 1933 in North Carolina from its early experimental stages through the artists and teachers that shaped it in years following World War II. “Its influence upon the development of the arts in the second half of the 20th century was enormous; the performatisation of the arts, in particular, that emerged as from the 1950s derived vital impetus from the experimental practice at Black Mountain,” according to the exhibition curators.

Within an architectural environment designed by the architects’ collective raumlabor_berlin, the exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof is showing works both by teachers at the college, such as Josef and Anni Albers, Richard Buckminster Fuller, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Shoji Hamada, Franz Kline, Xanti Schawinsky and Jack Tworkov, and by a number of Black Mountain students, including Ruth Asawa, Ray Johnson, Ursula Mamlok, Robert Rauschenberg, Dorothea Rockburne and Cy Twombly. A wealth of photographs and documentary film footage, as well as publications produced by the college, offer an insight into the way in which the institute worked and into life on campus.

…

In the first few years of its existence, the college was strongly shaped by German and European émigrés – among them several former Bauhaus members such as Josef and Anni Albers, Alexander “Xanti” Schawinsky and Walter Gropius. After the Second World War, the creative impulses issued increasingly from young American artists and academics, who commuted between rural Black Mountain and the urban centres on the East and West Coast. Right up to its closure in 1957, the college remained imbued with the ideas of European modernism, the philosophy of American pragmatism and teaching methods that aimed to encourage personal initiative as well as the social competence of the individual.

Accompanying the exhibition is the artistic project Performing the Black Mountain Archive by Arnold Dreyblatt, a Berlin-based media artist and composer currently teaching as Professor of Media Art at the Muthesius Kunsthochschule in Kiel. The project incorporates the live performance of archival material Dreyblatt collected in the Black Mountain Archives in the United States. Including students from different disciplines like sculpture, painting, media art, sound art, music, dance, theater, typography and literature, the project “investigates the interdisciplinarity of Black Mountain’s pedagogical approach.” Dreyblatt invited students from ten European art academies – amongst them his own class – who present the material in the form of readings, concerts and performances over the entire duration of the exhibition. Dreyblatt was interviewed recently about the project by Verena Kittel of Black Mountain Research, based at the Museum.

Stay tuned for information regarding another exhibition featuring Black Mountain College materials, loaned from Archives and Special Collections, this October at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Boston. Details can be found on their forthcoming exhibitions site!