As of June 30, 2015, Terri J. Goldich will retire from the University of Connecticut after a career of over 38 years with the UConn Libraries. Ms. Goldich has had the good fortune to serve as the curator for the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection in Archives & Special Collections in a full-time capacity since February of 1998. Care of the NCLC will be taken on by Kristin Eshelman, a highly skilled archivist currently on staff in the Archives. Ms. Eshelman’s contact information is available on the website at http://doddcenter.uconn.edu/asc/about/staff.htm.

Category Archives: What’s Happening in the Archives

Archivist Graham Stinnett featured on Queer!NEA

I believe in the principles of archives as tools for engagement with a broader societal understanding of itself and how it can be leveraged for change in society, so building on these collecting areas is very beneficial. We are always being documented, it is our job to engage the creation of memory from that documentation.

Check out the latest post on Queer!NEA, a blog for New England Archivists’ Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Issues Roundtable, featuring an interview with our very own Graham Stinnett, Archivist for Human Rights and Alternative Press Collections. Graham tells us about his professional interests and the array of activities that occupy his days here at UConn with students and faculty. He also reflects on the critical, tangible value of archives today “to promote the dialectic between the then and now”…

When considering the basis of text communication in social media platforms today which could be the closest comparison to the channels of alternative press, these outlets have more in common than they do in division. My goal is to promote the dialectic between then and now. Beyond the narrative that all movements toward rights are valuable and worth documenting, my interest has been to promote the intersections where students have made impacts through documentation in the past which now can inform the present context of identity, recreation, sociability and agency. Having said all that, I don’t think we as archivists have yet understood how to deal with today’s alternative press, which is why these conversations are so important.

Laurie Anderson’s Big Science: Gender, Automation, and Created Beings

“O Superman. O judge. O Mom and Dad. Mom and Dad,” begins performance artist Laurie Anderson’s “O Superman.” Half-sung, half-spoken, and captivatingly hypnotic, the eight-minute song featured on Anderson’s 1982 album Big Science reached number two on the U.K. charts in the early 1980s.

Anderson’s work strikes an interesting balance between abstraction and accessibility. Despite the popularity of “O Superman” and the rest of Big Science, Anderson encodes her work with rich references to literary texts, operas, cultural trends and pop culture events. The album most extensively engages with the relationship among communication, technology, and political affairs. “Big Science,” after all, is a term used to describe the shift during and after World War II toward government-funded, large-scale scientific projects principally devoted to the development of new weapons and tools.

Furthering her engagement with technology are the instruments and techniques Anderson uses to produce her music. The spoken text of “O Superman,” for example, is dictated through a vocoder, a synthesizer used to reproduce human speech. Anderson uses the technology to make her voice sound synthetic, therefore mimicking the automatic voice of an answering machine and blurring the assumed boundaries between the natural and the artificial. But the most fascinating aspect of Anderson’s performance art is both its timeliness and timelessness—her songs are just as topically relevant and profound today as they were over thirty years ago.

I had the opportunity to listen to Anderson’s vinyl LP using the Dodd Center’s electronic equipment. I’ve compiled the digitized tracks of Anderson’s Big Science here for those interested in listening at home.

I had the opportunity to listen to Anderson’s vinyl LP using the Dodd Center’s electronic equipment. I’ve compiled the digitized tracks of Anderson’s Big Science here for those interested in listening at home.

-Giorgina Paiella

Intern Giorgina Paiella is an undergraduate student majoring in English and minoring in philosophy and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. In her new blog series, “Man, Woman, Machine: Gender, Automation, and Created Beings,” she explores treatments of created and automated beings in historical texts and archival materials from Archives and Special Collections.

Earth Day 2015: Wild Beauty Through the Lens of Edwin Way Teale

[slideshow_deploy id=’5502′]

The long fight to save wild beauty represents democracy at its best. It requires citizens to practice the hardest of virtues – self-restraint. Why cannot I take as many trout as I want from a stream? Why cannot I bring home from the woods a rare wildflower? Because if I do, everybody in this democracy should be able to do the same. My act will be multiplied endlessly. To provide protection for wildlife and wild beauty, everyone has to deny himself proportionately. Special privilege and conservation are ever at odds.

Edwin Way Teale, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and naturalist, spent his life observing and recording his vivid experiences in, and encounters with, the natural world. We honor Teale and his legacy this Earth Day 2015 with a selection of photographs from his rich archive being preserved here at UConn. The excerpt is from Teale’s 1953 book Circle of the Seasons. The pictures were selected by Kristin Eshelman, Archivist for Multimedia Collections in Archives and Special Collections.

Tomorrow: Fred Ho Fellow Marie Incontrera Performs with the Eco-Music Big Band

UConn welcomes Marie Incontrera – conductor and band-leader of the Green Monster Big Band (Fred Ho’s premiere big band) and the Eco-Music Band – to campus tomorrow April 14 at 12:45pm for a public performance. The Eco-Music Big Band is a 15-piece, multi-generational big band that is committed to continuing the prodigious compositional and creative legacy of Fred Ho. The ensemble also performs the works of the overlooked composers of 20th century (such as Cal Massey), and provides a platform for the next generation of big band composers.

UConn welcomes Marie Incontrera – conductor and band-leader of the Green Monster Big Band (Fred Ho’s premiere big band) and the Eco-Music Band – to campus tomorrow April 14 at 12:45pm for a public performance. The Eco-Music Big Band is a 15-piece, multi-generational big band that is committed to continuing the prodigious compositional and creative legacy of Fred Ho. The ensemble also performs the works of the overlooked composers of 20th century (such as Cal Massey), and provides a platform for the next generation of big band composers.

Ms. Incontrera has been awarded the 2015 Fred Ho Fellowship, named for Asian American Musician, composer, writer and activist Fred Ho. Established by the Asian and Asian American Studies Institute, the Fred Ho Fellowship supports research in the Fred Ho Papers, which are held in Archives and Special Collections at UConn.

Fred Ho’s conducting protégé before his death in April of 2014, Marie Incontrera conducted the Green Monster Big Band for Fred Ho’s final album.

Ms. Incontrera’s work spans queer opera, political big band, and music-for-the-oppressed. As a composer, Marie has been a recipient of the Miriam Gideon Composition Award, a winner of  the Remarkable Theater Brigade Art Song Competition, the 2011 Vocalessence / American Composers Forum “Essentially Choral” readings, and a finalist in the Iron Composer 2010 competition. She has been awarded grants from Meet the Composer Metlife Creative Connections, Foundation for the Contemporary Arts, Puffin, and New York Women Composers Seed Money Grant. Commissions have come from the Young New Yorkers Chorus, Remarkable Theater Brigade, ANALOGarts, Brooklyn Art Song Society, ANIKAI Dance Theater, MOIRAE Ensemble, Beth Morrison Productions, and Atlanta Opera. Her work has been performed in Carnegie Hall, Symphony Space, Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Meridian Arts Festival in Bucharest, Roulette, Galapagos Art Space, WOW Cafe Theatre, highSCORE Festival, and other respected venues across the United States and internationally.

the Remarkable Theater Brigade Art Song Competition, the 2011 Vocalessence / American Composers Forum “Essentially Choral” readings, and a finalist in the Iron Composer 2010 competition. She has been awarded grants from Meet the Composer Metlife Creative Connections, Foundation for the Contemporary Arts, Puffin, and New York Women Composers Seed Money Grant. Commissions have come from the Young New Yorkers Chorus, Remarkable Theater Brigade, ANALOGarts, Brooklyn Art Song Society, ANIKAI Dance Theater, MOIRAE Ensemble, Beth Morrison Productions, and Atlanta Opera. Her work has been performed in Carnegie Hall, Symphony Space, Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Meridian Arts Festival in Bucharest, Roulette, Galapagos Art Space, WOW Cafe Theatre, highSCORE Festival, and other respected venues across the United States and internationally.

The Fred Ho Fellowship provides support to a faculty member, doctoral candidate or independent scholar who has a demonstrated research interest in the Fred Ho Collection. The Fred Ho Fellow is required to give a public lecture at the University of Connecticut and to reference the collection in his or her published works.

@ NYC: Alice Notley Reading / Ed Sanders Drawings and Daybooks / Sharon Olds Pens Poems for You

Long a hub for hearing the poetry and poetic voices of the now, New York City next week and the week after hosts some of the best poetry events and exhibitions happening during this National Poetry Month.

Long a hub for hearing the poetry and poetic voices of the now, New York City next week and the week after hosts some of the best poetry events and exhibitions happening during this National Poetry Month.

On Tuesday, April 14, the prolific and prize-winning poet Alice Notley will read her work at the City University of New York Center for the Humanities. Erica Kaufman, editor of the ever-fresh and propitious Lost & Found publication series, an initiative of the CUNY Center for the Humanities, will lead a conversation with Notley during the program.

While you are in the City, see the rarely exhibited notebooks and drawings of the poet, musician, activist Ed Sanders on display at the Poet’s House, located on its serene perch at 10 River Terrace. During the course of a long and diverse career Sanders used a glyphic alphabet, a script of hand-drawn characters, symbols, and graphemes. In his words, “a Glyph is a drawing that is charged with literary, emotional, historical or mythic, and poetic intensity.” Curated by Ammiel Alcalay and Kendra Sullivan, the show displays pictures and manuscripts by Sanders from 1962 to the present.

On Thursday, April 23, Pulitzer Prize-winner Sharon Olds, and Bob Holman, founder of the Bowery Poetry Café, will sit in a booth (inspired by Lucy’s booth from the Peanuts comic strip) and write poems for those who request one. The Poet is In: takes place in the new Fulton Street Station and features an array of award-winning poets, including NY State Poet Laureate Marie Howe. Free and open to the public, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Replicating the Human Voice: Gender, Automation and Created Beings

“Hello, I’m here.” Throaty, warm, and incredibly human, the first lines spoken by Samantha, the incorporeal female operating system in Spike Jonze’s 2013 film Her, are a far cry from the mechanical voice recognition technologies that we are used to. In addition to its thought provoking philosophical predictions about the near-future, Jonze’s film also hones in on the ideal of voice-replication technology: an artificially intelligent system so natural and intuitive that we can fall in love with it.

Replicating the intricacies of human characteristics and behaviors in non-sentient technologies is far from a new curiosity. Throughout history, automata creators worked to imbue automata with the ability to pen poems, perform acrobatics, play musical instruments, and bat their eyelashes, and these self-operating  machines were often admired and judged for their ability to replicate human behaviors. In perhaps the most dramatic fictional interaction with an automaton that blurs the lines separating human from machine, protagonist Nathaniel in E.T.A. Hoffmann’s short story “The Sandman” falls in love with automaton Olympia, whom he mistakes for a human female.

machines were often admired and judged for their ability to replicate human behaviors. In perhaps the most dramatic fictional interaction with an automaton that blurs the lines separating human from machine, protagonist Nathaniel in E.T.A. Hoffmann’s short story “The Sandman” falls in love with automaton Olympia, whom he mistakes for a human female.

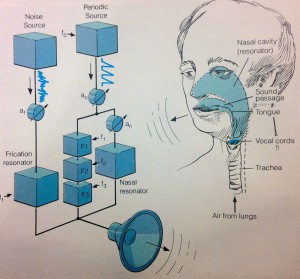

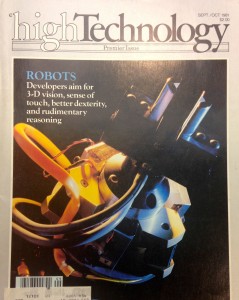

If imitation and replication of human characteristics is one of the driving forces in the creation of artificial beings, it is also one of the greatest challenges. Moving away from automata and toward operating systems and other examples of artificial intelligence, reproduction of human speech is one of the greatest hurdles to clear if we are to produce operating systems like Jonze’s fictional Samantha. The 1981 premiere issue of High Technology affirms that the simulation of human speech has historically been one of the most elusive replication technologies. One article, “Talking Machines Aim For Versatility,”discusses various methods used to replicate speech and reflects upon the value of machines that are capable of producing and understanding human speech.

At the time, most recordings (like the voice on the operator line) consisted of actual recordings of human speech or utilized early word synthesis technologies that tended to sound flat and robotic. Higher-end technologies were very expensive; the Master Specialties  model 1650 synthesizer, for example, was $550 for only a one-word vocabulary, and each additional word cost $50, so the technology was very cost restrictive. Technologies have vastly evolved since the time of rudimentary “talking machines,” but the article discusses the potential of speech synthesis and compression technologies that would streamline the process of stringing phonemes (the smallest speech units) into complete sentences, therefore maximizing speech output, concepts which have influenced current speech synthesis techniques. While there are various approaches to “building” voices, the most common technique in the modern day is concatenative synthesis. A voice actor is recorded reading passages of text, random sentences, and words in a variety of cadences, which are then combined with other recording sequences by a text-to-speech engine to form new words and sentences. The technique vastly expands upon the range and comprehensiveness of operating systems like Apple’s Siri.

model 1650 synthesizer, for example, was $550 for only a one-word vocabulary, and each additional word cost $50, so the technology was very cost restrictive. Technologies have vastly evolved since the time of rudimentary “talking machines,” but the article discusses the potential of speech synthesis and compression technologies that would streamline the process of stringing phonemes (the smallest speech units) into complete sentences, therefore maximizing speech output, concepts which have influenced current speech synthesis techniques. While there are various approaches to “building” voices, the most common technique in the modern day is concatenative synthesis. A voice actor is recorded reading passages of text, random sentences, and words in a variety of cadences, which are then combined with other recording sequences by a text-to-speech engine to form new words and sentences. The technique vastly expands upon the range and comprehensiveness of operating systems like Apple’s Siri.

The High Technology article reflects that because machines would be able to communicate in a form that is natural to humans, they are more equipped to fulfill “the role of mankind’s servants, advisors, and playthings.” Over thirty years later, this goal is still extraordinarily relevant, especially as artificially intelligent systems become more integrated into consumer products like phones, tablets, cars, and security systems. Furthermore, advancements in voice recognition and synthesis technologies have benefitted individuals with impairments who require speech-generating devices to communicate verbally. There are, of course, many challenges that still remain, including the ability of these systems to understand different human accents and dialects. Creating believable artificial speech, however, still harkens back to the greatest challenge in the evolution of these technologies: authenticity. Humans are able to register subtle changes in tone and inflection when we communicate with each other, and these subtleties are currently difficult to replicate in artificially intelligent systems, which explains why we can easily discern a human voice from that of a machine. Jonze’s film suggests that clearing this authenticity hurdle is essential to our ability to truly connect with our technology. Far from the utilitarian “servants, advisors, and playthings” suggested in the High Technology article, intuitive and human-like operating systems could alter our emotional relationship with machines to the extent that they become our confidants and romantic partners.

Intern Giorgina Paiella is an undergraduate student majoring in English and minoring in philosophy and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. In her new blog series, “Man, Woman, Machine: Gender, Automation, and Created Beings,” she explores treatments of created and automated beings in historical texts and archival materials from Archives and Special Collections.

Man, Woman, Machine: Gender, Automation, and Created Beings – An Examination of Early X-Rated Video Games

The issue of sexism in video games may seem like a modern one, especially in light of events like the recent GamerGate controversy. Although discussions about violence and sexism in video games are still extraordinarily relevant in the present day, they actually have a history dating back to 1980s digital culture. In the early 1980s, when video game production was on the rise, these discussions introduced new ethical questions about technological representations.

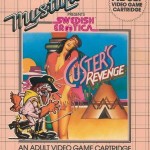

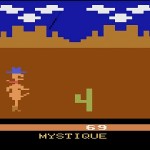

I recently looked through feminist alternative press publications like Off Our Backs and New Women’s Times. These periodicals discuss the 1982 release of a video game called Custer’s Revenge, designed for the Atari 2600 video game console by American Multiple Industries (AMI). The goal of the game is to maneuver a naked and erect General Custer across the desert, arrows flying, toward a red-skinned, dark-haired Native American woman tied to a cactus. After he reaches the woman, he rapes her as his revenge and reward—as the tagline of the game notes, “you score, when you score.” In the 1980s, video game producers like Playaround and AMI started to churn out many x-rated video games, including “Beat ‘em and Eat ‘em,” “Harem,” and “Bachelor Party.” The latter game features eight naked women and one man, where the object of the game is to maneuver the man to each of the eight women, scoring a point after each “victory” and causing the female figure to physically disappear from the screen after the conquest. These games were produced in response to a growing demand for pornographic games, which were expected to gross more than $1 billion annually on the adult market. Although sale of the game was restricted to minors, this did not preclude younger gamers from being exposed to it. Atari even filed a lawsuit against AMI because of the negative attention and association drawn between the system and Custer’s Revenge.

I recently looked through feminist alternative press publications like Off Our Backs and New Women’s Times. These periodicals discuss the 1982 release of a video game called Custer’s Revenge, designed for the Atari 2600 video game console by American Multiple Industries (AMI). The goal of the game is to maneuver a naked and erect General Custer across the desert, arrows flying, toward a red-skinned, dark-haired Native American woman tied to a cactus. After he reaches the woman, he rapes her as his revenge and reward—as the tagline of the game notes, “you score, when you score.” In the 1980s, video game producers like Playaround and AMI started to churn out many x-rated video games, including “Beat ‘em and Eat ‘em,” “Harem,” and “Bachelor Party.” The latter game features eight naked women and one man, where the object of the game is to maneuver the man to each of the eight women, scoring a point after each “victory” and causing the female figure to physically disappear from the screen after the conquest. These games were produced in response to a growing demand for pornographic games, which were expected to gross more than $1 billion annually on the adult market. Although sale of the game was restricted to minors, this did not preclude younger gamers from being exposed to it. Atari even filed a lawsuit against AMI because of the negative attention and association drawn between the system and Custer’s Revenge.

The first game of its kind to be released, Custer’s Revenge received significant attention in the press. Moreover, the game’s fusion of sexist and racist content created uproar in the activist community. Members of organizations like the New York Chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW), Women Against Pornography (WAP), and the American Indian Community House (AICH) organized an October 1983 protest against the inclusion of racism, sexual exploitation, pornography, and profiteering in video games with the hope of pulling pornographic games from store shelves. Denise Fuge, then-president of NY NOW, reflected upon how sexist video games push teenage boys closer to our culture’s acceptance of recreational violence against women. In response, representatives from AMI stated that the game is simply harmless fun depicting “an act of two consenting adults” and therefore could not be construed as enacting violence on women.

Custer’s Revenge was ultimately pulled from the market. The release of inappropriate video games presented new ethical questions about technological representations, the most important of which I will refer to as “moral slippage.” Both in the era of these early pornographic games and in the current day, many debates focus on the extent to which fictional representations like video games can influence real-life behavior. Copycat behavior and replication of violent acts that are depicted in films, music, and games are not uncommon in violent crimes—after all, there is no value-free pop culture. This is not to say that all individuals who play violent games are themselves violent or sexist, but young populations in particular are vulnerable to accepting and adopting problematic views. Custer’s Revenge, for example, was not simply a game or harmless fun, but rather promoted rape culture and racism.

Custer’s Revenge was ultimately pulled from the market. The release of inappropriate video games presented new ethical questions about technological representations, the most important of which I will refer to as “moral slippage.” Both in the era of these early pornographic games and in the current day, many debates focus on the extent to which fictional representations like video games can influence real-life behavior. Copycat behavior and replication of violent acts that are depicted in films, music, and games are not uncommon in violent crimes—after all, there is no value-free pop culture. This is not to say that all individuals who play violent games are themselves violent or sexist, but young populations in particular are vulnerable to accepting and adopting problematic views. Custer’s Revenge, for example, was not simply a game or harmless fun, but rather promoted rape culture and racism.

Although modern games are not as overt as Custer’s Revenge, they still incorporate troubling sexual content and depictions of violence. Despite its incredibly loaded content, the pixelated simplicity of Custer’s Revenge allowed many to brush it off as harmless in its time. Simulation and interactivity have always been integral aspects of gaming. Technology has greatly advanced since the days of early gaming, however, resulting in modern games that contain more graphic and realistic content. This heightened realism intensifies the debate about sexist and violent video games in the modern day because it further blurs the boundary separating gamer, game interface, and reality.

Intern Giorgina Paiella is an undergraduate student majoring in English and minoring in philosophy and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. In her new blog series, “Man, Woman, Machine: Gender, Automation, and Created Beings,” she explores treatments of created and automated beings in historical texts and archival materials from Archives and Special Collections.

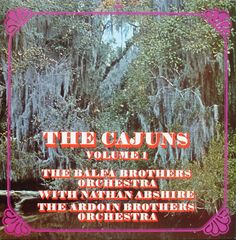

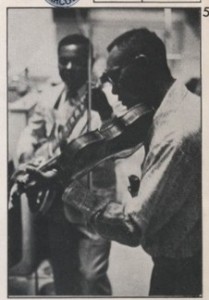

A Language of Song: The Cajuns

The series A Language of Song features the words of Samuel Charters and the recordings he produced as preserved in The Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture at the University of Connecticut. The series is a tribute to the great Samuel Charters – poet, novelist, translator of Swedish poets, and renowned scholar of the blues, jazz, and musical culture of the African diaspora. Samuel Charters died on March 18 at the age of 85.

In the second post in the series, together with a personal remembrance by friend and UConn Libraries staff member Nicholas Eshelman, Mr. Charters describes his recording sessions in Louisiana with Cajun and Zydeco musicians including the great accordion player Nathan Abshire.

In the second post in the series, together with a personal remembrance by friend and UConn Libraries staff member Nicholas Eshelman, Mr. Charters describes his recording sessions in Louisiana with Cajun and Zydeco musicians including the great accordion player Nathan Abshire.

The sessions were released on a series of record albums including The Cajuns – Vol.1: Balfa Brothers Orchestra With Nathan Abshire (SNTF 643 Sonet, 1973). All of the recordings were done at the La Louisianne Studio, Lafayette, Louisiana. The Charters Archives holds the recordings and documents relating to the recordings, such as the studio log sheets.

Sonet Grammofon was interested in a wide range of American music, and over a period of several years I recorded a number of Cajun groups. The trips were usually in connection with other recordings that I was doing western Louisiana – often Rocking Dopsie – but also Bill Haley and the Comets, since I traveled to Nashville or Muscle Shoals for his albums. There was an initial double album set titled The Cajuns, and a number of individual Cajun albums, including a documentary of the famed Mamou Cajun Hour radio broadcasts from Fred’s Lounge on the main street of Mamou.

In December, 1972 I finished a session with Haley in Nashville and traveled on to Lafayette, Louisiana to do a broad documentation of the musical scene there. I worked with four groups, and rounded out the sessions with instrumental duets by talented accordion player Bessyl Duhon and a guitarist. The sessions captured exciting music that could not be duplicated, though I was able to record several other excellent groups a few years later. For this album the Balfa Brothers recorded with the great accordion player Nathan Abshire and the superb two violin team of Dewey Balfa and Merlin Fontenot, and on later recordings with the group neither Abshire or Fontenot took part. The Ardoin Brothers recorded with young Gus Ardoin playing the accordion, and he was tragically killed in a road accident only a few months later.

I first met Sam Charters in 2001 when my wife, Kristin, took a job at UConn that included curatorship of the Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture. Meeting Sam was a big deal for me because my brothers and I had grown up listening to the records he produced, pouring over his liner notes and learning more from his great book, The Country Blues. This was in the 1970’s when finding the blues, jazz and folk LPs we loved in a small Pennsylvania town was nearly impossible, as was finding any good information on how the music came to be. This made every record we did scrounge up something precious, to be listened to over and over, so for this I felt I owed him a great debt and was more than a little nervous about meeting him.

I first met Sam Charters in 2001 when my wife, Kristin, took a job at UConn that included curatorship of the Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture. Meeting Sam was a big deal for me because my brothers and I had grown up listening to the records he produced, pouring over his liner notes and learning more from his great book, The Country Blues. This was in the 1970’s when finding the blues, jazz and folk LPs we loved in a small Pennsylvania town was nearly impossible, as was finding any good information on how the music came to be. This made every record we did scrounge up something precious, to be listened to over and over, so for this I felt I owed him a great debt and was more than a little nervous about meeting him.

Sam and Ann had invited us to their home, and we were privileged for this to happen many more times over the years. I realized I could spend all evening asking him questions like “Did you know Gary Davis?” “What was Moe Asch / Dewey Balfa / John Fahey like?” And not just because he always graciously answered but also because there was no end to the list of remarkable people he’d known, produced, helped or counted as friends. But by then he’d given enough interviews in his life that he’d grown weary of them and I certainly didn’t want to pester him, in his own living room, with questions he’d been asked thousands of times before. Besides, it was just as fun to talk to him and Ann about other things, such the differences between national styles of aquavit (with samples!) or to hear stories about his hunting caribou in Alaska (for subsistence, not sport) or of the colorful artistic and literary types he and Ann knew in Sweden.

I had only known of Sam as a record producer and scholar of folk music and jazz. I soon learned that he was also a novelist, poet, translator, excellent classical pianist, jug,  washboard, banjo and clarinet player, Korean war veteran, art collector, jazz musician and literary scholar. And I’ve probably left some things out. He was also tireless.

washboard, banjo and clarinet player, Korean war veteran, art collector, jazz musician and literary scholar. And I’ve probably left some things out. He was also tireless.

Into his 70’s and 80’s he traveled extensively and seemed to never stop working or finding new additions to the Charters’ Archive. Crazy things would happen to him in his travels. On a trip to Scotland to visit his ancestral home town, he stopped to admire the sights and was approached by a local who recognized him. She was the co-owner of Document Records, a company that publishes meticulously documented collections of rare American music. She and her husband, the other co-owner, had been inspired by Sam and were great admirers. They invited Sam in to chat and the result was the UConn Archives receiving the huge full catalog of the Document label for inclusion in Sam and Ann’s collection.

It was a tremendous honor to know Sam Charters. I’ve never met anyone else like him and certainly never will again. His contribution to music, especially American music, is enormous and invaluable. And even though Sam is gone, his work and the music he loved, studied and recorded will be with us forever. One of the last things I wrote to Sam was that the Charters’ archive is in good, loving hands. I know someone who will see to that.

– Nicholas Eshelman

Thursday’s Teale Lecture: Ecological Imperialism Revisited – Disease, Commerce and Knowledge in a Global World

Four decades ago, the ideas put forth by Alfred Crosby and William McNeill in The Columbian Exchange and Plagues and Peoples forever changed the importance historians put on the role of cultural and biological exchange between the old and new world. The idea that the transfer of diseases from one population to another played as important a role in empire-building as our human conquests became embedded in our cultural narrative.

Four decades ago, the ideas put forth by Alfred Crosby and William McNeill in The Columbian Exchange and Plagues and Peoples forever changed the importance historians put on the role of cultural and biological exchange between the old and new world. The idea that the transfer of diseases from one population to another played as important a role in empire-building as our human conquests became embedded in our cultural narrative.

This Thursday, March 26, at 4 pm in the Konover Auditorium, Dodd Research Center, Gregg Mitman’s lecture examines how American military and industrial expansion overseas helped bring into being new views of nature and nation that would, in turn, become the scientific foundation upon which later historical narratives of ecological imperialism relied. This event is free and open to the public.

Gregg Mitman is the Vilas Research and William Coleman Professor of History of Science, Medical History, and Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His teaching and research interests span the history of science, medicine, and the environment in the United States and the world, and reflect a commitment to environmental and social justice.

The Edwin Way Teale Lecture Series brings leading scholars and scientists to the University of Connecticut to present public lectures on nature and the environment. The series is named for the Pulitzer Prize-winning author and naturalist Edwin Way Teale, whose papers reside in UConn’s Archives and Special Collections.

Co-sponsored by University of Connecticut Libraries, Human Rights Institute, Center for Conservation and Diversity, Graduate School, and several University departments including Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Economics, and Political Science.

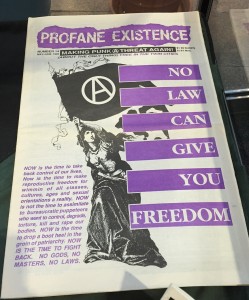

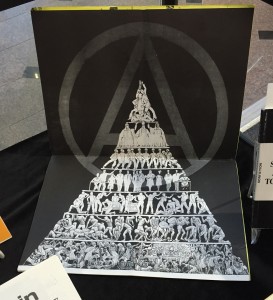

Race and Anarchy Symposium This Week Features Alternative Press Collection

Rare anarchist and race-related publications from the Alternative Press Collection are now on view in the Archives’ McDonald Reading Room. The special exhibition in Archives and Special Collections is curated by Archivist Graham Stinnett and will launch the Race and Anarchy Symposium taking place at UConn on Thursday, March 26 through Friday, March 27.

Rare anarchist and race-related publications from the Alternative Press Collection are now on view in the Archives’ McDonald Reading Room. The special exhibition in Archives and Special Collections is curated by Archivist Graham Stinnett and will launch the Race and Anarchy Symposium taking place at UConn on Thursday, March 26 through Friday, March 27.

Drawn from a wide-ranging collection of anarchist materials that dates from the late 1800s to the present, the selection on display includes ephemeral printings and periodicals of anarchist thinkers and collectives from the 1960s through the early 1990s. Printed in Chinese, English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese and Spanish, the collection documents the international struggle against oppression and hierarchical structures.

A viewing and reception at the Dodd Research Center is scheduled for 2:00pm to 3:30pm on March 26, before Opening Remarks at 3:30pm in the Class of 47 Room in Babbidge Library.

The Race and Anarchism Symposium is free and open to the public. The symposium will offer explorations on theories and the history of anarchy when examined through the lens of critical work on class, gender, indigeneity, race, and sexuality. Presenters include UConn faculty, grassroots organizers, and international scholars and theorists.

The event is co-sponsored by the African American Cultural Center, Africana Studies Institute, Asian and Asian American Studies Institute, El Instituto, the Humanities Institute, the Philosophy Department, the Department of Political Science and the Rainbow Center at UCONN.

The event is co-sponsored by the African American Cultural Center, Africana Studies Institute, Asian and Asian American Studies Institute, El Instituto, the Humanities Institute, the Philosophy Department, the Department of Political Science and the Rainbow Center at UCONN.

A Language of Song: Tribute to Samuel Charters

In tribute to the great Samuel Charters – poet, novelist, translator of Swedish poets, and renowned scholar of the blues, jazz, and musical culture of the African diaspora – we feature in coming weeks the words and recordings of Samuel Charters, collected and preserved in The Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture at the University of Connecticut. Samuel Charters died on March 18 at the age of 85.

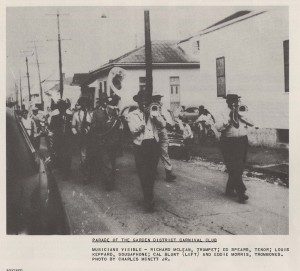

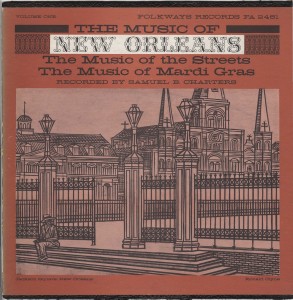

Before Samuel Charters’ seminal book The Country Blues was published in 1959, Mr. Charters had been researching and conducting field recordings of the rich musical traditions of New Orleans. In his writings and interviews throughout his life, Mr. Charters often recalled his childhood, immersed in the sounds of classical music and jazz. In 1956, Folkways Records released The Music of New Orleans. The Music of the Streets. The Music of Mardi Gras, recorded by Samuel Barclay Charters and produced by Moses Ash. In his extensive liner notes, Mr. Charters writes:

Before Samuel Charters’ seminal book The Country Blues was published in 1959, Mr. Charters had been researching and conducting field recordings of the rich musical traditions of New Orleans. In his writings and interviews throughout his life, Mr. Charters often recalled his childhood, immersed in the sounds of classical music and jazz. In 1956, Folkways Records released The Music of New Orleans. The Music of the Streets. The Music of Mardi Gras, recorded by Samuel Barclay Charters and produced by Moses Ash. In his extensive liner notes, Mr. Charters writes:

“The aim of this group of recordings – done in the city in the seven years between 1951 and 1958 – was to find and preserve as much of the cities musical tradition as possible. Here is the music of the brass bands, the dance halls, Mardi Gras, and the music of the streets themselves. The music of shoe shine boys, vegetable criers, guitar players, and street evangelists. The music that was recorded was as much as possible the distinctive music of the city.”

Mr. Charters’ book Jazz New Orleans, 1885-1957 followed in 1958. In his inventory to The Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture, Mr. Charters tells us the story behind the book:

“Walter C. Allen was a research chemist and jazz hobbiest who published a series of Jazz Monographs, of which this was Number 2. He was responsible for typing the manuscript and designing the book, which came out a few months after I sent him the manuscript. The book had involved several years of research in New Orleans and then a long period of writing, and my advance against royalties from Walter was $5, which even that long ago didn’t really seem like a lot of money.”

Excerpted below from the liner notes of The Music of New Orleans. The Music of the Streets. The Music of Mardi Gras., is Samuel Charters.

New Orleans is a gentle, sprawling city lying between Mississippi River and Lake Panchartrain on the Mississippi delta in southern Louisiana. In its early years the city grew beside the river, and against the levees the small streets follow its great crescent curve. …

The city’s remoteness and its colorful past have given it an easy self-assurance and a feeling of continuing tradition that is very different from anything else in America. There is an open disinterest toward contemporary art, music and culture that dismays the energetic outsider who moves to the city. There is almost as little conscious effort made to preserve the city’s own cultural traditions. It is a relatively poor city, but it is a very relaxed city. This may be because even in the poorer neighborhoods the streets are lined with one story wooden houses, rather than large tenements. There is a feeling of spaciousness and sunlight. The weather, despite the hot summers, is beautiful. … Living is relatively cheap, and between the docks and the tourists there is usually some kind of job around. An old musician, laughing, said once, “It used to be if you had a minds to, you could go any place in the city and get a job on Monday morning because you ‘d be the only person around that felt like working.” [Richard Alexis – in an interview in 1955]

In the nineteenth century the city was filled with music. There were brass bands, string orchestras, amateur symphonies, and wandering street singers. Dozens of little orchestras played for the endless social gatherings in the Vieux Carre. Rougher bands played in the dance halls near the river for the longshoremen and the men off the ships. With the social life, the long summers, and the dozens of resorts there was probably more music in New Orleans than in any city in the country. The music does not seem to have been entirely distinctive. The musicians relied on standard orchestrations from the New York publishing houses. The French community carries on some of the French musical tradition, centered around its French Opera House, but unlike the bitter, resentful Acadians west of the city who rejected any non-French culture, the Vieux Carre was as much concerned with being “cultured” as it was with being simply French.

In the last years of the century and until about the time of the first World War the city was troubled with far reaching changes in social structure. Because of an influx of new families there was for several years an overcrowded tenement condition in some of the poorer Negro neighborhoods, on the upriver side of Canal Street, the Creoles of Color – French speaking mixed bloods – were included in the general restrictions of legislated segregation, and a large district near the downtown business district was opened for prostitution and gambling. Each of these factors contributed to the development of a local orchestral dance style that was to be the heart of American jazz music. …

The aim of this group of recordings – done in the city in the seven years between 1951 and 1958 – was to find and preserve as much of the cities musical tradition as possible. The music that somehow captured some of this relaxed, romantic past. Here is the music of the brass bands, the dance halls, Mardi Gras, and the music of the streets themselves. The music of shoe shine boys, vegetable criers, guitar players, and street evangelists. The music that was recorded was as much as possible the distinctive music of the city. …

Here in all it variety and glory is the music of New Orleans.

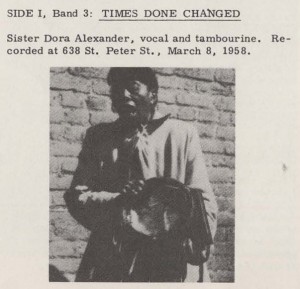

Sister Dora Alexander, a “colorful street evangelist who makes a meager living singing on the streets of Vieux Carre”, sings Times Done Changed (from Smithsonian Folkways):