For the 2012-2013 academic year, Glastonbury teacher and writer David Polochanin was awarded the James Marshall Fellowship while on sabbatical to research the archives at the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection and create young adult poetry and fiction of his own. This is the last in a series of blog installments on his insights, observations, and discoveries.

Blog post 4: On Natalie Babbitt’s Tuck Everlasting, and Some Final Thoughts On My Fellowship

“Tuck Everlasting is a fearsome and beautifully written book that can’t be put down or forgotten… I esteem it as a work or art, but it makes me as nervous as a cat. If I were twelve, on the other hand, I would love it.”

– Jean Stafford, The New Yorker, 1975

“It’s almost impossible to pick one book that speaks to all the needs, dreams, desires of children in these years of the Search for Self. But if we were to choose one book for a ten to twelve- year-old stranded on that proverbial desert island, it would probably be Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt.”

– From Choosing Books for Kids: Choosing the Right Book For the Right Child At The Right Time (Ballantine Books, 1986)

Unless you’re a researcher, author, or interested in the inner workings of the writing craft, it is likely that, when reading a new book, with its glossy cover and crisp new pages, you will never know the labor involved in writing it. That’s not what draws people toward reading literature, usually. You might read a review on amazon.com or in a newspaper. You may get a recommendation from a friend, or read a blurb on a back cover in a bookstore.

It’s also likely that few readers probably care about that process – the multiple drafts, the dead-ends, the outlines, the correspondence with agents and editors – in general, the ‘messiness’ that goes along with writing a book. After all, there are a select few who have the ambition to write a book, even fewer who pull it off, and fewer still who get their books published. Most readers, I submit, read for entertainment, not to study the writing process.

Good thing for me that I like to do that.

When examining drafts of Natalie Babbitt’s Tuck Everlasting, the 1975 masterwork of children’s literature often listed on all-time best-books-for-children lists, it became immediately clear that her process was not easy or quick. It wasn’t a masterpiece the first time around. There are three drafts included in the collection, and the first two are thoroughly edited, with numerous cross-outs, inserts, writing all over the top, side, and bottom margins, places where new paragraphs need to be inserted, arrows drawn from here to there. Whether it’s a change from “said” to “whispered”, changing a reference from a character’s name to a pronoun reference, the elimination of how a chapter would begin, the manuscript is marked up – in a good way. When I flipped through the manuscript’s first draft, not one page was left alone.

Click here for an example of Natalie Babbitt’s revision process.

One powerful example of this is at the end of Chapter 22, where Babbitt adds this dramatic, skillful ending in handwritten script in the bottom and side margins. The cross-outs are Ms. Babbitt’s.

Mae had killed the man in the yellow suit. And she had meant to kill him…

Winnie had killed a wasp once, in fear and anger, just as it in time to spare herself a stinging. She had slammed at the wasp with a heavy book, and killed it. And then, at once, seeing its body broken, the thin wings stilled, she had at once wished it were alive again. She had wept for that wasp. Was Mae weeping now for the man in the yellow suit? In spite of her wish to spare the world, did she wish he were alive again? There was no way of knowing. But Mae had done what she thought she had to do. Winnie closed her eyes to shut out the silent pulse of the lightning.

I don’t know about you, but when I see examples of revision like that – which eventually became a permanent part of the story – I get chills. To know that paragraph was not in Ms. Babbitt’s mind when initially composing the first draft speaks volumes about the importance of revising, and why writers must revise if they are to push themselves to write their best work.

Here is another deft example of Babbitt’s revision, her first draft of the opening paragraph to chapter 25, which came to be the first paragraph of Chapter 23. Again, the cross-throughs are Babbitt’s.

It was the longest day: mindlessly hot, unspeakably hot, a cruel punishment to a guiltless world for unknown too hot to move, or even think. The countryside, the village of Treegap, the wood, motionless all lay whipped and helpless gasping. The sun was a ponderous circle without edges, a roar without a sound, a blazingglare blaze so thorough consuming that even Queen Anne’s lace cast perfect, motionless shadows and remorseless that even in the Foster’s parlor, with curtains drawn, it seemed an actual tangible presence. You could not shut it out.

In her second draft, this paragraph evolved to:

It was the longest day: mindlessly hot, unspeakably hot, too hot to move or even think. The countryside, the village of Treegap, the wood – all lay defeated whipped and beaten. Nothing stirred. The sun was a ponderous circle without edges, a roar without a sound, a blazing glare so thorough and remorseless that even in the Fosters’ parlor, with curtains drawn, it seemed an actual presence.You could not shut it out.

Notice how her language tightens. The text does not become spare – Babbitt’s prose is too descriptive and rich to be spare – but words and phrases are eliminated, and the writing is better for it.

What I wonder about, as a teacher, as a writer, is this: Do student writers know this about writing? Do they know that this is a normal part of a writer’s process? That even the drafts of some of the greatest masterworks of children’s literature were not polished or complete in the first draft, or even the second draft?

Would it help for them to see this? I believe so. As a freelance writer, poet, and former journalist myself, I derived an education – and also inspiration – from reading through Babbitt’s drafts and witnessing her process.

A few other interesting things caught my attention as I read through the three drafts. First, the lead character, Winnie, was originally not named Winnie. She was Daisy. Only after chapter 10 of her second draft did Babbitt change her name. Also, the title of the book, etched in the minds of children and adults alike, was not a certain thing. During the process, Babbitt brainstormed various titles, including: The Ripe Old Age Of Always, Ancient, An Ancient Tender Age, Daisy and Forever, and Tuck Everlasting.

I wondered why these changes were made – with these and several other questions. There are sometimes limitations when reading through archival materials, so I thought the only way to get the answers was to ask Natalie Babbitt herself.

Five days after sending her a list of my questions, Ms. Babbitt graciously and generously responded. Her responses provide insights about Tuck, her personal writing process, and she even revealed what, to her, is the finest piece of children’s literature.

Here is the entire, unedited transcript of my questions and her answers. I chose not to shorten it because her responses are simply too good to edit.

1. I noticed [in your notes] that there appeared to be a list of potential titles for this book, including:

The Ripe Old Age Of Always Daisy And Forever

Ancient Tuck Everlasting

An Ancient Tender Age

How did you ultimately arrive at Tuck Everlasting? Was it your decision or an editor’s? Do you recall what you were thinking while going through this process? And, do you think the title is especially important for this book, or if the book would have succeeded had you named it something else?

I want to start by saying there are no rules for writing stories, once you get past grammar and punctuation. Everyone has systems of their own. I think choosing a title is one of the most difficult extras. But finally, for me, anyway, a title comes to the head of the list because, whether the writer knows it or not, it should say best what needs saying: it tells something about the story it represents, but not too much – and it needs to have an almost musical rhythm to it. My editor, without whom I’d never have written a word, has never demanded one title or another – he leaves it up to me – but if he dislikes the sound of a title, or its seeming meaning, he’ll say so. But I doubt if a given title would make a success of a story, good, bad, or indifferent. Leaning on any part of a story – except the story itself – to create success spells disaster.

2. I noticed in the first draft and through Chapter 10 of the second draft that the lead character was named Daisy. Can you tell me why you made the change to Winnie? Also, it looked like she was possibly named Anna in one of the drafts. Can you comment on why you changed her name and if you had changed characters’ names in other books you have written while in the process of writing?

The name of my main character in Tuck was changed a number of times because, first, I wanted a name that was popular at the time the story takes place, and second, I wanted to find a name that, for me sounded serious – not cute; a name representative (for me) of the character’s personality. “Daisy” began to annoy me. Since then, mostly, I choose names very carefully while I’m planning a story. “Winnie”, as you know now, is a nickname for “Winifred”, and both can be used here to good effect. I think.

3. About the process… did you realize you were writing something extraordinary/special as you were composing Tuck? If so, when, and how did this impact your writing?

Did I realize I was writing something extraordinary when I was writing Tuck? Not in the least. In fact, I was pretty sure the theme had already been used many times. It still surprises me that it was fairly unique. But I can tell you that many adults, when I told them what the basic theme of the story was going to be, were horrified. “Write about death for children? That’s a terrible idea! They won’t understand that! It will only scare them!” Wrong! Completely wrong! I have had wonderful, articulate letters from thoughtful, philosophizing (if that’s a word) children steadily throughout the years since it appeared. It is mainly to the credit of reading teachers that it has been used in schools, bless them. But the children understand it by themselves, and have a lot to say about it. I wish this society would stop thinking that everyone under the age of seventeen is useless and dumb.

4. I noticed that your first draft was in longhand. Is that how you typically start to write? If so, why do you feel that method works for you?

My first draft was in longhand because, in the 70s, computers were not commonplace. I wrote in longhand, and then typed it all on my typewriter, chapter by chapter, as I went along. It’s what everyone did, so far as I know.

5. Can you comment on the writing process of this book? Did the writing happen more quickly or slowly than usual? Do you recall how long it took to write the 1st draft, to finish the second draft, and complete the third?

I don’t know if I ever had a writing process exactly. I never began a story (on paper) until I knew what it was that I wanted to say, and how the story would end. I have never begun a story without knowing what the ending will be. And, as far as I’m concerned, every story should have a purpose. But you have to be really careful not to preach. Some stories come easily because their purpose is clear from the beginning. But my latest story, The Moon Over High Street, took ten years to become a real book. In the beginning, it was terrible, and I kept throwing most of it away. But I think it works all right now that it’s complete.

6. Why do you think, in this age of fickle, and sometimes odd, tastes in children’s literature, that Tuck has endured all these years? Any theories?

I think Tuck has lasted because, no matter how many years go by, the question of death, and how to live with it, never goes away. What you call ‘odd’ and ‘fickle’ about tastes in children’s literature are aspects that do not come from the young readers themselves. They come mostly from writers – and illustrators – who are trying to become established. Nothing wrong with that. But I think the best themes come from the people who remember what it was really like to be a child. My childhood is very clear and distinct to me. In fact, I think my whole philosophy was created before I was ten years old, and it has never changed. This doesn’t mean that I think my books are special in any way – after all, I started out wanting to be an illustrator – but at least they’re honest, and, I hope, direct.

7. I noticed that you had a good deal of notes and outlining, including a chronology, as part of your manuscript. Is this typical for you? If so, why do you feel that’s an important part of your process? Does it make the writing any easier?

Click here for Natalie Babbitt’s handwritten chronology for Tuck Everlasting.

Yes, I take a lot of notes and do a lot of research, and think and plan endlessly. I can’t start writing until the story has a shape and a purpose (for me) and a good ending. Not happy, necessarily, but rational and reasonable.

8. Your first two drafts include many revisions, cross-outs, arrows all over the margins, etc. As a teacher and a writer, it was excellent to see the, for lack of a better word, ‘messiness’, of this process. What is your revision process like? Do you read your work aloud? Do you have other readers you count on for feedback? It seemed that some of these revisions were revelatory and substantial. Do you expect to make significant changes when revising, or are you surprised by them?

My drafts now are a lot tidier than they used to be. Computers are a great help. But there have been lots and lots of cross-outs and arrows in my head. And that’s where the revisions try themselves out. I think about a new story endlessly, and completely stop reading anything else until there’s room in my head once again. No, I don’t read my work aloud except when I have a few beginning pages. Then, sometimes, I send a few paragraphs to my editor (his name is Michael di Capua, and we’ve been together for more than 45 years). He is very candid in his reactions, and I treasure them. But I don’t think I’ve ever read anything aloud to my husband. He’s got a PhD in American Studies, with a specialization in American literature, and that aspects usually scares me. Mostly, he reads my books when they’re published.

9. What are a few of what you believe to be the finest examples of children’s literature, all-time? A Natalie Babbitt Top 5 or Top 10?

The finest example of children’s literature is, to me, Alice in Wonderland. I read it first when I was in fourth grade and it has formed a lot of different pieces of my taste and philosophy. The language is wonderful, and Alice herself is the only character in the book that has a particle of sense. It tells the truth, and it tells it with objectivity and humor and shows again and again what adults are really about.

Click here for two versions of the dust jacket design for Tuck Everlasting, one illustrated by Natalie Babbitt.

. . .

On a closing note, back in December when I began this fellowship, when I discovered that Tuck Everlasting was in the NCLC collection, I decided that I wanted to write my final blog post about this book. That, along with Natalie Babbitt’s thoughtful and revealing responses, makes me feel as though I made the right decision. For me, anyway. There could have been any number of paths that this fellowship took; there are hundreds of boxes of material that I did not explore. But I do want to recognize and thank the NCLC curator Terri Goldich for allowing me tremendous latitude in what I did, and for her support along the way. Thanks, also, to the other curators and Dodd Center staff, including Betsy Pittman, for accommodating my requests and answering my questions. I’m going to miss this place.

This fellowship was an unexpected, yet significant part of a sabbatical in which I have mainly written young adult poetry – I have a collection of poems that I am currently pitching to agents and editors – and a collection of short stories that I am planning to polish and revise in the next few weeks. I am grateful to the Glastonbury School District, its Board of Education, Superintendent of Schools Alan Bookman, my principal at Gideon Welles School, Jay Gregorski, and the Director of Reading and Language Arts, Joanne St. Peter, for supporting this sabbatical. What an unparalleled professional development opportunity. I learned a lot about myself as a writer and a teacher and look forward to returning to the classroom in the fall.

I think it’s appropriate to finish this post with Natalie Babbitt’s last words to me in her letter, when she puts her writing process simply, perhaps deceptively so.

What it comes down to, for me, is: you have to have something to say, and you have to like words. And that’s about it.

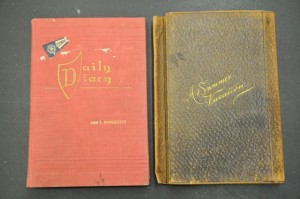

At first I viewed the diaries in the Dodd Center’s collection purely as sources. I was interested in the stories they could tell me about the past and about the people who occupied it. I was also interested in the quite literal range of forms and colors present in this collection. Some, like Ann Winchester’s are handwritten in a book printed with “Diary” on the front. Hers is bright red. Others are written in tiny notebooks, and others in leather-bound volumes. Some only include personal entries. In others, notes on the writer’s day are included alongside general musings and business records.

At first I viewed the diaries in the Dodd Center’s collection purely as sources. I was interested in the stories they could tell me about the past and about the people who occupied it. I was also interested in the quite literal range of forms and colors present in this collection. Some, like Ann Winchester’s are handwritten in a book printed with “Diary” on the front. Hers is bright red. Others are written in tiny notebooks, and others in leather-bound volumes. Some only include personal entries. In others, notes on the writer’s day are included alongside general musings and business records.