More than 2000 UConn alumni served in World War II; 114 of them lost their lives in the conflict. After the war the Veteran’s Administration requested that the university accept between 3000 and 4000 returning soldiers as students. In 1946 the campus had 792 veterans enrolled as students (11 of them were women) with another 300 at the Hartford and Waterbury extension campuses and 154 are enrolled in the Law, Insurance and Pharmacy schools. Eleven temporary barracks, nicknamed “Siberia” because of their distance from the main campus, were built on “the site of the former agronomy plots bordering the main road to Willimantic.” This site is now the Fine Arts Complex and E.O. Smith High School. As more veterans were accepted to UConn more housing was built or found in nearby Willimantic.

Can We Save the Botany Degree? Naturalist & Teale Researcher Richard Telford’s Latest Post, from Connecticut’s Trail Wood

By Richard Telford, The Ecotone Exchange, 23 October 2015 (excerpt)

On October 17, 1959, less than six months after moving to Trail Wood, the beloved private nature sanctuary where he would spend the rest of his life, American naturalist writer Edwin Way Teale wrote the following entry in his private journal:

On October 17, 1959, less than six months after moving to Trail Wood, the beloved private nature sanctuary where he would spend the rest of his life, American naturalist writer Edwin Way Teale wrote the following entry in his private journal:

We are presented with life memberships in the Baldwin Bird Club and given a fine vasculum for collecting plants. So we round out our long association with this nature group—over a period of more than 20 years. Now we ‘have other lives to live.’ We watched them go with thankfulness in our hearts that we could stay.

I first read this passage two summers ago while researching Teale’s early days at Trail Wood with the generous support of the University of Connecticut, where Teale’s papers are permanently housed in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. At the time, I was examining the extraordinary transformation that occurred in the lives of Edwin and his wife and collaborator Nellie with their move to Trail Wood, a site Edwin would subsequently declare to be “our Promised Land” (September 8, 1959). Teale chronicled this transformation in The Hampton Journal, 1959-1961, the first of four 500-page unpublished observation journals he kept at Trail Wood over a period of twenty-one years. Continue reading…

Human Rights Photographer’s Collection Donated to UConn

by Suzanne Zack, University Libraries, for UConn Today

The late U. Roberto (Robin) Romano was an accomplished photographer, award-winning filmmaker, and human rights advocate who unflinchingly focused his eye and lens on children around the world, capturing the violation of their rights.

The late U. Roberto (Robin) Romano was an accomplished photographer, award-winning filmmaker, and human rights advocate who unflinchingly focused his eye and lens on children around the world, capturing the violation of their rights.

Since 2009, Romano had made a limited number of his images available to researchers through the UConn Libraries’ Archives & Special Collections. Now, two years after his death, his total body of work, including video tape masters and digital video files, hundreds of interviews, thousands of digital photos and prints, plus his research files have been given to UConn and will now be available to those who examine human rights issues.

More than 100 of Romano’s images of child labor originally exhibited at the UConn’s William Benton Museum of Fine Art in 2006 are available online from the University Archives & Special Collections. These are the first of the more than 130,000 still images that will be available online for research and educational use once the collection is processed. The Archives & Special Collections plans to digitize the entire collection of analog still images, negatives, and research files, creating an unprecedented online resource relating to documentary journalism, child labor and human rights, and other social issues that Romano documented during his lifetime. Continue reading…

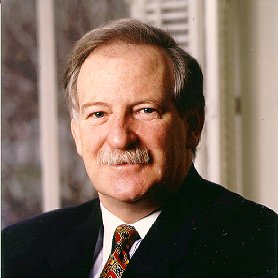

Bill Clinton back on campus to accept the Dodd Prize

President Bill Clinton came to the University of Connecticut in 1995 to dedicate the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. He returns today, exactly twenty years later, to receive the Thomas J. Dodd Prize in International Justice and Human Rights, along with the international Human Rights Education organization Tostan. We’re delighted to welcome him back to UConn! Here he is at the ceremony on October 15, 1995.

Leap Before You Look @ICAinBoston: National Exhibition of Black Mountain College Arts and Artists

The teachers and students at Black Mountain College came to North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains from around the United States and the world. Some stayed for years, others mere weeks. …They experimented with new ways of teaching and learning; they encouraged discussion and free inquiry; they felt that form in art had meaning; they were committed to the rigor of the studio and the laboratory; … They had faith in learning through experience and doing; they trusted in the new while remaining committed to ideas from the past; and they valued the idiosyncratic nature of the individual. But most of all, they believed in art, in its ability to expand one’s internal horizons, and in art as a way of living and being in the world.

The teachers and students at Black Mountain College came to North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains from around the United States and the world. Some stayed for years, others mere weeks. …They experimented with new ways of teaching and learning; they encouraged discussion and free inquiry; they felt that form in art had meaning; they were committed to the rigor of the studio and the laboratory; … They had faith in learning through experience and doing; they trusted in the new while remaining committed to ideas from the past; and they valued the idiosyncratic nature of the individual. But most of all, they believed in art, in its ability to expand one’s internal horizons, and in art as a way of living and being in the world.

Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957 is the first comprehensive museum exhibition on the subject of Black Mountain College to take place in the United States. Featuring works by more than ninety artists, from painting and sculpture to photography and ceramics, the exhibition will be accompanied by a robust program of music, dance, performance, lectures, and educational programs. The exhibition had its premiere on Saturday at the ICA/Boston and will be on view from October 10, 2015 to January 24, 2016.

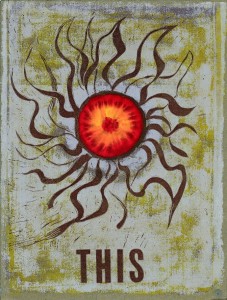

Archives and Special Collections is thrilled to be a part of the exhibition, where items from the literary collections are on display together with works loaned from archives and museums throughout the United States and Europe. Items on loan from Archives and Special Collections include a painting by poet and artist Fielding Dawson titled “Cy Twombly.” Dawson, whose papers reside here in the archives, was a student at Black Mountain College in the early 1950s along with fellow students Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, and Dan Rice. Rare documents, manuscripts and “This” (pictured) a poetry broadside by Charles Olson printed at Black Mountain College are also on view in the exhibition. Charles Olson’s archive of manuscripts, letters, diaries, photographs and books resides here at the Dodd Research Center. A rich document of the poet’s life and work, the archive includes a variety of materials from his time at Black Mountain College where he began teaching in 1948 and assumed the role of rector (formally) in 1954. Olson’s poetics were very much influenced by the artists, faculty, students and atmosphere of experimentation that he encountered at Black Mountain College, and that in turn influenced a generation of writers that were later associated with, according to the New American Poetry editor Donald Allen, the “Black Mountain School.”

Organized by Helen Molesworth, the ICA’s former Barbara Lee Chief Curator, with ICA Assistant Curator Ruth Erickson, the exhibition argues that Black Mountain College was an important historical precedent, prompting renewed, critical attention to relationships between art, democracy, and globalism. The college’s influence, and its critical role in shaping many major concepts, movements, and forms in postwar art and education, can still be seen and felt today.

1966: Collections from 50 Years Ago on Display

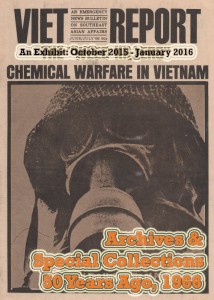

At the Archives & Special Collections, we have been ramping up our interoperability. What does that mean exactly? Twinkling screens, chatter of audio recording and tactile interactions with materials on exhibition. Currently, we are featuring collection materials from 50 years ago in the archives to help highlight the year 1966. These selections contain personal correspondence and work from famous artists and activists like Ed Sanders, Allen Ginsberg, Diane Di Prima and Abbie Hoffman. Popular culture and ephemera from comic books to Life magazine relating to the politics of War in Vietnam, LSD, the rise of Black Power and the battle against Communism.

At the Archives & Special Collections, we have been ramping up our interoperability. What does that mean exactly? Twinkling screens, chatter of audio recording and tactile interactions with materials on exhibition. Currently, we are featuring collection materials from 50 years ago in the archives to help highlight the year 1966. These selections contain personal correspondence and work from famous artists and activists like Ed Sanders, Allen Ginsberg, Diane Di Prima and Abbie Hoffman. Popular culture and ephemera from comic books to Life magazine relating to the politics of War in Vietnam, LSD, the rise of Black Power and the battle against Communism.

Included in the exhibit are Alternative Press Collection materials documenting the War in Vietnam ranging from the scholarly to the ephemeral. The Poras Collection of Vietnam War Memorabilia contains posters, death cards, publications and satirical army culture objects demonstrating the antagonisms of war at home and abroad. From a personal collection of Navy Corpsman Cal Robertson, his correspondence from Vietnam in 1966 while deployed over two tours as a medic attached to a marine platoon, detailing the daily grind and uncertainties of waiting in the jungle and relaying safety concerns to loved ones back home. The Alternative Press also includes a trove of anti-war publications such as the Committee for Nonviolent Action.

The physical exhibit in our reading room is but one element of our program to promote access to collections through outreach. Media displays within the Archives Reading Room featuring additional photographs and videos demonstrate the interactive qualities of physical objects outside of a static display. Currently, the newest arrival to the reading room is a large tablet-like touch table which has digital content loaded from our Omeka exhibit on1966 which will be unveiled in the coming month on the web.

The physical exhibit in our reading room is but one element of our program to promote access to collections through outreach. Media displays within the Archives Reading Room featuring additional photographs and videos demonstrate the interactive qualities of physical objects outside of a static display. Currently, the newest arrival to the reading room is a large tablet-like touch table which has digital content loaded from our Omeka exhibit on1966 which will be unveiled in the coming month on the web.

For more information, follow us @UConnArchives on twitter and facebook where we promote exhibits like this one and events happening around the Archives.

promote exhibits like this one and events happening around the Archives.

Esphyr Slobodkina – Modernist (Children’s Book) Illustrator/Author

by JoAnn Conrad, Recipient of the 2015 Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant

Part of my ongoing research into children’s picturebooks of the mid-twentieth century has to do with the ways in which the work of illustrators has insinuated itself into the public memory even as the names of individual artists may be relatively obscure. This is the case with the rare female artist and, particularly, Esphyr Slobodkina, as her influence is inversely proportional to the obscurity of her name. “Esphyr Slobodkina . . .helped pave the way for the acceptance of abstract art in the United States and translate[d] European modernism into an American idiom.”[1]

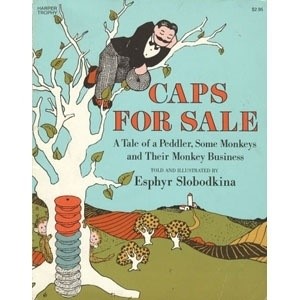

A simple and serendipitous anecdote demonstrates this: While researching her papers at UConn’s Archives and Special Collections this summer, I was living across the street from the UConn Bookstore. One day, I noticed a display in the window announcing “Caps for Sale” [Fig. 1], clearly alluding to one of Slobodkina’s most popular books of the same name [Fig. 2]. The power of the sale poster derives from and depends on the reference to the book, which is assumed to be automatic.

There is a fair amount about Slobodkina’s life and work available. The Finding Aid for the Slobodkina Papers at Archives and Special Collections provides a brief biography as does the website of the Esphyr Slobodkina Foundation. The 2009 Rediscovering Slobodkina: A Pioneer of American Abstraction includes information on her life as well as her contributions to the art world, but the full biography has yet to be written. Esphyr Slobodkina anticipated that it would be written, however, and drafted a comprehensive, detailed, 5-volume manuscript “Notes for a Biographer” which resides in her papers. The Slobodkina Papers contain much more than is in her books – things that would never be published but which give a researcher like me access to insights into the thoughts and motivations of the artist. One of the pleasures of this kind of archival research is not only this intimate and personal connection one makes across time, but also the unexpected revelations into the personality of the artist that informs her work. My intention here is to provide some of those “off the books” glimpses into the work and person – Esphyr Slobodkina.

Esphyr Slobodkina was born to a wealthy Russian-Jewish family in Russia before the Revolution. Continue reading…

Esphyr Slobodkina – Modernist (Children’s Book) Illustrator/Author

by JoAnn Conrad

Part of my ongoing research into children’s picturebooks of the mid-twentieth century has to do with the ways in which the work of illustrators has insinuated itself into the public memory even as the names of individual artists may be relatively obscure. This is the case with the rare female artist and, particularly, Esphyr Slobodkina, as her influence is inversely proportional to the obscurity of her name. “Esphyr Slobodkina . . .helped pave the way for the acceptance of abstract art in the United States and translate[d] European modernism into an American idiom.”[1]

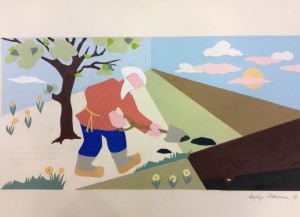

A simple and serendipitous anecdote demonstrates this: While researching her papers at UConn’s Archives and Special Collections this summer, I was living across the street from the UConn Bookstore. One day, I noticed a display in the window announcing “Caps for Sale” [Fig. 1], clearly alluding to one of Slobodkina’s most popular books of the same name [Fig. 2]. The power of the sale poster derives from and depends on the reference to the book, which is assumed to be automatic.

There is a fair amount about Slobodkina’s life and work available. The Finding Aid for the Slobodkina Papers at Archives and Special Collections provides a brief biography as does the website of the Esphyr Slobodkina Foundation. The 2009 Rediscovering Slobodkina: A Pioneer of American Abstraction includes information on her life as well as her contributions to the art world, but the full biography has yet to be written. Esphyr Slobodkina anticipated that it would be written, however, and drafted a comprehensive, detailed, 5-volume manuscript “Notes for a Biographer” which resides in her papers. The Slobodkina Papers contain much more than is in her books – things that would never be published but which give a researcher like me access to insights into the thoughts and motivations of the artist. One of the pleasures of this kind of archival research is not only this intimate and personal connection one makes across time, but also the unexpected revelations into the personality of the artist that informs her work. My intention here is to provide some of those “off the books” glimpses into the work and person – Esphyr Slobodkina.

Esphyr Slobodkina was born to a wealthy Russian-Jewish family in Russia before the Revolution. After the Revolution and her  family’s

family’s  change in fortune and status, they moved east, to Harbin, and then, via Vladivostok, to the United States. The readjustment to their diminished financial situation was the beginning of her fashion design career – helping her mother sew dresses for clients in Harbin. Throughout her life, Esphyr (whose friends called her Phyra) would sew and consult on fashion and home décor to supplement her income, just as she did with children’s books (in amongst her papers in Box 13 are two experimental fabric children’s books; an attempt at combining her two skills). Slobodkina kept scrapbooks, using large binders of wallpaper samples as her medium. Here, along with dummies for greeting cards, sketches, reviews, letters from children thanking her for her books, fashion design [Fig. 3], the peddler from Caps for Sale interacts with Slobodkina’s “poodies” from her very first children’s book attempt – Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 4]. In these scrapbooks, then, Slobodkina’s various artistic and commercial endeavors combine and interact. Unlike her biographers, perhaps, she did not segregate her work into compartments.

change in fortune and status, they moved east, to Harbin, and then, via Vladivostok, to the United States. The readjustment to their diminished financial situation was the beginning of her fashion design career – helping her mother sew dresses for clients in Harbin. Throughout her life, Esphyr (whose friends called her Phyra) would sew and consult on fashion and home décor to supplement her income, just as she did with children’s books (in amongst her papers in Box 13 are two experimental fabric children’s books; an attempt at combining her two skills). Slobodkina kept scrapbooks, using large binders of wallpaper samples as her medium. Here, along with dummies for greeting cards, sketches, reviews, letters from children thanking her for her books, fashion design [Fig. 3], the peddler from Caps for Sale interacts with Slobodkina’s “poodies” from her very first children’s book attempt – Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 4]. In these scrapbooks, then, Slobodkina’s various artistic and commercial endeavors combine and interact. Unlike her biographers, perhaps, she did not segregate her work into compartments.

After arriving in the US in 1929, Esphyr became one of the founding members of the American Abstract Artists Association, and worked on various WPA projects during the Depression (including many murals in the New York City area). But in 1937, as the Artists’ Union was disintegrating and the New Deal was succeeding, those WPA jobs became more scarce. Phyra again turned to the industrial arts – as a fabric print designer at the Arrow Printing Co. in Patterson, NJ, under the name Phyra Nay.

While still in Russia during those turbulent days, Phyra was not only tutored in art, but was also exposed to the work of the avant-garde that so dominated the art scene of the 1910s and 1920s in Russia: “I liked the early Russians, the Constructivists. And there were some very good women artists – Nathalia [sic] Goncharova. And there were of course decorative Russian artists. I happen not to sneeze at the decorative artists either.” And from another passage about living in Harbin:

We didn’t hear everything but some things reached us . . . There was a great big exhibit of Cubist art in Ufa . . . the next town from the town where I was born [Chelyabinsk]. That was the Cubists of the Italian type, Futurism, and it was all in those primary colors, broken up colors, purple and green . . . and all the nudes were triangles and squares and all broken up like spectral colors. That was as far as we got and we went and we stared and of course we understood nothing, but everyone laughed and said that was modern art [Interview transcript March 23, 1991, in Box 4, Esphyr Slobodkina Papers].

Later, living in the US in the 1930s she describes other influences: “We were into the German Expressionists, with a dash of [Oskar] Kokoschka and [Chaim] Soutin[e] here and there”(Box 1, Esphyr Slobodkina Papers, MSS pg. 517). [2] The avant-garde was to be a major influence in her artistic career as she deepened her interest in abstract art and that most deconstructive of techniques – collage. Here again, Slobodkina was able to translate the techniques of the avant-garde into the “decorative” or public arts, and in the process normalizing an avant-garde aesthetic in the popular imagination. In her collaboration with the great children’s book author Margaret Wise Brown, first with The Little Fireman (1938), then with The Little Farmer (1948) and The Little Cowboy (1948), Slobodkina introduced collage into children’s picturebooks. Barbara Bader would later refer to this pioneering picturebook as “perhaps the apogee of modernism in the picture book.”[3] Slobodkina’s published children’s picturebooks featuring collage are readily available, but in the collection in Archives and Special Collections there are four large collages for an unpublished story “The Turnip that Grew” which she refers to as a “Russian Folktale” (the manuscript for the story is in Box 2, the pictures are framed but are also part of the collection) [Fig. 5].

Later, living in the US in the 1930s she describes other influences: “We were into the German Expressionists, with a dash of [Oskar] Kokoschka and [Chaim] Soutin[e] here and there”(Box 1, Esphyr Slobodkina Papers, MSS pg. 517). [2] The avant-garde was to be a major influence in her artistic career as she deepened her interest in abstract art and that most deconstructive of techniques – collage. Here again, Slobodkina was able to translate the techniques of the avant-garde into the “decorative” or public arts, and in the process normalizing an avant-garde aesthetic in the popular imagination. In her collaboration with the great children’s book author Margaret Wise Brown, first with The Little Fireman (1938), then with The Little Farmer (1948) and The Little Cowboy (1948), Slobodkina introduced collage into children’s picturebooks. Barbara Bader would later refer to this pioneering picturebook as “perhaps the apogee of modernism in the picture book.”[3] Slobodkina’s published children’s picturebooks featuring collage are readily available, but in the collection in Archives and Special Collections there are four large collages for an unpublished story “The Turnip that Grew” which she refers to as a “Russian Folktale” (the manuscript for the story is in Box 2, the pictures are framed but are also part of the collection) [Fig. 5].

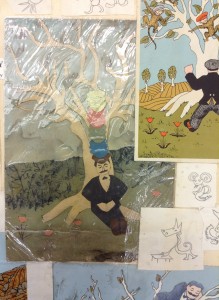

Collage was also the basis for the illustrations of Caps for Sale and the one of the original collages is  pasted in the aforementioned scrapbook [Fig. 6]. Preserved under plastic wrap, the image not only makes emphatic the link between handiwork and art, but also is penetrated by the impish Poodies. Slobodkina, in an interview, relates that the inspiration for the book came from a story she heard being told by the teacher of her sister-in-law’s child, and because of this ambiguous authorship, that William Scott had been hesitant to publish it. On the advice of Bertha Mahoney (of The Horn Book), Esphyr gave the peddler a name, and developed the plot more, whereby it was published by Harper Collins (1940) under the editorship of Ursula Nordstrom, and then later by Scott.

pasted in the aforementioned scrapbook [Fig. 6]. Preserved under plastic wrap, the image not only makes emphatic the link between handiwork and art, but also is penetrated by the impish Poodies. Slobodkina, in an interview, relates that the inspiration for the book came from a story she heard being told by the teacher of her sister-in-law’s child, and because of this ambiguous authorship, that William Scott had been hesitant to publish it. On the advice of Bertha Mahoney (of The Horn Book), Esphyr gave the peddler a name, and developed the plot more, whereby it was published by Harper Collins (1940) under the editorship of Ursula Nordstrom, and then later by Scott.

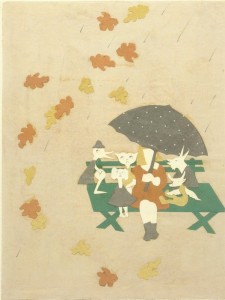

I want to close this insider’s look into the Slobodkina papers with the one item that is not  only my favorite, but which shows how funny, creative, and engaging Phyra was. It again is related to Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 7], an unpublished children’s book that served as Esphyr’s introduction to Margaret Wise Brown and Wm. Scott Publishers. The book was not an ideological fit with the Bank Street “Here-and-Now” pedagogues because it featured the whimsical imaginary creatures – the eponymous Poodies.[4] But the art work and use of collage attracted their attention and eventuated in the collaborative work between MWB and Slobodkina that began with The Little Fireman. In the Slobodkina Papers, however, was a small “promotional” sheet that she’d worked up for Mary and the Poodies, a kind of contest for kids to name the Poodies. To the first to respond awaits either a Bachelors or a Masters of Poodology, conferred by Prof. Amoritus Maximus!

only my favorite, but which shows how funny, creative, and engaging Phyra was. It again is related to Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 7], an unpublished children’s book that served as Esphyr’s introduction to Margaret Wise Brown and Wm. Scott Publishers. The book was not an ideological fit with the Bank Street “Here-and-Now” pedagogues because it featured the whimsical imaginary creatures – the eponymous Poodies.[4] But the art work and use of collage attracted their attention and eventuated in the collaborative work between MWB and Slobodkina that began with The Little Fireman. In the Slobodkina Papers, however, was a small “promotional” sheet that she’d worked up for Mary and the Poodies, a kind of contest for kids to name the Poodies. To the first to respond awaits either a Bachelors or a Masters of Poodology, conferred by Prof. Amoritus Maximus!

JoAnn Conrad is a professor of Anthropology and Folklore at California State University, East Bay (Hayward). Her current research focuses on the impact of immigrant artists on the American cultural landscape in the post-WWII period, particularly in their role as illustrators of children’s picture books. Conrad feels that these immigrant artists, through their work in such quotidian, mass-produced materials as children’s books, magazines, and even film and animation, were important translators of a modernist aesthetic into the day-to-day lives and sensibilities of millions for whom the art world was a distant and foreign sphere. Conrad has researched such artists as Feodor Rojankovsky, Tibor Gergely, and Gustaf Tenggren. In Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, she was specifically researching Esphyr Slobodkina and Leonard Weisgard (not an immigrant to the US, but influenced by European modernism). Conrad is the recipient of the 2015 Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant.

Sources cited:

All archival material referenced is from the Esphyr Slobodkina Papers. Archives & Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

[1] Slobodkina, Esphyr, and Sandra Kraskin. Rediscovering Slobodkina: A Pioneer of American Abstraction : [ Catalog of an Exhibition Held at the Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, Ny … between Jan. 10, 2009 and Apr. 18, 2010]. Manchester, Vt: Hudson Hills Press, 2009. Print.

[2] In an email correspondence with John Bowlt, dated Aug. 6, 2015, he indicates that David Burliuk, the so-called “Father of Russian Futurism”, held a one-man show in Ufa in 1916.

[3] Barbara Bader, “A Lien on the World.” (New York Times Book Review, November 9, 1980): 66.

[4] For more on the collaborative work of Margaret Wise Brown and Esphyr Slobodkina, see Leonard Marcus, “Modernist At Story Hour: Esphyr Slobodkina and the Art of the Picture Book” (http://www.slobodkinafoundation.org/books-illustrations/essay-by-leonard-marcus/).

Reflections on Archival Silences: Wrapping Up A Summer in the Stacks

by Nick Hurley, Graduate Student Intern, Summer 2015

For my final blog post of my summer internship, I want to touch on something that’s been nagging at me ever since I began my work.

For my final blog post of my summer internship, I want to touch on something that’s been nagging at me ever since I began my work.

In his book Silencing the Past, anthropologist and historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot talks about reading “silences” in the archives. According to Trouillot, honest scholars try to tell their stories as accurately as possible from the records available to them. Many times, however, these records are incomplete, as conscious choices were made by those who collected them regarding what to preserve, what to discard, and what to highlight. Thus, what is not present in an archive may at times be just as important as what is.

A cursory examination of the Bruce Morrison Papers will give any researcher an excellent overview of Morrison’s professional career. There is ample material documenting his time as an immigration lawyer, a U.S. Congressman, and a candidate for governor. But what isn’t there, or is barely there, is equally significant. Aside from being a lawyer, politician, and activist, Morrison was also a husband and father, who enjoyed playing tennis and had a profound interest in science. Where is that man?

Morrison, a former Congressman from Connecticut who served from 1983-1991, served as Chairman of the House Immigration subcommittee and authored the Immigration Act of 1990. After an unsuccessful campaign for Governor of Connecticut in 1990, Morrison became heavily involved in the quest for peace in Northern Ireland and was instrumental in paving the way for the eventual IRA ceasefires in 1994 and 1997. During this time he also served as the director of the Federal Housing Finance Board and as a commissioner on the Commission for Immigration Reform (1992-1997).

We have no way of knowing how many “filters” the papers went through before they arrived at the Dodd Research Center. Morrison’s assistants, secretaries, and Morrison himself all could have gone through and arranged files or removed documents deemed too personal or irrelevant. It should be remembered that this collection is designed to provide researchers with information on Morrison’s career as a politician, activist, and lawyer. It is not a  diary, nor does it pretend to be. Are the Morrison Papers an example of a collection that has been “silenced”? Perhaps—to a certain extent. However, a closer look at the Morrison Papers yields more personal insights than we might expect. Where do we see Morrison the man? The human being?

diary, nor does it pretend to be. Are the Morrison Papers an example of a collection that has been “silenced”? Perhaps—to a certain extent. However, a closer look at the Morrison Papers yields more personal insights than we might expect. Where do we see Morrison the man? The human being?

We can see it in the letters received—and promptly replied to—from ordinary people, many of them underprivileged, immigrants, or both, seeking legal advice or assistance from Morrison. No matter what the issue, how busy he was, or the extent to which he could help them, he always made it a point to send a reply, or to forward the letter to a colleague that could better address the issue.

We can see it in the weekly calendars filled out by Morrison’s assistants during the height of his political career, or in the midst of his run for governor. Weekdays and weekends, morning and night, he was constantly on the move, but somehow managed to find time for the occasional game of tennis, or a short weekend getaway with his wife and son.

We can see it in the heartfelt and handwritten letter sent to Irish PM Bertie Ahern following the death of his mother in 1998.

We can see it in the time stamps on his faxes; so many are after 10pm or later. Clearly, Morrison was not a “9 to 5” type of guy.

And so within volumes of seemingly routine correspondence, news clippings, and research papers contained in this collection, we can get a sense of Morrison the professional and Morrison the man. The overall impression I get is of a man incredibly dedicated to his work, but, like so many of us, equally dedicated to maintaining a home-work balance. Despite his hectic schedule, he seemed to always have time for those who needed him, whether it was his family or an underprivileged immigrant with nowhere else to turn.

Scholars, researchers, and anyone else seeking to consult an archive would do well to remember the lesson here. When a collection seems “tapped out”, dig a little deeper, or come at it from a different angle. There is always something new that can be gleaned from its pages.

It’s been a real pleasure to work on the Bruce Morrison Papers and in Archives and Special Collections this summer. I’ve enjoyed my first taste of archival work, and I’m coming away from the experience with a far better understanding of what goes into arranging the collections that we as researchers utilize for our various projects. I hope those who utilize the Morrison Papers from this point forward will find it a bit more user-friendly and informative, thanks to my efforts. It is an excellent resource, and one that we are proud to have here at the University of Connecticut!

Archives At Your Fingertips: Teaching with Archives and Special Collections | Archives & Special Collections

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources. Continue reading

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources. Continue reading

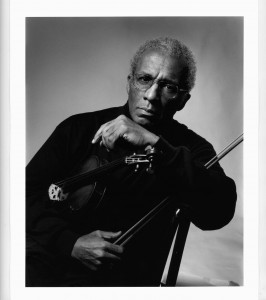

Black Experience in the Arts: Rare Sound Recordings Now Available

I grew up in Brooklyn on a diet of the public schools and the Brooklyn Dodgers, spending probably as much time in Ebbetts Field as anybody else did during that period. I am a violinist. That’s unusual, I suppose, for two reasons: one, because there are not a lot of violinists in this world, and there are even fewer black violinists. It leaves one feeling a bit like a rare bird. I must admit I didn’t think terribly much about that when I started playing the violin. I suppose if I had, I probably wouldn’t have done it.

On October 29, 1974, Sanford Allen, one of the first African American musicians to play with a major symphony orchestra and the only African American in the New York Philharmonic since 1964, spoke to a rapt audience at the University of Connecticut. The recording of his lecture, interview and performance is being preserved and made available digitally by Archives and Special Collections. The sound recordings are part of a large archive that document a groundbreaking course and performance series led by faculty of the Music Department, Edward O’Connor and Hale Smith, and the Center for Black Studies, entitled Black Experience in the Arts.

On October 29, 1974, Sanford Allen, one of the first African American musicians to play with a major symphony orchestra and the only African American in the New York Philharmonic since 1964, spoke to a rapt audience at the University of Connecticut. The recording of his lecture, interview and performance is being preserved and made available digitally by Archives and Special Collections. The sound recordings are part of a large archive that document a groundbreaking course and performance series led by faculty of the Music Department, Edward O’Connor and Hale Smith, and the Center for Black Studies, entitled Black Experience in the Arts.

Between 1970 and 1990, hundreds of African American artists, actors, musicians, composers, TV producers, dancers, opera singers, poets, historians, critics, and journalists visited UConn at the invitation of Edward O’Connor and Hale Smith. Smith, a performer and arranger who had worked with jazz greats such as Dizzy Gillespie, Chico Hamilton and the pianist Ahmad Jamal, joined the UConn faculty in 1970. Originally supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation, Black Experience in the Arts brought Orde Coombs, Conrad Buckner, Stanley Crouch, Edythe Jason, Louise Meriwether, Frederick Tillis, Oscar Walters, Jayne Cortez, Raul Abdul and others to the University, sometimes for repeat visits over the course of their careers.

Stay tuned as we continue to preserve and to make these valuable recordings more widely known and available at archives.lib.uconn.edu

Questions Are Asked [Series: 70 Years After Nuremberg] | Human Rights Archives

As summer drew to a close, work commenced in earnest in Nürnberg. Tom Dodd took on the responsibility of questioning Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Franz von Papen, and Dr. Arthur Seyss-Inquart. Formal questioning began on August 28th with Keitel. Writing to his wife Grace, Dodd described Keitel as a gentle, polite, very proper man, and wrote, “Sometimes I find myself liking him- and feeling sorry for him. He is a very bright man—in my opinion—and a very charming one too” [p.111, 8/30/1945].

The darker side of Keitel came out questioning on September 1st, 1945, when he admitted to the slaughtering of innocent men, women, and children hostages, but only after devastating attacks against the Germans [p.116,9/1/45]. Several days earlier (8/29), Dodd had caught Keitel in a lie; Continue reading...