These Connecticut Agricultural College students from 1905 seem to have enjoyed their blacksmith class. Perhaps we can petition to get this back on the curriculum?

These Connecticut Agricultural College students from 1905 seem to have enjoyed their blacksmith class. Perhaps we can petition to get this back on the curriculum?

UConn Library

Archives and Special Collections Blog

UConn Library

Archives and Special Collections BlogFollow the events and individuals of the trials in Nuremberg from its establishment in the summer of 1945 through the delivery of verdicts in October 1946, illustrated with documents and images from the papers of Thomas J. Dodd, executive trial counsel for the U.S. The blog series will also include posts from multiple guests—recognized scholars commenting on the impact, significance and present day results of the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg).

With the establishment of the International Military Tribunal (IMT) to be held in Nürnberg, Germany, the real work of creating an appropriate space for the court and the necessary supporting operations began. Thomas J. Dodd, a Connecticut lawyer on the staff of the FBI, was selected by Justice Robert Jackson, the lead prosecutor for the United States, to participate in the herculean task of collecting and sorting through the available documentation to begin formulating the U.S. team’s legal plan for the upcoming trial. Arriving in London in late July 1945, Dodd began gathering information. Writing to his wife, Dodd recounts the devastation of London as a result of bombing and his travels to some of the more well-known sights before moving on to Paris in early August following the finalization of the British, French and Soviet legal teams. Continue reading…

At 5:00pm (EST) today, tune in to WHUS Radio 91.7 FM to hear music produced and recorded by poet, novelist, and renowned scholar of the blues, jazz, and musical culture of the African diaspora Samuel Charters. Featuring our own Kristin Eshelman, Archivist for The Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture at the University of Connecticut in Archives and Special Collections, the much-anticipated radio program is a tribute to the friendship, life and legacy of Samuel Charters. Samuel Charters died in March of this year at the age of 85.

At 5:00pm (EST) today, tune in to WHUS Radio 91.7 FM to hear music produced and recorded by poet, novelist, and renowned scholar of the blues, jazz, and musical culture of the African diaspora Samuel Charters. Featuring our own Kristin Eshelman, Archivist for The Samuel and Ann Charters Archives of Blues and Vernacular African American Musical Culture at the University of Connecticut in Archives and Special Collections, the much-anticipated radio program is a tribute to the friendship, life and legacy of Samuel Charters. Samuel Charters died in March of this year at the age of 85.

Walking A Blues Road is a radio program engineered by Ken Best at WHUS, UConn’s Sound Alternative. The playlist can be tracked here for this special program.

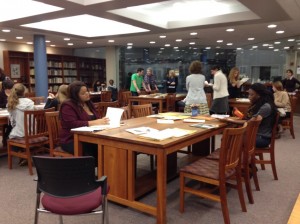

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources.

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources.

Students are encouraged to drop in for their class project, First Year Experience credit, or simply for their own personal enrichment.

Faculty, teaching assistants, and other instructors are invited to design and schedule an instruction session with staff archivists as early as possible in the academic semester. For examples of class sessions taught recently by staff archivists, see the list outlined below.

The collections offer ample source materials for interdisciplinary research and instruction in such fields as art history; nineteenth and twentieth century American history, social movements, music, literature and book arts; blues music and African American musical culture; Latin American history and culture; children’s literature and illustration; nursing history; human rights; and Connecticut history.

The repository’s collection of personal papers animate the experiences, activities and creative processes of writers, activists, artists, political figures, and UConn faculty and students through time, and are critical for studying the communities and networks in which these individuals worked and thrived.

Popular with students, the Alternative Press Collection, graphic novels, artists books, Comix, Fanzines, science fiction, Socialist/Communist Pamphlets, and other special collections offer a variety of materials for exploring diverse discourses in and across contemporary events and social issues. Publications and ephemera from non-mainstream political movements (Communism, Socialism, Anarchism, and other Radical Politics), Black Power and non-white activism and social justice organizations, Women’s Liberation/Feminist movements, presses and organizations, and Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer organizations and movements can be found in the Alternative Press Collection.

Classes that visited Archives and Special Collections for an instruction session last year include the following:

Advanced Photography

African American Experience in the Arts

American Landscapes, Walden and Thoreau

Art of China

British Literature: The Tudors

Children’s Literature

Communication Design

Connecticut Soldiers and the Civil War

The Historian’s Craft

History of Women and Gender in the United States

Introduction to Creative Writing

Irish History

Little Magazines and the Mimeo Revolution

Mexico and Nineteenth-Century Travel Narratives

The Literature(s) of Medieval Iberia

Spanish Literature and Film

Trauma and History

United States and Human Rights

Word and Image: Early Illustrated Books

If you are a faculty member, visit Archives and Special Collections during public hours, Monday through Friday, 9:00am to 4:00pm. Or contact the archives staff today to discuss a prospective viewing of materials, instruction session or class visit. We look forward to hearing from you!

Graduate intern Nick Hurley updates his progress in the Bruce Morrison Papers–

It has been a while since my introductory blog post, and much has happened between then and now! I have examined and rearranged two series of the Morrison Papers (about seven boxes of material) and prepped them for digitization, and also prepared new finding aids for each.

Series VII deals with Morrison’s time on the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform (1993-1997). It is a small collection—only two boxes—but had an interesting mix of correspondence, press clippings, and copies of government documents to look through, and was a good way to ease into my new job at the archives.

Series VIII was far more complex. It deals exclusively with Morrison’s involvement in Irish affairs. Among the five subseries I established in the new finding aid, researchers will now have access to information about topics such as Morrison’s leadership of Americans for a New Irish Agenda (ANIA) and Irish Americans for Clinton-Gore, his work on Irish immigration, and his role in urging President Clinton to take a more active role in the peace process in Northern Ireland.

It’s clear from looking through these papers that Bruce Morrison was a man incredibly committed to his work. His involvement in the Irish peace process, for example, seems manageable until you realize that while he was leading fact-finding missions to Northern Ireland and petitioning the White House for a new Irish agenda, he was also serving on the Commission on Immigration Reform (1993-1997), practicing as an immigration lawyer in New Haven, and chairing the Federal Housing Finance Board (1995-2000). He also had a wife and young son (born 1992) at home.

It’s also clear that Ireland played a huge role in much of his career. In the 1990s, he became a veritable superstar amongst the Irish-American population, due in large part to his authorship of the Immigration Act of 1990. A provision of that bill, known as the “Morrison program”, allotted more than 16,000 visas to immigrants from Ireland and Northern Ireland attempting to enter the United States. For much of the early 1990s, Morrison was a guest of honor at countless social functions at Irish clubs and institutions, and was even named one of Irish America magazine’s Top 100 Irish-Americans.

Here’s what really surprised me, however; Morrison’s upbringing and personal life don’t at all reflect his high standing in the Irish-American community, or the deep interest in all things Ireland that came to define his political career. Adopted as a baby, his Irish roots consist of a biological father who was, in Morrison’s words, “somewhat Irish.” He was raised Lutheran, not Catholic. One reporter offered the following description in a March 1997 article for the Hartford Courant:

No Irish flag waves from his porch on St. Patrick’s Day. He isn’t much of a storyteller, doesn’t quote from W. B. Yeats, and doesn’t sing Irish songs, or even profess to know any of the words. In his home, the paintings and sculptures reveal a preference for primitive art from Africa and South America. Only some expensive Irish crystal ware — gifts and awards from groups in both Ireland and America — offer any clues that Morrison has an Irish connection.

It was clear from my examination of these collections that Morrison was never destined, by virtue of his childhood experiences or family background, for the career he ended up having. So I had to ask; why Ireland? The simple answer is that as a young Congressman, spurred on by reports of human rights abuses in Northern Ireland, he was persuaded to leave the Friends of Ireland, which consisted of politicians who rarely criticized the British and limited their activities to what Morrison called “St. Patrick’s Day blather,” and join instead the Ad Hoc Committee for Irish Affairs, a more “radical” element of Congress which took a deep interest in the Ireland issue.

Even once on the committee, however, his involvement in Ireland was characterized by a certain sense of emotional detachment. In the March 1997 article, Morrison pointed to a “radicalizing experience” in 1987 that began to reverse that trend. While on a fact-finding mission to Northern Ireland, Morrison’s car was stopped by a Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC, a British-backed police force) armored vehicle:

A dozen officers surrounded the car. When he was asked for papers, Morrison handed over his passport, stamped with “Member of Congress.” The policeman refused to return it, and a shouting match ensued, with congressman and officer pulling on the passport. Other officers rifled through the trunk.

Infuriated but ever the lawyer, Morrison pulled out a notepad and began to write down police badge numbers. An RUC officer grabbed the pad. It was a crime, he said, to collect information about security forces. They were released 30 minutes later.

All that would follow—the peace process, the Morrison visas, and the outpouring of support from the Irish community—would now be more than just a political agenda for Morrison. The man himself perhaps said it best:

“Here I had this fortuitous coming together of opportunities that had made me a hero in Irish America and in Ireland . . . and it was like, ‘That’s great, I can just bask in the glory of it all and get upgraded on Aer Lingus [Ireland’s national airline], but I’m an activist. That’s who I am. How do I take this and make something different in the world?’”

Put simply, his dedication to all things Irish came not from his ethnic heritage, but from a life lived as an activist. While attending the University of Illinois, he formed an advocacy group for graduate students, and after his graduation from Yale Law School he practiced at a firm which specialized in “poverty law”, helping those without the means to help themselves. Bruce Morrison went where he was needed, and in the early 1990s, that place just happened to be Ireland, and he just happened to have an Irish background.

Questions of motive aside, one thing is certain: Bruce Morrison has become a cult figure in the Irish-American community, and the prestige he earned from his work in 1990s isn’t likely to fade anytime soon.

In support of the National Puppetry Festival, we have joined other exhibition venues on campus to show off puppet related materials in our collection. In the reference room you’ll see books describing how to make puppets of all kinds and the theaters and plays to go with them as well as hand puppets from the Phyllis Hirsch Boyson Artifact Collection. The show will be up through August 31.

You can view the puppet exhibit during the hours that our reference room is open: Monday through Friday, 9a.m. to 4p.m.

“The most important value of the practice of puppetry for a child is his introduction to the world of art. In his work, a puppeteer creates and uses many forms of art: he writes, he designs sets, he sculptures his puppets, he costumes them, he uses carpentry techniques to build sets and props, he uses artists’ techniques to color his backgrounds. The puppeteer also becomes a producer, an actor, and a director; perhaps a singer, a musician, or even a lighting director or stage manager. On top of all this, the puppeteer must be skillful with his hands; he must be a manipulator of puppets.

The study of puppetry is not just a hobby; it is a most enjoyable initiation to the world of fine arts.”

—Sir George’s Book of Hand Puppetry, George Creegan, 1966

We’re always looking to improve our new digital repository, either by adding content at a crazy fast pace, or improving the look and design of the pages. Our latest change is to group the collections by overall topics, to help direct researchers to the main areas under which they are likely to search. The categories are:

Activism, and include such interesting items as the charter for the International Military Tribunal which led to the Nuremberg Trials to convict Nazi war criminals after World War II, in the Thomas J. Dodd Papers.

Business and Industry, with items such as this employment card for a worker at the Cheney Brothers Silk Manufacturing Company in Manchester, Connecticut.

Connecticut History, which includes photographs such as this one from the Ona M. Wilcox College of Nursing Records, of children in the pediatric ward of Middlesex Hospital in Middletown, Connecticut.

International Culture and Political Movements, which includes many Spanish language items such as this about the Cazadores de Balmaceda Battalion, in the Valeriano Weyler Papers.

Literary and Artistic Expression has many collections that show the range of human creativity, with such fascinating research items as this photo of Gregg Won in a series of scrapbooks from the Joe Snow Punk Rock Collection.

Political Collections hold many different types of materials documenting the lives of Connecticut political figures, including this video recording from the papers of Bruce Morrison, who ran for the office of Governor of the state of Connecticut in 1990.

University of Connecticut History includes a vast array of materials chronicling UConn’s history from its formation in 1881 as the Storrs Agricultural School to its current status as one of the highest regarded state universities in the United States. This photograph shows an alumni day parade in 1941.

There will be some cross-over among the categories; for example, the Thomas J. Dodd Papers can be found in the categories of Activism as well as Political Collections.

You can also browse the materials by types of media right from the front page. Options include printed books; manuscripts, pamphlets, periodicals; maps; photographs; audio recordings; and video recordings.

Let us know what you think of these improvements and keep checking for more on the way!

By Darryl Thompson

I grew up with one foot in one world and the other foot in another. My father, Charles “Bud” Thompson, was a close friend of the members of one of the world’s last surviving Shaker communities—in Canterbury, New Hampshire—and eventually came to work for them. With the crucial aid of Sisters Bertha Lindsay, Lillian Phelps, and Marguerite Frost and the consent of the rest of the members of the community, he founded the museum that gradually grew into the major historical restoration that can be found there today. As a result, I regularly shuttled back and forth between the Shaker world and that of mainstream American society.

Photograph of Darryl Thompson as a small child, with Eldress Bertha Lindsay of the Canterbury, New Hampshire Shakers

At a very early age I learned to make this transition regularly and easily. At the age of thirteen I became a museum guide and reveled in the role of interpreting one of these worlds to the other. History was the air that I breathed, and so it was natural that I would take a bachelor’s and master’s degree in American history and devote myself to Shaker studies. I wanted to explore unusual aspects of Shaker history that had not been adequately explored before. What fascinated me were the edges in Shaker history—the places in which the two worlds overlapped, the ways in which the Shakers impacted the greater society and those in which the outside world affected them. And, of course, in the whole sweep of American history nothing better symbolized and facilitated the meeting of edges, the unifying of different worlds, the interplay of local cultures and the dominant society than the railroad.

I came to thinking about Shaker connections with railroads through my research into Shaker contributions to forestry, and in the process I discovered that not only did the Shakers have links to both forestry and railroads, but forestry and railroads were intertwined in American history in ways that have often been overlooked. This is a neglected nexus that deserves to be delved into by researchers.

Nineteenth-century America’s railroad industry was a beast with an appetite that would not be satiated, one of the nation’s most voracious consumers of wood in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Sarah H. Gordon in Passage to Union: How the Railroads Transformed American Life, 1829-1929, records that the railroads of the northeastern United States “proceeded to triple their mileage of track in the 1850s, chiefly in the Northeast itself. Miles of track in the United States jumped from 9,021 in 1850 to 30, 626 ten years later.” By the time that the first shot of the Civil War was fired at Fort Sumter, most of the railroads in the eastern part of the country had moved from wood to coal to fire their locomotives, but they still used a good supply of kindling (for which they preferred to use hardwood). In other parts of the country, many railways were still using wood for fuel at the time of the war’s outbreak. The network of railways across the nation had ballooned to 60,000 miles of track by 1870. This meant that wood was needed for the construction, maintenance, and repair of buildings, bridges, railroad cars, cross ties, switch ties, piling, platforms, fencing, guardrails, tunnels, trusses, trestles, telegraph lines, and a variety of miscellaneous items.[1]

However, if railroads were the cause of the destruction of vast tracts of American forests, they also were in the vanguard of reforestation efforts. A railroad company would sometimes experiment with planting trees in order to insure its future supply of wood.

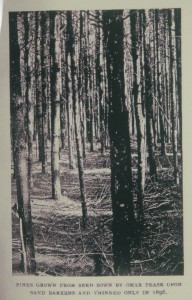

Photograph of Omar Pease’s pines after thinning in the 1890’s. Source: A Paper on Forestry by John Dearborn Lyman, New Hampshire Agriculture Report of the Board of Agriculture, 1894 1 November

For instance, Eric Rutkow in American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation states: “The Kansas Pacific Railroad created three tree stations in 1870, and the idea quickly spread to other train lines.” These experiments in railroad forestry would eventually be abandoned, but they did contribute to the spreading of the idea of growing trees as a crop.[2]

It was the story of Brother (later Elder) Omar Pease, a pioneering, self-taught amateur forester from the Enfield, Connecticut, Shaker village that first led me to investigate Shaker connections to railroads. A member of Enfield Shaker Village’s North Family (each Shaker village was divided into social/governmental/economic units called “families” since they were spiritual families) in the nineteenth century, he planted several hundred acres of white pine on his village’s property, and his plantings included sandy, worn-out tracts of wasteland that served as a dramatic demonstration of the feasibility of turning such barren terrain into profitable timberlands. I am researching his life with the intention of writing a book about this forgotten forester.

I discovered old newspaper articles that showed the Enfield Shakers were among the investors who put up money ($10,000 in the case of the Enfield Shakers) to launch a short line ( its length, including sidings, being only 21 miles) called the Connecticut Central Railroad, which should not be confused with a modern line of the same name that ran from 1987-1998. The Shakers would even open a station on this line that they would operate for years. In early February of 1873 Omar Pease was among those elected by the company’s corporators to the new board of directors. Yet in February of 1875 he is not among the directors listed in an article in the Connecticut Courant of Hartford. However, the May 31, 1875 issue of the Springfield Republican of Springfield, Massachusetts, recorded: “The grading on the Connecticut Central Railroad is now being pushed rapidly through the Shaker Village [at] Enfield, and over a mile from the state line south is entirely completed. The Shakers are making quite a business of getting out railroad ties.”

On July 6, 1875, the Springfield Republican announced that Enfield Shaker Village’s Elder George Wilcox and his Church Family were furnishing all the ties for a short line railroad that was allied to the Connecticut Central. Wilcox must have become part of the Central’s board of directors at some point in 1875, because the February 11, 1876 Boston Traveler includes his name on the slate of directors “re-elected” by the stockholders. Had the Shaker brothers referred to in the May 31st passage been cutting ties under the direction of Pease or Wilcox? The December 24, 1883 Springfield Republican , published just months after Omar’s death, reported the sale of parcels of Shaker timberland by Richard Van Deusen, Omar’’ successor, and recorded that Omar would buy in wood rather than sell it: “Elder Pease would not sell timber, but bought all he could get at a low price. But Elder Van Deusen is selling off the out lots pretty rapidly.”[3]

I put together the information in the two articles and pondered it. Had the men described in the May 31st, 1875 article cut the ties from timber bought in for that purpose by Omar or had they cut down village trees? [4]

I smelled the possibility of some sort of battle or intrigue. Was Omar pressured to leave the board and replaced with Wilcox because Omar was reluctant to cut? The railroad would not have ousted him if he refused to sell. They would just have bought the wood from another source. But could Omar have been pressured to resign by his superiors or his fellow Shakers because they wanted the greater margin of profit arising from cutting down trees on their own property instead of purchasing timber and cutting it for ties? This possibility fascinates me because such an incident would represent Omar’s sudden discovery of a conflict of interest between his traditional role as protector of the Enfield Shakers’ timber resources and his new role in the voracious timber-consuming railroad industry. Such a clash would have resonance with each one of us who is both a consumer of resources and a would-be conservationist.

Thinking that such a conflict might have taken place in Omar’s life and hoping that I might find evidence of it in company documents, I turned to the institution where the records of the Connecticut Central Railroad are located—Archives & Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center of the University of Connecticut at Storrs.

The history field is not well-known for being remunerative, and the challenge for me was how I was going to fund this research trip. I was delighted when a call to Archives & Special Collections revealed the existence of the Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz Travel Grants that help pay for researchers’ expenses when they come to use the great resources of the center. I applied and when I received news that I had been awarded one of the grants, I was overwhelmed with gratitude to both the administration and staff of Archives & Special Collections and to Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz for leaving such a wonderful legacy to aid scholarly research. I soon found myself ensconced in a modest, comfortable, and reasonably-priced motel room. It is hard to describe the joy, eager anticipation, and sense of adventure that I felt every day as I traveled to UConn. I could hardly wait to dive into the treasures of the archive!

And what treasures they were. In addition to the ledgers and papers of the Connecticut Central, there were also materials relating to several other railroad companies that were connected to the Central over the years. In addition to ledgers, these items included board of directors’ minutes, bills, receipts, financial statements, cash books, vouchers, legal papers, contracts and agreements. However, as wonderful as these materials are, Archives & Special Collections’ most precious possession is its hugely knowledgeable and incredibly committed staff. In the days that would follow, I would come to know the great courtesy and help of the staff members who man the desk and the graciousness ofMelissa Watterworth Batt, Archivist for Literary & Natural History Collections. I would also benefit from the extremely valuable assistance, guidance, and advice of Laura Smith, Curator for Business, Railroad, Labor and Organizational Collections. All of these individuals go far beyond the call of duty in aiding researchers.

In Archives & Special Collections’ collections I did not find any information that would explain the departure of Omar Pease from the Connecticut Central’s board of directors and his replacement by George Wilcox. But I found so much more! The materials helped me to reconstruct the history of the Connecticut Central Railroad and allowed me to consider how the ups and downs of that history would have impacted the Enfield Shakers as they operated what became known as Shaker Station on the line. Chartered in 1871 and built in 1875, the Central leased itself to the Connecticut Valley Railroad in 1876 but, since the Connecticut Valley soon defaulted on its second mortgage bonds and was quickly placed in receivership, the Connecticut Central Railroad operated as an independent entity until 1880. In that year of 1880 the Central leased itself to the New York & New England Railroad. One of the great discoveries I made at Archives & Special Collections was a copy of this lease agreement. Also greatly helpful were the bound volumes of board of directors’ minutes of the NY & NE. While I am still trying to understand the exact details of the legalities and financial arrangements, in essence it can be said that the New York and New England held the mortgage on the Connecticut Central. When the latter could not make payments, the NY & NE began proceedings to foreclose in 1885. However, the Central mounted a legal resistance that meant the wrangle dragged on until the closing months of 1887. In the years following its gobbling up of the Connecticut Central Railroad, the New York and New England would itself, in turn, be eventually absorbed by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad.

It has long been claimed among Shaker scholars that the railroad that ran through Enfield Shaker Village only carried freight and not people. It primarily did carry freight, and lumber was one of the things it transported. However, the ledgers of the Connecticut Central that I saw at Archives & Special Collections clearly show income from carrying passengers. A notation that I saw later in an outside source shows that the line did not carry commuters (its schedule perhaps not making it convenient for regular travel to and from individuals’ workplaces) but passengers were definitely riding this train.

Sarah H. Gordon says in Passage To Union: “Organizing nationally was the work of the age, and ticketing records show that railroads made possible the growth of organizations with a national membership of people with middling means.” Agricultural, forestry, and conservation organizations mushroomed into existence with the development of the railroad. Archives & Special Collections contains the papers of the Gold family, including those of T.S. Gold, who served for years as the secretary of the Connecticut Board of Agriculture and who belonged to a myriad of such national, regional, and local organizations. While I have yet to find evidence that Omar Pease had an association with any such group, in the Gold collection I found a very interesting letter from Richard Van Deusen, Omar’s successor, to T.S. Gold. It reveals Van Deusen’s involvement in one of these agricultural organizations. Another letter is to Gold is written on Connecticut State Board of Agriculture letterhead and printed on that letterhead is a list of all members of the board in 1884, the year following Omar’s death. This list will enable further research to find out if Pease had contact with any of these men.[5]

Ken Burns, the nation’s foremost maker of historical documentary films, has said that archives, libraries, and museums contain the DNA of our civilization. Archives & Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center is a treasure house that contains a wealth of material that is a precious resource for scholars. I will always have wonderful memories of the time that I spent there and gratitude that such a special place exists. I invite others to discover the historical riches that can be found there.

Darryl Thompson, Shaker historian, spent years at the Canterbury, New Hampshire Shaker village as the sisters there employed his father, Charles “Bud” Thompson. Mr. Thompson has lectured widely about the Shakers, authored articles about them, assisted in the editing of Shaker-related books, taught classes in Shaker history, and has led tours at Canterbury Shaker Village for decades. An American history instructor at the New Hampshire Institute of Art at Manchester, Mr. Thompson has assisted in the research for Ken Burns’ PBS series on World War II and the national parks and was, along with his father, among the consultants used by Ken Burns in his documentary film The Shakers: Hands to Work, Hearts to God (Walpole, NH: Florentine Films, 1984). In 2015, Mr. Thompson was awarded a Strochlitz Travel Grant from Archives and Special Collections at the University of Connecticut to support his ongoing research.

Sources cited:

[1] Sarah H. Gordon, Passage to Union: How the Railroads Transformed American Life, 1829-1929 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, Publisher, 1997), 106; Sherry H. Olson’s The Depletion Myth: A History of Railroad Use of Timber (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1971), 4. 10, 12 [Table 1: ”Crosstie estimates, 1870-1910”].

[2] Eric Rutkow, American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, New Delhi: Scribner, 2012), 130.

[3] “East Longmeadow “ column, “Hampden County News” section, Springfield Republican (Springfield, Massachusetts), December 24, 1883, 6.

[4] “Annual Meetings. Connecticut Central Railroad…,”Boston Daily Advertiser (Boston, MA), Thursday, February 6, 1873 (Issue 32), 2, column c; “Railroad Matters. New Lay-Out of the Connecticut Central in Enfield—Recovery of Commissioner Northrop—Election,” Saturday, February 20, 1875, Connecticut Courant (Hartford, CT), Vol. 111, Issue 8, 4; “Connecticut” column, Springfield Republican, Monday, May 31, 1875 pg. 6;“Springfield and Vicinity,” column in “Local Intelligence” section, Tuesday, July 6, 1875, Springfield Republican (Springfield, MA), 6; “Railroad News,” Friday, February 11, 1876, Boston Traveler (Boston, MA), 1.

[5] Sarah H. Gordon, Passage To Union: How the Railroads Transformed American Life, 1829-1929 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, Publisher, 1997) , Pg. 181.

From August 10 to 16, UConn will be alive with puppet shows, classes, workshops, exhibitions and events for the 2015 National Puppetry Festival. A special exhibition of puppetry books, artwork, and illustrations from the collections of Archives and Special Collections will be on display from August 1 to 31 in the McDonald Reading Room in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. Find out more in today’s UCONN Today article…

From August 10 to 16, UConn will be alive with puppet shows, classes, workshops, exhibitions and events for the 2015 National Puppetry Festival. A special exhibition of puppetry books, artwork, and illustrations from the collections of Archives and Special Collections will be on display from August 1 to 31 in the McDonald Reading Room in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. Find out more in today’s UCONN Today article…

National Festival Celebrates the Art of Puppetry | UConn Today

Puppeteers from 12 nations on five continents and from 40 U.S. states will converge on the UConn campus during the week of Aug. 10-16 for the 2015 National Puppetry Festival, a whirlwind week of puppet-related activities including workshops, master classes, and performances.

The festival is presented by Puppeteers of America and is expected to be the largest and most extensive gathering of its kind. It will also mark the 50th year of the internationally renowned UConn Puppet Arts Program, which was founded by the legendary Frank W. Ballard. The last time the festival was hosted by UConn was in 1970.

Highlights of the festival will include 30 public performances by more than 25 national and international puppeteers, 30 professional workshops, six visual art exhibitions, “Reel Puppetry” film series, a giant puppet parade, and nightly Festival Pub Showcase. …

On June 18 2015, Dylann Roof, 21 years old, shot and killed nine African-Americans at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. When Roof was apprehended, he wore the flags of Apartheid-Era South Africa and Rhodesia, former white supremacist settler colonial states in Southern Africa. Roof also had Confederate flags hung on his walls and frequented white power websites. These race based murders fueled an ongoing debate about Confederate symbolism and its usage in the private and public spheres. The Alternative Press Collection at the Archives & Special Collections is comprised of fringe publishing from both ends of the political spectrum such as White Patriot and Death to the Klan. The current debate around the Confederate flag draws on long standing uses of historical interpretation and cultural identity dating to the Civil War and Reconstruction era of 1861-1877. As demonstrated in this exhibition currently on display in the Archives through these selected materials from the Alternative Press, Northeast Children’s Literature and Labor collections, figures such as Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, abolitionists John Brown and Frederick Douglass serve as symbolic totems of heritage, spirituality and citizenship. Continue reading

by Casie Trotter, MA student in English Literature at the University of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and awardee of Archives and Special Collections’ Strochlitz Travel Grant.

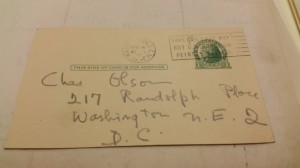

For someone like the poet Charles Olson, visiting an archive is very important. He was all about the “record,” the “document”—two words he often used in and about his own work. It’s not surprising, then, that he preserved much of his life, from personal notebooks to ongoing iterations of new poems and essays. Thousands of letters from people as diverse as his parents, lovers, William Carlos Williams, John Huston, and Carl Jung remain in his files.

I know because thanks to the generosity of Archives and Special Collections and a Strochlitz Travel Grant, I got to spend a week there early this spring, exploring the depths of the Charles Olson Research Collection. Five days was enough to see over eighty unpublished poems, about seventy prose pieces, hundreds of letters, a dozen notebooks and journals, and several books from his personal library. These were only a fraction of the wealth of Olson materials in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, but it was more than enough to strengthen my ongoing research. The archive’s tangible nature enabled me to witness Olson’s creative process on a whole new level. Bottle rings stood out on his leather notebooks; cigarette burns dotted his manuscripts. Sometimes I found letter drafts on the backs of other pieces, whether to the Gas Company or T.S. Eliot.

I know because thanks to the generosity of Archives and Special Collections and a Strochlitz Travel Grant, I got to spend a week there early this spring, exploring the depths of the Charles Olson Research Collection. Five days was enough to see over eighty unpublished poems, about seventy prose pieces, hundreds of letters, a dozen notebooks and journals, and several books from his personal library. These were only a fraction of the wealth of Olson materials in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, but it was more than enough to strengthen my ongoing research. The archive’s tangible nature enabled me to witness Olson’s creative process on a whole new level. Bottle rings stood out on his leather notebooks; cigarette burns dotted his manuscripts. Sometimes I found letter drafts on the backs of other pieces, whether to the Gas Company or T.S. Eliot.

In the process, I uncovered plenty of links to themes and ideas in Olson’s work I’d already been tracing. My MA project at the University of Tulsa developed over the course of two years—starting as a love affair with The Maximus Poems duringmy first semester as a grad student and culminating in this trip to Connecticut a month before graduation. What began as a critical analysis of Olson’s pre-Maximus life and work, an attempt to construct a theoretical framework that led to his Gloucester epic, turned into a very personal journey as I found his ideas and experiences increasingly relevant to mine too. His conflicted relationship with academia mirrored my own; his open and visceral love for the world and who shaped it found a home in the ways I interact with other people. These connections made the project important not only for my academic career, but also gave it larger dimensions that could translate into other parts of my life.

When not in the reading room, then, I also visited Worcester (Olson’s hometown) in nearby Massachusetts and Middletown (where Olson attended Wesleyan). UCONN’s proximity to these locations made it easy to expand the trip into an even more immersive experience. The side tours were particularly valuable ways to encounter the spirit of Olson’s world(s) on some level. Driving through Worcester, sea gulls flew overhead; a Catholic church loomed over the street where newer three-story flats have replaced the one where he grew up. Around Wesleyan, neighborhoods and small businesses evoked a sense of place unique to their environment. This part of the research process was not only how I think Olson would want his work and life to be studied—a poet rooted deeply in the local, the concrete—but helped further tie me to the primary aspects of what it was like to be Charles Olson, almost as meaningfully as the direct experience of the archive itself. I’d been absorbed in his work for so long that feeling my way through his stomping grounds came naturally and powerfully. The commute between campus and my hotel through rural areas provided further reflective avenues for understanding the writer’s world and the backdrop to many of his words that have been the ongoing soundtrack to my grad school years.

The catalyst for my project was discovering Olson’s complicated paternal relationship with Ezra Pound in the aftermath of WWII and EP’s treason trial. Within weeks after Pound was committed to St. Elizabeths Hospital, the younger poet started visiting the elder and providing a source of encouragement. For two and a half years, Pound was another “Papa” in his life. Olson carried drafts of the Pisan Cantos between Pound and his publisher, James Laughlin. Between visits, they corresponded back and forth. The Collection at the Dodd Research Center includes about two dozen postcards from Pound to Olson, among other fragments and pieces the young poet wrote while trying to make sense of a fascist genius. He struggled to understand how someone who could write such beautiful, innovative poetry could also perpetuate such hate-filled ideas.

Although Catherine Seelye edited and published materials from Olson’s “Pound File” at Storrs several decades ago (another great use of their Collection), reading this compilation in paperback form could not compare to observing the pieces firsthand. Seelye’s book made me want to know everything about Olson, to piece together all the people and moments that built him into the giant he was (literally and figuratively). Pound was so crucial to his developing conception of what it means to be a poet that he was the ideal place to start. By the time I got to Connecticut, I’d read all of the Cantos, the Maximus Poems, and spent six months actively compiling and consuming everything else Olson had written before his epic (the Storrs Collection’s unpublished materials also gave me a lot more to work with). While I didn’t get to read everything with equal attention, I’d built enough of a foundation to understand what Olson was capable of and to better appreciate how significant his connections to earlier figures were. And I’d become attached enough to him that he had carried me through some very difficult personal experiences as I was trying to figure out how to “love the world and stay inside it” as he later said in Maximus.

So when I opened the folder with Pound’s postcards, it took a conscious effort not to let my misty eyes drip onto his penciled signature. Since most other scholars (including Seelye) have prioritized Olson’s own words about Pound over what Pound actually wrote to him, these cards were almost like experiencing another world in their relationship. Having studied Olson’s reflections on their frustrated interactions, I was able to reenact his process through each note and gain a better sense of how his feelings were being influenced at the time. Digging through the correspondence files, I unearthed the initial telegram from Olson’s early publisher, Dorothy Norman, asking him to cover Pound’s trial in Washington, and the letter from Laughlin encouraging the young writer to visit his client in the first place. Laughlin also later sent and inscribed a hardcover of the Pisan Cantos to Olson, which remains in his personal library at Storrs. In his WWII-era notebooks, I found his early (unpublished) writings about Pound as the controversy unfolded. But the most heartbreaking postcard was written a few months after Olson stopped visiting Pound in 1948, too weary of the old poet’s racism and closed-mindedness. Wanting to know where he’d gone, EP wrote, “Yes my deah [sic] Charles I just [wonder] wot [sic] are you up to O[?]”. Olson wouldn’t see Pound again for about fifteen years, so this postcard didn’t soften him too much—but I can imagine the effect it still must have had on him after how much energy and affection he’d invested in Pound during some of Olson’s most formative years as a writer.

So when I opened the folder with Pound’s postcards, it took a conscious effort not to let my misty eyes drip onto his penciled signature. Since most other scholars (including Seelye) have prioritized Olson’s own words about Pound over what Pound actually wrote to him, these cards were almost like experiencing another world in their relationship. Having studied Olson’s reflections on their frustrated interactions, I was able to reenact his process through each note and gain a better sense of how his feelings were being influenced at the time. Digging through the correspondence files, I unearthed the initial telegram from Olson’s early publisher, Dorothy Norman, asking him to cover Pound’s trial in Washington, and the letter from Laughlin encouraging the young writer to visit his client in the first place. Laughlin also later sent and inscribed a hardcover of the Pisan Cantos to Olson, which remains in his personal library at Storrs. In his WWII-era notebooks, I found his early (unpublished) writings about Pound as the controversy unfolded. But the most heartbreaking postcard was written a few months after Olson stopped visiting Pound in 1948, too weary of the old poet’s racism and closed-mindedness. Wanting to know where he’d gone, EP wrote, “Yes my deah [sic] Charles I just [wonder] wot [sic] are you up to O[?]”. Olson wouldn’t see Pound again for about fifteen years, so this postcard didn’t soften him too much—but I can imagine the effect it still must have had on him after how much energy and affection he’d invested in Pound during some of Olson’s most formative years as a writer.

In this respect, spending time at the Dodd Research Center was extremely fruitful, both in terms of research and my ever-more intimate connection to a writer who must be studied through primary documents and an empathetic point of view. To do a person like Charles Olson justice requires closer attention than someone without the primal experience of an archive can give. At this point, I may still be working through how my own work will speak for him in the future, but I know that it needed a pilgrimage like this trip to give it firm roots to cling to.

The Archives and Special Collections Reading Room will be closed tomorrow, July 3, as will the University of Connecticut, for the state holiday. The Reading Room will resume its usual hours of Monday through Friday, 9:00am until 4:00pm on Monday, July 6, 2015.