The following guest post is by K-Fai Steele, recipient of the 2019 James Marshall Fellowship. K-Fai (www.k-faisteele.com) is an author and illustrator who grew up in a house built in the 1700s with a printing press her father bought from a magician. She wrote and illustrated A Normal Pig. She illustrated Noodlephant by Jacob Kramer (a Kirkus Best of 2019 picture book) and Old MacDonald Had a Baby by Emily Snape. She also illustrated the forthcoming Probably a Unicorn by Jory John and Okapi Tale, the sequel to Noodlephant. She was a Brown Handler Writer in Residence at the San Francisco Public Library, and the 2018 Ezra Jack Keats/Kerlan Memorial Fellow at the University of Minnesota. K-Fai lives in San Francisco.

The job of a professional children’s book author and illustrator is challenging. There’s no one formula for, or definition of success. The job walks the line between commercial and creative disciplines and requires a bizarre combination of skills: not only writing and illustrating books but being able to perform in front of large varied audiences (toddlers one day, fifth graders the next), deftness at publicity and social media, teaching, and generally being able to project an aura of success and expertise. It can often feel competitive and lonely. And one is paid as a freelancer, so (at least in the United States) there is no economic safety net and it’s hard to plan for a long term career. Another aspect of the job requires constant learning, growth, and improvisation which can either be stressful or exciting and luxurious (if you have the time and space to fully devote to it). Whenever I feel stuck I end up in a library and I’ve learned that some of the best libraries and collections contain public collections of children’s literature preliminary materials. The University of Connecticut is one of these places, and through the James Marshall Fellowship I was given the time, space, and funding to spend time learning and luxuriating in their collection.

If you spend enough time with someone’s work you get a sense of their process; in a way it’s the closest thing you can get to a mentorship. In his essays Caldecott & Co.: Notes on Books and Pictures, Maurice Sendak quotes Alphonse Mucha (a mentor to one of Sendak’s heroes Winsor McKay, the creator of the Little Nemo comic): “I think it would be wise for every art student to set up a certain popular artist whom he likes best and adapt his ‘handling’ or style… when you are puzzled with any part of your work, see how it has been handled by your favorite and fix it up in a similar manner.” It’s a very clever way to get a very good (and free) education.

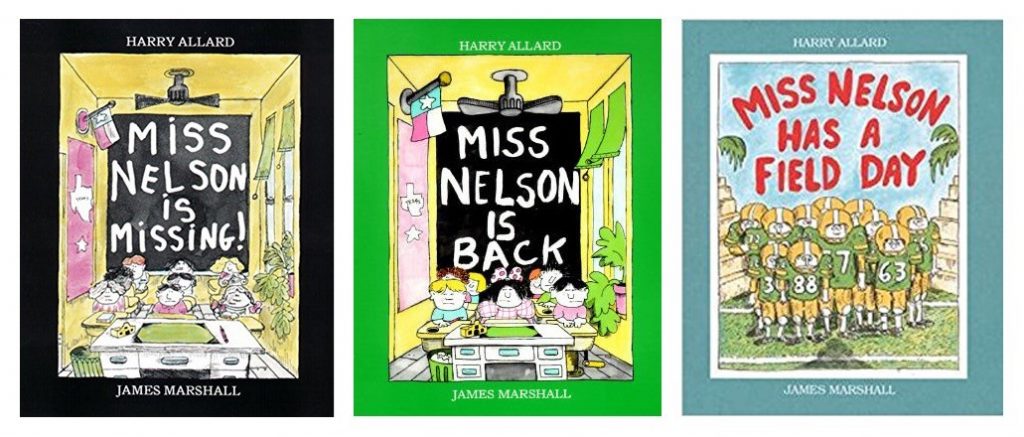

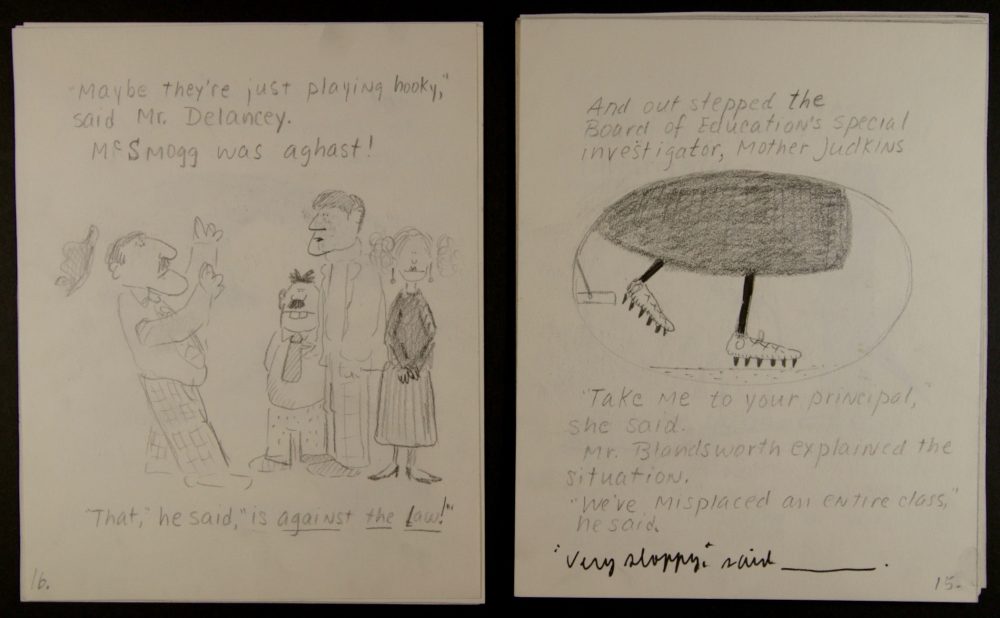

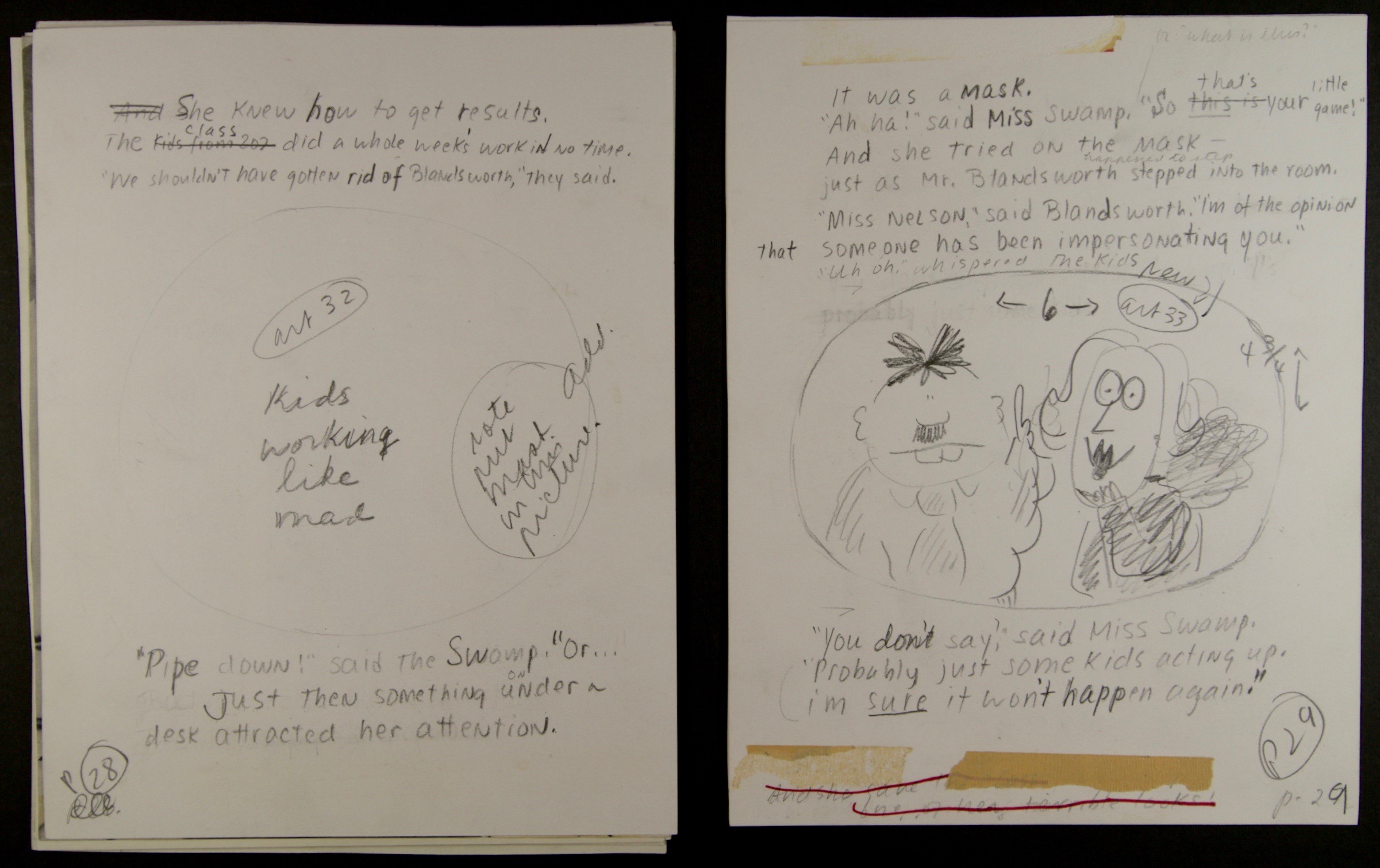

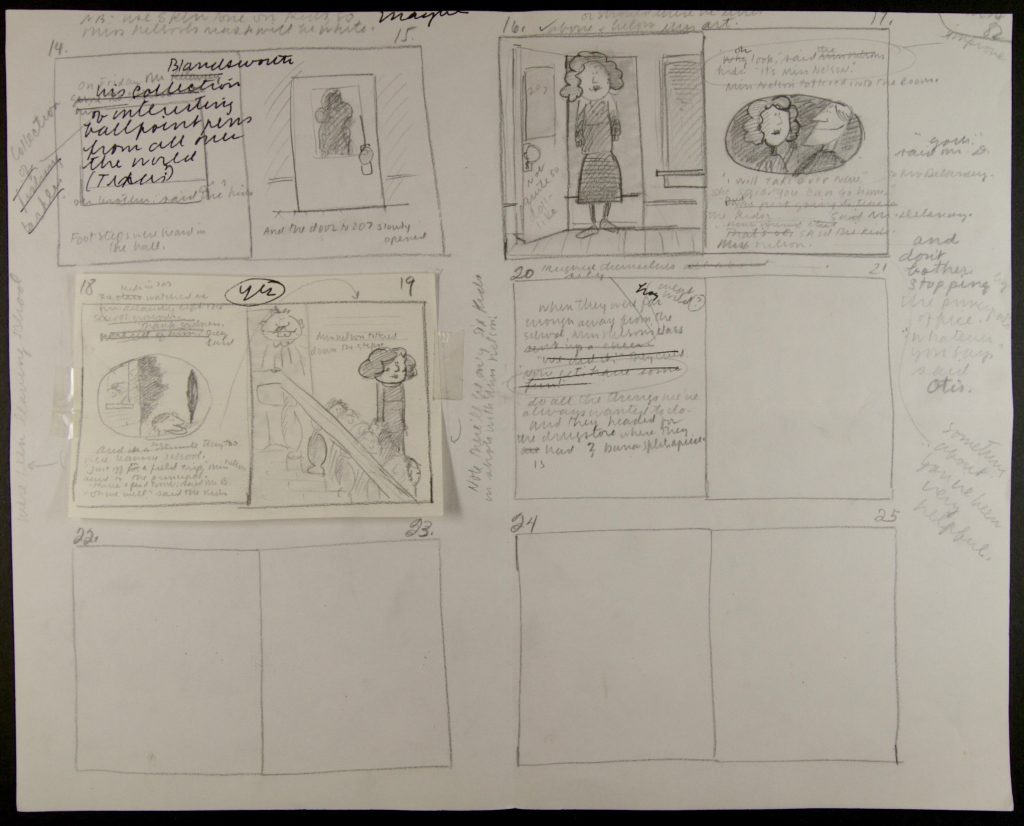

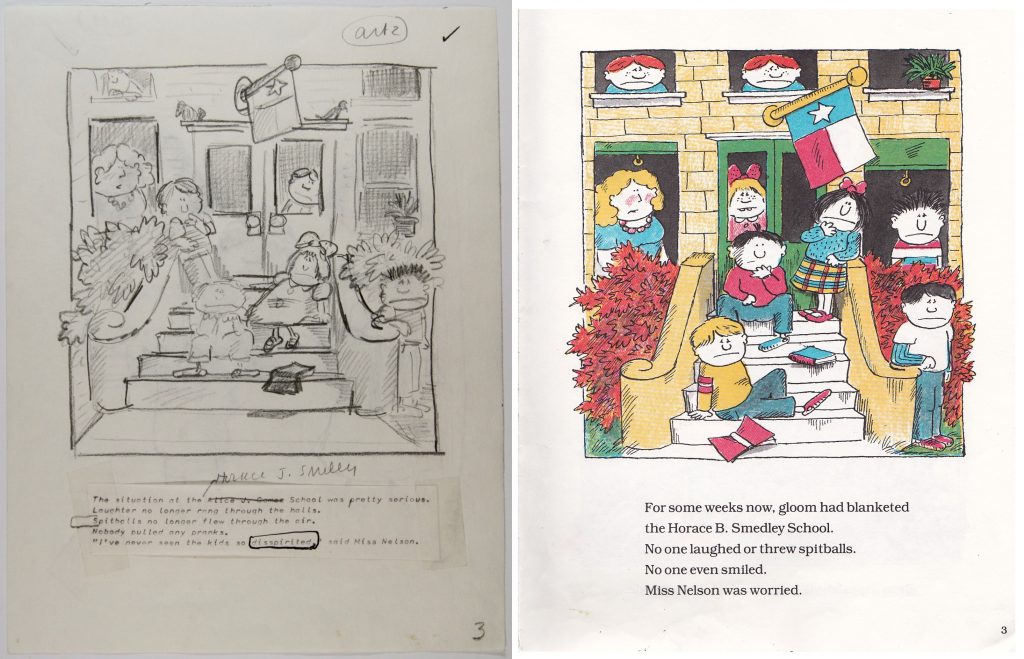

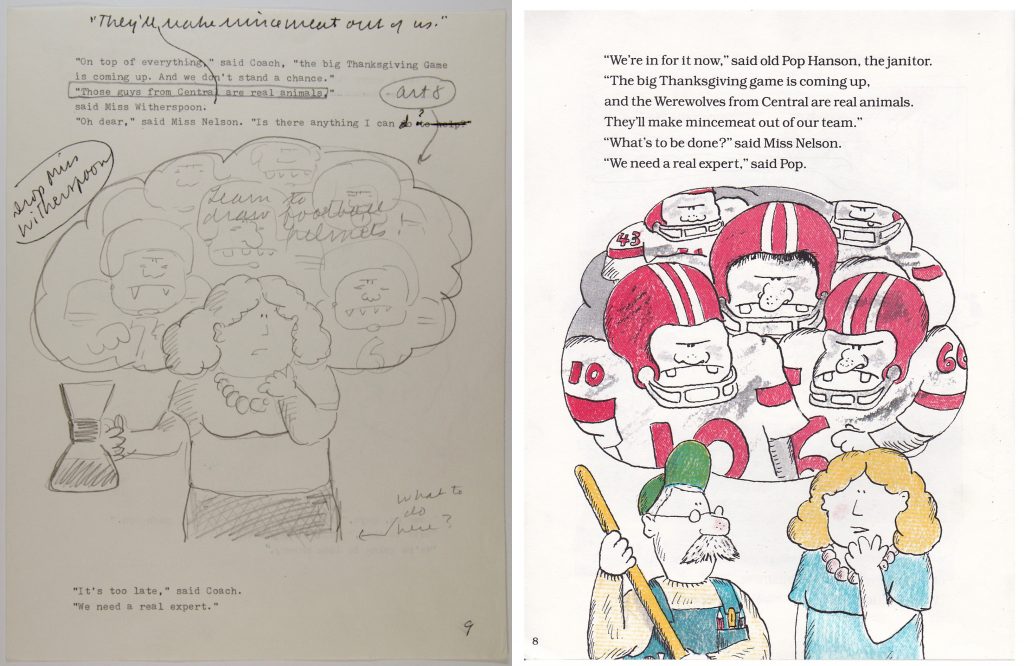

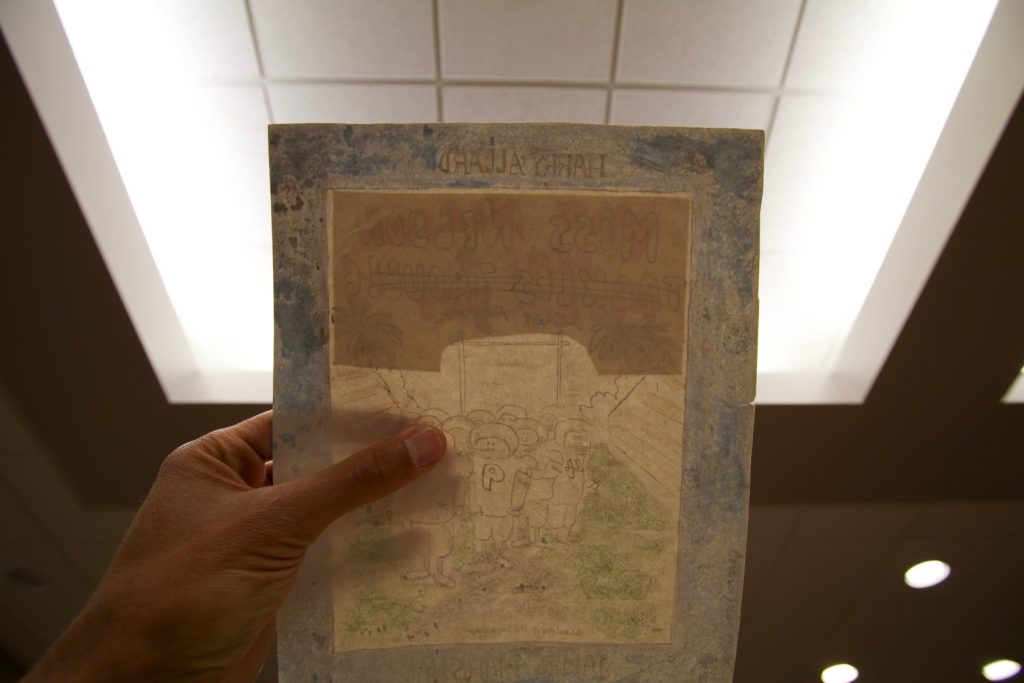

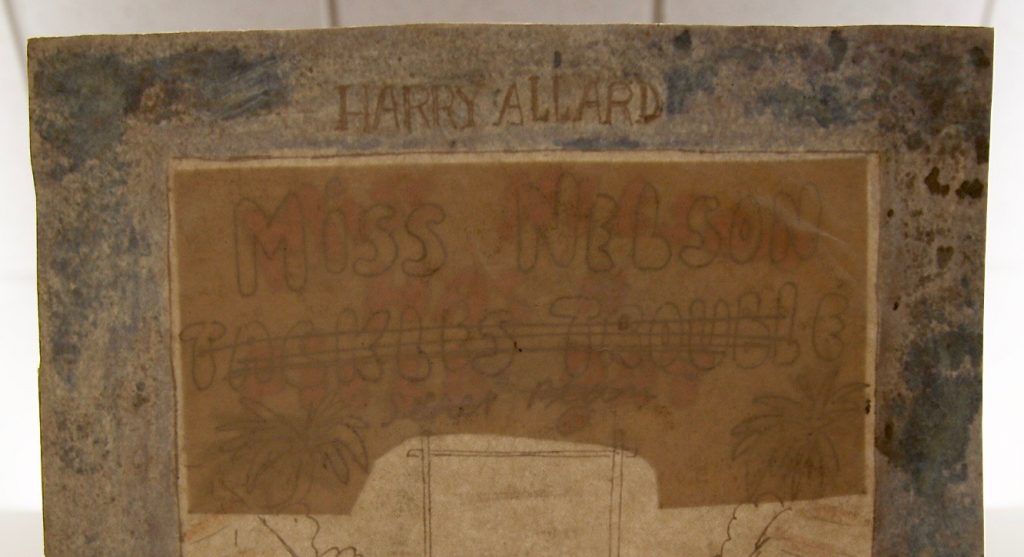

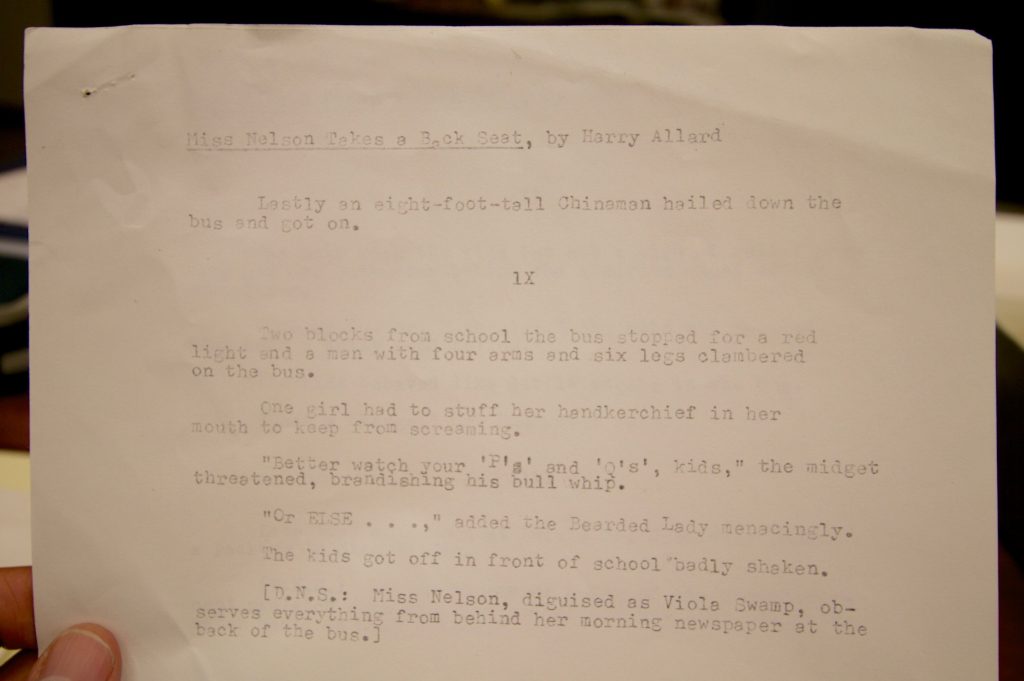

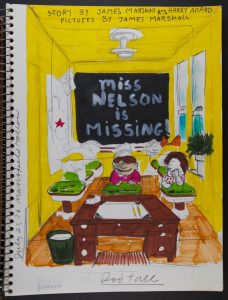

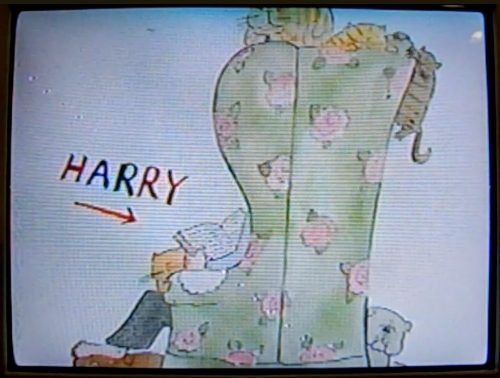

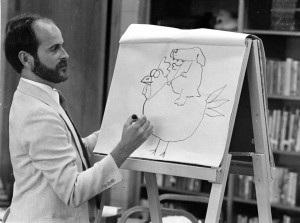

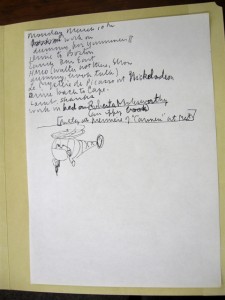

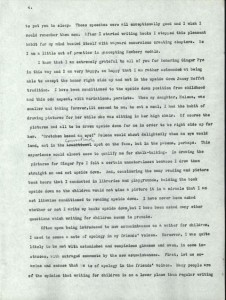

When you read a picture book you only see the finished product. When you visit archives, you see evidence of an often messy process, from sketches and sketchbooks to drafts, manuscripts, and original art. Occasionally you find very special pieces of media, like collections of audio cassette lectures. Francelia Butler was a professor of Children’s Literature at UCONN from the 1960s to 1990s and she invited dozens of authors, performers, and otherwise impressive thinkers to speak in her Children’s Literature 200 class, or as students referred to it, “kiddie lit 101.” She had the foresight to record most of these lectures which are now housed in the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection. James Marshall lived a couple of miles from the UCONN Storrs campus and would give a yearly lecture to her class of primarily undergraduates from 1976-1990 when he was 34 to 48 years old (he died when he was 50). These lectures are mostly off the cuff; he reads a book aloud (often George and Martha or The Stupids), discusses how he came up with ideas for books like Miss Nelson, then takes questions from the audience.

Marshall is the perfect guest lecturer. He is funny, insightful, knows how to work a crowd, and best of all he’s a generous lecturer. He knows how to communicate ideas and make them accessible. At his core he was an educator; he worked professionally as one for a while, having taken over Maurice Sendak’s picture book making class at Parsons. Much of the insights he shares in these recorded lectures are still deeply relevant today, particularly in terms of the creative process and the job of a children’s book creator. Marshall agonized about writer’s block and felt the pressure to make money. He also spoke from the perspective of an outsider who worked extremely hard and never took the joy of making books for granted.

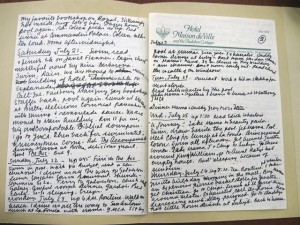

When I arrived at UCONN to start my fellowship I didn’t anticipate that most of my time would be spent using my ears rather than my eyes. I had spent three weeks in 2018 at the Kerlan Collection looking through dozens of his sketchbooks in their collection and since then have tried to read all of his books. I realized I was engaging in a bit of detective work, trying to put the pieces together of a fascinating, talented, funny creator through the crumbs he left behind. Hearing him talk about his work (getting a firsthand narrative) made me feel incandescent. I popped in one cassette after another and was grateful for my fast typing (as of the time of this blog post’s publishing only two of the cassettes have been digitized; according to the archivist it’s an expensive and laborious process). In this post I’m going to share some quotations from these audiocassettes, what surfaced for me as a picture book creator, and what I think other people in the field might find interesting, from his process to how he thought about creative work.

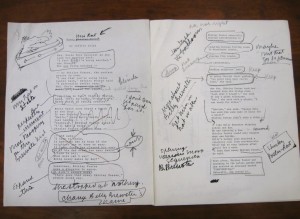

“I start off drawing. I develop a character, make it as crazy as I can, and put that character in a situation. I start with a visual. I couldn’t sit at a typewriter and start a story with words… Drawings first, and then I type it up” (1977, cassette 504). Marshall was known for his strong characters; consider George and Martha, Fox, or The Stupids; the story revolves around them and how they interact with other characters. It’s not so much about plot; Marshall at one point describes George and Martha as a comedy of manners. “I teach my kids at Parsons that to start out you must have a very solid rounded character that lives. I have lots of sketchbooks and I just develop characters as they go along” (1982, cassette 515). Marshall trusted that a good story would organically come out of a good character, particularly if put in an interesting situation where they have to react. There’s a sort of faith required in starting with a character; you don’t know who’s going to show up on the page. You get to know a character by the way they look, their gesture, and how they react to other characters.

Marshall didn’t discuss a specific method that he used to generate stories because he didn’t seem to have one. He described working intuitively, relying on his brain and hand to put together funny ideas. “People ask me often where the ideas come from. If I knew that I could probably spell it out to you… I don’t know where the good stuff happens. It happens when I work a lot, and late at night. Usually If I’ve been working 8-10 hours doing just mechanical stuff I’m so tired all my defenses are down. I’m not worried whether it’s going to be a success or not, and some nutty idea comes in, it’s like someone else told me that… You know it came from inside your head but you don’t know why or how” (1979, cassette 506). “What I do is try to sit down, and if I fall down and start laughing that’s a good sign” (1980, cassette 508). It seemed that he didn’t examine his story-making because he was worried that if he figured it out he would lose the muse. “What I do is intuitive and I don’t know why I’m sitting here talking to you because I don’t really know why I do what I do, and to talk about it is a little scary to analyze it. I’m afraid if I look at it too much and try to figure out what I do it’ll go away” (1985, cassette 525). Since he relied so heavily on intuition his fear of losing the muse makes sense. He mentioned this fear in several lectures, and it seems to really be the thing he feared the most: the bucket going down the well and coming up dry.

Perhaps this fear came from a sense of what we would now describe as imposter syndrome. “Often I have so much trouble coming up with endings. It’s just like hell. Because you think here I am, this is what I do for a living, but maybe I’m not so good anymore, maybe I never had any talent in the first place” (1987, cassette 527). Marshall continues in a 1990 lecture, “I’ve thrown up in my studio from the fear of thinking I’m all finished, I’m washed up, I have no talent, I can’t even write one of these dumb books, I can’t think of another joke” (cassette 531).

Perhaps it came because making good books for children is deceptively challenging. There isn’t a roadmap, particularly when you’re making something that pushes boundaries of humor, style, etc. “When I’m drawing it’s like heaven, even when it’s not going so well I’m really, really happy. I feel connected, I feel like I belong. Why it’s such hell to get started, I don’t know. I guess it’s because I’m scared. Chekhov had the same feeling, he thought he was no good, couldn’t cut it. If a guy that great can have those feelings maybe it’s not so abnormal, maybe you should have those feelings of insecurity. Because if you’re absolutely sure that what you’re doing is brilliant what you’re doing is copying yourself or copying someone else” (1988, cassette 529).

Or perhaps the pressure was more external; he needed to make more books in order to keep his career (and income stream) flowing. This is when his practice of writing intuitively probably chafed against a demanding publishing schedule. “I have an artistic problem: when a book is successful, editors like to see success perpetuated, so they hire you to do a sequel. I’ve done so many sequels but I haven’t gotten any quite right. It’s the hardest thing in the world to capture the spirit of another book when you don’t have an idea. I’m doing three picture books, all three are sequels, and I’m stalled on all three. It’s a sickening feeling to think that you’re going to have to turn that money back and that you’ve run out of ideas” (1985, cassette 525). Marshall’s output was prodigious; he made around eighty picture books during his 50-year life. What is the result of working faster than your machine wants to run? The quality may suffer, at least in the creator’s eyes. In one lecture Marshall says, “I’ve made 60 books and only about 20 am I really proud of” (1983, cassette 517).

Marshall’s writing and drawings have a sense of lightness and ease to them, particularly in the way he draws characters and communicates their emotions through their eyes (often simple dots). In 1997 several years after Marshall’s death, Sendak wrote in the New York Times, “Much has been written concerning the sheer deliciousness of Marshall’s simple, elegant style. The simplicity is deceiving; there is richness of design and mastery of composition on every page. Not surprising, since James was a notorious perfectionist and endlessly redrew those ”simple” pictures.”

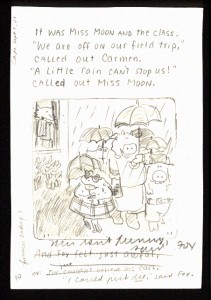

Marshall drew with joy, and this is most evident in UCONN’s collection of his sketchbooks. In his lectures he talks about the phenomenon I hear a lot of other author-illustrators experiencing when they move from sketches to final art; some freshness is lost. “It’s when you have to prepare something that’s going to get published, at least not only me but everyone I know in the business, you get tense and frightened because this is going to be out there, there are going to be 20,000 copies of this, and it gets tighter and tighter. The best stuff I’ve done of any quality is in my sketchbooks and I pick that stuff out and I’m like why can’t I do that here?” (1984, cassette 520). Perhaps it’s different when you’re making final art because you know that you have an audience, that you’re relying on the art to make money. It’s less about amusing yourself; it goes from a private activity to a very public one. “The sketches are so much more interesting, that’s the fun part. It’s when you do a line that you know is going to be published you start to clutch and tighten up. I’m just now learning to do books and get a line that’s going to be published that’s as good as the one in the sketches. I’d love to take my old sketches out and publish them. I feel so much more comfortable with them. I don’t know if it’s a fear of success or fear of failure, it’s a really terrifying process to go through” (1981, cassette 511).

Marshall also shared insights into how he thought he was perceived by gatekeepers of the industry, specifically librarians who had a more traditional sense of illustration and who also reviewed books and selected for awards (in particular the Caldecott Award). “I work in basically creative periods of about 3 weeks that’s all I can stand… This is dangerous because when I tell librarians (“conventional people”) if I tell them how short it takes me to do a book I can see in their eyes my stock going down. You have to tell them you worked 5 years on this book and you’ve drawn with the blood of your slaughtered children and then it’s a masterpiece” (1985, cassette 519) Marshall drew somewhat injured and bitter conclusions about why he had been overlooked, “People who are in children’s books are ashamed of being in children’s books. People on committees want to pick a book that shows they’re an important, art-minded profession” (1985, cassette 519).

Sendak wrote that Marshall “paid the price of being maddeningly underestimated — of being dubbed ”zany” (an adjective that drove him to murderous rage)… he was dismissed as the artist who could — or should or might — do worthier work if he would only dig deeper and harder. The comic note, the delicate riff were deemed, finally, insufficient. James knew better, of course, and he was right, of course, but he suffered nevertheless. There was nothing he could do to impress the establishment; that was his triumph and his curse. Marshall did fulfill his genius, and its rarity and subtlety confounded the so-called critical world. The award-givers were foolish enough to consider him a charming lightweight, and when Caldecott Medal time came around, they ignored him again and again.” Marshall also spoke about competition in the children’s literature world, which undoubtedly was connected to him not feeling appreciated, validated, or celebrated by the people who held power. “The world of children’s books I used to say is a nice world. It is not, it’s a nest of vipers, we all hate each other… we’re very competitive” (1982, cassette 513).

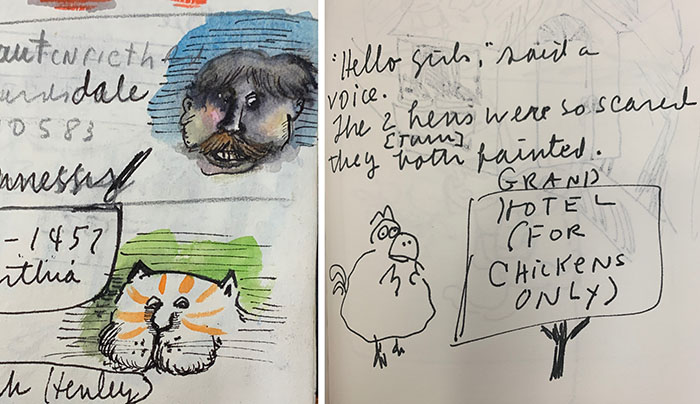

It was interesting to hear Marshall talk about the other authors and illustrators he was in community with. In nearly every lecture he named some of the people who he thought were doing the best work in children’s literature: Arnold Lobel, Edward Gorey, Maurice Sendak, Tomi Ungerer, Rosemary Wells, William Steig, Edward Ardizzone, and Quentin Blake were all mentioned. “If you want to see some magnificent small jewels, look at the Frog and Toad books. I thought, oh I can do that. First I saw Sendak: oh, I can do that. Lobel: oh I can write stories about two friends too. They sort of gave me confidence. I didn’t know how hard it is. Sometimes it’s fun, sometimes it’s impossible to try and write two-page stories with a beginning, middle, and end” (1990, cassette 532). He clearly adored Maurice Sendak, who he referred to as “the granddaddy of us all” (1980, cassette 508) in terms of contemporary illustration. The Maurice Sendak Collection of James Marshall at UCONN contains several of Marshall’s books that he inscribed for Sendak, including a rare copy of his first illustrated book, Plink, Plink, Plink (1971) by Byrd Baylor which Marshall said “sunk, sunk, sunk” due to the “awful poems and awful pictures” (1977, cassette 504).

This collection of recordings is a very rare and special item; you just don’t find a lot of authors speaking in their own words, at length, about their work. I think that this speaks to Marshall’s experience as an educator; someone who has good communication skills, a sense for what might be interesting content, respect for their audience, a willingness to be generous with the knowledge they possess, and their love for the work.

One of my favorite things that Marshall said had to do with the joy of getting to do the thing you love most in the world as a job. “To be able to support myself by doing what I really like to do best and by being creative, I never dreamed that that could be. I was raised with protestant puritant [sic] ethics. In Texas you had to bring home the bacon by doing stuff that you hated; my daddy hated his job, my mama hated being a housewife, everyone in my family hated everything. I thought when I became an adult I had to just swallow it. It’s not true. It’s a wonderful, wonderful feeling” (1983, cassette 517). This is something that you can easily lose sight of a children’s book maker as you get involved in the day-to-day of trying to meet deadlines, negotiate with art directors, redo cover art, schedule school visits, make money and budget wisely, etc. I’m writing this blog post in late spring 2020 in the midst of a global pandemic which has made clear that nothing is guaranteed, in particular human life, especially those most vulnerable in our society. For a while I wasn’t sure if books or art even mattered. But of course they do, and the act of engaging in joyful creative work is a much-needed lifeline, as Marshall attested to during his short life, ended by the HIV/AIDS pandemic in 1992. “One of the most wonderful things in the world is to do creative work, it is the greatest high, it makes your life come together” (1987, cassette 527).