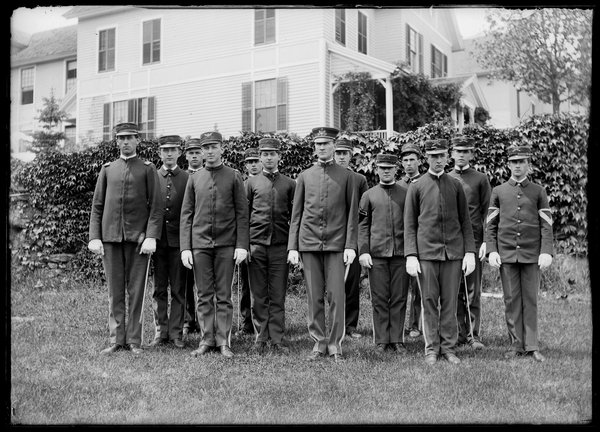

This photo was taken in 1906 by Connecticut Agricultural College (later UConn) professor Harry L. Garrigus, of the ROTC cadets at the college.

Author Archives: Laura Smith

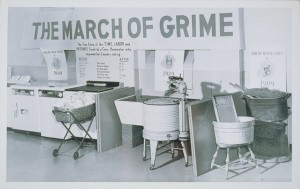

The March of Grime

Another “Hard Work” photograph

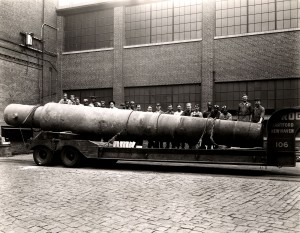

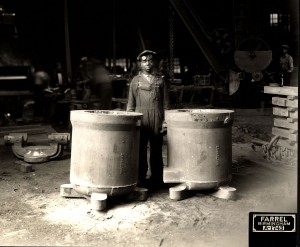

Our new exhibit — Hard Work: Connecticut’s Laborers in the Industrial Age

This exhibit shows scenes of Connecticut’s workers doing Hard Work. Capital H, Capital W. The kind of work where you surely need the brains but if you ain’t got the brawn it’s not gonna happen. And we’ve got plenty of photographs in our business collections showing the men and women in the state in various depictions of work where some of the main job requirements are muscle and sweat. I’m sure tears were there somewhere but the photographs don’t really show that.

In the late 19th and early 20th century — a time period in America known for big industry — Connecticut was one of the major players, producing brass, iron, steel, tools, textiles and more for the state, the country, and the world. These products didn’t just happen. It took a workforce of thousands, many of them new immigrants who flocked to Connecticut for these types of jobs, to produce, to make, to build, and to work.

Are trains faster today than they were 100 years ago?

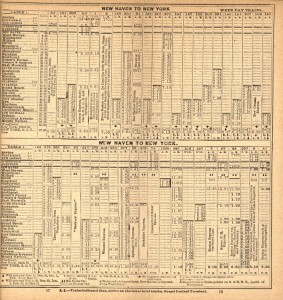

Was train travel from New Haven, Connecticut, to New York City faster 100 years ago than it is today? Here are two pages from the public timetable of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad from September 1914:

If someone took the “Banker’s Express” from New Haven at 8:00a.m. he (and in that day and age it was always a “he”) would get to New York City at 9:44a.m.

If someone took the “Banker’s Express” from New Haven at 8:00a.m. he (and in that day and age it was always a “he”) would get to New York City at 9:44a.m.

How does that compare to today?

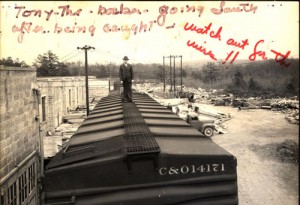

An odd railroad photograph

Photograph for documentation of an accident involving the conductor of the train and wiring above the cars, taken on April 18, 1947

This photograph was taken to document a train accident on an industrial siding in Dayville, Connecticut. Apparently the man standing on top of the freight car was there to show how the conductor of the train was injured when he came into contact with wiring. Someone amusingly wrote “Tony-the-hobo going South after being caught — watch out for the wires!!” on the print.

This print was recently donated by donor Edward J. Ozog.

A traveling preacher with Connecticut ties

It happens with delightful frequency that historical treasures find their way to our archives in round-about ways. Last week I received a call from UConn history professor Christopher Clark, who had been contacted by a woman in Texas who owned a letter that had a connection to eastern Connecticut. Dr. Clark put me in touch with Ms. Anne Bowbeer of San Antonio, who described the letter and asked if I would like to include it in the archive. I most certainly would!

![Letter from S. Hitchcock of Reidsville [possibly North Carolina] to Michael Richmond of Windham County, Connecticut, August 13, 1835](https://blogs.lib.uconn.edu/archives/files/2014/08/2014-0113_ms1.jpg)

Letter from S. Hitchcock of Reidsville [possibly North Carolina] to Michael Richmond of Windham County, Connecticut, August 13, 1835

Reidsville August 13th A.D. 1835

My dear Sir I expected to have written to you, long before this time. But in consequence of the plentiful harvest and few Labourers in this region I have delayed writing till now. By letter received from Connecticut I have understood that my temporal concerns required that I should once more journey to my native town. And as any field of labour in this Country is verry extensive; and my whole time devoted to religious service I have waited [for] the vacancy of a fifth Sabbath that I might consistently[?] leave my circuit for a few days; you may therefore expect (If the Lord will) me to attend meeting at your Meeting house on the fifth Sunday in August at the usual hour of meeting. You are therefore at liberty to make the appointment if you think it best. I greatly desire your prosperity as a free religious; people had[?] should have much to write; But as I hope soon to see you face to face I defer writing more. Serve the Lord and Fare Well. Your Respectfully S. Hitchcock.

The letter brings up a lot of questions — who was S. Hitchcock? What led him to leave Connecticut? Who was Michael Richmond?

Perhaps an inquisitive student from the region will choose to research these men and their place in history. For now we’re grateful to Ms. Bowbeer for her thoughtful decision to send the letter to us and allow us to save it for another 180 years and beyond.

Tracking Down the Goods sold on Main Street USA

[slideshow_deploy id=’4475′]

Kirin J. Makker is an Assistant Professor of Architectural Studies at Hobart William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York, and the recipient of a 2014 Strochlitz Travel Grant. Travel Grants are awarded bi-annually to scholars and students to support their travel to and research in Archives and Special Collections. Part of the following essay also draws on materials at Winterthur Library, where this year Dr. Makker is also being supported by a National Endowment for the Humanities residential fellowship. To learn more about the book she is working on, please go here.

I went to Archives & Special Collections of the University of Connecticut Libraries to spend a couple of days sifting through the records of the E. Ingraham Company. I’m working on a book about the history of small town development when it boomed around 1900 and a major part of my research methodology involves following the trail of company goods right at the moment big capitalism really spread its wings (see blog The Myths of Main Street). My hope is to track where a handful of companies sold their goods in order to describe a product’s national distribution, and hence its availability across small town America. I have found, and my research will argue, that one of the reasons that small town America is such a consistent idea in the nation’s cultural language is that the goods exchanged there had both local and national parameters. Some of this research has had to do with companies that literally produced small town America: the storefronts, the brick-making machinery, the lamp posts. But other parts of the research is about the everyday objects that were sold in small towns, and how most of them during the period of small town America’s boom were not made locally or even regionally. The retailers were locals, but the items for sale on Main Street were typically sourced from manufactories or large distributors in cities.

For example, a $2 watch made by the E. Ingraham Company in 1898 was made in Bristol, Connecticut but was sold on several thousand Main Streets all across America in general stores or small jewelry shops. Ingraham was after the mass market that the very successful company Robert H. Ingersoll had been selling to. Ingersoll had shrewdly introduced a $1 pocket watch, the “Yankee,” in 1892, stumbling into an enormous mass market of working- and middle-class consumers interested in owning timepieces they could afford.

Although Ingraham couldn’t make a quality watch for that little (the Ingersoll watches, not surprisingly, were cheap but not known for quality), they did start making a $2 watch by 1900 and these sold quite well, judging by how long they produced this watch (until the 1950s). Yet, when I dug around the Ingraham Company archives in Archives & Special Collections, I had some trouble finding records to support their efforts to take a share of the Ingersoll Yankee’s market.

As I said, I set out to spend all my time on the Ingraham Clock Company archive. However, it turned out that what I was really hoping to find within my time period (1870-1930, Main Street’s ‘boom period,’ so to speak), wasn’t so easy to cull. I had set out to identify names and locations of retailers who ordered Ingraham watches for their shops on Main Streets in towns all over the country. Or possibly find advertising by the company that included testimonials from retailers in small towns. I have found these types of testimonials for Elgin watches of the period, so I was hopeful. However, most of the Ingraham Company’s order records in Archives & Special Collections show sales to large distributors in cities. In addition, most of the records in the collection were from the 1940s and 50s (just the luck of what records survived, unfortunately). I did find contract letters with Sears from the 1930s, in which the mega-retailer agreed to uniquely market Ingraham watches in their stores and catalogs. But I needed letters with Sears or Montgomery Ward from around 1905 or more information about the distributors who bought $2 watches in large volume and then re-sold them in small batches to shopowners in the nation’s towns. That information may or may not be available in any archives, so in the end, the Ingraham $2 pocket watch story might not make it into the book.

However, as typically happens for me, as soon as I turn my attention away from one enticing collection, I find myself in the midst of a host of material that suits some other aspect of the book research. (Nothing, I tell you, NOTHING beats the fun of serendipity in the archives!)

What did I find? A glorious collection of ephemera and sales records for the E.E. Dickinson Witch Hazel Company of Essex, Connecticut. One of the chapters I’m writing is on the variety of goods and services related to a townsperson’s health, all of which they could get on Main Street. There was quite a bit of overlap between what was a “good”, a “service” and also a ways to participate in community life in the many shops and offices in downtown small town America between 1870-1930. For example, one might go to the town druggist to purchase a prescription from a local doctor, a box of candy, or sit at the soda fountain and gab with friends over a strawberry fizz. Barber and beauty shops were where one got one’s haircut or styled, but also where one socialized with a gendered group of residents. Doctors were where one received diagnoses and health recommendations, but also where one might purchase a drug remedy (many physicians made their own drugs during the early part of my period of study). I’m interested in looking at how Americans living in small towns attended to their health needs because understanding healthcare history before drug and health insurance, medical malpractice, and managed care may be valuable for understanding our contemporary struggles with the industry. Or at the very least, this history offers an interesting comparison to the practices and standards the current day.

The story of Dickinson’s Witch Hazel fits right into this chapter because it was a factory-produced astringent that became an everyday remedy for minor ills. It was sold all over the country in drugstores and used extensively in small town doctor’s offices. And this time, I found records that show national distribution. For example, during the mid-1920s there were many letters between Dickinson executives and the Druggist Supply Corporation (DSC). The DSC was made up of retailers across America, many of which were located in small towns (Fresno, CA; Peoria, IL; Ottumwa, IA; Burlington, IA; Fort Wayne, IN; Rock Island, IL among many others). By working with that organization, Dickinson assured that they would get their product into those shop owners’ hands.

There were also several large company scrapbooks with hundreds of ads, letters from happy vendors, testimonials, and the like. For example, there was a letter from the owner of a drug store in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He was thanking the Dickinson Company for sending him a set of booklets to give out to his customers with their purchase of a bottle of Witch Hazel. With his letter of thanks, he included a clipping from the local newspaper which documents his announcement of the Witch Hazel booklet’s availability. He also noted that he gave a bunch of the booklets to a teacher at a nearby rural school for their students.

I could go on and on, but you’ll have to wait for the book. Overall, my visit to Archives & Special Collections was a success, both in terms of clarifying the role of Ingraham in the book and adding to my health-related goods and services chapter. [KJM]

Railroad photographs now online

We’ve blogged previously about our efforts to develop the Connecticut Digital Archive; you’ll recall that many of the Nuremberg Trial documents in the Thomas J. Dodd Papers are now online. We’re putting more content online now and one of our latest set of photographs is the New Haven Railroad Glass Negatives Collection.

To see the photographs when you visit the Connecticut Digital Archive, click on “Browse Digital Collections” and then on “New Haven Railroad Glass Negatives Collection.” There are 148 photographs of New Haven Railroad cars — baggage, parlor, dining, sleeping and coaches — from the early 1900s. Many of the exterior views of the cars are accompanied by an interior view, like the photograph above of parlor car 2153.

Another way to view this particular set of photographs is from the finding aid to the collection. Go to the finding aid and scroll down to the descriptions of the individual photographs. You’ll find a link to the image in the digital archive. You really can’t get any cooler than that.

This is just the beginning of our delivering our resources to you online. Stay tuned for more!

Hartford dandies

The Somersville Manufacturing Company Records

The Somersville Manufacturing Company, maker of fine heavy woolen cloth, was established in 1879 in Somersville, a village in the town of Somers, Connecticut, by Rockwell Keeney. For the company’s entire 90 year history it was owned and run by Rockwell’s descendents.

Advertisement for woollens made by the Somersville Manufacturing Company in Somersville, Connecticut, ca. 1950s

Last year Mr. Timothy R.E. Keeney, Rockwell’s great great-grandson, contacted Archives & Special Collections to discuss the donation of the company’s records, which were stored in his home in Somersville. We found the records to be unique, accounting for the entire history of the company from its founding in 1979 to the point where it shut its doors in 1969. The documents themselves were a treasure trove, ranging from administrative and financial files and volumes to marketing material, photographs and scrapbooks, detailing not only the life cycle of the company but also the Keeney family. Mr. Keeney graciously gave us plenty of details about his family’s extensive and affectionate family; one fascinating aspect of the collection includes hundreds of letters written in the late 1930s and World War II years by his grandfather Leland Keeney to various members of the family.

The finding aid to the records is available at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/931.

Remembering the New England Hurricane, September 21, 1938

[slideshow_deploy id=’3997′]

The New England Hurricane of 1938 was one of the most famous of weather disasters in the region’s history and for many years the standard upon which all other hurricanes were held. The devastation was enormous: after making landfall as a Category 3 hurricane on September 21 it is estimated to have killed between 682 and 800 people, damaged or destroyed over 57,000 homes, and caused property losses estimated at $306 million ($4.7 billion in 2013).