By Darryl Thompson

I grew up with one foot in one world and the other foot in another. My father, Charles “Bud” Thompson, was a close friend of the members of one of the world’s last surviving Shaker communities—in Canterbury, New Hampshire—and eventually came to work for them. With the crucial aid of Sisters Bertha Lindsay, Lillian Phelps, and Marguerite Frost and the consent of the rest of the members of the community, he founded the museum that gradually grew into the major historical restoration that can be found there today. As a result, I regularly shuttled back and forth between the Shaker world and that of mainstream American society.

Photograph of Darryl Thompson as a small child, with Eldress Bertha Lindsay of the Canterbury, New Hampshire Shakers

At a very early age I learned to make this transition regularly and easily. At the age of thirteen I became a museum guide and reveled in the role of interpreting one of these worlds to the other. History was the air that I breathed, and so it was natural that I would take a bachelor’s and master’s degree in American history and devote myself to Shaker studies. I wanted to explore unusual aspects of Shaker history that had not been adequately explored before. What fascinated me were the edges in Shaker history—the places in which the two worlds overlapped, the ways in which the Shakers impacted the greater society and those in which the outside world affected them. And, of course, in the whole sweep of American history nothing better symbolized and facilitated the meeting of edges, the unifying of different worlds, the interplay of local cultures and the dominant society than the railroad.

I came to thinking about Shaker connections with railroads through my research into Shaker contributions to forestry, and in the process I discovered that not only did the Shakers have links to both forestry and railroads, but forestry and railroads were intertwined in American history in ways that have often been overlooked. This is a neglected nexus that deserves to be delved into by researchers.

Nineteenth-century America’s railroad industry was a beast with an appetite that would not be satiated, one of the nation’s most voracious consumers of wood in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Sarah H. Gordon in Passage to Union: How the Railroads Transformed American Life, 1829-1929, records that the railroads of the northeastern United States “proceeded to triple their mileage of track in the 1850s, chiefly in the Northeast itself. Miles of track in the United States jumped from 9,021 in 1850 to 30, 626 ten years later.” By the time that the first shot of the Civil War was fired at Fort Sumter, most of the railroads in the eastern part of the country had moved from wood to coal to fire their locomotives, but they still used a good supply of kindling (for which they preferred to use hardwood). In other parts of the country, many railways were still using wood for fuel at the time of the war’s outbreak. The network of railways across the nation had ballooned to 60,000 miles of track by 1870. This meant that wood was needed for the construction, maintenance, and repair of buildings, bridges, railroad cars, cross ties, switch ties, piling, platforms, fencing, guardrails, tunnels, trusses, trestles, telegraph lines, and a variety of miscellaneous items.[1]

However, if railroads were the cause of the destruction of vast tracts of American forests, they also were in the vanguard of reforestation efforts. A railroad company would sometimes experiment with planting trees in order to insure its future supply of wood.

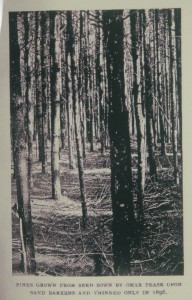

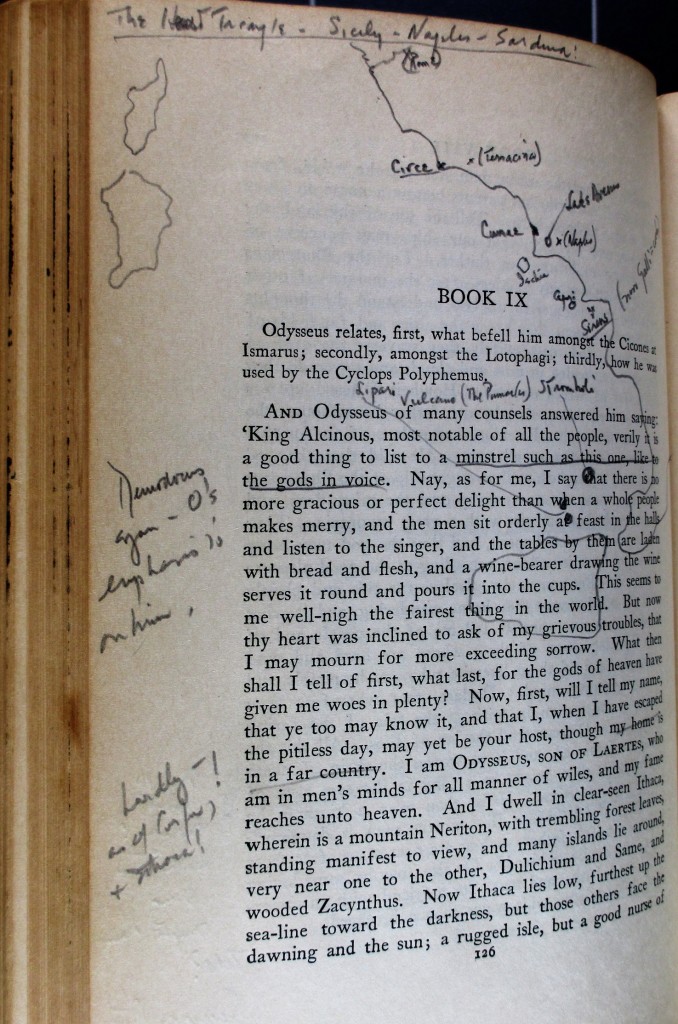

Photograph of Omar Pease’s pines after thinning in the 1890’s. Source: A Paper on Forestry by John Dearborn Lyman, New Hampshire Agriculture Report of the Board of Agriculture, 1894 1 November

For instance, Eric Rutkow in American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation states: “The Kansas Pacific Railroad created three tree stations in 1870, and the idea quickly spread to other train lines.” These experiments in railroad forestry would eventually be abandoned, but they did contribute to the spreading of the idea of growing trees as a crop.[2]

It was the story of Brother (later Elder) Omar Pease, a pioneering, self-taught amateur forester from the Enfield, Connecticut, Shaker village that first led me to investigate Shaker connections to railroads. A member of Enfield Shaker Village’s North Family (each Shaker village was divided into social/governmental/economic units called “families” since they were spiritual families) in the nineteenth century, he planted several hundred acres of white pine on his village’s property, and his plantings included sandy, worn-out tracts of wasteland that served as a dramatic demonstration of the feasibility of turning such barren terrain into profitable timberlands. I am researching his life with the intention of writing a book about this forgotten forester.

I discovered old newspaper articles that showed the Enfield Shakers were among the investors who put up money ($10,000 in the case of the Enfield Shakers) to launch a short line ( its length, including sidings, being only 21 miles) called the Connecticut Central Railroad, which should not be confused with a modern line of the same name that ran from 1987-1998. The Shakers would even open a station on this line that they would operate for years. In early February of 1873 Omar Pease was among those elected by the company’s corporators to the new board of directors. Yet in February of 1875 he is not among the directors listed in an article in the Connecticut Courant of Hartford. However, the May 31, 1875 issue of the Springfield Republican of Springfield, Massachusetts, recorded: “The grading on the Connecticut Central Railroad is now being pushed rapidly through the Shaker Village [at] Enfield, and over a mile from the state line south is entirely completed. The Shakers are making quite a business of getting out railroad ties.”

On July 6, 1875, the Springfield Republican announced that Enfield Shaker Village’s Elder George Wilcox and his Church Family were furnishing all the ties for a short line railroad that was allied to the Connecticut Central. Wilcox must have become part of the Central’s board of directors at some point in 1875, because the February 11, 1876 Boston Traveler includes his name on the slate of directors “re-elected” by the stockholders. Had the Shaker brothers referred to in the May 31st passage been cutting ties under the direction of Pease or Wilcox? The December 24, 1883 Springfield Republican , published just months after Omar’s death, reported the sale of parcels of Shaker timberland by Richard Van Deusen, Omar’’ successor, and recorded that Omar would buy in wood rather than sell it: “Elder Pease would not sell timber, but bought all he could get at a low price. But Elder Van Deusen is selling off the out lots pretty rapidly.”[3]

I put together the information in the two articles and pondered it. Had the men described in the May 31st, 1875 article cut the ties from timber bought in for that purpose by Omar or had they cut down village trees? [4]

I smelled the possibility of some sort of battle or intrigue. Was Omar pressured to leave the board and replaced with Wilcox because Omar was reluctant to cut? The railroad would not have ousted him if he refused to sell. They would just have bought the wood from another source. But could Omar have been pressured to resign by his superiors or his fellow Shakers because they wanted the greater margin of profit arising from cutting down trees on their own property instead of purchasing timber and cutting it for ties? This possibility fascinates me because such an incident would represent Omar’s sudden discovery of a conflict of interest between his traditional role as protector of the Enfield Shakers’ timber resources and his new role in the voracious timber-consuming railroad industry. Such a clash would have resonance with each one of us who is both a consumer of resources and a would-be conservationist.

Photograph of Omar Pease’s pines after being felled by the Hurrican of 1938.

Thinking that such a conflict might have taken place in Omar’s life and hoping that I might find evidence of it in company documents, I turned to the institution where the records of the Connecticut Central Railroad are located—Archives & Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center of the University of Connecticut at Storrs.

The history field is not well-known for being remunerative, and the challenge for me was how I was going to fund this research trip. I was delighted when a call to Archives & Special Collections revealed the existence of the Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz Travel Grants that help pay for researchers’ expenses when they come to use the great resources of the center. I applied and when I received news that I had been awarded one of the grants, I was overwhelmed with gratitude to both the administration and staff of Archives & Special Collections and to Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz for leaving such a wonderful legacy to aid scholarly research. I soon found myself ensconced in a modest, comfortable, and reasonably-priced motel room. It is hard to describe the joy, eager anticipation, and sense of adventure that I felt every day as I traveled to UConn. I could hardly wait to dive into the treasures of the archive!

And what treasures they were. In addition to the ledgers and papers of the Connecticut Central, there were also materials relating to several other railroad companies that were connected to the Central over the years. In addition to ledgers, these items included board of directors’ minutes, bills, receipts, financial statements, cash books, vouchers, legal papers, contracts and agreements. However, as wonderful as these materials are, Archives & Special Collections’ most precious possession is its hugely knowledgeable and incredibly committed staff. In the days that would follow, I would come to know the great courtesy and help of the staff members who man the desk and the graciousness ofMelissa Watterworth Batt, Archivist for Literary & Natural History Collections. I would also benefit from the extremely valuable assistance, guidance, and advice of Laura Smith, Curator for Business, Railroad, Labor and Organizational Collections. All of these individuals go far beyond the call of duty in aiding researchers.

In Archives & Special Collections’ collections I did not find any information that would explain the departure of Omar Pease from the Connecticut Central’s board of directors and his replacement by George Wilcox. But I found so much more! The materials helped me to reconstruct the history of the Connecticut Central Railroad and allowed me to consider how the ups and downs of that history would have impacted the Enfield Shakers as they operated what became known as Shaker Station on the line. Chartered in 1871 and built in 1875, the Central leased itself to the Connecticut Valley Railroad in 1876 but, since the Connecticut Valley soon defaulted on its second mortgage bonds and was quickly placed in receivership, the Connecticut Central Railroad operated as an independent entity until 1880. In that year of 1880 the Central leased itself to the New York & New England Railroad. One of the great discoveries I made at Archives & Special Collections was a copy of this lease agreement. Also greatly helpful were the bound volumes of board of directors’ minutes of the NY & NE. While I am still trying to understand the exact details of the legalities and financial arrangements, in essence it can be said that the New York and New England held the mortgage on the Connecticut Central. When the latter could not make payments, the NY & NE began proceedings to foreclose in 1885. However, the Central mounted a legal resistance that meant the wrangle dragged on until the closing months of 1887. In the years following its gobbling up of the Connecticut Central Railroad, the New York and New England would itself, in turn, be eventually absorbed by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad.

It has long been claimed among Shaker scholars that the railroad that ran through Enfield Shaker Village only carried freight and not people. It primarily did carry freight, and lumber was one of the things it transported. However, the ledgers of the Connecticut Central that I saw at Archives & Special Collections clearly show income from carrying passengers. A notation that I saw later in an outside source shows that the line did not carry commuters (its schedule perhaps not making it convenient for regular travel to and from individuals’ workplaces) but passengers were definitely riding this train.

Sarah H. Gordon says in Passage To Union: “Organizing nationally was the work of the age, and ticketing records show that railroads made possible the growth of organizations with a national membership of people with middling means.” Agricultural, forestry, and conservation organizations mushroomed into existence with the development of the railroad. Archives & Special Collections contains the papers of the Gold family, including those of T.S. Gold, who served for years as the secretary of the Connecticut Board of Agriculture and who belonged to a myriad of such national, regional, and local organizations. While I have yet to find evidence that Omar Pease had an association with any such group, in the Gold collection I found a very interesting letter from Richard Van Deusen, Omar’s successor, to T.S. Gold. It reveals Van Deusen’s involvement in one of these agricultural organizations. Another letter is to Gold is written on Connecticut State Board of Agriculture letterhead and printed on that letterhead is a list of all members of the board in 1884, the year following Omar’s death. This list will enable further research to find out if Pease had contact with any of these men.[5]

Ken Burns, the nation’s foremost maker of historical documentary films, has said that archives, libraries, and museums contain the DNA of our civilization. Archives & Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center is a treasure house that contains a wealth of material that is a precious resource for scholars. I will always have wonderful memories of the time that I spent there and gratitude that such a special place exists. I invite others to discover the historical riches that can be found there.

Darryl Thompson, Shaker historian, spent years at the Canterbury, New Hampshire Shaker village as the sisters there employed his father, Charles “Bud” Thompson. Mr. Thompson has lectured widely about the Shakers, authored articles about them, assisted in the editing of Shaker-related books, taught classes in Shaker history, and has led tours at Canterbury Shaker Village for decades. An American history instructor at the New Hampshire Institute of Art at Manchester, Mr. Thompson has assisted in the research for Ken Burns’ PBS series on World War II and the national parks and was, along with his father, among the consultants used by Ken Burns in his documentary film The Shakers: Hands to Work, Hearts to God (Walpole, NH: Florentine Films, 1984). In 2015, Mr. Thompson was awarded a Strochlitz Travel Grant from Archives and Special Collections at the University of Connecticut to support his ongoing research.

Sources cited:

[1] Sarah H. Gordon, Passage to Union: How the Railroads Transformed American Life, 1829-1929 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, Publisher, 1997), 106; Sherry H. Olson’s The Depletion Myth: A History of Railroad Use of Timber (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1971), 4. 10, 12 [Table 1: ”Crosstie estimates, 1870-1910”].

[2] Eric Rutkow, American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, New Delhi: Scribner, 2012), 130.

[3] “East Longmeadow “ column, “Hampden County News” section, Springfield Republican (Springfield, Massachusetts), December 24, 1883, 6.

[4] “Annual Meetings. Connecticut Central Railroad…,”Boston Daily Advertiser (Boston, MA), Thursday, February 6, 1873 (Issue 32), 2, column c; “Railroad Matters. New Lay-Out of the Connecticut Central in Enfield—Recovery of Commissioner Northrop—Election,” Saturday, February 20, 1875, Connecticut Courant (Hartford, CT), Vol. 111, Issue 8, 4; “Connecticut” column, Springfield Republican, Monday, May 31, 1875 pg. 6;“Springfield and Vicinity,” column in “Local Intelligence” section, Tuesday, July 6, 1875, Springfield Republican (Springfield, MA), 6; “Railroad News,” Friday, February 11, 1876, Boston Traveler (Boston, MA), 1.

[5] Sarah H. Gordon, Passage To Union: How the Railroads Transformed American Life, 1829-1929 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, Publisher, 1997) , Pg. 181.

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot.

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot. Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.

danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.

family’s

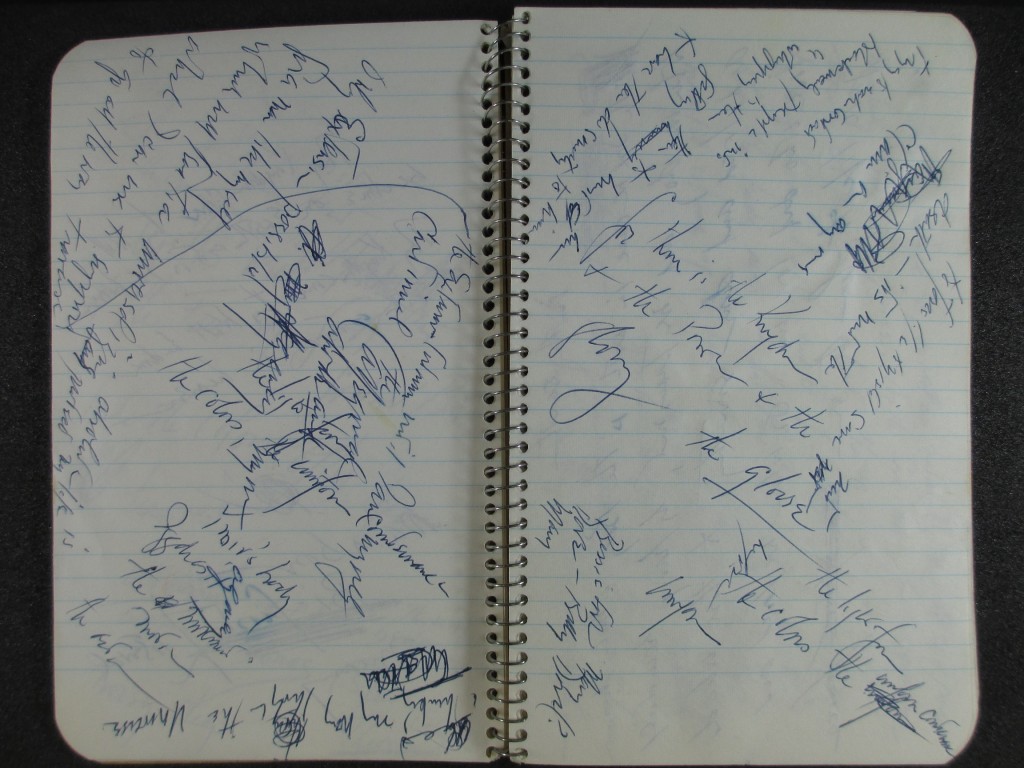

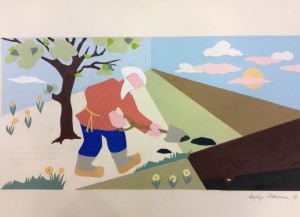

family’s  change in fortune and status, they moved east, to Harbin, and then, via Vladivostok, to the United States. The readjustment to their diminished financial situation was the beginning of her fashion design career – helping her mother sew dresses for clients in Harbin. Throughout her life, Esphyr (whose friends called her Phyra) would sew and consult on fashion and home décor to supplement her income, just as she did with children’s books (in amongst her papers in Box 13 are two experimental fabric children’s books; an attempt at combining her two skills). Slobodkina kept scrapbooks, using large binders of wallpaper samples as her medium. Here, along with dummies for greeting cards, sketches, reviews, letters from children thanking her for her books, fashion design [Fig. 3], the peddler from Caps for Sale interacts with Slobodkina’s “poodies” from her very first children’s book attempt – Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 4]. In these scrapbooks, then, Slobodkina’s various artistic and commercial endeavors combine and interact. Unlike her biographers, perhaps, she did not segregate her work into compartments.

change in fortune and status, they moved east, to Harbin, and then, via Vladivostok, to the United States. The readjustment to their diminished financial situation was the beginning of her fashion design career – helping her mother sew dresses for clients in Harbin. Throughout her life, Esphyr (whose friends called her Phyra) would sew and consult on fashion and home décor to supplement her income, just as she did with children’s books (in amongst her papers in Box 13 are two experimental fabric children’s books; an attempt at combining her two skills). Slobodkina kept scrapbooks, using large binders of wallpaper samples as her medium. Here, along with dummies for greeting cards, sketches, reviews, letters from children thanking her for her books, fashion design [Fig. 3], the peddler from Caps for Sale interacts with Slobodkina’s “poodies” from her very first children’s book attempt – Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 4]. In these scrapbooks, then, Slobodkina’s various artistic and commercial endeavors combine and interact. Unlike her biographers, perhaps, she did not segregate her work into compartments.

pasted in the aforementioned scrapbook [Fig. 6]. Preserved under plastic wrap, the image not only makes emphatic the link between handiwork and art, but also is penetrated by the impish Poodies. Slobodkina, in an interview, relates that the inspiration for the book came from a story she heard being told by the teacher of her sister-in-law’s child, and because of this ambiguous authorship, that William Scott had been hesitant to publish it. On the advice of Bertha Mahoney (of The Horn Book), Esphyr gave the peddler a name, and developed the plot more, whereby it was published by Harper Collins (1940) under the editorship of Ursula Nordstrom, and then later by Scott.

pasted in the aforementioned scrapbook [Fig. 6]. Preserved under plastic wrap, the image not only makes emphatic the link between handiwork and art, but also is penetrated by the impish Poodies. Slobodkina, in an interview, relates that the inspiration for the book came from a story she heard being told by the teacher of her sister-in-law’s child, and because of this ambiguous authorship, that William Scott had been hesitant to publish it. On the advice of Bertha Mahoney (of The Horn Book), Esphyr gave the peddler a name, and developed the plot more, whereby it was published by Harper Collins (1940) under the editorship of Ursula Nordstrom, and then later by Scott.

For my final blog post of my summer internship, I want to touch on something that’s been nagging at me ever since I began my work.

For my final blog post of my summer internship, I want to touch on something that’s been nagging at me ever since I began my work.