The UConn Archives & Special Collections podcast d’Archive will release it’s 50th episode on April 24th, 2023 with a live broadcast at 10am EST on 91.7fm WHUS. Beginning in August of 2017, the Archives staff began expanding its outreach program to the airwaves by training on sound engineering and radio protocols in order to effectively bring its collections to new audiences. Since then the radio program and podcast has featured weekly episodes drawing from countless collections held by the Archives & Special Collections and amplifying the expertise of over 60 collaborators ranging from past and present archives and library staff, artists, journalists, curators, faculty, graduate and undergraduate students, high school students, visiting fellows and international students, activists, alumni, collectors and donors, family, and friends.

Continue readingCategory Archives: From the Researcher’s Prospective

James Marshall the Educator: Audio Cassette Lectures at UConn, 1976-1990

The following guest post is by K-Fai Steele, recipient of the 2019 James Marshall Fellowship. K-Fai (www.k-faisteele.com) is an author and illustrator who grew up in a house built in the 1700s with a printing press her father bought from a magician. She wrote and illustrated A Normal Pig. She illustrated Noodlephant by Jacob Kramer (a Kirkus Best of 2019 picture book) and Old MacDonald Had a Baby by Emily Snape. She also illustrated the forthcoming Probably a Unicorn by Jory John and Okapi Tale, the sequel to Noodlephant. She was a Brown Handler Writer in Residence at the San Francisco Public Library, and the 2018 Ezra Jack Keats/Kerlan Memorial Fellow at the University of Minnesota. K-Fai lives in San Francisco.

The job of a professional children’s book author and illustrator is challenging. There’s no one formula for, or definition of success. The job walks the line between commercial and creative disciplines and requires a bizarre combination of skills: not only writing and illustrating books but being able to perform in front of large varied audiences (toddlers one day, fifth graders the next), deftness at publicity and social media, teaching, and generally being able to project an aura of success and expertise. It can often feel competitive and lonely. And one is paid as a freelancer, so (at least in the United States) there is no economic safety net and it’s hard to plan for a long term career. Another aspect of the job requires constant learning, growth, and improvisation which can either be stressful or exciting and luxurious (if you have the time and space to fully devote to it). Whenever I feel stuck I end up in a library and I’ve learned that some of the best libraries and collections contain public collections of children’s literature preliminary materials. The University of Connecticut is one of these places, and through the James Marshall Fellowship I was given the time, space, and funding to spend time learning and luxuriating in their collection.

If you spend enough time with someone’s work you get a sense of their process; in a way it’s the closest thing you can get to a mentorship. In his essays Caldecott & Co.: Notes on Books and Pictures, Maurice Sendak quotes Alphonse Mucha (a mentor to one of Sendak’s heroes Winsor McKay, the creator of the Little Nemo comic): “I think it would be wise for every art student to set up a certain popular artist whom he likes best and adapt his ‘handling’ or style… when you are puzzled with any part of your work, see how it has been handled by your favorite and fix it up in a similar manner.” It’s a very clever way to get a very good (and free) education.

When you read a picture book you only see the finished product. When you visit archives, you see evidence of an often messy process, from sketches and sketchbooks to drafts, manuscripts, and original art. Occasionally you find very special pieces of media, like collections of audio cassette lectures. Francelia Butler was a professor of Children’s Literature at UCONN from the 1960s to 1990s and she invited dozens of authors, performers, and otherwise impressive thinkers to speak in her Children’s Literature 200 class, or as students referred to it, “kiddie lit 101.” She had the foresight to record most of these lectures which are now housed in the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection. James Marshall lived a couple of miles from the UCONN Storrs campus and would give a yearly lecture to her class of primarily undergraduates from 1976-1990 when he was 34 to 48 years old (he died when he was 50). These lectures are mostly off the cuff; he reads a book aloud (often George and Martha or The Stupids), discusses how he came up with ideas for books like Miss Nelson, then takes questions from the audience.

Marshall is the perfect guest lecturer. He is funny, insightful, knows how to work a crowd, and best of all he’s a generous lecturer. He knows how to communicate ideas and make them accessible. At his core he was an educator; he worked professionally as one for a while, having taken over Maurice Sendak’s picture book making class at Parsons. Much of the insights he shares in these recorded lectures are still deeply relevant today, particularly in terms of the creative process and the job of a children’s book creator. Marshall agonized about writer’s block and felt the pressure to make money. He also spoke from the perspective of an outsider who worked extremely hard and never took the joy of making books for granted.

When I arrived at UCONN to start my fellowship I didn’t anticipate that most of my time would be spent using my ears rather than my eyes. I had spent three weeks in 2018 at the Kerlan Collection looking through dozens of his sketchbooks in their collection and since then have tried to read all of his books. I realized I was engaging in a bit of detective work, trying to put the pieces together of a fascinating, talented, funny creator through the crumbs he left behind. Hearing him talk about his work (getting a firsthand narrative) made me feel incandescent. I popped in one cassette after another and was grateful for my fast typing (as of the time of this blog post’s publishing only two of the cassettes have been digitized; according to the archivist it’s an expensive and laborious process). In this post I’m going to share some quotations from these audiocassettes, what surfaced for me as a picture book creator, and what I think other people in the field might find interesting, from his process to how he thought about creative work.

“I start off drawing. I develop a character, make it as crazy as I can, and put that character in a situation. I start with a visual. I couldn’t sit at a typewriter and start a story with words… Drawings first, and then I type it up” (1977, cassette 504). Marshall was known for his strong characters; consider George and Martha, Fox, or The Stupids; the story revolves around them and how they interact with other characters. It’s not so much about plot; Marshall at one point describes George and Martha as a comedy of manners. “I teach my kids at Parsons that to start out you must have a very solid rounded character that lives. I have lots of sketchbooks and I just develop characters as they go along” (1982, cassette 515). Marshall trusted that a good story would organically come out of a good character, particularly if put in an interesting situation where they have to react. There’s a sort of faith required in starting with a character; you don’t know who’s going to show up on the page. You get to know a character by the way they look, their gesture, and how they react to other characters.

Marshall didn’t discuss a specific method that he used to generate stories because he didn’t seem to have one. He described working intuitively, relying on his brain and hand to put together funny ideas. “People ask me often where the ideas come from. If I knew that I could probably spell it out to you… I don’t know where the good stuff happens. It happens when I work a lot, and late at night. Usually If I’ve been working 8-10 hours doing just mechanical stuff I’m so tired all my defenses are down. I’m not worried whether it’s going to be a success or not, and some nutty idea comes in, it’s like someone else told me that… You know it came from inside your head but you don’t know why or how” (1979, cassette 506). “What I do is try to sit down, and if I fall down and start laughing that’s a good sign” (1980, cassette 508). It seemed that he didn’t examine his story-making because he was worried that if he figured it out he would lose the muse. “What I do is intuitive and I don’t know why I’m sitting here talking to you because I don’t really know why I do what I do, and to talk about it is a little scary to analyze it. I’m afraid if I look at it too much and try to figure out what I do it’ll go away” (1985, cassette 525). Since he relied so heavily on intuition his fear of losing the muse makes sense. He mentioned this fear in several lectures, and it seems to really be the thing he feared the most: the bucket going down the well and coming up dry.

Perhaps this fear came from a sense of what we would now describe as imposter syndrome. “Often I have so much trouble coming up with endings. It’s just like hell. Because you think here I am, this is what I do for a living, but maybe I’m not so good anymore, maybe I never had any talent in the first place” (1987, cassette 527). Marshall continues in a 1990 lecture, “I’ve thrown up in my studio from the fear of thinking I’m all finished, I’m washed up, I have no talent, I can’t even write one of these dumb books, I can’t think of another joke” (cassette 531).

Perhaps it came because making good books for children is deceptively challenging. There isn’t a roadmap, particularly when you’re making something that pushes boundaries of humor, style, etc. “When I’m drawing it’s like heaven, even when it’s not going so well I’m really, really happy. I feel connected, I feel like I belong. Why it’s such hell to get started, I don’t know. I guess it’s because I’m scared. Chekhov had the same feeling, he thought he was no good, couldn’t cut it. If a guy that great can have those feelings maybe it’s not so abnormal, maybe you should have those feelings of insecurity. Because if you’re absolutely sure that what you’re doing is brilliant what you’re doing is copying yourself or copying someone else” (1988, cassette 529).

Or perhaps the pressure was more external; he needed to make more books in order to keep his career (and income stream) flowing. This is when his practice of writing intuitively probably chafed against a demanding publishing schedule. “I have an artistic problem: when a book is successful, editors like to see success perpetuated, so they hire you to do a sequel. I’ve done so many sequels but I haven’t gotten any quite right. It’s the hardest thing in the world to capture the spirit of another book when you don’t have an idea. I’m doing three picture books, all three are sequels, and I’m stalled on all three. It’s a sickening feeling to think that you’re going to have to turn that money back and that you’ve run out of ideas” (1985, cassette 525). Marshall’s output was prodigious; he made around eighty picture books during his 50-year life. What is the result of working faster than your machine wants to run? The quality may suffer, at least in the creator’s eyes. In one lecture Marshall says, “I’ve made 60 books and only about 20 am I really proud of” (1983, cassette 517).

Marshall’s writing and drawings have a sense of lightness and ease to them, particularly in the way he draws characters and communicates their emotions through their eyes (often simple dots). In 1997 several years after Marshall’s death, Sendak wrote in the New York Times, “Much has been written concerning the sheer deliciousness of Marshall’s simple, elegant style. The simplicity is deceiving; there is richness of design and mastery of composition on every page. Not surprising, since James was a notorious perfectionist and endlessly redrew those ”simple” pictures.”

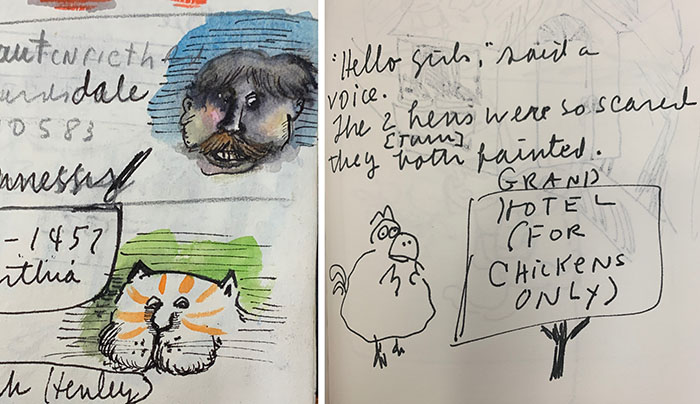

Marshall drew with joy, and this is most evident in UCONN’s collection of his sketchbooks. In his lectures he talks about the phenomenon I hear a lot of other author-illustrators experiencing when they move from sketches to final art; some freshness is lost. “It’s when you have to prepare something that’s going to get published, at least not only me but everyone I know in the business, you get tense and frightened because this is going to be out there, there are going to be 20,000 copies of this, and it gets tighter and tighter. The best stuff I’ve done of any quality is in my sketchbooks and I pick that stuff out and I’m like why can’t I do that here?” (1984, cassette 520). Perhaps it’s different when you’re making final art because you know that you have an audience, that you’re relying on the art to make money. It’s less about amusing yourself; it goes from a private activity to a very public one. “The sketches are so much more interesting, that’s the fun part. It’s when you do a line that you know is going to be published you start to clutch and tighten up. I’m just now learning to do books and get a line that’s going to be published that’s as good as the one in the sketches. I’d love to take my old sketches out and publish them. I feel so much more comfortable with them. I don’t know if it’s a fear of success or fear of failure, it’s a really terrifying process to go through” (1981, cassette 511).

Marshall also shared insights into how he thought he was perceived by gatekeepers of the industry, specifically librarians who had a more traditional sense of illustration and who also reviewed books and selected for awards (in particular the Caldecott Award). “I work in basically creative periods of about 3 weeks that’s all I can stand… This is dangerous because when I tell librarians (“conventional people”) if I tell them how short it takes me to do a book I can see in their eyes my stock going down. You have to tell them you worked 5 years on this book and you’ve drawn with the blood of your slaughtered children and then it’s a masterpiece” (1985, cassette 519) Marshall drew somewhat injured and bitter conclusions about why he had been overlooked, “People who are in children’s books are ashamed of being in children’s books. People on committees want to pick a book that shows they’re an important, art-minded profession” (1985, cassette 519).

Sendak wrote that Marshall “paid the price of being maddeningly underestimated — of being dubbed ”zany” (an adjective that drove him to murderous rage)… he was dismissed as the artist who could — or should or might — do worthier work if he would only dig deeper and harder. The comic note, the delicate riff were deemed, finally, insufficient. James knew better, of course, and he was right, of course, but he suffered nevertheless. There was nothing he could do to impress the establishment; that was his triumph and his curse. Marshall did fulfill his genius, and its rarity and subtlety confounded the so-called critical world. The award-givers were foolish enough to consider him a charming lightweight, and when Caldecott Medal time came around, they ignored him again and again.” Marshall also spoke about competition in the children’s literature world, which undoubtedly was connected to him not feeling appreciated, validated, or celebrated by the people who held power. “The world of children’s books I used to say is a nice world. It is not, it’s a nest of vipers, we all hate each other… we’re very competitive” (1982, cassette 513).

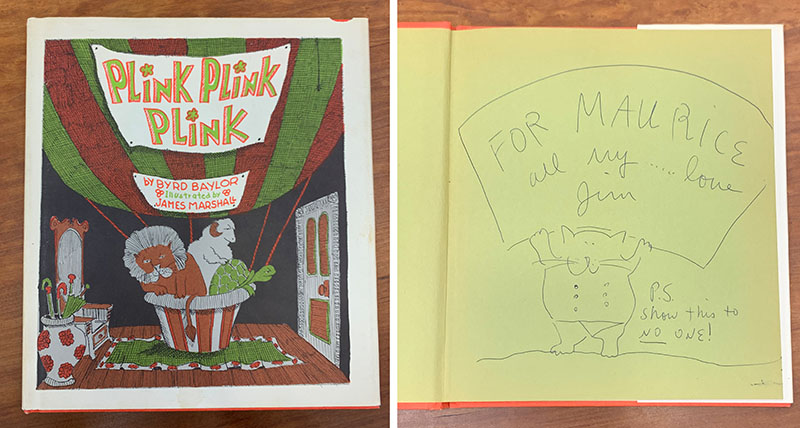

It was interesting to hear Marshall talk about the other authors and illustrators he was in community with. In nearly every lecture he named some of the people who he thought were doing the best work in children’s literature: Arnold Lobel, Edward Gorey, Maurice Sendak, Tomi Ungerer, Rosemary Wells, William Steig, Edward Ardizzone, and Quentin Blake were all mentioned. “If you want to see some magnificent small jewels, look at the Frog and Toad books. I thought, oh I can do that. First I saw Sendak: oh, I can do that. Lobel: oh I can write stories about two friends too. They sort of gave me confidence. I didn’t know how hard it is. Sometimes it’s fun, sometimes it’s impossible to try and write two-page stories with a beginning, middle, and end” (1990, cassette 532). He clearly adored Maurice Sendak, who he referred to as “the granddaddy of us all” (1980, cassette 508) in terms of contemporary illustration. The Maurice Sendak Collection of James Marshall at UCONN contains several of Marshall’s books that he inscribed for Sendak, including a rare copy of his first illustrated book, Plink, Plink, Plink (1971) by Byrd Baylor which Marshall said “sunk, sunk, sunk” due to the “awful poems and awful pictures” (1977, cassette 504).

This collection of recordings is a very rare and special item; you just don’t find a lot of authors speaking in their own words, at length, about their work. I think that this speaks to Marshall’s experience as an educator; someone who has good communication skills, a sense for what might be interesting content, respect for their audience, a willingness to be generous with the knowledge they possess, and their love for the work.

One of my favorite things that Marshall said had to do with the joy of getting to do the thing you love most in the world as a job. “To be able to support myself by doing what I really like to do best and by being creative, I never dreamed that that could be. I was raised with protestant puritant [sic] ethics. In Texas you had to bring home the bacon by doing stuff that you hated; my daddy hated his job, my mama hated being a housewife, everyone in my family hated everything. I thought when I became an adult I had to just swallow it. It’s not true. It’s a wonderful, wonderful feeling” (1983, cassette 517). This is something that you can easily lose sight of a children’s book maker as you get involved in the day-to-day of trying to meet deadlines, negotiate with art directors, redo cover art, schedule school visits, make money and budget wisely, etc. I’m writing this blog post in late spring 2020 in the midst of a global pandemic which has made clear that nothing is guaranteed, in particular human life, especially those most vulnerable in our society. For a while I wasn’t sure if books or art even mattered. But of course they do, and the act of engaging in joyful creative work is a much-needed lifeline, as Marshall attested to during his short life, ended by the HIV/AIDS pandemic in 1992. “One of the most wonderful things in the world is to do creative work, it is the greatest high, it makes your life come together” (1987, cassette 527).

Teaching Activism and Leadership through Archives

The following guest blog post was written by Laura Wright, PhD candidate in UConn’s English Department and first-year writing instructor as well as excerpts from students in her 2016 English 1010S seminar.

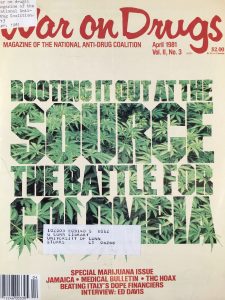

Building towards the Presidential Election in November 2016, Students in ENGL 1010S: Seminar in Academic Writing considered different definitions of “leadership.” The final project asked students to think critically about leadership historically through particular artifacts from the Archives & Special Collections Alternative Press Collection and Bread and Puppet Theater holdings. In one class session, Graham Stinnett, the Curator of Human Rights Collections and Alternative Press Collections, provided an overview of materials and their historical contexts. During this session, students learned about radical movements on UConn’s campus and how materials from these movements arrived in the Dodd Center. The collections students observed encompassed a range of media, including Alternative Press newspapers, like The Rat and Rising Up Angry, as well as performance programs and promotional materials from the Bread and Puppet Theatre.

Building towards the Presidential Election in November 2016, Students in ENGL 1010S: Seminar in Academic Writing considered different definitions of “leadership.” The final project asked students to think critically about leadership historically through particular artifacts from the Archives & Special Collections Alternative Press Collection and Bread and Puppet Theater holdings. In one class session, Graham Stinnett, the Curator of Human Rights Collections and Alternative Press Collections, provided an overview of materials and their historical contexts. During this session, students learned about radical movements on UConn’s campus and how materials from these movements arrived in the Dodd Center. The collections students observed encompassed a range of media, including Alternative Press newspapers, like The Rat and Rising Up Angry, as well as performance programs and promotional materials from the Bread and Puppet Theatre.

For this project, students argued for the relationship between activism and leadership represented in these particular collections. Rather than writing a research paper, students compiled dossiers of material, using their unique artifacts as a jumping off point for further research. Students offered a detailed interpretation of the archival material, located it in a larger historical narrative, researched peer-reviewed sources for an annotated bibliography, and wrote a short essay putting all their materials into conversation with one another. Continue reading

Finding the Artist in His Art: A Week with the James Marshall Papers

By Julie Danielson

James Marshall (called “Jim” by friends and family) created some of children’s literature’s most iconic and beloved characters, including but certainly not limited to the substitute teacher everyone loves to hate, Viola Swamp, and George and Martha, two hippos who showed readers what a real friendship looks like. Since I am researching Jim’s life and work for a biography, I knew that visiting the James Marshall Papers in Archives and Special Collections at the University of Connecticut’s Northeast Children’s Literature Collection would be tremendously beneficial. In fact, Jim’s works and papers are also held in two other collections in this country (one in Mississippi and one in Minnesota), which I hope to visit one day, but I knew that visiting UConn’s Archives and Special Collections  would be especially insightful, since Jim made his home there in Mansfield Hollow, not far at all from the University. Indeed, I spent my evenings, as I wanted to maximize every possible moment during my days for exploring the collection, talking to people there in Connecticut who knew and loved Jim, including his partner William Gray, still living in the home they once shared.

would be especially insightful, since Jim made his home there in Mansfield Hollow, not far at all from the University. Indeed, I spent my evenings, as I wanted to maximize every possible moment during my days for exploring the collection, talking to people there in Connecticut who knew and loved Jim, including his partner William Gray, still living in the home they once shared.

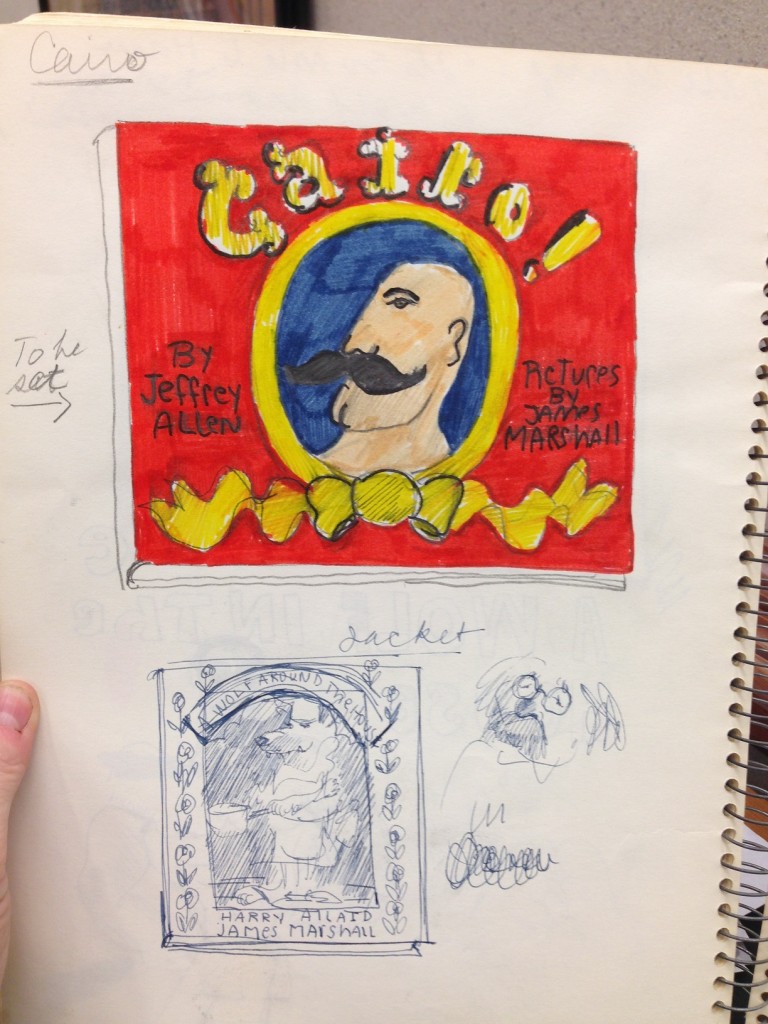

The collection is vast and impressive, just what a biographer needs. I had five full days, thanks to the James Marshall Fellowship awarded to me, to explore the archives and see, up close, many pieces of original artwork, as well as a great deal of his sketchbooks. I saw manuscripts, sketches, storyboards, jacket studies, character studies, preliminary drawings, dummies, proofs, original art, and much more from many of Jim’s published works, including a handful of his early books — It’s So Nice to Have a Wolf Around the House, Bonzini! The Tattooed Man, Mary Alice, Operator Number 9, and more. To see sketches and art from his earlier books was thrilling, because I’m particularly fond of many of those titles. (Bonzini!, I learned in the sketchbooks, was originally titledCairo.) Also on hand in the collection are sketches and art from his more well-known books, as well as books published at the end of his career (he died in 1992), including the popular George and Martha books and Goldilocks and the Three Bears, which received a 1989 Caldecott Honor. Read more…

Eleanor Estes: Chronicler of the Family Story

by Claudia Mills

I came to Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center on a mission, as an avenging angel, if you will. My self-imposed charge: to defend an author I loved as a child, and continue to love, from criticism of her work that I felt was mistaken, or at least misguided.

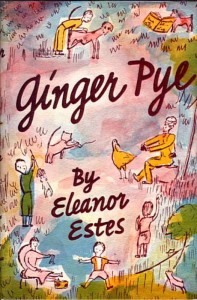

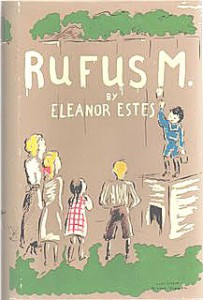

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot.

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot.

The two books about the Pyes (Ginger Pye and Pinky Pye) differ notably from the three earlier books about the Moffats in shifting from an episodic format to a plot structure built around a single, unifying dramatic question, in both cases involving the solving of a mystery. Who stole the Pyes’ dog Ginger Pye? What happened to the little owl lost at sea that ends up becoming Owlie Pye? In both books, the solution to the mystery is extremely obvious, with insistent foreshadowing of the ultimate resolution and blatant, repetitive telegraphing of every clue. This has been widely regarded by adult critics as unsatisfying.

Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

But as I read these two books, Estes isn’t trying and failing to provide a suspenseful mystery. Instead, both books can be read as positively cautioning readers against traditional storytelling techniques, with their “dramatic build-up” and “logical progression toward climax.” Read carefully, both books suggest that suspenseful storytelling can be actually dangerous, its risks greater than its rewards. Estes shows her characters themselves engaging in sensationalist, overly dramatic storytelling with near-disastrous results: for the missing owl (in Pinky Pye) and missing dog (in Ginger Pye. As Papa insists upon theatrical revelation of the discovered location of the little owl, he prolongs the telling of the story to such an extent that the owl is meanwhile endangered by the predatory kitten; as Jerry and Rachel Pye fashion a sensationalist account of Ginger’s kidnapping by an “unsavory character,” they misdirect the police and fail to notice the actual, far more humdrum, culprit. Both books, then, contain within themselves material for a critique of exactly the kind of suspenseful fiction Estes is chided for not providing.

I wondered, however, if Estes herself would share my reading of her books. Perhaps the critics were correct, and she tried and failed to provide more satisfying suspense. Or perhaps I was correct, and her philosophy of storytelling pointed her in a very different direction.

So I spent an enchanted week the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center examining Eleanor Estes’s papers – drafts of speeches she gave throughout her career and extensive editorial correspondence from Ginger Pye’s editor, the legendary Margaret McElderry – in search of support for my claims that Estes did not try and fail to provide suspenseful storytelling in her Pye books, but chose not to do so because of her commitment to a different way of engaging with young readers.

So I spent an enchanted week the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center examining Eleanor Estes’s papers – drafts of speeches she gave throughout her career and extensive editorial correspondence from Ginger Pye’s editor, the legendary Margaret McElderry – in search of support for my claims that Estes did not try and fail to provide suspenseful storytelling in her Pye books, but chose not to do so because of her commitment to a different way of engaging with young readers.

And find it I did.

The collection contains, for the most part, only letters sent to Estes from her editors, rather than letters by Estes herself, so scholars have to read between their lines to recover what Estes must have written to provoke these replies. I learned that Estes apparently considered not resolving the mystery of Ginger Pye’s disappearance at all! McElderry writes to her, as the work is in progress, “Not having read any of it, it is a little difficult to say anything about the problem of who stole him, but I am inclined to agree with you that children reading the book would probably want to know who the culprit is.” McElderry also writes to reassure Estes that certain scenes are not too frightening for children: “I can well imagine the qualms that any author feels at this point but I am perfectly sure you should have none of them. The tramp chapter isn’t the least bit too scary, for look what our modern children have become used to from the radio, television, and the movies. And I expect children will always try to climb rocky cliffs whether they read about it first or not, so that you will not be held responsible for any bruises or cuts.” Indeed, Estes’s lack of interest in traditional plot was so great that in a speech to the Onondaga Library System, she admitted, “Sometimes I write a whole book first, like The Moffats, and then put the plot in.”

The clearest answers to my questions about Estes’s literary method came in Box 16, Folder 201, which contained a sheaf of 4 x 6 index cards with handwritten answers to interview questions for a talk at Albertus Magnus College in 1973. In response to the query “Do you think that violence in children’s literature can psychologically damage a ‘normal’ child?” she first problematizes the whole idea of a “normal child,” noting that children have a wide range of sensitivities; she then confesses that she was one of the more sensitive, who tended “to shy away from extreme violence in life, and on the screen and stage. Even not look when the bad man came on.” She goes on to say, “I am not an escapist. But in books for children . . . I don’t see the necessity of depicting life as it really is.” For Estes, then, it was permissible, even commendable, to prioritize comfort over  danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.

danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.

Of course, along the way I found much, much more. What a window into a now-vanished world of publishing is provided by the yellow Western Union telegram from Margaret McElderry with its all-caps shout of joy: CHEERS FOR GINGER. SEND EXPRESS IN BOX. INTEREST AT BOILING POINT. LOVE MARGARET.

Struggling writers may be cheered to know that Estes, now working for the New York Public Library, showed the manuscript of The Moffats to her supervisor, the formidable Miss Anne Carroll Moore before whose pronouncements authors and editors trembled, only to receive this sole comment: “Well, Mrs. Estes, now that you have gotten this book out of your system, go back to being a good children’s librarian”! (Estes reports that Miss Moore had earlier found it difficult to forgive her for marrying fellow librarian Rice Estes: “she did not like her children’s librarians to get married.”) Once Ginger Pye received the Newbery Medal, however, a friend of Estes’s wrote to her of Miss Moore’s quite different public account of their relationship: now Estes had “risen to the top in the esteem of Annie Carolly Moorey. This great friend through all your struggling years, this inexhaustible dealer-outer of encouragement, has finally had her judgment vindicated. I nearly vomited.”

And then there were the pages of scribbled notes with their wonderful revelation of how Estes gathered her ideas in wandering, random bursts of creativity:

Once when I was a dog

A Lion I knew

The story of the pants

These are not the notes of someone who prioritizes the construction of tightly ordered plots, but someone who celebrates the shifting, fragmented way that children look upon and inhabit the fleeting world of childhood.

Claudia Mills is Associate Professor emerita in the Philosophy Department at the University of Colorado at Boulder and a frequent visiting professor at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana. Most of her essays on children’s literature explore ethical and philosophical themes in children’s books. She is also the author of over fifty books of her own for young readers, including most recently The Trouble with Ants (Knopf, 2015, launch title of the Nora Notebooks series about a girl who wants to grow up to be a myrmecologist) and Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee champ (Farrar, 2015, the fourth book in the Franklin School Friends series). Claudia Mills is a 2015 recipient of the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant.

Notes:

[1] Townsend, John Rowe. “Eleanor Estes.” In A Sense of Story: Essays on Contemporary Writers for Children. Philadelphia and New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1971: 79-85.

[2] Wolf, Virginia L., “Eleanor Estes,” in American Writers for Children, 1900-1960, ed. John Cech, Detroit: Gale, 1983: 146-56.

Esphyr Slobodkina – Modernist (Children’s Book) Illustrator/Author

by JoAnn Conrad, Recipient of the 2015 Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant

Part of my ongoing research into children’s picturebooks of the mid-twentieth century has to do with the ways in which the work of illustrators has insinuated itself into the public memory even as the names of individual artists may be relatively obscure. This is the case with the rare female artist and, particularly, Esphyr Slobodkina, as her influence is inversely proportional to the obscurity of her name. “Esphyr Slobodkina . . .helped pave the way for the acceptance of abstract art in the United States and translate[d] European modernism into an American idiom.”[1]

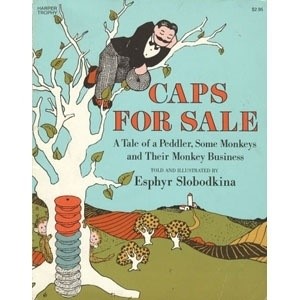

A simple and serendipitous anecdote demonstrates this: While researching her papers at UConn’s Archives and Special Collections this summer, I was living across the street from the UConn Bookstore. One day, I noticed a display in the window announcing “Caps for Sale” [Fig. 1], clearly alluding to one of Slobodkina’s most popular books of the same name [Fig. 2]. The power of the sale poster derives from and depends on the reference to the book, which is assumed to be automatic.

There is a fair amount about Slobodkina’s life and work available. The Finding Aid for the Slobodkina Papers at Archives and Special Collections provides a brief biography as does the website of the Esphyr Slobodkina Foundation. The 2009 Rediscovering Slobodkina: A Pioneer of American Abstraction includes information on her life as well as her contributions to the art world, but the full biography has yet to be written. Esphyr Slobodkina anticipated that it would be written, however, and drafted a comprehensive, detailed, 5-volume manuscript “Notes for a Biographer” which resides in her papers. The Slobodkina Papers contain much more than is in her books – things that would never be published but which give a researcher like me access to insights into the thoughts and motivations of the artist. One of the pleasures of this kind of archival research is not only this intimate and personal connection one makes across time, but also the unexpected revelations into the personality of the artist that informs her work. My intention here is to provide some of those “off the books” glimpses into the work and person – Esphyr Slobodkina.

Esphyr Slobodkina was born to a wealthy Russian-Jewish family in Russia before the Revolution. Continue reading…

Emily Arnold McCully gets a new finding aid

A new finding aid is now available for the Emily Arnold McCully Papers. The collection consists of sketches, dummies, research materials and artwork for eight of her books: The Taxing Case of the Cows, the Divide, Old Home Day, Ballot Box Battle, Ballerina Swan, My Heart Glow, Secret Seder, and The Helpful Puppy. Emily Arnold McCully, an American writer and illustrator, won the Caldecott Medal for U.S. picture book illustration in 1993, for Mirette on the High Wire which she also wrote.

She was born in Galesburg, Illinois, in 1939, and grew up in Garden City, New York. She attended Pembroke College, now a part of Brown University, and earned an M.A. in Art History from Columbia University. At Brown she acted in the inaugural evening of Production Workshop and other plays, co-wrote the annual musical, Brownbrokers, and earned a Phi Beta Kappa key.

In 1976, she published a short story in The Massachusetts Review. It was selected for the O’Henry Collection: Best Short Stories of the Year. Two novels followed: A Craving in 1982, and Life Drawing in 1986. In 2012, Ms. McCully published Ballerina Swan with Holiday House Books for Young People, written by legendary prima ballerina Allegra Kent. It has received rave reviews from The New York Times, Kirkus Reviews, and School Library Journal and was praised in the “Talk of the Town” column in The New Yorker.

As an actor, she performed in Equity productions of Elizabeth Diggs’ Saint Florence at Capital Rep in Albany and The Vineyard Theater in New York City. In addition to the Caldecott Award, Ms. McCully has received a Christopher Award for Picnic, the Jane Addams Award, the Giverney Award and an honorary doctorate from Brown University.

Book Launch for Dr. Katharine Capshaw

Civil Rights Childhood: Picturing Liberation in African American Photobooks (University of Minnesota Press).

Dr. Capshaw’s latest book, Civil Rights Childhood: Picturing Liberation in African American Photobooks was published by University of Minnesota Press in 2014. In it Dr. Capshaw “…draws on works ranging from documentary photography, coffee-table and art books, and popular historical narratives and photographic picture books for the very young.” (http://generalbooks.bookstore.uconn.edu/event/book-launch-katherine-capshaw). Please join us on Wednesday, March 25, 2015 at 4:00pm at the UConn Co-op Bookstore, One Royce Circle, 101 Storrs Center, Storrs, CT 06268. For more information call 860-486-8525.

Hilary Knight on HBO tonight

At 9pm on March 23, 2015, HBO will present a documentary produced by Lena Dunham, titled It’s me, Hilary: the Man who Drew Eloise, in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the first Eloise book. Lena Dunham, now 28, bears a tattoo of Eloise that is visible at times during her appearances on the HBO show Girls, so Hilary Knight sent her a signed book and a letter asking Ms. Dunham to share Indian food with him. The rest, as they say, is history. Read the full LA Times story. The Northeast Children’s Literature Collection holds some of Mr. Knight’s archival papers. Don’t miss the show tonight at 9pm.

Unpublished Seuss manuscripts rediscovered

Random House announced yesterday that it will publish What pet should I get? which features the brother and sister from One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish. The manuscript and sketches were found in a box along with the original materials for at least two other books. Random House will announce the publication dates for the other new releases later.

Dr. Seuss’s widow, Audrey Geisel, set the box aside after her husband’s death in 1991, during a renovation of their home. She and a longtime friend recently rediscovered the box, explaining in a statement to Random House: “Ted always worked on multiple projects and started new things all the time — he was constantly drawing and coming up with ideas for new stories.”

ABC’s Good Morning America announced the story this morning as well as USA Today.

What fantastic news for fans of Dr. Seuss.

Dr. Kate Capshaw launches new book

Civil Rights Childhood: Picturing Liberation in African American Photobooks (University of Minnesota Press).

From Cathy J. Schlund-Vials, Ph.D., Director, Asian and Asian American Studies Institute Associate Professor of English and Asian/Asian American Studies:

On February 12, 2015 (at 4 PM) the UConn Co-op (in Storrs Center) will be hosting a book launch for Kate Capshaw’s recently published book, Civil Rights Childhood: Picturing Liberation in African American Photobooks (University of Minnesota Press). What follows is a brief description of the book and a link:

Civil Rights Childhood explores the function of children’s photographic books and the image of the black child in social justice campaigns for school integration and the civil rights movement. Drawing on works ranging from documentary photography and popular historical narratives to coffee-table and art books, Katharine Capshaw shows how the photobook-and the aspirations of childhood itself-encourage cultural transformation. (https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/civil-rights-childhood)

Dr. Katharine Capshaw

This event is sponsored and hosted by the University Co-Op. For more information, please feel free to contact Cathy Schlund-Vials (cathy.schlund-vials@uconn.edu<mailto:cathy.schlund-vials@uconn.edu>).

Penn Libraries’ Children’s Book Symposium

The Penn Libraries’ Children’s Book Symposium Creating Children’s Books: Collaboration and Change will take place in conjunction with two fall exhibitions in the University of Pennsylvania Libraries. The exhibitions are “As the Ink Flows: Works from the Pen of William Steig” which will explore the life and career of the artist, cartoonist, and children’s book author/illustrator William Steig, and “The School of Atha: Collaboration in the Making of Children’s Books” which celebrates the life and work of Atha Tehon, children’s book designer and longstanding Art Director for Dial Books for Young Readers. The symposium will be held on October 17-18, 2014. For more information and the registration form, go to www.library.upenn.edu/exhibits/childrensbooks_symposium.html.