by Claudia Mills

I came to Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center on a mission, as an avenging angel, if you will. My self-imposed charge: to defend an author I loved as a child, and continue to love, from criticism of her work that I felt was mistaken, or at least misguided.

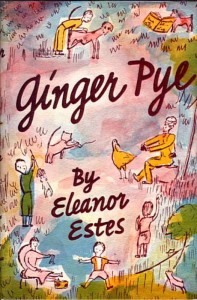

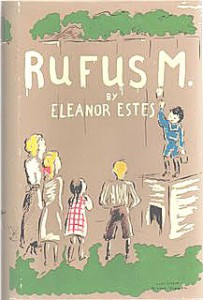

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot.

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot.

The two books about the Pyes (Ginger Pye and Pinky Pye) differ notably from the three earlier books about the Moffats in shifting from an episodic format to a plot structure built around a single, unifying dramatic question, in both cases involving the solving of a mystery. Who stole the Pyes’ dog Ginger Pye? What happened to the little owl lost at sea that ends up becoming Owlie Pye? In both books, the solution to the mystery is extremely obvious, with insistent foreshadowing of the ultimate resolution and blatant, repetitive telegraphing of every clue. This has been widely regarded by adult critics as unsatisfying.

Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

But as I read these two books, Estes isn’t trying and failing to provide a suspenseful mystery. Instead, both books can be read as positively cautioning readers against traditional storytelling techniques, with their “dramatic build-up” and “logical progression toward climax.” Read carefully, both books suggest that suspenseful storytelling can be actually dangerous, its risks greater than its rewards. Estes shows her characters themselves engaging in sensationalist, overly dramatic storytelling with near-disastrous results: for the missing owl (in Pinky Pye) and missing dog (in Ginger Pye. As Papa insists upon theatrical revelation of the discovered location of the little owl, he prolongs the telling of the story to such an extent that the owl is meanwhile endangered by the predatory kitten; as Jerry and Rachel Pye fashion a sensationalist account of Ginger’s kidnapping by an “unsavory character,” they misdirect the police and fail to notice the actual, far more humdrum, culprit. Both books, then, contain within themselves material for a critique of exactly the kind of suspenseful fiction Estes is chided for not providing.

I wondered, however, if Estes herself would share my reading of her books. Perhaps the critics were correct, and she tried and failed to provide more satisfying suspense. Or perhaps I was correct, and her philosophy of storytelling pointed her in a very different direction.

So I spent an enchanted week the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center examining Eleanor Estes’s papers – drafts of speeches she gave throughout her career and extensive editorial correspondence from Ginger Pye’s editor, the legendary Margaret McElderry – in search of support for my claims that Estes did not try and fail to provide suspenseful storytelling in her Pye books, but chose not to do so because of her commitment to a different way of engaging with young readers.

So I spent an enchanted week the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center examining Eleanor Estes’s papers – drafts of speeches she gave throughout her career and extensive editorial correspondence from Ginger Pye’s editor, the legendary Margaret McElderry – in search of support for my claims that Estes did not try and fail to provide suspenseful storytelling in her Pye books, but chose not to do so because of her commitment to a different way of engaging with young readers.

And find it I did.

The collection contains, for the most part, only letters sent to Estes from her editors, rather than letters by Estes herself, so scholars have to read between their lines to recover what Estes must have written to provoke these replies. I learned that Estes apparently considered not resolving the mystery of Ginger Pye’s disappearance at all! McElderry writes to her, as the work is in progress, “Not having read any of it, it is a little difficult to say anything about the problem of who stole him, but I am inclined to agree with you that children reading the book would probably want to know who the culprit is.” McElderry also writes to reassure Estes that certain scenes are not too frightening for children: “I can well imagine the qualms that any author feels at this point but I am perfectly sure you should have none of them. The tramp chapter isn’t the least bit too scary, for look what our modern children have become used to from the radio, television, and the movies. And I expect children will always try to climb rocky cliffs whether they read about it first or not, so that you will not be held responsible for any bruises or cuts.” Indeed, Estes’s lack of interest in traditional plot was so great that in a speech to the Onondaga Library System, she admitted, “Sometimes I write a whole book first, like The Moffats, and then put the plot in.”

The clearest answers to my questions about Estes’s literary method came in Box 16, Folder 201, which contained a sheaf of 4 x 6 index cards with handwritten answers to interview questions for a talk at Albertus Magnus College in 1973. In response to the query “Do you think that violence in children’s literature can psychologically damage a ‘normal’ child?” she first problematizes the whole idea of a “normal child,” noting that children have a wide range of sensitivities; she then confesses that she was one of the more sensitive, who tended “to shy away from extreme violence in life, and on the screen and stage. Even not look when the bad man came on.” She goes on to say, “I am not an escapist. But in books for children . . . I don’t see the necessity of depicting life as it really is.” For Estes, then, it was permissible, even commendable, to prioritize comfort over  danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.

danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.

Of course, along the way I found much, much more. What a window into a now-vanished world of publishing is provided by the yellow Western Union telegram from Margaret McElderry with its all-caps shout of joy: CHEERS FOR GINGER. SEND EXPRESS IN BOX. INTEREST AT BOILING POINT. LOVE MARGARET.

Struggling writers may be cheered to know that Estes, now working for the New York Public Library, showed the manuscript of The Moffats to her supervisor, the formidable Miss Anne Carroll Moore before whose pronouncements authors and editors trembled, only to receive this sole comment: “Well, Mrs. Estes, now that you have gotten this book out of your system, go back to being a good children’s librarian”! (Estes reports that Miss Moore had earlier found it difficult to forgive her for marrying fellow librarian Rice Estes: “she did not like her children’s librarians to get married.”) Once Ginger Pye received the Newbery Medal, however, a friend of Estes’s wrote to her of Miss Moore’s quite different public account of their relationship: now Estes had “risen to the top in the esteem of Annie Carolly Moorey. This great friend through all your struggling years, this inexhaustible dealer-outer of encouragement, has finally had her judgment vindicated. I nearly vomited.”

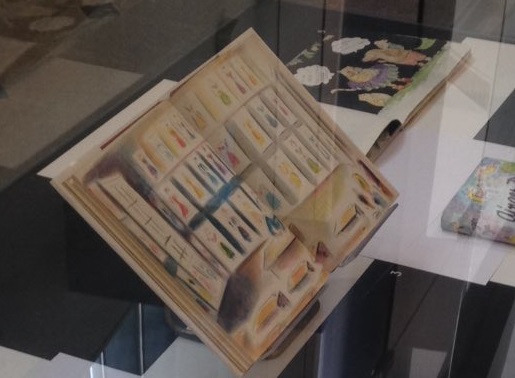

And then there were the pages of scribbled notes with their wonderful revelation of how Estes gathered her ideas in wandering, random bursts of creativity:

Once when I was a dog

A Lion I knew

The story of the pants

These are not the notes of someone who prioritizes the construction of tightly ordered plots, but someone who celebrates the shifting, fragmented way that children look upon and inhabit the fleeting world of childhood.

Claudia Mills is Associate Professor emerita in the Philosophy Department at the University of Colorado at Boulder and a frequent visiting professor at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana. Most of her essays on children’s literature explore ethical and philosophical themes in children’s books. She is also the author of over fifty books of her own for young readers, including most recently The Trouble with Ants (Knopf, 2015, launch title of the Nora Notebooks series about a girl who wants to grow up to be a myrmecologist) and Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee champ (Farrar, 2015, the fourth book in the Franklin School Friends series). Claudia Mills is a 2015 recipient of the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant.

Notes:

[1] Townsend, John Rowe. “Eleanor Estes.” In A Sense of Story: Essays on Contemporary Writers for Children. Philadelphia and New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1971: 79-85.

[2] Wolf, Virginia L., “Eleanor Estes,” in American Writers for Children, 1900-1960, ed. John Cech, Detroit: Gale, 1983: 146-56.

The following is an excerpt of an exhibition essay by Nicolas Ochart, Student Exhibitions Intern in Archives and Special Collections, for an exhibition currently on view in the McDonald Reading Room in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. This semester, Nicolas is responsible for conceiving and developing small-scale exhibitions that highlight archival material found in the collections. He hopes to pursue professional curatorial work in an effort to promote the work and experiences of marginalized and underrepresented communities in the United States. In December, Nicolas will receive his B.A. in Art History from the University of Connecticut.

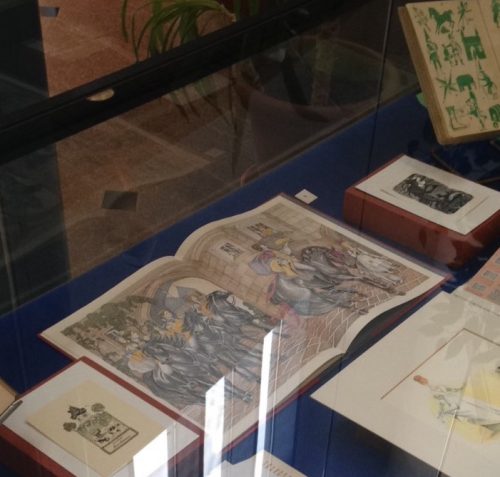

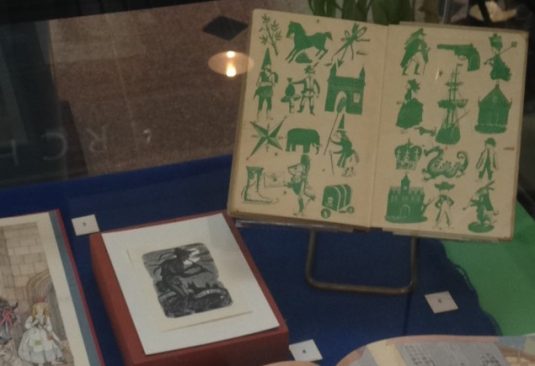

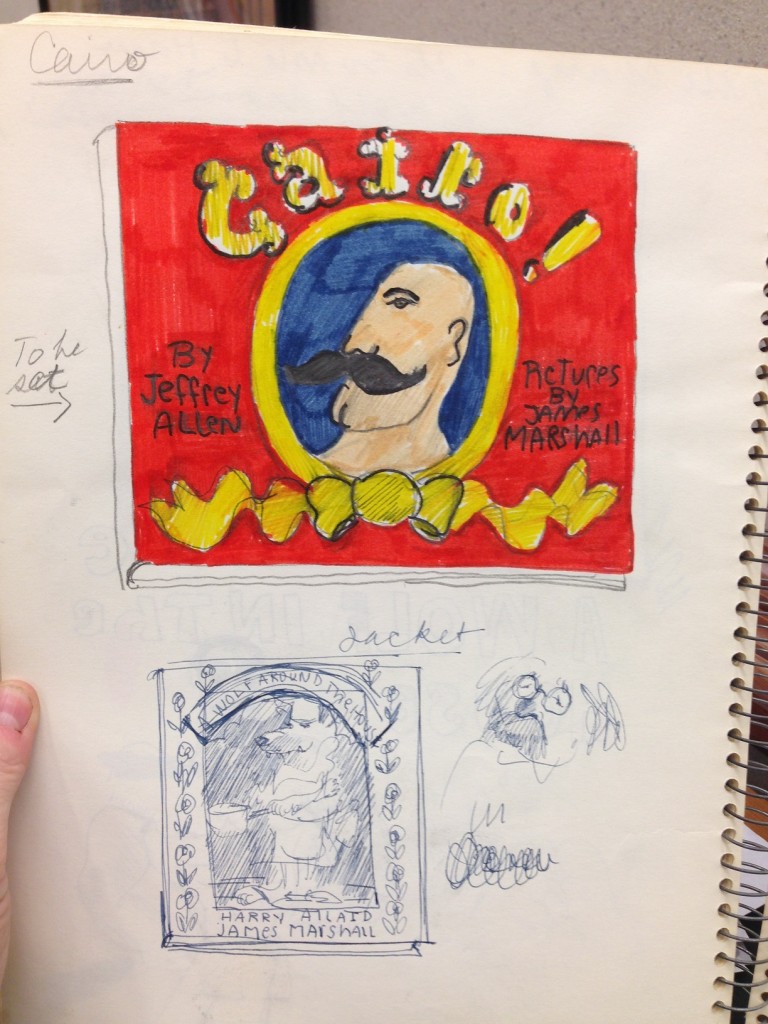

The following is an excerpt of an exhibition essay by Nicolas Ochart, Student Exhibitions Intern in Archives and Special Collections, for an exhibition currently on view in the McDonald Reading Room in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. This semester, Nicolas is responsible for conceiving and developing small-scale exhibitions that highlight archival material found in the collections. He hopes to pursue professional curatorial work in an effort to promote the work and experiences of marginalized and underrepresented communities in the United States. In December, Nicolas will receive his B.A. in Art History from the University of Connecticut. The collection’s extensive holdings have made the University of Connecticut a nexus for scholars and children’s book writers and illustrators across the nation interested in studying the literary and aesthetic qualities of the form. In an effort to support and encourage study of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, Archives and Special Collections have developed a number of awards for researchers, including the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant and the James Marshall Fellowship. Grantees and Fellows have written on such varied topics as queer American Jewishness in the art and writings of Maurice Sendak, as well as influences of modernism and fashion design in the work of Esphyr Slobodkina. Aspiring and established authors and illustrators have also looked at papers by James Marshall, Natalie Babbitt, Tomie dePaola, and Eleanor Estes for guidance in their own practice.

The collection’s extensive holdings have made the University of Connecticut a nexus for scholars and children’s book writers and illustrators across the nation interested in studying the literary and aesthetic qualities of the form. In an effort to support and encourage study of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, Archives and Special Collections have developed a number of awards for researchers, including the Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant and the James Marshall Fellowship. Grantees and Fellows have written on such varied topics as queer American Jewishness in the art and writings of Maurice Sendak, as well as influences of modernism and fashion design in the work of Esphyr Slobodkina. Aspiring and established authors and illustrators have also looked at papers by James Marshall, Natalie Babbitt, Tomie dePaola, and Eleanor Estes for guidance in their own practice.

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot.

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot. Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.

danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.