by JoAnn Conrad

Part of my ongoing research into children’s picturebooks of the mid-twentieth century has to do with the ways in which the work of illustrators has insinuated itself into the public memory even as the names of individual artists may be relatively obscure. This is the case with the rare female artist and, particularly, Esphyr Slobodkina, as her influence is inversely proportional to the obscurity of her name. “Esphyr Slobodkina . . .helped pave the way for the acceptance of abstract art in the United States and translate[d] European modernism into an American idiom.”[1]

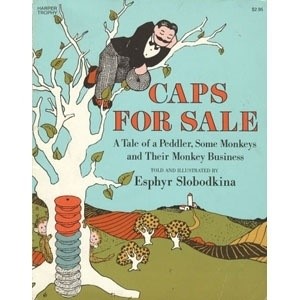

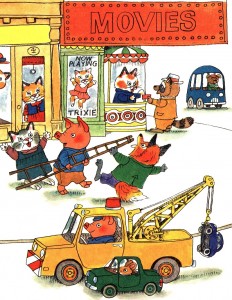

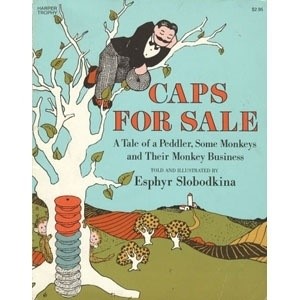

A simple and serendipitous anecdote demonstrates this: While researching her papers at UConn’s Archives and Special Collections this summer, I was living across the street from the UConn Bookstore. One day, I noticed a display in the window announcing “Caps for Sale” [Fig. 1], clearly alluding to one of Slobodkina’s most popular books of the same name [Fig. 2]. The power of the sale poster derives from and depends on the reference to the book, which is assumed to be automatic.

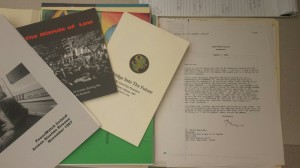

There is a fair amount about Slobodkina’s life and work available. The Finding Aid for the Slobodkina Papers at Archives and Special Collections provides a brief biography as does the website of the Esphyr Slobodkina Foundation. The 2009 Rediscovering Slobodkina: A Pioneer of American Abstraction includes information on her life as well as her contributions to the art world, but the full biography has yet to be written. Esphyr Slobodkina anticipated that it would be written, however, and drafted a comprehensive, detailed, 5-volume manuscript “Notes for a Biographer” which resides in her papers. The Slobodkina Papers contain much more than is in her books – things that would never be published but which give a researcher like me access to insights into the thoughts and motivations of the artist. One of the pleasures of this kind of archival research is not only this intimate and personal connection one makes across time, but also the unexpected revelations into the personality of the artist that informs her work. My intention here is to provide some of those “off the books” glimpses into the work and person – Esphyr Slobodkina.

Esphyr Slobodkina was born to a wealthy Russian-Jewish family in Russia before the Revolution. After the Revolution and her  family’s

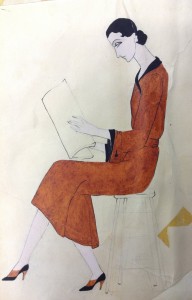

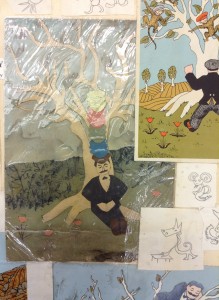

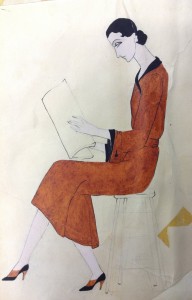

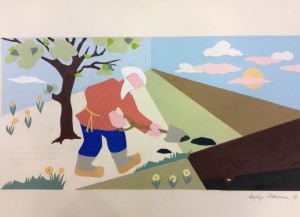

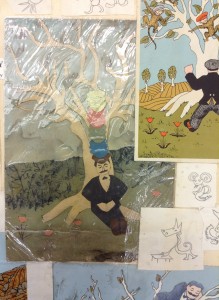

family’s  change in fortune and status, they moved east, to Harbin, and then, via Vladivostok, to the United States. The readjustment to their diminished financial situation was the beginning of her fashion design career – helping her mother sew dresses for clients in Harbin. Throughout her life, Esphyr (whose friends called her Phyra) would sew and consult on fashion and home décor to supplement her income, just as she did with children’s books (in amongst her papers in Box 13 are two experimental fabric children’s books; an attempt at combining her two skills). Slobodkina kept scrapbooks, using large binders of wallpaper samples as her medium. Here, along with dummies for greeting cards, sketches, reviews, letters from children thanking her for her books, fashion design [Fig. 3], the peddler from Caps for Sale interacts with Slobodkina’s “poodies” from her very first children’s book attempt – Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 4]. In these scrapbooks, then, Slobodkina’s various artistic and commercial endeavors combine and interact. Unlike her biographers, perhaps, she did not segregate her work into compartments.

change in fortune and status, they moved east, to Harbin, and then, via Vladivostok, to the United States. The readjustment to their diminished financial situation was the beginning of her fashion design career – helping her mother sew dresses for clients in Harbin. Throughout her life, Esphyr (whose friends called her Phyra) would sew and consult on fashion and home décor to supplement her income, just as she did with children’s books (in amongst her papers in Box 13 are two experimental fabric children’s books; an attempt at combining her two skills). Slobodkina kept scrapbooks, using large binders of wallpaper samples as her medium. Here, along with dummies for greeting cards, sketches, reviews, letters from children thanking her for her books, fashion design [Fig. 3], the peddler from Caps for Sale interacts with Slobodkina’s “poodies” from her very first children’s book attempt – Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 4]. In these scrapbooks, then, Slobodkina’s various artistic and commercial endeavors combine and interact. Unlike her biographers, perhaps, she did not segregate her work into compartments.

After arriving in the US in 1929, Esphyr became one of the founding members of the American Abstract Artists Association, and worked on various WPA projects during the Depression (including many murals in the New York City area). But in 1937, as the Artists’ Union was disintegrating and the New Deal was succeeding, those WPA jobs became more scarce. Phyra again turned to the industrial arts – as a fabric print designer at the Arrow Printing Co. in Patterson, NJ, under the name Phyra Nay.

While still in Russia during those turbulent days, Phyra was not only tutored in art, but was also exposed to the work of the avant-garde that so dominated the art scene of the 1910s and 1920s in Russia: “I liked the early Russians, the Constructivists. And there were some very good women artists – Nathalia [sic] Goncharova. And there were of course decorative Russian artists. I happen not to sneeze at the decorative artists either.” And from another passage about living in Harbin:

We didn’t hear everything but some things reached us . . . There was a great big exhibit of Cubist art in Ufa . . . the next town from the town where I was born [Chelyabinsk]. That was the Cubists of the Italian type, Futurism, and it was all in those primary colors, broken up colors, purple and green . . . and all the nudes were triangles and squares and all broken up like spectral colors. That was as far as we got and we went and we stared and of course we understood nothing, but everyone laughed and said that was modern art [Interview transcript March 23, 1991, in Box 4, Esphyr Slobodkina Papers].

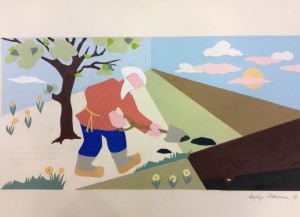

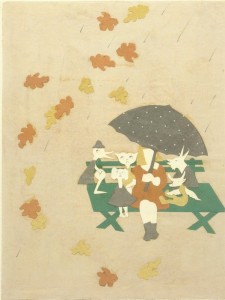

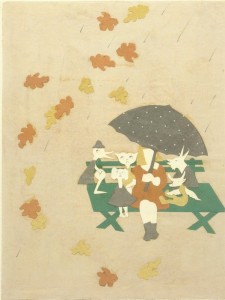

Later, living in the US in the 1930s she describes other influences: “We were into the German Expressionists, with a dash of [Oskar] Kokoschka and [Chaim] Soutin[e] here and there”(Box 1, Esphyr Slobodkina Papers, MSS pg. 517). [2] The avant-garde was to be a major influence in her artistic career as she deepened her interest in abstract art and that most deconstructive of techniques – collage. Here again, Slobodkina was able to translate the techniques of the avant-garde into the “decorative” or public arts, and in the process normalizing an avant-garde aesthetic in the popular imagination. In her collaboration with the great children’s book author Margaret Wise Brown, first with The Little Fireman (1938), then with The Little Farmer (1948) and The Little Cowboy (1948), Slobodkina introduced collage into children’s picturebooks. Barbara Bader would later refer to this pioneering picturebook as “perhaps the apogee of modernism in the picture book.”[3] Slobodkina’s published children’s picturebooks featuring collage are readily available, but in the collection in Archives and Special Collections there are four large collages for an unpublished story “The Turnip that Grew” which she refers to as a “Russian Folktale” (the manuscript for the story is in Box 2, the pictures are framed but are also part of the collection) [Fig. 5].

Later, living in the US in the 1930s she describes other influences: “We were into the German Expressionists, with a dash of [Oskar] Kokoschka and [Chaim] Soutin[e] here and there”(Box 1, Esphyr Slobodkina Papers, MSS pg. 517). [2] The avant-garde was to be a major influence in her artistic career as she deepened her interest in abstract art and that most deconstructive of techniques – collage. Here again, Slobodkina was able to translate the techniques of the avant-garde into the “decorative” or public arts, and in the process normalizing an avant-garde aesthetic in the popular imagination. In her collaboration with the great children’s book author Margaret Wise Brown, first with The Little Fireman (1938), then with The Little Farmer (1948) and The Little Cowboy (1948), Slobodkina introduced collage into children’s picturebooks. Barbara Bader would later refer to this pioneering picturebook as “perhaps the apogee of modernism in the picture book.”[3] Slobodkina’s published children’s picturebooks featuring collage are readily available, but in the collection in Archives and Special Collections there are four large collages for an unpublished story “The Turnip that Grew” which she refers to as a “Russian Folktale” (the manuscript for the story is in Box 2, the pictures are framed but are also part of the collection) [Fig. 5].

Collage was also the basis for the illustrations of Caps for Sale and the one of the original collages is  pasted in the aforementioned scrapbook [Fig. 6]. Preserved under plastic wrap, the image not only makes emphatic the link between handiwork and art, but also is penetrated by the impish Poodies. Slobodkina, in an interview, relates that the inspiration for the book came from a story she heard being told by the teacher of her sister-in-law’s child, and because of this ambiguous authorship, that William Scott had been hesitant to publish it. On the advice of Bertha Mahoney (of The Horn Book), Esphyr gave the peddler a name, and developed the plot more, whereby it was published by Harper Collins (1940) under the editorship of Ursula Nordstrom, and then later by Scott.

pasted in the aforementioned scrapbook [Fig. 6]. Preserved under plastic wrap, the image not only makes emphatic the link between handiwork and art, but also is penetrated by the impish Poodies. Slobodkina, in an interview, relates that the inspiration for the book came from a story she heard being told by the teacher of her sister-in-law’s child, and because of this ambiguous authorship, that William Scott had been hesitant to publish it. On the advice of Bertha Mahoney (of The Horn Book), Esphyr gave the peddler a name, and developed the plot more, whereby it was published by Harper Collins (1940) under the editorship of Ursula Nordstrom, and then later by Scott.

I want to close this insider’s look into the Slobodkina papers with the one item that is not  only my favorite, but which shows how funny, creative, and engaging Phyra was. It again is related to Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 7], an unpublished children’s book that served as Esphyr’s introduction to Margaret Wise Brown and Wm. Scott Publishers. The book was not an ideological fit with the Bank Street “Here-and-Now” pedagogues because it featured the whimsical imaginary creatures – the eponymous Poodies.[4] But the art work and use of collage attracted their attention and eventuated in the collaborative work between MWB and Slobodkina that began with The Little Fireman. In the Slobodkina Papers, however, was a small “promotional” sheet that she’d worked up for Mary and the Poodies, a kind of contest for kids to name the Poodies. To the first to respond awaits either a Bachelors or a Masters of Poodology, conferred by Prof. Amoritus Maximus!

only my favorite, but which shows how funny, creative, and engaging Phyra was. It again is related to Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 7], an unpublished children’s book that served as Esphyr’s introduction to Margaret Wise Brown and Wm. Scott Publishers. The book was not an ideological fit with the Bank Street “Here-and-Now” pedagogues because it featured the whimsical imaginary creatures – the eponymous Poodies.[4] But the art work and use of collage attracted their attention and eventuated in the collaborative work between MWB and Slobodkina that began with The Little Fireman. In the Slobodkina Papers, however, was a small “promotional” sheet that she’d worked up for Mary and the Poodies, a kind of contest for kids to name the Poodies. To the first to respond awaits either a Bachelors or a Masters of Poodology, conferred by Prof. Amoritus Maximus!

JoAnn Conrad is a professor of Anthropology and Folklore at California State University, East Bay (Hayward). Her current research focuses on the impact of immigrant artists on the American cultural landscape in the post-WWII period, particularly in their role as illustrators of children’s picture books. Conrad feels that these immigrant artists, through their work in such quotidian, mass-produced materials as children’s books, magazines, and even film and animation, were important translators of a modernist aesthetic into the day-to-day lives and sensibilities of millions for whom the art world was a distant and foreign sphere. Conrad has researched such artists as Feodor Rojankovsky, Tibor Gergely, and Gustaf Tenggren. In Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, she was specifically researching Esphyr Slobodkina and Leonard Weisgard (not an immigrant to the US, but influenced by European modernism). Conrad is the recipient of the 2015 Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant.

Sources cited:

All archival material referenced is from the Esphyr Slobodkina Papers. Archives & Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

[1] Slobodkina, Esphyr, and Sandra Kraskin. Rediscovering Slobodkina: A Pioneer of American Abstraction : [ Catalog of an Exhibition Held at the Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, Ny … between Jan. 10, 2009 and Apr. 18, 2010]. Manchester, Vt: Hudson Hills Press, 2009. Print.

[2] In an email correspondence with John Bowlt, dated Aug. 6, 2015, he indicates that David Burliuk, the so-called “Father of Russian Futurism”, held a one-man show in Ufa in 1916.

[3] Barbara Bader, “A Lien on the World.” (New York Times Book Review, November 9, 1980): 66.

[4] For more on the collaborative work of Margaret Wise Brown and Esphyr Slobodkina, see Leonard Marcus, “Modernist At Story Hour: Esphyr Slobodkina and the Art of the Picture Book” (http://www.slobodkinafoundation.org/books-illustrations/essay-by-leonard-marcus/).

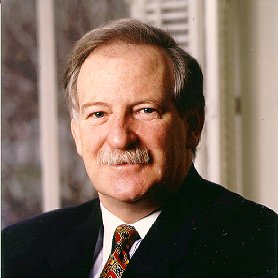

Today November 19 at 4:00pm in UConn’s Konover Auditorium, the Edwin Way Teale Lecture Series on Nature and the Environment presents Dr. Robert Nixon, The Thomas A. and Currie C. Barron Family Professor in Humanities and the Environment at Princeton University.

Today November 19 at 4:00pm in UConn’s Konover Auditorium, the Edwin Way Teale Lecture Series on Nature and the Environment presents Dr. Robert Nixon, The Thomas A. and Currie C. Barron Family Professor in Humanities and the Environment at Princeton University.

family’s

family’s  change in fortune and status, they moved east, to Harbin, and then, via Vladivostok, to the United States. The readjustment to their diminished financial situation was the beginning of her fashion design career – helping her mother sew dresses for clients in Harbin. Throughout her life, Esphyr (whose friends called her Phyra) would sew and consult on fashion and home décor to supplement her income, just as she did with children’s books (in amongst her papers in Box 13 are two experimental fabric children’s books; an attempt at combining her two skills). Slobodkina kept scrapbooks, using large binders of wallpaper samples as her medium. Here, along with dummies for greeting cards, sketches, reviews, letters from children thanking her for her books, fashion design [Fig. 3], the peddler from Caps for Sale interacts with Slobodkina’s “poodies” from her very first children’s book attempt – Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 4]. In these scrapbooks, then, Slobodkina’s various artistic and commercial endeavors combine and interact. Unlike her biographers, perhaps, she did not segregate her work into compartments.

change in fortune and status, they moved east, to Harbin, and then, via Vladivostok, to the United States. The readjustment to their diminished financial situation was the beginning of her fashion design career – helping her mother sew dresses for clients in Harbin. Throughout her life, Esphyr (whose friends called her Phyra) would sew and consult on fashion and home décor to supplement her income, just as she did with children’s books (in amongst her papers in Box 13 are two experimental fabric children’s books; an attempt at combining her two skills). Slobodkina kept scrapbooks, using large binders of wallpaper samples as her medium. Here, along with dummies for greeting cards, sketches, reviews, letters from children thanking her for her books, fashion design [Fig. 3], the peddler from Caps for Sale interacts with Slobodkina’s “poodies” from her very first children’s book attempt – Mary and the Poodies [Fig. 4]. In these scrapbooks, then, Slobodkina’s various artistic and commercial endeavors combine and interact. Unlike her biographers, perhaps, she did not segregate her work into compartments.

pasted in the aforementioned scrapbook [Fig. 6]. Preserved under plastic wrap, the image not only makes emphatic the link between handiwork and art, but also is penetrated by the impish Poodies. Slobodkina, in an interview, relates that the inspiration for the book came from a story she heard being told by the teacher of her sister-in-law’s child, and because of this ambiguous authorship, that William Scott had been hesitant to publish it. On the advice of Bertha Mahoney (of The Horn Book), Esphyr gave the peddler a name, and developed the plot more, whereby it was published by Harper Collins (1940) under the editorship of Ursula Nordstrom, and then later by Scott.

pasted in the aforementioned scrapbook [Fig. 6]. Preserved under plastic wrap, the image not only makes emphatic the link between handiwork and art, but also is penetrated by the impish Poodies. Slobodkina, in an interview, relates that the inspiration for the book came from a story she heard being told by the teacher of her sister-in-law’s child, and because of this ambiguous authorship, that William Scott had been hesitant to publish it. On the advice of Bertha Mahoney (of The Horn Book), Esphyr gave the peddler a name, and developed the plot more, whereby it was published by Harper Collins (1940) under the editorship of Ursula Nordstrom, and then later by Scott.

For my final blog post of my summer internship, I want to touch on something that’s been nagging at me ever since I began my work.

For my final blog post of my summer internship, I want to touch on something that’s been nagging at me ever since I began my work.

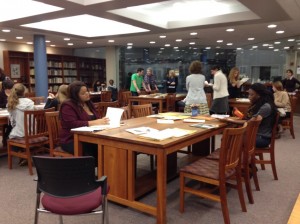

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources.

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources.