Anna Zarra Aldrich is majoring in English, political science and journalism at the University of Connecticut. She is a student writing intern studying historical feminist publications from the collections of Archives and Special Collections. The following guest post is one of a series to be published throughout the Spring 2018 semester.

The second advent of the feminist movement that washed over American society in the 1960s and 1970s like a tidal wave emphasized a pervasive message of empowerment which manifested in a variety of periodicals during this period, including art journals.

Women had largely been excluded from the world of fine art for centuries as geniuses like Michelangelo, Van Gogh, Picasso, Dali and Monet were celebrated and revered while their female contemporaries, such as Georgia O’Keefe or Frida Kahlo, were few and far between as their talent went largely unencouraged and unrewarded.

Women had largely been excluded from the world of fine art for centuries as geniuses like Michelangelo, Van Gogh, Picasso, Dali and Monet were celebrated and revered while their female contemporaries, such as Georgia O’Keefe or Frida Kahlo, were few and far between as their talent went largely unencouraged and unrewarded.

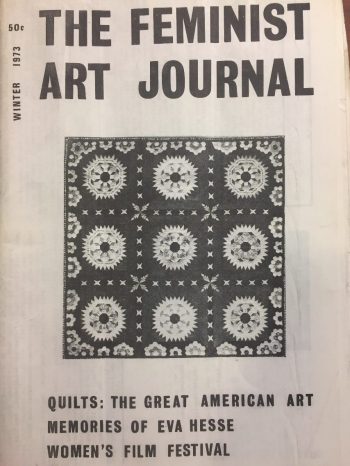

“The Feminist Art Journal” was published quarterly from 1972 to 1977 out of Brooklyn, New York by Feminist Art Journal Inc. One of the early editions of the journal from 1973 addresses the idea that women have created art for the centuries during which they were strictly confined to the home. An article titled: “Quilts: The Great American Art,” discusses how quilts, tapestries and other home décor have acted as mediums of female artistic expression that have historically been disregarded by men as mere frivolous decorations. The article states that, “Women have always made art. But for most women, the arts highest valued by male society have been closed to them for just that reason.”

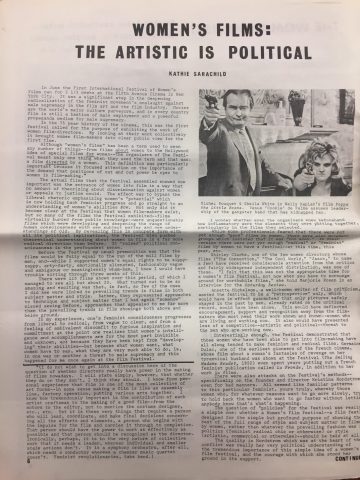

An editorial from the same issue emphasizes the need of women to “rediscover their own history.” One of the primary aims of “The Feminist Art Journal” was to reclaim women’s place in art history through articles such as the one on quilts and by discussing issues of female representation in classical art. An intriguing article on Marie De Medici from the Summer 1977 issue explores how the powerful Florentine heir-turned-French-monarch commissioned portraits of herself and her life accomplishments like those that were traditionally done for prominent males of the period. Medici also pointedly decorated her palace with statues of great women like Saint Bathilde and George Sand. The article emphasizes how Marie de Medici understood the power of art as a political statement,  underscoring another one of the journal’s core messages: art is political.

underscoring another one of the journal’s core messages: art is political.

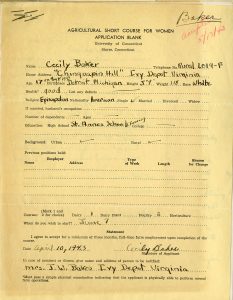

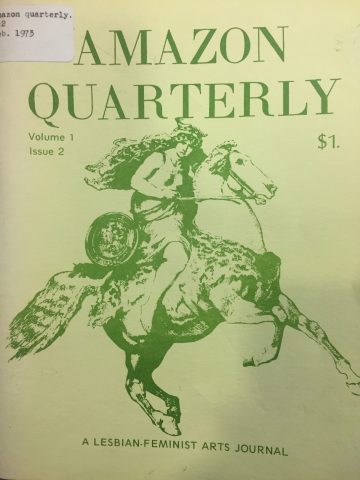

Interestingly, a short-lived lesbian feminist journal published from 1973 to 1975, the “Amazon Quarterly: A Lesbian-Feminist Art Journal” expressed a much different viewpoint from “The Feminist Art Journal”. “Amazon Quarterly” was published from the other side of the country, in Oakland, California by Amazon Press. It should be noted that both of these journals were published independently, sustained by revenue from subscriptions, single issue sales and advertisements. Both journals also had exclusively female editors.

The “Amazon Quarterly” commended women’s lack of participation in the male-dominated art world, in which they were routinely objectified in the works of male artists, rather than seeking to place women’s accomplishments within this patriarchal frame work.

Both “The Feminist Art Journal” and “Amazon Quarterly” promoted and provided a platform for female artists to share their literature, poetry, drawings, photography. However, “Amazon Quarterly” made promoting the art of women, specifically lesbians, its primary artistic goal, rather than engaging in discussions of history.

The division in purpose and ideology of these two journals which served, broadly, the same role, reflected a deeper division in the feminist movement between lesbians and straight women. Some lesbians believed women could not fully participate in the true revolution of the feminist movement so long as they were still sexually involved with their male oppressors, a radical idea that is discussed in articles published in the journal.

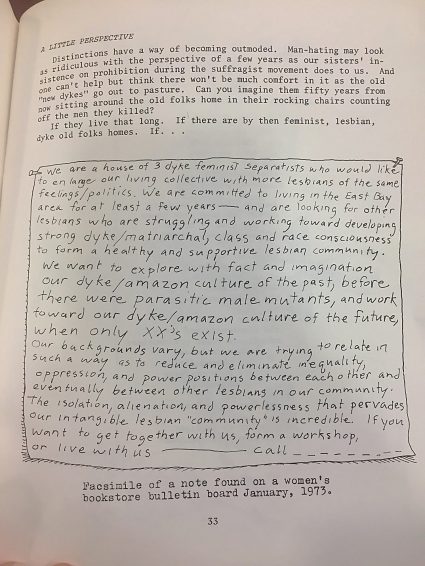

In an article, “Distinctions: The Circle Game” from the February 1973 issue of

“Amazon Quarterly” written by one of the editors, Laurel Galana, whose byline is simply a familiar: Laurel, explores these divisions within the movement.

Laurel breaks down the group of women who are feminists into increasingly small subcultures from lesbians to “new lesbians” to dykes. The “new lesbians” Laurel describes had several verboten relations including those with men and straight women, whom they viewed as “men’s women.”

Laurel breaks down the group of women who are feminists into increasingly small subcultures from lesbians to “new lesbians” to dykes. The “new lesbians” Laurel describes had several verboten relations including those with men and straight women, whom they viewed as “men’s women.”

Laurel herself abides by these taboos, she explains, “My energy, my time, my sisterly love was indirectly useful to the male for keeping his woman content. And secondly, I decided not to relate to straight women because they already had made a choice which did not include me – that is all of me.”

The piece goes on to criticize lesbians who distinguish themselves based on class, believing that such internal divisions will only cause the movement to fracture and be less effective. She seems to miss the irony of the fact that she believes lesbians should not associate with straight feminists and form a united front of all feminist women.

Much of the art and especially the literature published in the journal reflected the fact that “Amazon Quarterly” branded itself as a periodical that intended to cater specifically to lesbian women. Many of the pieces published in the journal deal with tales and the feelings associated with homosexual awakenings and attraction. The publication had an entire issue dedicated to the topic of sexuality as their swan song before shutting down in 1977.

While the journal ceased publication in 1977, the editors went on to run Bluestocking Books, a publishing house which published a few novels including “The Violent Sex” by Laurel Holliday. Holliday’s book confronted the evolution of masculine sexuality and behavior that has led to the sexual and social oppression of women.

Despite their differences, both these journals considered art in an expansive sense, including all forms of visual and literary art, and stressed the importance of the inclusion of the female perspective in them.

Despite their differences, both these journals considered art in an expansive sense, including all forms of visual and literary art, and stressed the importance of the inclusion of the female perspective in them.

While these two journals had different audiences and somewhat different goals, they both served to underscore the important idea that art is political, and that women had to understand how they could use any and all forms of art to express their ideas and achieve their objectives.

The art of many female artists of the period, during which feminist art truly began to flourish and find its foothold, was clearly in line with this philosophy. Some notable works include Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party,” which portrays a dinner party of 39 notable historical women, and Hannah Wilke’s avant garde “Starification Object Series,” a series of photographs for which she covered her body with wads of gum folded to resemble female genitalia.

These two journals and the art they supported show how women utilized the arts to promote the feminist agenda as they worked toward achieving social and political equality despite divisions within the movement.

In a 1977 interview published in “Chrysalis” magazine, Chicago commented on the value of art to the feminist movement.

“Art is particularly important for women and can catapult women into a different realm of consciousness by symbolizing and objectifying our experience. That expression, that impulse, has such potential power, and it is that power that society tries to contain by trivializing, by repressing, by suppressing the art impulse,” Chicago said. “As long as women participate in that process, we will never be able to realize our full creative potential. We must bust out of that, just absolutely bust out of that and reclaim art as the basic outpouring of the human spirit and pour out our songs and all our feelings and all our beliefs and all our visions in a way that everyone can hear.”

-Anna Zarra Aldrich