The Archives & Special Collections reading room is closed on Monday, September 5, for the Labor Day holiday.

Black Experience in the Arts: Playwright Leslie Lee

-Guest blog post by Marc Reyes, doctoral student at the University of Connecticut and 2016 Summer Graduate Intern in Archives and Special Collections.

“Now, I am a black playwright; I am not a playwright who happens to be black…I am very happy writing about black people. I do not have to write about anybody else.”

“Now, I am a black playwright; I am not a playwright who happens to be black…I am very happy writing about black people. I do not have to write about anybody else.”

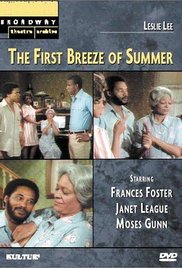

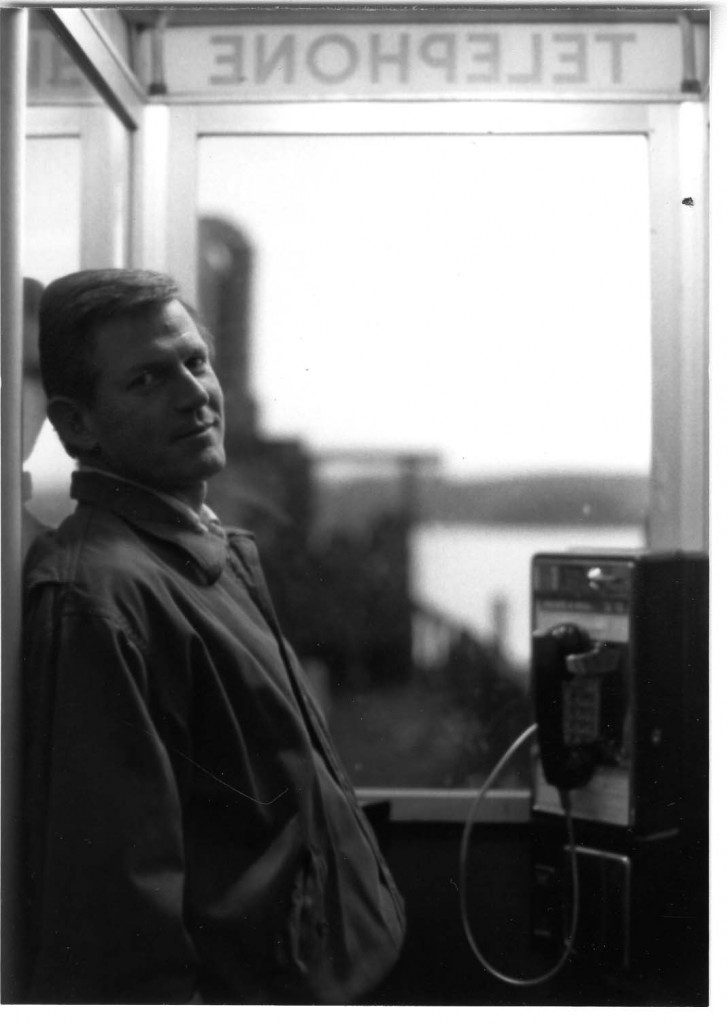

Those words were spoken by dramatist Leslie Lee, a renowned writer of stage and screen. When Lee was not scripting Tony Award-nominated plays or acclaimed television programs, he spoke to students about his life, writing career, and creative process. Lee visited the University of Connecticut on September 29, 1987 as a guest speaker for the university’s course, Black Experience in the Arts. The class, offered through the School of Fine Arts, debuted in the Fall semester of 1970 and lasted under this name until the mid-1990s. During the course’s lifetime, UConn undergraduates heard from hundreds of black artists, representing fields such as music, dance, poetry, sculpture, and architecture. Many of the invited presenters were performers with a myriad of memories and achievements as well as thoughts about what it meant to be a black artist in America. Course notes, typed lecture transcriptions, and over three hundred audio recordings are some of the materials found in Archives and Special Collections’ Black Experience in the Arts collection. This collection offers researchers an exciting look into a course dedicated to highlighting the contributions of black artists and the power of art as a mechanism for social change and racial expression. From this vantage point, scholars of the American experience gain a richer understanding of the black arts movement of the 1960s and 1970s and how black artistic expression was a crucial element of the civil rights and later black power movements.

When Lee spoke in the Fall of 1987, he was one of the few playwrights that addressed the class. Most of the speakers who represented black theater were actors or directors, but Lee offered insights into how a writer expresses their creative vision through different mediums. Of all the ways his writing was expressed – through films, television, and novels – his first love was theatre because it was the most verbal. He explained, “But in the theater it is my play and it is my vision, and those persons who are directing, or the set designers, or the costume designers, the lighting designers, the actors are an extension of me…”

Besides discussing his career, Lee told students about his middle-class upbringing in Pennsylvania and how family members, like his grandmother, were inspirations for some of his play’s most memorable characters. He also explained how his interest in writing and the arts was not predestined, in fact, Lee confided to his audience that his artistic journey started later in life. Growing up he wanted to be a doctor and even spent years as a cancer researcher, but his passion for writing overwhelmed all else and he returned to school to study playwriting at Villanova University. After graduating, Lee worked as a writing instructor at several colleges and adapted for television Richard Wright’s Almos’ a Man. But his big break came with the staging of his 1975 play, “The First Breeze of Summer.” The production won three Obie Awards (the top honor for Off-Broadway productions) including Best New American Play and then moved to Broadway where it was later nominated for a Tony Award in the Best Play category.

In his lecture, Lee stressed to the students that to be a successful writer, one must have something important to say. Their voice must communicate a message that can even reach international audiences. With his voice, Lee strove to produce works that celebrated blackness and displayed the beauty of black bodies. He lamented seeing blacks thin their lips, alter their noses, and bleach or peel their skin to appear lighter. He remembered marching in the 1960s to the chants of “Black is Beautiful” and how the collective faith in that message erased the doubts he had about the beauty of black bodies. From that moment, he wanted his work to produce a similar feeling in black Americans. As for the characters found in Lee’s works, his heroes are the everyday black man or woman “who struggle daily against racism and against other things that are constantly impinging upon their consciousness.” Finding theatre to be the best avenue for exploring black consciousness, Lee developed an array of three-dimensional black characters that tackled issues such as systematic racism and the horrors of war.

Beyond individual depictions, Lee was also concerned in the ways black families were depicted in the arts. He believed black families, like the ones found on The Jeffersons and Good Times, were almost always portrayed in comic lights, making it easier to not take black people, and their concerns, seriously. He recounted a story about a reviewer who saw his play “Hannah Davis,” which centered on the actions of an upper-class black family. Although the work received many positive reviews, one critic panned the play. The critic found the piece problematic because he could not envision that a well-to-do black family like this existed. Lee rejected the shallow criticism and informed the reviewer that the family in the play was based on a real black family, but the experience reinforced in Lee the need to project stronger images of black people and their families than the depictions usually found on television or motion pictures.

Beyond individual depictions, Lee was also concerned in the ways black families were depicted in the arts. He believed black families, like the ones found on The Jeffersons and Good Times, were almost always portrayed in comic lights, making it easier to not take black people, and their concerns, seriously. He recounted a story about a reviewer who saw his play “Hannah Davis,” which centered on the actions of an upper-class black family. Although the work received many positive reviews, one critic panned the play. The critic found the piece problematic because he could not envision that a well-to-do black family like this existed. Lee rejected the shallow criticism and informed the reviewer that the family in the play was based on a real black family, but the experience reinforced in Lee the need to project stronger images of black people and their families than the depictions usually found on television or motion pictures.

Leslie Lee’s September 1987 visit to UConn’s Black Experience in the Arts class discussed the personal and artistic fulfillment that can be found in the performing arts and encouraged students to consider a career in drama and make a home in black theatre. For interested students, he referred to the Negro Ensemble Company which produced many of Lee’s plays and has been a training ground for black actors such as Lawrence Fishburne, Angela Bassett, and Denzel Washington. Lee asserted that more black writers and actors were needed to produce multi-dimensional and complex black characters. He also wished black students would pursue theatre criticism because he believed black critics would bring greater insights when evaluating the works of black playwrights.

There are many more exciting ideas and profound lessons found in Lee’s lecture which can be explored in the Black Experience in the Arts collection at Archives and Special Collections. Stay tuned as we continue to make these valuable materials more widely known and available as well as additional blog posts highlighting other prominent lecturers who visited the university and spoke to students about the Black Experience in the Arts.

Marc Reyes is a doctoral student in the Department of History at the University of Connecticut. He received his B.A. in History from the University of Missouri and his M.A., also in History, from the University of Missouri-Kansas City. His research investigates the United States and its interactions – diplomatically, economically, and culturally – with India. As a 2016 graduate intern, Marc is excited to gain additional experience working in a university archive and will be exploring the history of the Black Experience in the Arts course here at UConn as well as the broader movement of 20th century black expression in the arts.

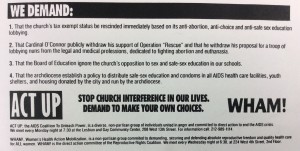

#AIDS35

-Guest blog post by Thomas Lawrence Long, Associate Professor and co-curator of the AIDS35 exhibition on display in the John P. McDonald Reading Room, Archives & Special Collections during the months of August and September, 2016.

In 2016 we mark the thirty-fifth anniversary of the first published reports of what would come to be called the AIDS epidemic. Initially identified as rare cancers among gay men, Haitian immigrants, intravenous drug users, and hemophiliacs, AIDS emerged at a moment when a triumphant religious right (organized by the so-called Moral Majority) and political conservatives dominated American media and public life. The convergence of a mysterious infectious disease associated with stigmatized groups or behaviors, on the one hand, and a moralistic neo-liberal social and political movement, on the other hand, created the conditions for competing published representations. These representations invoked divine judgment and apocalyptic anxiety, or critiques of conservative medical authorities and of defunded public health resources.

HIV, the virus causing AIDS, is often transmitted by proscribed behaviors: sexual intercourse (both vaginal and anal) and intravenous drug use. HIV-infected people were thus routinely blamed for their infection and stigmatized as a threat to the general population. Even among gay men for whom sexual liberation was associated with social and political freedom, the AIDS epidemic created a crisis of confidence.

In a paper presented in 1986 at the annual convention of the Modern Language Association and later published in 1988, communication and cultural theorist Paula Treichler, analyzing the representational conflicts surrounding AIDS, observed that “the AIDS epidemic is simultaneously an epidemic of a transmissible disease and an epidemic of meanings or signification. Both epidemics are equally crucial for us to understand, for, try as we may to treat AIDS as ‘an infectious disease’ and nothing more, meanings continue to multiply wildly and at an extraordinary rate.”

To wrest control of the epidemic’s representational field, AIDS activists, independent queer presses, and AIDS service organizations produced a variety of publications, including safer-sex brochures, tracts and manifestos, zines, and AIDS-themed fiction. Items included in this exhibit come both from Archives and Special Collections and the personal collection of Associate Professor in Residence Thomas Lawrence Long.

To wrest control of the epidemic’s representational field, AIDS activists, independent queer presses, and AIDS service organizations produced a variety of publications, including safer-sex brochures, tracts and manifestos, zines, and AIDS-themed fiction. Items included in this exhibit come both from Archives and Special Collections and the personal collection of Associate Professor in Residence Thomas Lawrence Long.

Ironically, this year marks another AIDS anniversary: twenty years since the introduction of protease inhibitors and other retroviral drug combinations that turned HIV infection from a death sentence to a manageable chronic infection.

For more information on campus wide exhibitions and programming on #AIDS35, click here.

-Thomas Lawrence Long, Associate Professor in residence in the UConn School of Nursing with a joint appointment in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, is the author of AIDS and American Apocalypticism: The Cultural Semiotics of an Epidemic. He is a founding member of the Modern Language Association’s Medical Humanities and Health Studies Forum and an associate editor of Literature and Medicine.

Are Photographs a Truly Reliable Primary Source?

Do you notice something different about these two images?

I’m sure you see it — in the second photograph there is a man standing on top of the box car. These two digital images are from the same actual, physical object of a photographic print. What do you think happened here?

I’m sure you see it — in the second photograph there is a man standing on top of the box car. These two digital images are from the same actual, physical object of a photographic print. What do you think happened here?

It’s an interesting story. This photograph, of the Granby, Connecticut, railroad station, was taken around 1930 by the noted regional photographer Lewis H. Benton, who was born in Taunton, Massachusetts, in 1872 or 1873 and worked for the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad as a clerk. In his free time he would travel around the region with his sidekick Irving Drake and take photographs of railroad stations and structures. In both versions of the photograph you will see Mr. Drake’s sedan near the station; in the second image that’s him on top of the railroad car. This image was donated along with thousands of other photographs of railroad locomotives, stations, and scenes by Mr. Francis D. Donovan of Medford, Massachusetts, in 2006.

Recently we had a visit to the archives of Mr. Robert Belletzkie, a very knowledgeable railroad historian who maintains a website focusing on railroad stations in Connecticut — TylerCityStation.info. Mr. Belletzkie was conducting his research in the Donovan Papers, saw the photograph, the version without Mr. Drake on top of the car, and knew something was wrong. He had seen this same image before in other collections (which is not uncommon; railroad photograph collectors routinely make copies and share the prints among themselves) but he knew the photograph to have the image of Mr. Drake on top of the box car.

Mr. Belletzkie brought the photograph to my attention and we took a close look at it. A small dot of white-out had been placed on the print to cover up the image of Mr. Drake in the photo. How intriguing! Who would have done that, and why? It was certainly done before the collection was donated to Archives & Special Collections. Did Mr. Donovan do it? Did someone do it before that particular print made its way to Mr. Donovan?

Mr. Belletzkie offers this explanation — “Whoever covered up Mr. Drake thought it was inappropriate for him to be seen posturing in a serious station photograph or perhaps even that Mr. Benton was unaware of him up there and did not intend him to be in the shot. A larger study of the Benton & Drake photos currently underway, however, shows several shots with a similar, humorous touch. The eradicator’s sense of propriety may have been offended but anyone who retouches historical photographs does a disservice to future generations by not passing on something exactly as its creator intended.”

Well, who or however it happened, I wanted to set the record straight. Yesterday I gave the print to the UConn Library’s Conservation Librarian, Carole Dyal, who expertly scraped off the white-out to reveal Mr. Drake on top of the railroad car.

We’ve come to expect that photographs reveal the truth of any historical moment. Sometimes we have to remember that photographs can be altered and obscured, which affects our knowledge of historical events.

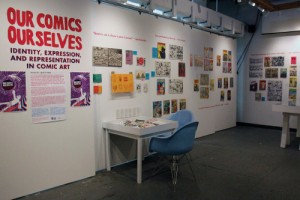

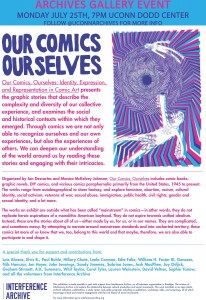

Our Comics, Ourselves Gallery Event

The Archives & Special Collections will be hosting a Gallery Event on Monday, July 25th at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center on the University of Connecticut, Storrs Campus at 7pm. Co-Curator and webcomic creator Jan Descartes will lead the event to discuss DIY comics, art and social justice issues represented in the Our Comics, Ourselves exhibition currently on display in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, on loan from the Interference Archive in Brooklyn, NY until August 22nd, 2016.

The Archives & Special Collections will be hosting a Gallery Event on Monday, July 25th at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center on the University of Connecticut, Storrs Campus at 7pm. Co-Curator and webcomic creator Jan Descartes will lead the event to discuss DIY comics, art and social justice issues represented in the Our Comics, Ourselves exhibition currently on display in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, on loan from the Interference Archive in Brooklyn, NY until August 22nd, 2016.

This event is free and open to public. Parking is available on Whitney Road and behind the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center after 5pm.

For further information, please follow us on Twitter or contact Archivist Graham Stinnett

Convention!

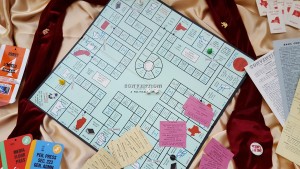

Currently on display in the John P. McDonald Reading Room at the Archives & Special Collections: Convention!: An Exciting and Educational Board Game Created by Homer and Marcia Babbidge

In 1960 Homer D. Babbidge, who would later became UConn’s President (1962-1972),  was an Assistant for Higher Education in the U.S. Office of Education. To whet his appetite for the game of politics, in the midst of the 1960 Presidential campaign, he and his wife, Marcia, invented a board game published by Games Research, in which the players seek to accumulate enough delegates to win the nomination.

was an Assistant for Higher Education in the U.S. Office of Education. To whet his appetite for the game of politics, in the midst of the 1960 Presidential campaign, he and his wife, Marcia, invented a board game published by Games Research, in which the players seek to accumulate enough delegates to win the nomination.

The UConn University Archives has recently acquired two editions of this long-forgotten game for its collection, thanks to Norman D. Stevens, Director of University Libraries Emeritus. When Norman became aware of the game, he contacted David Beffa-Negrini (Class of 1976), a noted jigsaw puzzle maker and an active game collector. Mr. Beffa-Negrini immediately located the two copies of the game currently on display and generously donated them to the Archives.

The probable first edition of the game includes a colorful tube which contains a rolled paper game board sheet and two instruction sheets, game pieces, dice and score sheet. The likely later edition is a typical board game housed in a cardboard box containing the game board, similar in many ways to Monopoly™. Convention!, which reflects the Babbidge’s fondness for satire, is much more volatile than any other board game. As one newspaper reporter who played the game wrote, “It is filled with all sorts of pitfalls and windfalls whereby a player might lose or win delegates. One neighbor lady…had won most of the primaries and was pressing in for the kill. I was down to a few delegates and was about to withdraw. Then I remembered a maneuver that Babbidge had told me about but which I had neglected to mention while explaining the rules. In one stroke I had captured enough delegates from the other players to win the nomination.” It was also reported that John F. Kennedy had a copy of Convention! on his campaign plane but how well he was doing was a secret.

In addition to the spaces around the board, through which delegates may be lost or won, there are seven caucuses, leading from a perimeter space that candidates may enter in hopes of winning more delegates. In the New York caucus a candidate can win votes for landing on the Wall Street Likes You space, or lose them for landing on the Greeted by a Bronx Cheer space. It can be the desperation move mentioned above for, if a player chooses to enter the Smoke Filled Room, on 2 of each six spaces the Bosses Approve, Disapprove, or Ignore you. Approval garners the player half of the Uncommitted Delegates held by each other candidate but Disapproval eliminates the player from the game.

Exhibit contents are from the Papers of Stuart Rothenberg and Herman Wolf and recent donations from Emily Roth (Class of 1965), Bill Heath and Henry Krisch (Professor of Political Science).

Curated by A. Gabrielle Westcott and Betsy Pittman

Reading Room Closed Monday July 4

The Archives and Special Collections Reading Room, and the University, will be closed this Monday, July 4 for the federal holiday. Regular Reading Room hours of 9:00am to 4:00pm resume on Tuesday, July 5.

Bill Berkson, Poet, Teacher, Art Critic, Archivist and Friend: 1939-2016

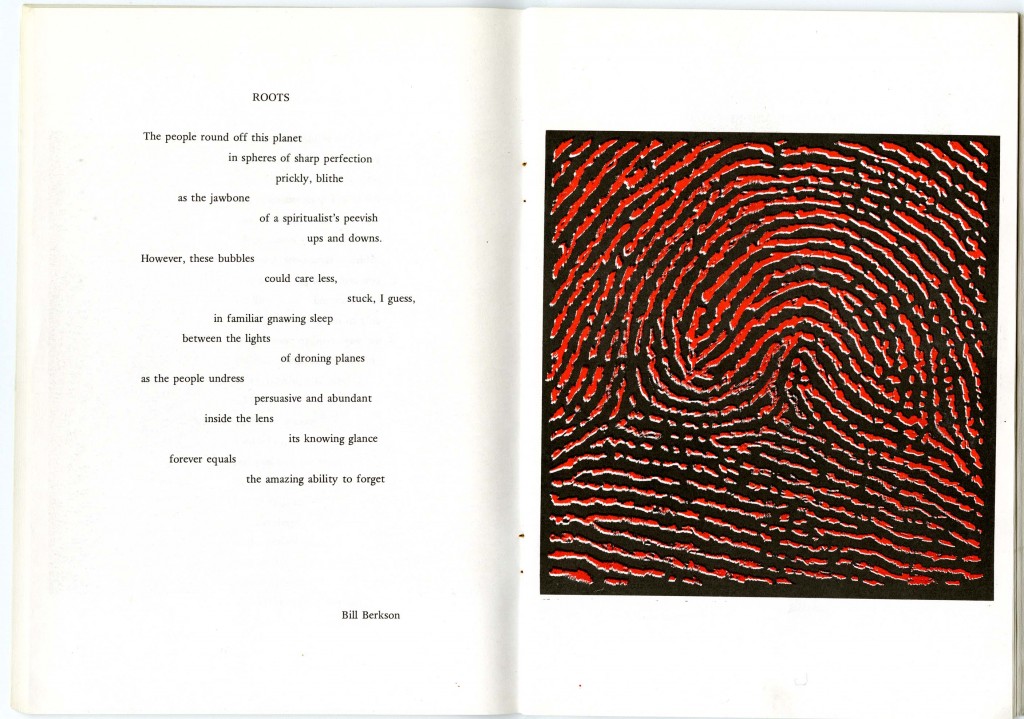

We are saddened to learn that Bill Berkson died last Thursday in San Francisco at the age of seventy-six. Berkson, a prolific American poet, art critic, and teacher, was also a muse, a world traveler, a lifelong gatherer and archivist, and to many of us in Archives and Special Collections at UConn, home of the Bill Berkson Papers, a literary giant, a generous collaborator and donor, and a friend.

We are saddened to learn that Bill Berkson died last Thursday in San Francisco at the age of seventy-six. Berkson, a prolific American poet, art critic, and teacher, was also a muse, a world traveler, a lifelong gatherer and archivist, and to many of us in Archives and Special Collections at UConn, home of the Bill Berkson Papers, a literary giant, a generous collaborator and donor, and a friend.

The Bill Berkson Papers comprise over one hundred linear feet of literary manuscripts, letters, drafts of poetry, notebooks, lecture notes, interviews, Big Sky Books and Press records, photographs, audio recordings, broadsides, rare publications, family papers, and personal ephemera.

Used by students and scholars alike, the archive spans from 1959 to 2016 and documents the poet’s extensive body of work, his collaborations in and among the realms of visual art, media, and literature, and his affinities with the poets and artists of the New York School.

Mr. Berkson wrote more than twenty collections of poetry, beginning in 1961 with “Saturday Night: Poems 1960-61.” His most recent book, “Invisible Oligarchs: Russia Notebook, January-June 2006 & After,” a travel journal, was published this year. He is survived by his wife, curator Constance Lewallen; son Moses Berkson and daughter Siobhan O’Hare Mora Lopez, from his first marriage, to Lynn O’Hare Berkson; stepchildren Jonathan Lewallen and Nina Lewallen Hufford; and six grandchildren.

According to San Francisco Chronicle, donations in Mr. Berkson’s name may be sent to Foundation for Contemporary Arts and Poets in Need.

Finding the Artist in His Art: A Week with the James Marshall Papers

By Julie Danielson

James Marshall (called “Jim” by friends and family) created some of children’s literature’s most iconic and beloved characters, including but certainly not limited to the substitute teacher everyone loves to hate, Viola Swamp, and George and Martha, two hippos who showed readers what a real friendship looks like. Since I am researching Jim’s life and work for a biography, I knew that visiting the James Marshall Papers in Archives and Special Collections at the University of Connecticut’s Northeast Children’s Literature Collection would be tremendously beneficial. In fact, Jim’s works and papers are also held in two other collections in this country (one in Mississippi and one in Minnesota), which I hope to visit one day, but I knew that visiting UConn’s Archives and Special Collections  would be especially insightful, since Jim made his home there in Mansfield Hollow, not far at all from the University. Indeed, I spent my evenings, as I wanted to maximize every possible moment during my days for exploring the collection, talking to people there in Connecticut who knew and loved Jim, including his partner William Gray, still living in the home they once shared.

would be especially insightful, since Jim made his home there in Mansfield Hollow, not far at all from the University. Indeed, I spent my evenings, as I wanted to maximize every possible moment during my days for exploring the collection, talking to people there in Connecticut who knew and loved Jim, including his partner William Gray, still living in the home they once shared.

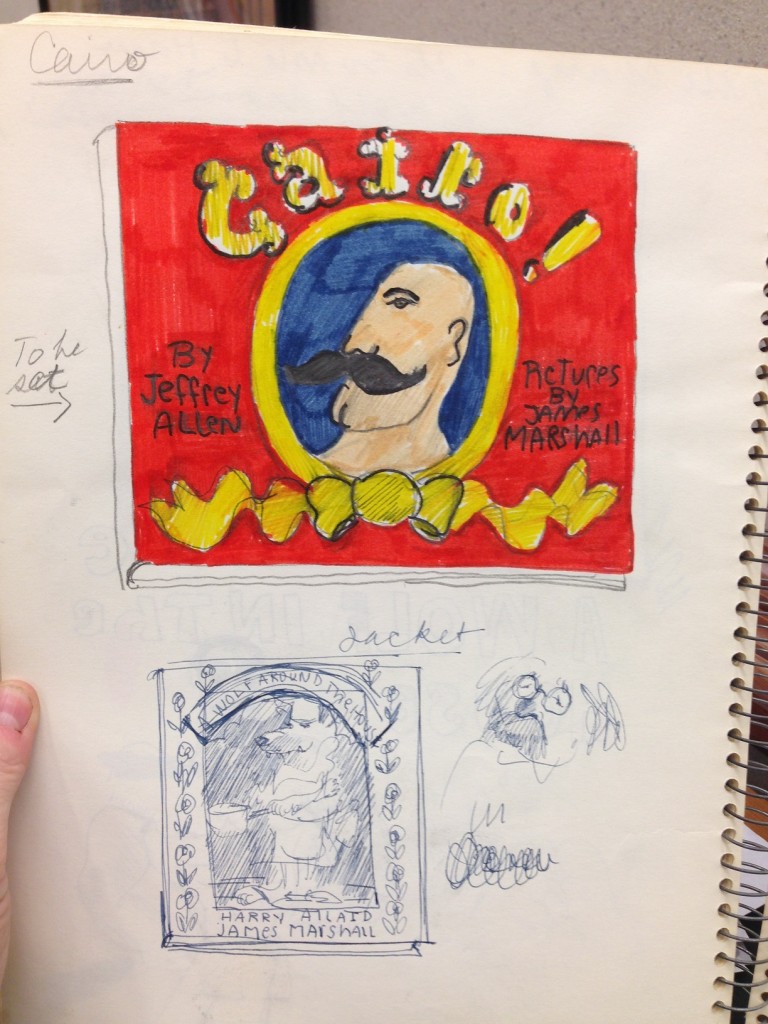

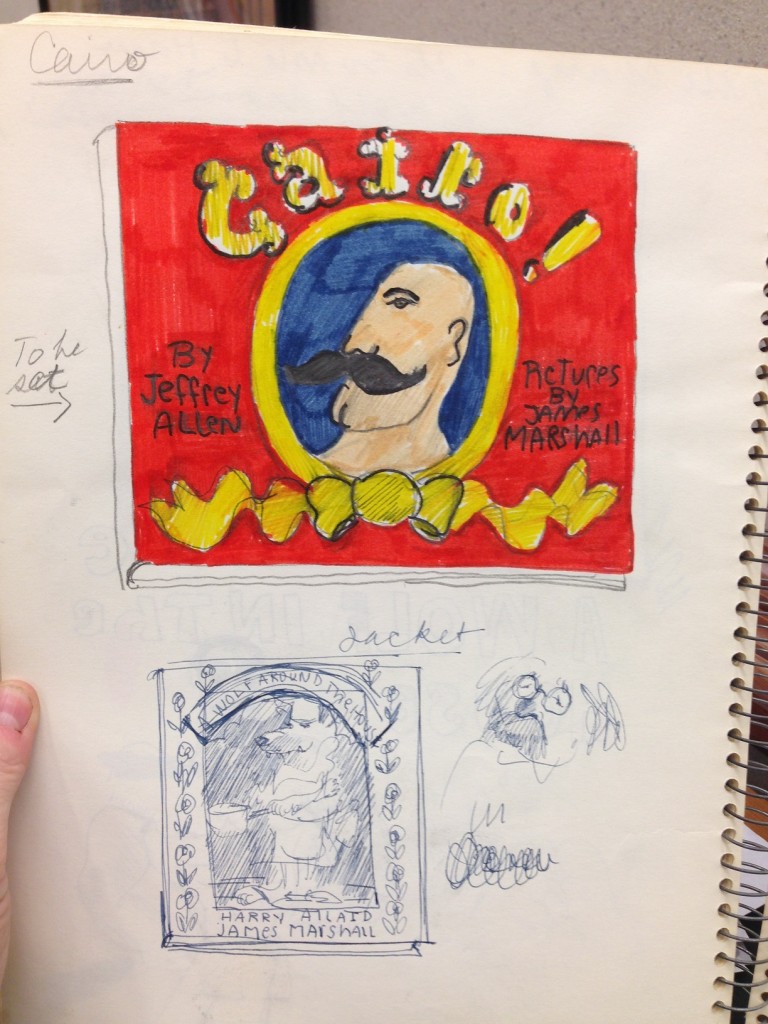

The collection is vast and impressive, just what a biographer needs. I had five full days, thanks to the James Marshall Fellowship awarded to me, to explore the archives and see, up close, many pieces of original artwork, as well as a great deal of his sketchbooks. I saw manuscripts, sketches, storyboards, jacket studies, character studies, preliminary drawings, dummies, proofs, original art, and much more from many of Jim’s published works, including a handful of his early books — It’s So Nice to Have a Wolf Around the House, Bonzini! The Tattooed Man, Mary Alice, Operator Number 9, and more. To see sketches and art from his earlier books was thrilling, because I’m particularly fond of many of those titles. (Bonzini!, I learned in the sketchbooks, was originally titledCairo.) Also on hand in the collection are sketches and art from his more well-known books, as well as books published at the end of his career (he died in 1992), including the popular George and Martha books and Goldilocks and the Three Bears, which received a 1989 Caldecott Honor. Read more…

Finding the Artist in His Art: A Week with the James Marshall Papers

By Julie Danielson

James Marshall (called “Jim” by friends and family) created some of children’s literature’s most iconic and beloved characters, including but certainly not limited to the substitute teacher everyone loves to hate, Viola Swamp, and George and Martha, two hippos who showed readers what a real friendship looks like. Since I am researching Jim’s life and work for a biography, I knew that visiting the James Marshall Papers in Archives and Special Collections at the University of Connecticut’s Northeast Children’s Literature Collection would be tremendously beneficial. In fact, Jim’s works and papers are also held in two other collections in this country (one in Mississippi and one in Minnesota), which I hope to visit one day, but I knew that visiting UConn’s Archives and Special Collections would be especially insightful, since Jim made his home there in Mansfield Hollow, not far at all from the University. Indeed, I spent my evenings, as I wanted to maximize every possible moment during my days for exploring the collection, talking to people there in Connecticut who knew and loved Jim, including his partner William Gray, still living in the home they once shared.

The collection is vast and impressive, just what a biographer needs. I had five full days,  thanks to the James Marshall Fellowship awarded to me, to explore the archives and see, up close, many pieces of original artwork, as well as a great deal of his sketchbooks. I saw manuscripts, sketches, storyboards, jacket studies, character studies, preliminary drawings, dummies, proofs, original art, and much more from many of Jim’s published works, including a handful of his early books — It’s So Nice to Have a Wolf Around the House, Bonzini! The Tattooed Man, Mary Alice, Operator Number 9, and more. To see sketches and art from his earlier books was thrilling, because I’m particularly fond of many of those titles. (Bonzini!, I learned in the sketchbooks, was originally titled Cairo.) Also on hand in the collection are sketches and art from his more well-known books, as well as books published at the end of his career (he died in 1992), including the popular George and Martha books and Goldilocks and the Three Bears, which received a 1989 Caldecott Honor.

thanks to the James Marshall Fellowship awarded to me, to explore the archives and see, up close, many pieces of original artwork, as well as a great deal of his sketchbooks. I saw manuscripts, sketches, storyboards, jacket studies, character studies, preliminary drawings, dummies, proofs, original art, and much more from many of Jim’s published works, including a handful of his early books — It’s So Nice to Have a Wolf Around the House, Bonzini! The Tattooed Man, Mary Alice, Operator Number 9, and more. To see sketches and art from his earlier books was thrilling, because I’m particularly fond of many of those titles. (Bonzini!, I learned in the sketchbooks, was originally titled Cairo.) Also on hand in the collection are sketches and art from his more well-known books, as well as books published at the end of his career (he died in 1992), including the popular George and Martha books and Goldilocks and the Three Bears, which received a 1989 Caldecott Honor.

To hold Jim’s original watercolors in hand is something I will never forget; as a fan of his books, I admit to getting a bit misty-eyed on more than one occasion (happy cries, to be sure). Seeing his artwork and sketches up close also afforded me rare insight into his unique talents as a children’s book illustrator, his process as an artist, his work ethic as a whole (he diligently worked and repeatedly re-worked the artwork that, in its final form, communicated an unfussy, uncluttered, and perfectly delightful simplicity) , and even his personality. This goes a long way in informing a biographer about her subject, and for that I am grateful.

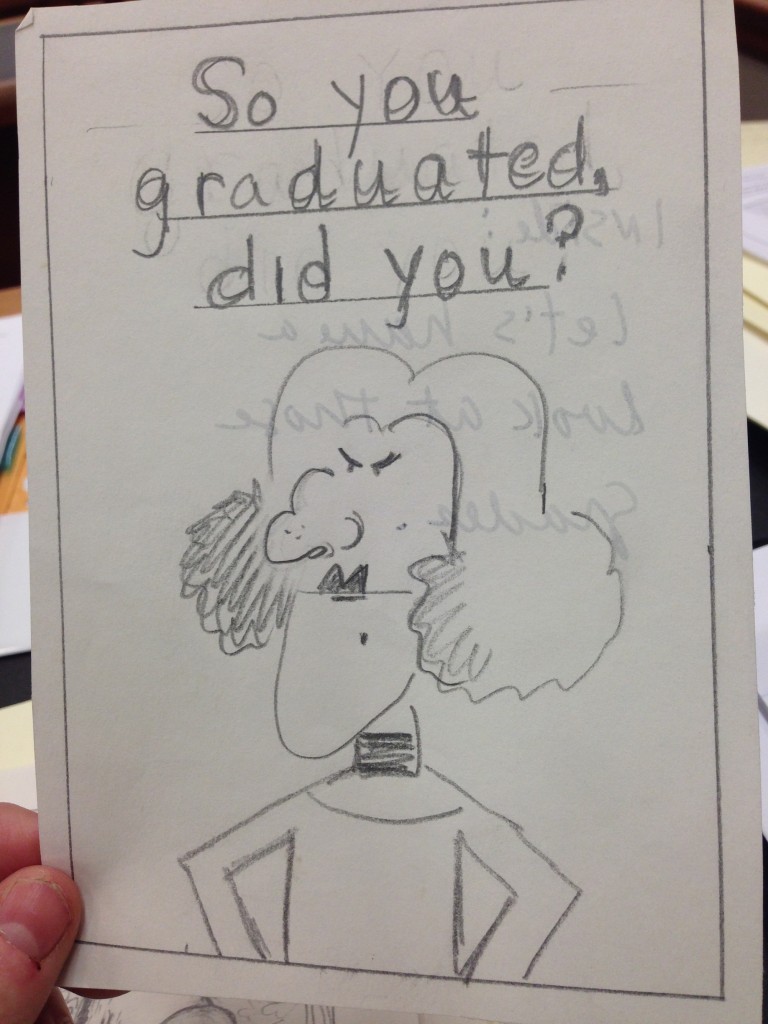

The collection also includes many of Jim’s unpublished works, including story ideas for the George and Martha books. (Readers never got to read stories about a sack race, football, fishing, and more.) There are also incomplete short stories, art for greeting cards (how I wish the one pictured here were available today; inside, it was to say “let’s have a look at those grades”),  many unidentified sketches, and much more. These unpublished works, as well as the series of sketchbooks available in the collection—there are a whole host of sketchbooks featuring both published and unpublished works—tell me a great deal about how Jim approached his work. For one, he always did so with a deep and abiding respect for children, which is my favorite aspect of his work. Never did he talk down to child readers. As Maurice Sendak wrote about Jim in an item in the collection, “never condescending to the child, allowing for freshness—sometimes rudeness—of the child’s genuine mind and heart.” In many of his sketchbooks, he also made detailed notes (illustrated, of course) about his days – what he did and whom he saw. These are intermingled with notes about book ideas. Needless to say, this is pure gold for a researcher/biographer, as are the personal papers in the collection. This includes some correspondence, an undated music book (Jim studied the viola before entering into the field of children’s books), his Caldecott Honor citation, and more.

many unidentified sketches, and much more. These unpublished works, as well as the series of sketchbooks available in the collection—there are a whole host of sketchbooks featuring both published and unpublished works—tell me a great deal about how Jim approached his work. For one, he always did so with a deep and abiding respect for children, which is my favorite aspect of his work. Never did he talk down to child readers. As Maurice Sendak wrote about Jim in an item in the collection, “never condescending to the child, allowing for freshness—sometimes rudeness—of the child’s genuine mind and heart.” In many of his sketchbooks, he also made detailed notes (illustrated, of course) about his days – what he did and whom he saw. These are intermingled with notes about book ideas. Needless to say, this is pure gold for a researcher/biographer, as are the personal papers in the collection. This includes some correspondence, an undated music book (Jim studied the viola before entering into the field of children’s books), his Caldecott Honor citation, and more.

A relatively recent addition to the collection is one that was added after the 2012 death of legendary author-illustrator Maurice Sendak. Jim and Maurice were close friends, and included in this series in the collection is a birthday book Jim once made for Maurice; books he gifted and autographed to Maurice; some of Jim’s original art, which Maurice had purchased; and more. This series told me a lot about the abiding friendship between the two, which is quite moving. It included a wooden box that contains some of Jim’s brushes and his glasses. (I find myself having to constantly remind my twelve-year-old daughter to clean her glasses, but I was able to tell her later that day, “you’re in good company. The brilliant James Marshall had smudges on his glasses as well.”) Also included is a letter from Maurice, noting the contents of the wooden box. In this letter he talks about being with Jim in July of 1992; this was about three months before Jim’s death from AIDS. Jim, unresponsive, was on his first day of morphine. “His last words … to me,” Maurice wrote, “on the telephone [had been] ‘Lovely, Loyal Maurice.’” Maurice, in fact, drew Jim as he was dying, though these drawings are not in the collection.

On my last day in Archives and Special Collections, I watched video footage of Jim speaking in one of Francelia Butler’s children’s literature courses at UConn. (Also included in the collection are Jim-related items in the Francelia Butler Collection, which were extremely helpful for my project.) It is a lecture that is, at turns, laugh-aloud funny, incisive, and smart. Jim was deliciously opinionated about others’ books. I now know first-hand how much biographers can learn from seeing video footage or hearing audio of their subjects. It was the first time I’d seen (or even heard) Jim speak.

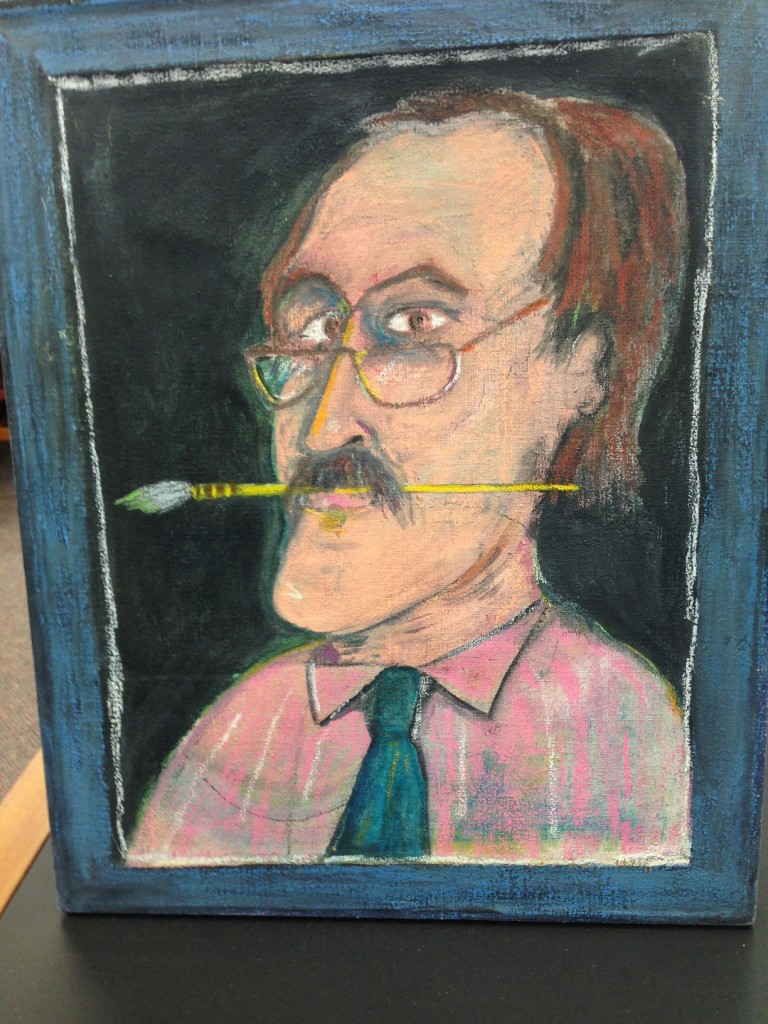

I’ll close with this rare self-portrait (on canvas), which curator Kristin Eshelman thought I’d want to see. Kristin said that Jim had painted it for his mother, with whom, I have learned, he had an affectionate yet probably complicated relationship. (He adored her and remained close to her all his life, yet she refused to accept that he was gay. She was strong-willed, and I quickly discovered that one cannot hear stories about Jim without also often hearing about her.) I love this painting. It’s happy (the pink!), a bit unsettling (note the placement of his right eye), and gloriously weird, all at once. Jim stares at us, in between brush strokes. I like to imagine he’s still here, looking askance at us just like this. With the same “genuine mind and heart” he acknowledged in his child readers.

I’ll close with this rare self-portrait (on canvas), which curator Kristin Eshelman thought I’d want to see. Kristin said that Jim had painted it for his mother, with whom, I have learned, he had an affectionate yet probably complicated relationship. (He adored her and remained close to her all his life, yet she refused to accept that he was gay. She was strong-willed, and I quickly discovered that one cannot hear stories about Jim without also often hearing about her.) I love this painting. It’s happy (the pink!), a bit unsettling (note the placement of his right eye), and gloriously weird, all at once. Jim stares at us, in between brush strokes. I like to imagine he’s still here, looking askance at us just like this. With the same “genuine mind and heart” he acknowledged in his child readers.

Julie Danielson holds an MS in Information Sciences and blogs about picture books at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast. The co-author of Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, she also writes a weekly column and conducts Q&As for Kirkus Reviews. She reviews picture books at BookPage and has written for the Horn Book and the Association for Library Services to Children. She has been a judge for the Bologna Ragazzi Awards in Italy, as well as the Society of Illustrators’ Original Art Award, and she is a Lecturer for the University of Tennessee’s Information Sciences program. Ms. Danielson was awarded a James Marshall Fellowship in 2015. The James Marshall Fellowship is awarded biennially by Archives and Special Collections to a promising author and/or illustrator to assist with the creation of new children’s literature. Support is provided for research in the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection for the creation of new text or illustrations intended for a children’s book, magazine, or other publication.

Looking Back and Looking Forward

No matter where your political allegiance lies it is impossible to deny the significance of Hillary Clinton’s ascent towards the Democratic nomination for president. It is also a time to acknowledge the importance of women who came before her. Through the generous donation and support of one of her family members we are lucky to have the personal and professional papers of one such woman, Vivien Kellems, in our care.

Born in 1896 Kellems (or ‘Viv’ as we fondly refer to her) is a gem of Connecticut women’s history. She owned and dedicatedly operated Kellems Cable Grips company first out of Westport and then Stonington. The company produced and sold her brother Edgar’s invention for stringing electrical wiring. She ran for senate a total of four times in the years 1950, 1956, 1962 and 1965. She also made a run for governor of Connecticut in 1954. Although she was unsuccessful in her campaigns, Kellems was in no way defeated.

Believing the tax system to be unfair both to small business and unmarried individuals Vivien Kellems very publicly fought for tax reform; publishing a book on the subject in 1952 “Toil, Taxes and Troubles”. She also headed the formation of a group of like-minded individuals dubbed ‘The Liberty Belles’. Yet another campaign for Vivien was a call for voting reform – deeming it unfair Americans be forced to vote along party lines only and not for individual candidates. In demonstration of her protest Kellems camped out in a voting booth for hours only having to leave when she fainted.

Currently her papers including family, business and political correspondence are being thoroughly processed and digitized. You’re invited and encouraged to keep checking in on the progress through this link. As we celebrate the accomplishments of our contemporaries let’s also remember that women have always been bold and remarkable.

Oh and Viv also has pretty fabulous handwriting.

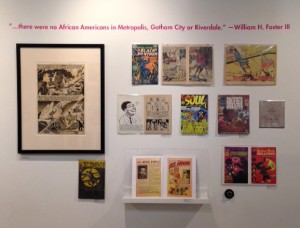

Our Comics, Ourselves on Exhibit

The Archives & Special Collections at the University of Connecticut will host the first traveling installment of the exhibition Our Comics, Ourselves co-curated by Jan Descartes and Monica McKelvey Johnson. Premiering at the Interference Archive in Brooklyn, NY in January of 2016, this exhibition featured comics selections from the Interference Archive collections as well as private collections on loan. The exhibition includes comic books, graphic novels, DIY comics, and various comics paraphernalia primarily from the United States, 1945 to present. The works range from autobiographical to sheer fantasy, and explore feminism, abortion, racism, cultural identity, social activism, veterans of war, sexual abuse, immigration, public health, civil rights, gender and sexual identity, and more.