by Richard Telford

Author’s Note: Though the product of many hours of research, writing, and revision, this chapter is nevertheless a draft; it will be subject to revision as the larger book in which it will appear takes shape. This chapter follows the book’s prologue and first chapter, both of which provide important context for my writing here. This is the sixth chapter to be published on this site. The first three, published this past winter, were later chapters of the book, chronicling the Teales’ loss of their son David during wartime service in 1945. Those chapters can be accessed here. As of now, I do not plan to pre-publish additional chapters. I welcome critical response to all of this work, either in the comment section of this site or through direct e-mail. I am grateful to the Archives and Special Collections staff for providing me the opportunity to share this work, and to the Woodstock Academy Board of Trustees for awarding me a sabbatical for the 2016-2017 school year. Contextual information about the project and manuscript can be found here.

Chapter 2: Nobody and Somebody: The Loving Ways of Lone Oak

It was a warm, or fairly hot day in spring—the grass was turning green, and the budding trees sent a pleasant odor thru the evning air. The patient lowing of the cattle in the lane, was distinctley heard above the scuffling on the roosts in the chicken coop; the grunting and squeeling from the pig-pen, and the blating of the hungry calves. The sparrows churped loudly from the Tamarack in frunt of the house and from across the road in the woods came the song of a whip-poor-will and numerous other songsters….These sights and sounds—usually interesting to any city boy, were especially so to me.[i]

Edwin Way Teale, Tails of Lone Oak, 1908

On both sides I am descended from a long line of those who were not the kind of folk whose names name-droppers drop. They were not the kind to provide ammunition for excessive boasting. They were, in the main, common people. But the world was not made worse because they lived in it.[ii]

Edwin Way Teale, autobiography draft, July 27, 1974

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you – Nobody – too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Don’t tell! they’d advertise – you know!How dreary – to be – Somebody!

How public – like a Frog –

To tell one’s name – the livelong June –

To an admiring Bog![iii]

Emily Dickinson, poem 288

The old man stood atop the open platform of the Furnessville train depot, the right side of his face lit by “station lamps gleaming on the snow,” the left by a kerosene lantern held high, as five-year-old Edwin stepped from the train with Clara and Oliver following at his heels. The Teales had arrived for a week-long Christmas visit to Lone Oak. It was the earliest such visit to remain forever etched in Edwin’s memory. The old man, “bundled in a fur coat until he resembled a great grizzly bear,”[iv] was Edwin Franklin Way, Clara Teale’s father and Edwin’s grandfather. Ed Way’s roots, like those of his bride, were eastern. His father, Hiram, a New York lumberman, had moved his family west during the pioneer days of the mid-nineteenth century, settling in Porter County, Indiana in 1855[v]—fourteen years prior to the start of the family peregrinations chronicled by Laura Ingalls Wilder. At the time, Ed Way, the second of five children, was twelve. When he turned eighteen at the outset of the American Civil War, he “enlisted as a private in the Fourth Indiana Artillery, attached to the Army of the Cumberland,”[vi] later fighting in several major battles. The first, the October 1862 Battle of Perryville, expelled the Confederate Army of General Braxton Bragg from Kentucky, forcing an overnight retreat through the Cumberland Gap into Tennessee. Three months later, the forces met again on New Year’s Eve day in the battle of Stones River, also called the Second Battle of Murfreesboro. Of the major battles of the American Civil War, the casualty percentage at Stones River was second only to that of Gettysburg.[vii] Ed Way was amongst the seriously wounded at Stones River and was discharged for disability and sent home to recuperate. In 1865 he reenlisted, this time with the ninth Illinois Cavalry, and served out the remainder of the war.[viii] Afterward, he used his Army pension to buy a homestead at the edge of the Indiana dunes.

Exiting the train platform on that bitter, Solstice-dark December night in 1904, the Teales packed themselves into the waiting bob-sled that would hurry them out to Lone Oak. Edwin later recalled how “the horses stamped and jingled their sleigh-bells and sent out clouds of silver steam into the cold night air.”[ix] At the clean, modest farmhouse, the young boy’s gaze was drawn first to the freshly-cut Christmas tree “trimmed with polished apples, strings of popcorn, paper decorations and marshmallow fish.” These fish, he recalled later, “had a flavor which haunted me for years afterwards.”[x] But his gaze and his admiration shifted quickly to the loving pair who would remain at the center of all of his later Lone Oak exploits, a pair “as remarkable as the dune country itself, as remarkable as the varied fields of the farm from which they had so long wrung a living.”[xi] That winter visit, and another during the summer that followed, preceded his matriculation at the Woodland School in Joliet.[xii] Thus, these visits comprised an early, critical education for Edwin, an education that contrasted sharply and restoratively with that of the twig-bending kind to which he had grown accustomed at home. It was palliative and healing, an antidote both for the trials of his earliest years and for the “new, strange world” of formal schooling still to come—a sphere whose governors often showed little patience for a mind “like a butterfly flitting about in a field of flowers.”[xiii] In a “world [that] was so full of interest,” he wrote in his unpublished autobiography, “I could not concentrate on any one thing.”[xiv] “It was not that I was dull witted,” he observed elsewhere. “It seemed more that my mind was too lively.”[xv] At Lone Oak, Edwin’s lively mind could flit unfettered. At Lone Oak, he could escape the disapprobation and shame that haunted his childhood. At Lone Oak, his grandparents set him free in nature, “a liberal mother who gave me room to expand, freedom to seek my own level, time to think my own thoughts.”[xvi]

* * * * * * *

Gramp Way, Edwin remarked in Dune Boy, “was probably not a very efficient farmer.” He paid little attention to “proper soils or [crop] rotation.”[xvii] In farming and in life he eschewed routine; it “galled his spirit.”[xviii] For Edwin, this was an endearing quality: “Gramp was one of those unschooled men whose minds are not molded to conventional patters. He was himself, never anyone else.”[xix] Despite a lack of formal schooling, Gramp’s was a percipient mind that expressed itself in tenaciousness and ingenuity, in wit and compassion. He was, Edwin reflected, “a living refutation of that specious fallacy of the literate—the belief that illiteracy and ignorance are synonymous.”[xx] Though he had never read a book before marriage, he became, through his wife’s tutelage, an engaged reader by the time Edwin made his holiday pilgrimages to Lone Oak. In a journal he kept during the summer of 1911, Edwin noted, “…gramp’s deep in the mistarys of ‘The Silver Hord,’” Rex Beach’s popular 1909 novel of the Pacific fisheries. “I hear grampa exclaming from the corner couch,” Edwin continued, “so I suppose he has found an extra instering part….”[xxi] Edwin’s profound struggles with spelling as a child—at which he later poked fun both in Dune Boy and his unpublished autobiography—likely deepened his capacity in later reflection to fully discern Gramp’s vigorous if unschooled intellect. Despite his proclivity to “blithely ignore the dictates of Webster and the grammarians,”[xxii] Ed Way sacrificed much to send his three daughters through college. He knew the pioneer landscape was giving way to a new, more educated world in which tenacity alone might not ensure one’s future.

In Edwin’s view, Gramp’s love of subtle humor was the greatest expression of his keen mind. This humor, most conspicuous in the stream of aphorisms the older man interjected into daily conversation, was a staple of Lone Oak life. Edwin recorded many of these aphorisms both in Dune Boy and in his autobiography notes. Waking from an after-dinner catnap, Gramp would proclaim, “Don’t know what you folks expect to do—but I know I’m about prepared to rear and tear and mount!” After this, he would “saunter off to bed.”[xxiii] Of his daily financial plight, he’d remark, “If the whole meetin’ house was for sale fer a cent I couldn’t buy a shingle today!”[xxiv] When guests arrived, he’d quip, “Sit down boys, just as cheap as standing up!”[xxv] Growing impatient over the slow preparation of a meal, he’d say “Today, tomorrow and the next day will be three days since I had anything to eat.”[xxvi] Or, “I don’t git hungry very often. But when I do ‘ts about now.”[xxvii] Once, when a new pair of shoes had given him blisters, he declared, “I must be like a Jay bird with my longest toe behind.”[xxviii] About a jacket Gram had sewn for him, he complained, “Say mother, ye put these pockets in my jacket so high I had to git up on a stump to pull out my handkercher.”[xxix] And he reveled in the story of a young female school teacher who boarded briefly at Lone Oak. As the three ate breakfast one morning, Gram said, “Sometimes I wish you’d cut your whiskers off!” Gramp held his tongue, but the young lady responded, “I think a kiss without a mustache is like an egg without salt!” Gramp retold the story often.[xxx] “The ax and the hoe and the pitchfork,” Edwin reflected later, “the years of toil which had bowed his shoulders and enlarged the knuckles of his hands, had never dulled his sense of humor nor his love of the joke.”[xxxi] For Ed Way, humor released the injurious steam of daily struggle. It reflected his desire “to ‘camp out’ at home,”[xxxii] to live contentedly in the present, imprisoned neither by past regrets nor dim future prospects.

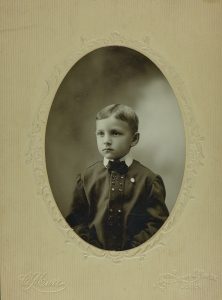

Edwin Way Teale with his maternal grandparents Edwin F. and Jemima Way at Lone Oak, their Indiana farm, circa 1916-1918.

Gramp Way’s easygoing nature sometimes belied the fierceness of spirit that allowed him to eke a living from “an uncompromising tract” of land and to combat the steady stream of hucksters and thieves who plied the uneducated country folk at the edge of the dunes. Once, two men arrived at Lone Oak, a pair of “crooks [who] tried to get Civil War veterans to mortgage farms for $500 for [a] pair of glasses to keep Gramp from going ‘blind before morning.’” Gramp surreptitiously sent Edwin outside to let air out of the front tire of their car and to bring in cordwood. Gramp then “use[d] [a] stick on [the] crooks” and sent them hastily on their way.[xxxiii] Another time, a wandering tramp offered to chop stove kindling in exchange for a meal. Gramp assented and went back to his own work, realizing shortly afterward that the tramp had “shouldered the ax and set off at a trot down the road.” This prompted Gramp to set off “in hot pursuit.” When caught and confronted, the tramp dropped the ax and fled for the woods. Later, Gram expressed her dismay that the tramp might have killed Gramp, to which he replied, “What d’ y’ think I’d a bin doin’ about thet time?”[xxxiv]

Gramp’s earliest experiences on the Indiana frontier and his wartime service provided rich fodder for storytelling, an act bolstered by his “gift for the colorful phrase, the humorous twist, [and] the original observation.”[xxxv] On late summer evenings, sitting by “a smudge fire which kept the mosquitoes away,” Gramp wove elaborate tales “of the early days, the Indians, the wolves, the deer, the struggles of the pioneers.” At the start of the twentieth century, the dune edges had been converted to farmland “devoted to corn and oats, melons and potatoes,” but Gramp could remember the time when forests still blanketed the landscape. For Edwin, those stories “were like windows looking back into a glorious and adventurous past.”[xxxvi] Another such window lay in the southwest corner of Lone Oak, in a small “marshland ‘island’ where Gramp’s cows stood in the shade and flicked away the flies…during the hottest hours of the August noontide.”[xxxvii] Local lore told of this island as a former battleground of warring native tribes. From the “sand which lay beneath the sparse grass” of the island, young Edwin unearthed “a storehouse, a museum, of Indian implements…more than 100 arrowheads, spearheads and tomahawk-heads.” The plowing of the neighboring Gunders’ field yielded up similar treasures. It is no wonder that Edwin saw Lone Oak as “a sort of Never-Never-Land come true,” and no wonder that, in the confines of Joliet and under his mother’s critical eye, he would “cross off the days on the calendar and count the number remaining before the next vacation when I would return again to the green pastures of that Indiana farm.”[xxxviii]

* * * * * * *

In late August of 1852, three years before Hiram Way would move his family to the edge of the Indiana dunes, Jemima George was born in Ogdensburg, New York, spending “her early years near the banks of the St. Lawrence River.” Her father, “a prosperous masonry contractor” who was “engaged in building large churches in the region,” was able to send her to “a select seminary for young ladies” in Ogdensburg for 1865 and 1866.[xxxix] Henry George’s health failed in 1867, however, and with it his finances, so the family headed west in search of opportunity and healing, possibly encouraged by the prospects of “the prairie cure,” the widely-held belief in the power of “the clear dry air of the Midwest to allay” tuberculosis[xl] and other ailments. By the spring of 1867, they arrived in Morgan’s Sidetrack—later renamed Furnessville—and settled on a farm several miles from Lone Oak. “For the young girl,” Edwin noted, “this swift change…was like a plunge from daylight into darkness.”[xli] Jemima “floundered about” for several months, feeling “bewildered and uncertain, shy and misunderstood.”[xlii] Then she met Ed Way, who, “at the time, possessed nine white shirts”—a potent if amusing symbol of his post-war prosperity. For “state occasions,” he still donned the brass-buttoned blue Army overcoat he had brought home from the war.[xliii] He cut an impressive and benevolent figure, and Jemima, now 16, and Ed, now 25, were married on November 12, 1867.[xliv]

In post-Civil War pioneer society at the ede of the Indiana dunes, it was “the harder qualities of mind and character that [were] at a premium,” Edwin wrote later. “Men and women, struggling desperately to make ends meet, [were] like tightrope-walkers who [could not] forget for a moment the business of preserving their lives.”[xlv] Despite her initial shock and floundering, Jemima Way adapted quickly to the rigors of her newly-entered world, a process accelerated by her father’s death in 1869. Still, the physical and emotional rigors of frontier life cut deeply. On Christmas Day 1868, just over a year into marriage, she gave birth to a daughter, Alice. Alice lived only a few hours, and “as often was the custom in those early days—a grave was dug under an apple tree, about 2 rods from the house and a little home-made wooden box containing the infant was lowered into it.”[xlvi] Clara Teale later remembered how “For many years we younger children planted flowers and cut grass on that little spot of ground.”[xlvii] Ed and Jemima went on to have four more children: Clara Louise, in 1870; Allan Henry, in 1874; Winnifred Margaret, in 1880; and Blanche Elizabeth, in 1885. Tragedy came again for the Ways when Allan, who had been diagnosed with an enlarged heart, died shortly after the celebration of his twenty-first birthday. At the time, he was studying law with a Judge in Valparaiso; it was a halting end to a once-bright future.[xlviii] Such early deaths were common enough in a time when “it was the unusual thing for any farmer’s wife to have a doctor for childbirth”[xlix] and malaria was so rampant “that a little dish of quinine was placed on the table and every member of the family had to dip out a quantity and swallow it at breakfast-time.”[l] Still, the expectation of such loss did little to temper its sting.

Jemima Way spent her days “bending over her scrub-board or laboring at the churn,” often “wracked by chills and fever.” When farm help was scant, “she hoed in the blistering sun”[li] and took on nearly any other work that needed doing, often singing “old folksongs and ballads from England” to help pass the long hours.[lii] She rarely complained, but there were times during Edwin’s boyhood visits when Gramp would pull the boy aside and say, “Mother’s got alum on ‘er tongue this mornin’. Better steer clear o’ the’ kitchen.”[liii] Of these moments, Edwin wrote poignantly, “Fatigue is Life’s great poison.”[liv] Still, he noted further, “This hard labor which was her lot never broke her spirit.”[lv] A chance event that occurred when her children were young helped nurture and sustain that spirit; the effects of that event would ripple over decades, shaping the lives of a host of passers-through at Lone Oak, none more than the boy who “whirled like a satellite” around Ed and Jemima Way “from June to September in the golden days of summer and youth.”[lvi]

Lone Oak was located in the center of Pine Township, in Porter County. Sometime during the 1880s, “The Township trustees purchased a set of 140 of the world’s classic books of history and literature.” The books, “bound in leather and housed in a special bookcase,” were to serve as a public library.[lvii] Despite her constant toil at Lone Oak, Gram never forsook her educated roots. She had carried the intellectual flame kindled at Ogdensburg to the Indiana frontier, and there she had banked it beneath the ash of daily struggle, refusing to let it die. The Township library provided fuel for her inward fire, and the trustees’ selection of Jemima Way as its custodian, and Lone Oak as the site where it would be housed, yielded a cascade of effects they could never have anticipated. Throughout the decades that followed, Gram Way “read aloud every one of the millions of words” entrusted to her, over and over again, not just to her own family but to anyone who would listen. Long before young Edwin’s arrival at Lone Oak, “neighbors and hired men from near-by farms used to stroll over after the chores were done…stretching out on the front porch, puffing silently at their pipes” as Gram sat beside a kerosene lamp “inside the screen door…[and] read on and on, her expressive voice rising with the exciting passages.”[lviii] It was one of a host of Gram’s “nameless, unremembered acts/Of kindness and of love”[lix]—love for her family and for neighbors, and love for the power of the written word, a power that could both validate and transcend daily human struggle.

The north view of the farmhouse at Lone Oak. Edwin F. Way is seated in a rocking chair, reading in the breezeway.

Gram’s love of knowledge and the extraordinary value she placed upon the written word were not bound by her custodianship of the Pine Township library. “Possibly the greatest pleasure she had while living at Lone Oak,” Clara Teale recalled in the 1940s, “was her connection with the Grange…She wrote both prose and poetry for their programs.”[lx] She also wrote and published numerous articles for The Rural New Yorker, some of which were “reprinted in New York [City] papers.” Edwin recalled later how “she would write, by the light of an oil lamp,” despite her exhaustion of the day.[lxi] These articles, reflective of the time, were printed unsigned, rendering her a nameless voice from the country, at once somebody and nobody—a paradox driven home to her by events surrounding a particular article of which she was especially proud. After publication, she recopied its text, sent it to her only brother, and waited “anxiously for his reply.” When it came, he had written not with praise but doubt of her authorship: “Why did you tell me [that] you wrote that article? I read it some weeks ago in a New York City paper.” The slight “hurt her deeply,” as “she had thought above all people—he would be the one who would see its worth,”[lxii] and likewise recognize hers.

While her brother could not see the deep well of her talents, Edwin could; and for her beloved grandson, Jemima Way dipped that well even more deeply. During one of his earliest summer visits to Lone Oak, Edwin recalled, “She put me to sleep each night with a new installment of a continued story about the River Pixies,” a complex, extempore creation sprung from her imagination. Accompanied by the “chorus of the katydids and crickets swelling outside the bedroom window,” Gram sat nightly on the edge of Edwin’s bed and conjured “faint, long-ago images of little people, with peaked caps, running about the banks of a dark stream.”[lxiii] Those images “remain with me still,” he wrote nearly four decades later.[lxiv] Amidst the life-preserving desperations of frontier life, he reflected, “A sensitiveness to the color and poetry of Nature” was “unessential, excess baggage.”[lxv] In that world, the majority, Thoreau’s “mass of men…so occupied with the factitious cares and superfluously coarse labors of life,”[lxvi] spent their lives “stifling the desire for luxury.”[lxvii] Jemima George Way was an exception, and thus was she exceptional in her grandson’s memory. “It is only the rare and superlative character,” Edwin wrote, “who is able to retain the softer qualities, beneath his armor, in a world of constant struggle. This Gram did and she stands out in my mind as one of the indomitable, great women of my meeting.”[lxviii] Jemima Way not only retained such qualities but shared them freely: with family and neighbors, with farm hands and strangers, and with her beloved grandson, for whom her influence endured to his last days. She nourished Edwin’s acute sensitivities when it mattered most, when much of the world seemed bent on smothering them. She helped his emotional and intellectual waters find their level.

Reflecting on his childhood, Edwin understood fully how erratic the spotlight of memory could be, but he likewise understood how it was inevitably drawn to fixed points, to anchors, to holdfasts in the flood and ebb of life’s waters. Such were the memories of Gram and Gramp Way. Later, he came to associate these benevolent centers of his childhood orbits with three lines from Irish poet William Butler Yeats:

For life moves out of a red flare of dreams

Into a common light of common hours

Until old age brings the red flare again.[lxix]

Reflecting on these lines decades later, Edwin wrote, “Thus it was that my grandparents seemed to understand best of all, the world of dreams, of fantastic plans, of make-believe in which I spent so many hours.” “When we are young,” he continued, “we know least of all how different we are, or how different from the norm are those around us. It takes perspective to see ourselves in relation to the world at large. It was only after many years had passed that I understood how strange a boy I must have been or how unusual were the two who were my closest summer companions.”[lxx] Long after Gram and Gramp Way had returned to the earth they had spent their lives tending, Edwin took comfort in the fact that he had memorialized them through his writing. “Thinking of those golden duneland days,” he wrote in the spring of 1962, “I realize, with something of a start, that I am the only person in all the world who remembers them. Who remembers Lone Oak now? I alone. But in a way there are thousands more—all who have lived those days with Gramp and Gran in the pages of ‘Dune Boy.’”[lxxi] To the broader world, Ed and Jemima Way were nobody; to their friends and neighbors, they were somebody; to a strange, self-conscious, highly sensitive satellite of a boy, they were everybody.

Richard Telford has taught literature and composition at The Woodstock Academy since 1997. In 2011, he helped found the Edwin Way Teale Artists in Residence at Trail Wood program, which he now directs. He was a long-time contributing writer for The Ecotone Exchange. He was recently awarded a Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz Travel Grant by the University of Connecticut to support his work on a book about naturalist, writer, and photographer Edwin Way Teale. The Woodstock Academy Board of Trustees likewise granted him a sabbatical for the 2016-2017 academic year to support this work.

References

Civil War Trust, The. “Ten Facts: Stones River.” https://www.civilwar.org/learn/articles/10-facts-stones-river. Accessed 24 7 2017.

Dickinson, Emily. The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Ed. Thomas H. Johnson. Boston, London, New York: Little Brown and Company, 1960.

Goodspeed, Weston A., and Charles Blanchard, Eds. “Edwin F. Way.” Counties of Lake and Porter Indiana: Historical and Biographical. Chicago: F.A. Battey and Co., 1882.

Pryor, Elizabeth Brown. Clara Barton, Professional Angel. Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1987.

Teale, Clara Louise Way. Notes for Edwin Way Teale’s autobiography, Circa 1945-1950. Box 63, Folder 2170, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Clara Louise Way. Notes for Edwin Way Teale’s autobiography, Circa 1945-1950. Box 63, Folder 2188, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Days of Hearsay” chapter notes, drafts, 1974. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2167, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Days of Hearsay,” draft, 25-27 July, 1974. Most Complete Manuscript, undated. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2187, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy: The Early Years of a Naturalist. Lone Oak Edition. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1943, 1957.

Teale, Edwin Way. Edwin Way Teale’s Composition Book [Circa 1910-1912]. Box 85, folder 2664, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Memories of a Bent Twig” chapter notes, drafts, 1974 July 31. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2169, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “My Earliest Home” chapter notes, drafts, 1974 July 31. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2168, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. Tails of Lone Oak. 1908-9. Unpublished manuscript. Box 84, Folder 2585, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. The Trail Wood Journal, 1962-65, unpublished journal. Box 120, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Woodland Days” chapter notes, research, drafts of manuscript, correspondence, 1974 August 19. The Long Way Home (EWT’s autobiography). Box 63, folder 2170, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Teale, Edwin Way. “Woodland Days,” draft, 10-19 August, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187, Edwin Way Teale Papers 1799-1995, Archives and Special Collections, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

Thoreau, Henry David. Walden: or Life in the Woods. Ed. Edwin Way Teale. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1946.

Wordsworth, William. “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour, July 13, 1798.” Wordsworth’s Complete Poetical Works. Cambridge Edition. Ed. Andrew J. George. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1904. 91-3.

Yeats, William Butler. The Land of Heart’s Desire. Chicago: Stone & Kimball, 1894.

Notes:

[i] Teale, Edwin Way. Tails of Lone Oak. 1908-9. Chapter 1. Box 84, Folder 2585.

[ii] Teale, Edwin Way. “Days of Hearsay,” draft, 25-27 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 5-6

[iii] Dickinson, Emily. The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Ed. Thomas H. Johnson. Boston, London, New York: Little Brown and Company, 1960.

[iv] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 7

[v] Goodspeed, Weston A., and Charles Blanchard, Editors. “Edwin F. Way.” Counties of Lake and Porter Indiana: Historical and Biographical. 398

[vi] Ibid. 398

[vii] Civil War Trust. Ten Facts: Stones River. Accessed 24 7 2017. https://www.civilwar.org/learn/articles/10-facts-stones-river

[viii] Goodspeed, Weston A., and Charles Blanchard, Editors. “Edwin F. Way.” Counties of Lake and Porter Indiana: Historical and Biographical. 398

[ix] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 7

[x] Ibid. 8

[xi] Ibid. 12

[xii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “My Earliest Home.” Box 63, folder 2168.

[xiii] Teale, Edwin Way. “Woodland Days,” draft, 10-19 August, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 1,5

[xiv] Ibid. 5

[xv] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Woodland Days.” Box 63, folder 2170.

[xvi] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Memories of a Bent Twig.” Box 63, folder 2169.

[xvii] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 17

[xviii] Ibid. 17

[xix] Ibid. 16

[xx] Ibid. 16

[xxi] Teale, Edwin Way. Edwin Way Teale’s Composition Book [Circa 1910-1912]. Box 85, folder 2664

[xxii] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 16

[xxiii] Teale, Clara Louise Way. Notes for Edwin Way Teale’s Autobiography, Circa 1945-50. Box 63, folder 2170.

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 141

[xxviii] Teale, Clara Louise Way. Notes for Edwin Way Teale’s Autobiography, Circa 1945-50. Box 63, folder 2170.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 14

[xxxii] Ibid. 17

[xxxiii] Teale, Edwin Way. Undated notes. “Woodland Days.” Box 63, folder 2170.

[xxxiv] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 20

[xxxv] Ibid. 14

[xxxvi] Ibid. 11

[xxxvii] Ibid. 29

[xxxviii] Ibid. 10

[xxxix] Ibid. 20

[xl] Pryor, Elizabeth Brown. Clara Barton, Professional Angel. 67

[xli] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 21

[xlii] Ibid. 21

[xliii] Ibid. 21

[xliv] Teale, Clara Louise Way. Notes for Edwin Way Teale’s autobiography, Circa 1945-1950. Box 63, folder 2188.

[xlv] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 25

[xlvi] Teale, Clara Louise Way. Notes for Edwin Way Teale’s autobiography, Circa 1945-1950. Box 63, folder 2188.

[xlvii] Ibid.

[xlviii] Ibid.

[xlix] Ibid.

[l] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 21

[li] Ibid. 21

[lii] Teale, Edwin Way. “Days of Hearsay,” draft, 25-27 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 5

[liii] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 22

[liv] Ibid. 22

[lv] Ibid. 22

[lvi] Ibid. 26

[lvii] Ibid. 22

[lviii] Ibid. 22-3

[lix] Wordsworth, William. “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour, July 13, 1798.” 34-5 [See also Prologue, note 14]

[lx] Teale, Clara Louise Way. Notes for Edwin Way Teale’s autobiography, Circa 1945-1950. Box 63, folder 2188.

[lxi] Teale, Edwin Way. “Days of Hearsay,” draft, 25-27 July, 1974. The Long Way Home, most complete manuscript. Box 63, folder 2187. 5

[lxii] Teale, Clara Louise Way. Notes for Edwin Way Teale’s autobiography, Circa 1945-1950. Box 63, folder 2188.

[lxiii] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 25-6

[lxiv] Ibid. 26

[lxv] Ibid. 25

[lxvi] Thoreau, Henry David. Walden. Ed. Edwin Way Teale. 9, 7

[lxvii] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 25

[lxviii] Ibid. 25

[lxix] Yeats, William Butler. The Land of Heart’s Desire. Quoted in Dune Boy, Lone Oak Edition, 1957. 11

[lxx] Teale, Edwin Way. Dune Boy. Lone Oak Edition. 11

[lxxi] Teale, Edwin Way. The Trail Wood Journal, 1962-65. 26 May, 1962.

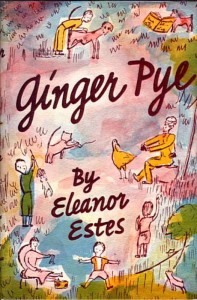

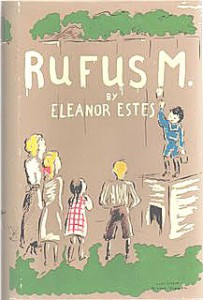

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot.

Eleanor Estes (1906-1988) was one of the most highly acclaimed children’s authors of the mid-twentieth century. I grew up reading her classic stories about the Moffats and the Pyes, and her hauntingly beautiful, iconic tale of childhood bullying, The Hundred Dresses. Born in West Haven, Connecticut, and launching her career as a children’s librarian in the New Haven Free Public Library, Estes reaped three Newbery Honors in three successive years for The Middle Moffat (1942), Rufus M (1943), and The Hundred Dresses (1944) and finally went on to win the John Newbery Medal, awarded for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children, for Ginger Pye (published in 1951), followed by a sequel, Pinky Pye, in 1958. Praised for her microscopically careful observation of the inner life of children, she’s invariably heralded as a leading figure in any discussion of the genre of the “family story.” But she’s also been criticized for what is taken to be her failed attempts, in her later books, to provide more of a sustained and satisfying plot. Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

Thus, John Rowe Townsend complains that, in contrast to the Moffat family stories, “[i]n Ginger Pye . . . there are plots of mystery and detection which call for a dramatic build-up, a logical progression toward climax, which the author is infuriatingly unable or unwilling to provide.” [1] Virginia L. Wolf writes that while Ginger Pye “more effectively focuses on a problem and builds suspense than do any of the Moffat books, [i]t does not, however, as the critics have charged, offer the tightly constructed plot of a successful mystery. . . .” [2]

danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.

danger, and to center her story less on what happens than on children’s quiet and wry observations in response.

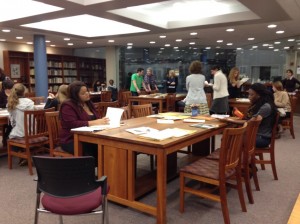

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources.

Introduce your class to primary sources from Archives and Special Collections, UConn’s only public archive that offers students opportunities to explore and experience original letters, diaries, photographs, maps, drawings, artists books, graphic novels, student newspapers, travel narratives, oral histories, and rare sound recordings to illuminate a given topic of study. With over 40,000 linear feet of materials – located in the center of campus at the Dodd Research Center – the Archives welcomes all visitors to its Reading Room, a quiet space to contemplate potentially transformative resources.