This guest blog post is by Gabrielle Westcott, doctoral student in the Department of History at the University of Connecticut. Ms. Westcott received her B.A. in History from Whitman College and her M.A. in History from the University of Connecticut in 2015. Her research examines the influence of emotions and personality on twentieth-century U.S. foreign policy. As a 2016 graduate intern, she spent the summer learning about archival work and exploring the many political collections held at Archives and Special Collections.

In August 1963, after two years of investigation by the U.S. Senate’s Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency and three months before President Kennedy’s assassination, Senator Thomas J. Dodd introduced legislation to amend the Federal Firearms Act of 1938. The bill, S. 1975, addressed the ease with which juveniles and criminals could anonymously purchase mail-order guns and thus circumvent state laws regarding the sale of firearms. As it was first proposed, the bill sought to require individuals who wished to purchase a handgun to submit an affidavit, testifying to their eligibility to purchase a weapon in their home state. The seller would then send a copy of this affidavit to local law enforcement, who would have to authenticate the affidavit before the weapon could be sold. This was later amended so that the seller would simply provide notification of the intended delivery of the firearm to local law enforcement, without having to get police approval of the sale. After the death of President Kennedy, who was shot with a mail-order rifle purchased under a false name, Dodd amended the bill to require an affidavit for both handguns and long guns.

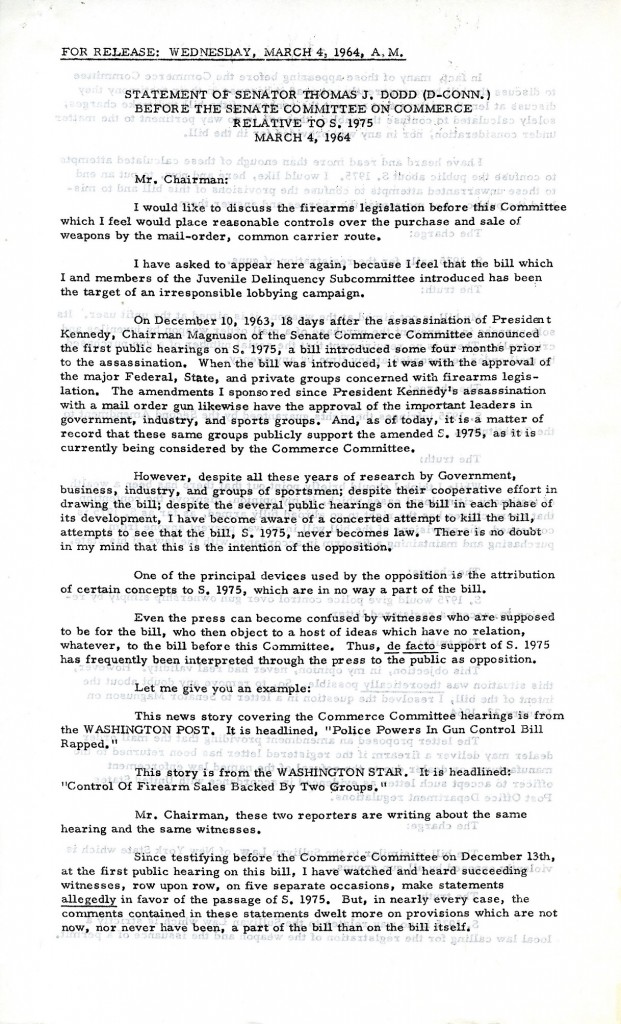

Yet, Kennedy’s assassination inspired criticism of Dodd’s bill on the grounds that it was nothing more than a hysterical reaction to the president’s death. Responding to these claims, Dodd emphasized in speech after speech that the provisions of the bill were the outcome of a two-year investigation, in which the Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency worked with arms manufacturers, arms dealers, law enforcement, sportsmen’s groups, the Department of Justice, and the Treasury Department. Furthermore, the bill had the support of each of these groups, and the executive vice president of the National Rifle Association testified to his organization’s support of the bill on multiple occasions.

Yet, Kennedy’s assassination inspired criticism of Dodd’s bill on the grounds that it was nothing more than a hysterical reaction to the president’s death. Responding to these claims, Dodd emphasized in speech after speech that the provisions of the bill were the outcome of a two-year investigation, in which the Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency worked with arms manufacturers, arms dealers, law enforcement, sportsmen’s groups, the Department of Justice, and the Treasury Department. Furthermore, the bill had the support of each of these groups, and the executive vice president of the National Rifle Association testified to his organization’s support of the bill on multiple occasions.

Despite widespread support, by the end of 1964 the bill was stalled in the Senate Commerce Committee. “What seems to be influencing some members of the Committee to withhold action on this bill,” Dodd noted, “are the protests of people who are either misinformed or bamboozled. In most cases these misinformed protesters have been misled by those who have financial interests in gun running, and by those who have suspect motives which are cloaked under the false cover of anti-Communism, or patriotism, or Constitutional liberties.”[1] Witnesses testifying before the Commerce Committee during the hearings on S.1975 expressed concern that the bill would lead to the registration of firearms. Because sellers would be required to send information about the purchaser’s identity and a description of the weapon to local law enforcement, one witness argued that “whatever regulatory body is chosen to interpret this requirement and draft the applications or forms involved will most assuredly ask for the serial number of the firearm involved. We submit that this is registration.”[2] The Washington Post reported that the National Wildlife Federation and the National Rifle Association opposed the bill’s requirement that the serial number of a gun be reported to law enforcement, while  constituents writing to Dodd and members of the committee expressed concern over the “gun registration provisions” of the bill. Yet there were not, and never had been, gun registration provisions in the bill. Dodd testified to this fact in front of the Committee, noting, “My bill is not aimed at the weapon, it is aimed at the unfit user. . . . There is no requirement that the serial number of a gun purchased by mail order be recorded at any time by any agency.”[3] In the face of such opposition, S. 1975 died in committee. Determined to press on, Dodd reintroduced the bill to the 89th Congress on January 6, 1965 under the title S. 14.

constituents writing to Dodd and members of the committee expressed concern over the “gun registration provisions” of the bill. Yet there were not, and never had been, gun registration provisions in the bill. Dodd testified to this fact in front of the Committee, noting, “My bill is not aimed at the weapon, it is aimed at the unfit user. . . . There is no requirement that the serial number of a gun purchased by mail order be recorded at any time by any agency.”[3] In the face of such opposition, S. 1975 died in committee. Determined to press on, Dodd reintroduced the bill to the 89th Congress on January 6, 1965 under the title S. 14.

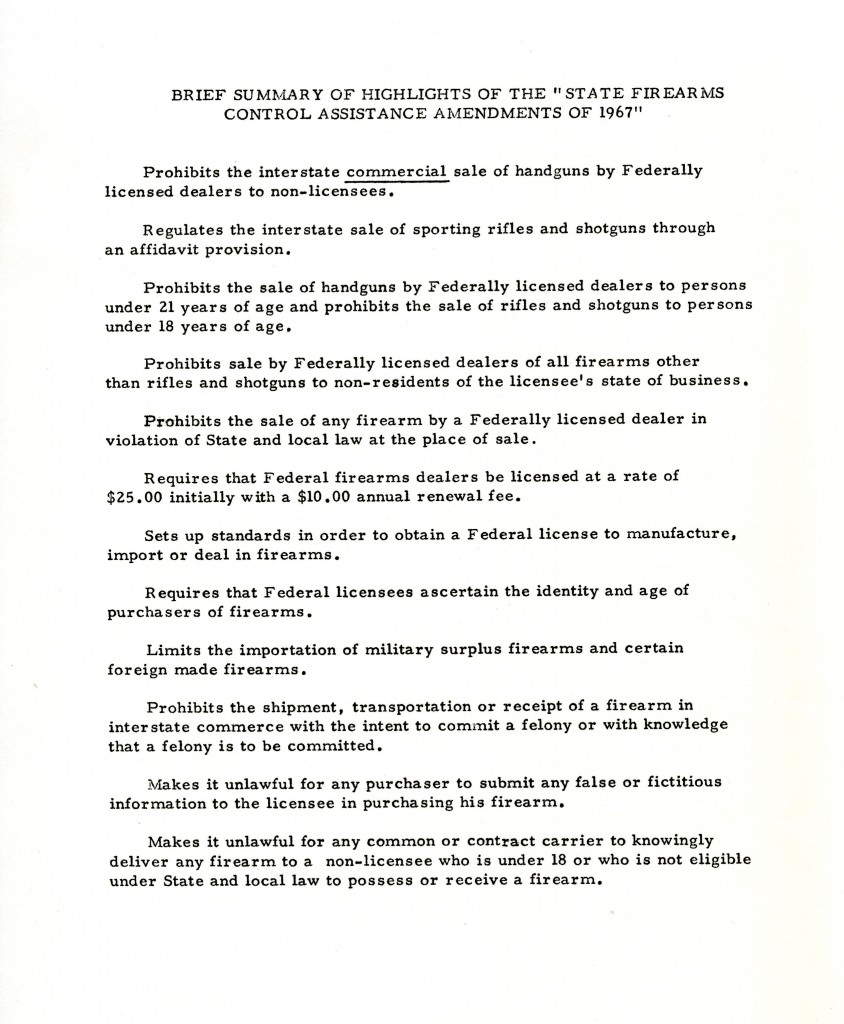

Two months later, on March 8, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson spoke to Congress and proposed a program to wage a war on crime that included controls on mail-order weapons. Seizing the opportunity for a stronger gun control bill provided by the president’s speech, Dodd introduced two bills on behalf of the administration, which Dodd noted, “call[ed] for controls more comprehensive and stringent than I dared to hope for.”[4] The proposed legislation prohibited mail-order sales to individuals, such that persons wishing to purchase a mail-order firearm would have to place their order through a licensed dealer. Furthermore, federally licensed importers, manufacturers, and dealers were prohibited from selling firearms, with the exception of rifles and shotguns, to anyone who was not a resident or businessman of the state in which the seller was located. Finally, federally licensed importers, manufacturers, and dealers were prohibited from selling any type of firearm to an individual under 21 years of age, although rifles and shotguns could be sold to individuals over the age of 18.

It would be three years before Dodd’s legislation prohibiting the interstate mail-order sale of handguns would finally pass in the form of Title IV of President Johnson’s Omnibus Crime Bill. The intervening years would be marked by increasing racial tension, the outbreak of riots in cities across the country, mass shootings, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F.  Kennedy.

Kennedy.

On August 1, 1966, a student at the University of Texas in Austin climbed to the top of the University of Texas Tower and opened fire, leaving 14 people dead and 31 people injured. It was the first mass campus shooting in the United States. The following day, Dodd urged Congress to take action on his firearms legislation, noting, “It is tragic indeed that those of us who call for stronger firearms control laws must rest our case on such headlines as these. How many times will we stand witness to such atrocities before we act? How many more people must die before the American public, the Federal Government and the Congress call in unison for effective firearms legislation?”[5] When two mass shootings occurred in New Haven in that same month, Dodd once again appealed to Congress. “It happened last week. It happened this week. It will happen next week. And it will continue to happen until there are stricter gun laws.”[6] 50 years later, in the wake of Aurora, Sandy Hook, Charleston, Orlando, and countless others, Dodd’s words should haunt us.

While much of the debate surrounding gun control focused on preventing “criminals, drug addicts, mental defectives, and irresponsible juveniles” from purchasing firearms, racial tension undoubtedly played a role in who was deemed fit to own a gun. In 1966, a group in California calling themselves the Black Panther Party for Self Defense began openly carrying firearms to protect African American communities against police brutality. At the time, there was no law prohibiting the open carry of a weapon in a public space. Responding to the actions of the Black Panthers, the California legislature proposed the Mulford Act, which would make it illegal to openly carry loaded weapons. The NRA, it should be noted, supported the legislation. On May 2, 1967, a group of armed Black Panthers entered the chamber of the California State Assembly and interrupted a legislative session to protest the Mulford Act. Speaking to the Senate, Dodd called the incident “a striking example of the need for effective gun control legislation. . . . These armed men serve as a chilling reminder that legislation should be passed swiftly to keep firearms out of such irresponsible hands.”[7] That same month, the NRA encouraged their members to arm themselves to act as “a potential community stabilizer” in the case of urban rioting.[8]

On June 6, 1968, the day after Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated, Johnson signed into law the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act. Title IV of the Act prohibited the interstate mail-order sale of handguns; however, the amendment to prohibit the mail-order sale of rifles and shotguns was defeated. In the wake of Kennedy’s death, and with the support of the Johnson administration, Dodd introduced four new firearms control bills, calling for the inclusion of rifles and shotguns in the Omnibus Crime Control Bill, strict control over the sale of ammunition, the registration of all firearms, and the licensing of all firearms owners. Despite widespread public support for licensing and registration, opponents of gun control managed to remove those provisions from the final legislation. Signed into law on October 22, the Gun Control Act of 1968 was the culmination of five years of legislative effort and seven years of investigation on the part of Senator Dodd and the Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency.

-Gabrielle Westcott, August 2016

[1] “Press Release Concerning Interstate Weapons Traffic,” August 6, 1964, Thomas J. Dodd Papers, Box 200:5080, Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut.

[2] Interstate Shipment of Firearms: Hearings Before the Committee on Commerce, United States Senate, 88th Cong. 194 (1964), ProQuest Congressional Publications (Permalink: http://congressional.proquest.com:80/congressional/docview/t29.d30.hrg-1963-com-0043?accountid=14518) (accessed August 3, 2016).

[3] “Statement of Senator Thomas J. Dodd Before the Senate Committee on Commerce,” March 4, 1964, Thomas J. Dodd Papers, Box 198:5002, Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut.

[4] “Press Release Concerning Amendments to Federal Firearms Act,” March 22, 1965, Thomas J. Dodd Papers, Box 201:5180, Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut.

[5] “Press Release Concerning Need for Stronger Gun Control Legislation,” August 2, 1966, Thomas J. Dodd Papers, Box 204:5363, Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut.

[6] “Press Release Concerning a Shooting in New Haven, CT,” August 26, 1966, Thomas J. Dodd Papers, Box 204:5370, Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut.

[7] “Stronger Gun Laws Needed,” May 31, 1967, Congressional Record, Thomas J. Dodd Papers, Box 207:5550, Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut.

[8] “No Vigilantes, Please,” May 31, 1967, Congressional Record, Thomas J. Dodd Papers, Box 207:5501, Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut.

who happened to keep them.

who happened to keep them.

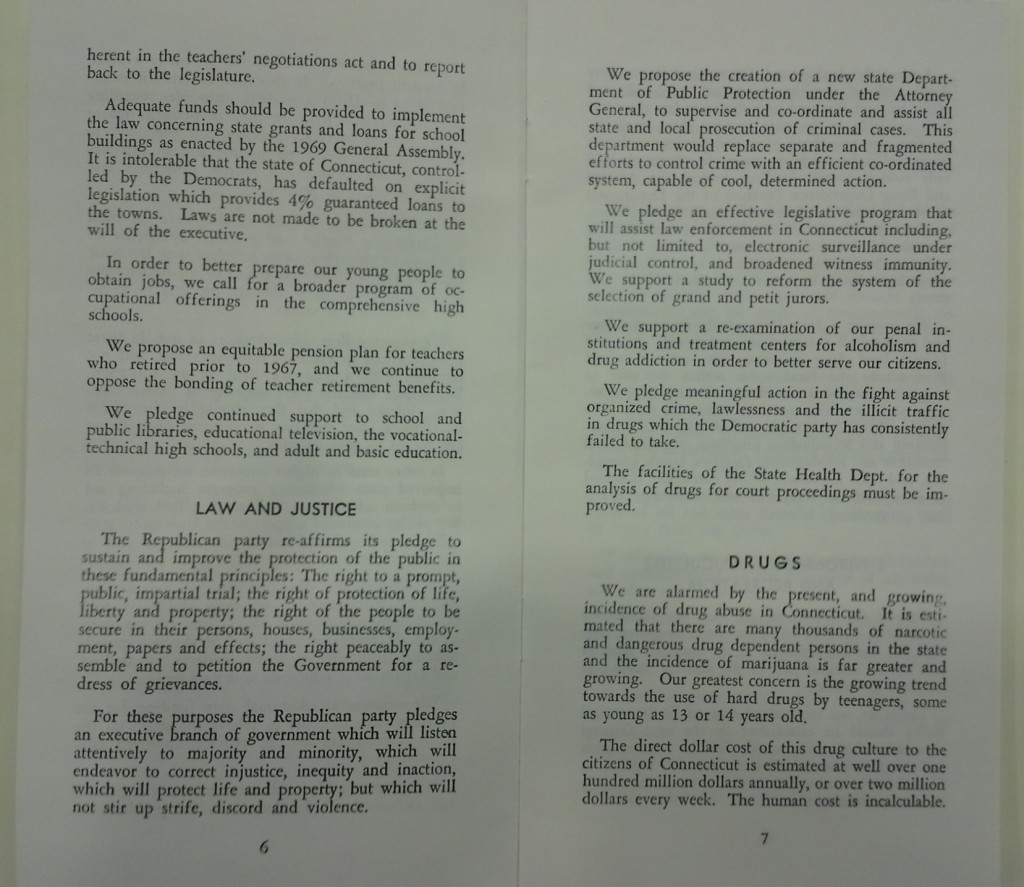

the state parties differ from each other and their national counterparts, and the polarization and nationalization of the two parties. Some might expect these documents – crafted by politicians and political activists – to be stereotypically sparse and platitudinous. However, they tend to run several pages and offer highly specific policy recommendations on a diverse set of issues, including agriculture, criminal law, constitutional rights, transportation, education, and immigration, among many other topics. Therefore, we are hopeful that a systematic hand coding of these documents will allow for a better understanding of America’s two party system and the evolution of policy goals.

the state parties differ from each other and their national counterparts, and the polarization and nationalization of the two parties. Some might expect these documents – crafted by politicians and political activists – to be stereotypically sparse and platitudinous. However, they tend to run several pages and offer highly specific policy recommendations on a diverse set of issues, including agriculture, criminal law, constitutional rights, transportation, education, and immigration, among many other topics. Therefore, we are hopeful that a systematic hand coding of these documents will allow for a better understanding of America’s two party system and the evolution of policy goals.