Written by Shaine Scarminach, a UConn History doctoral candidate, who is currently serving as a Graduate Intern in Archives & Special Collections.

In the mid-1950s, the University of Connecticut led a pioneering studying in the rehabilitation of disabled homemakers. The study sought to examine the challenges faced by orthopedically handicapped women in caring for young children.

Mrs. Mathews of the Handicapped Homemakers Project

Supervised by Elizabeth E. May, Dean of the School of Home Economics, the project received generous funding from the U.S. Office of Vocational Rehabilitation, a part of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. It ran from 1955 to 1960 and included a pilot program of in-home research and a series of academic conferences.

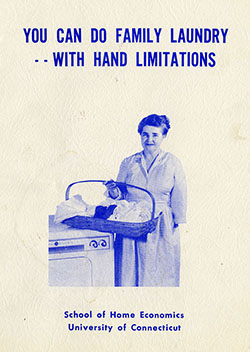

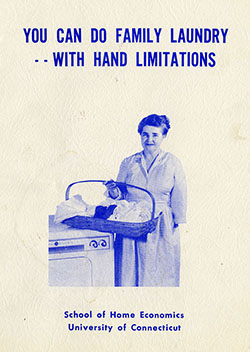

The immediate goal was to produce educational materials for disabled homemakers and their families. But the project had loftier aims as well. Expanding the abilities of disabled homemakers, May thought, could boost individual morale, smooth family relations, and increase the numbers of workers both in and outside of the home.

Mrs. Mathews of the Handicapped Homemakers Project

When organizing the project, May and research coordinator, Neva R. Waggoner, adopted a team approach. The project team comprised a diverse group of researchers – including nurses, therapists, engineers, sociologists, and home economists. Together, they hoped to develop labor saving devices and techniques to help disabled homemakers more easily perform household tasks and increase their overall independence. Collaboration would be key. As May made clear in one report, “This is not an ‘ivory tower’ project!”

The bulk of the study involved holding interviews with disabled homemakers throughout Connecticut. The project team developed a list of interview questions and the n identified around 100 suitable subjects. The women chosen came from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds and lived with various disabilities.

n identified around 100 suitable subjects. The women chosen came from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds and lived with various disabilities.

The team then dispatched a field worker to conduct in-home interviews. This was no small undertaking. Because the interview subjects were scattered around the state and sometimes difficult to locate, the field worker ultimately traveled 8,000 miles over the course of the project.

Mrs. Wilson of the Handicapped Homemakers Project

The interviews were extensive, with questions running to ten pages. Despite the careful research design, the responses left the researchers feeling somewhat discouraged. It became difficult to group the responses into general categories because the subjects experienced their disability in highly individualized ways.

But according to the field worker, the interview subjects cooperated willingly and appreciated the researcher’s interest. The worker even remarked on the “ingenious” ways those interviewed had already adapted their abilities to routine household tasks.

Advertisement for the Handicapped Homemakers Project

After the initial round of interviews, the research team chose to continue working with some women. One case was Mrs. M., “a warm, friendly woman” who had lost an arm to cancer but was eager to return to work. Over a series of visits, a social worker observed Mrs. M. throughout her day and suggested how to adjust her daily tasks or use new equipment as needed. Changes could range from using new cutting sheers or adjustable ironing boards to relearning how to type or drive a car.

The project even had an international dimension. At one point, May took a sabbatical from her teaching and research to explore the European approach to helping disabled homemakers. She traveled across a number of countries in Great Britain, Scandinavia, and elsewhere. At each stop, May lectured about the project underway at UConn and learned about the programs available in the countries she visited. Finland, she found, had made some of the greatest strides in meeting the needs of disabled people in the home.

The project even had an international dimension. At one point, May took a sabbatical from her teaching and research to explore the European approach to helping disabled homemakers. She traveled across a number of countries in Great Britain, Scandinavia, and elsewhere. At each stop, May lectured about the project underway at UConn and learned about the programs available in the countries she visited. Finland, she found, had made some of the greatest strides in meeting the needs of disabled people in the home.

Mr. Ackerman of the Handicapped Homemakers Project

By the time the project ended in 1960, the research team had made significant progress in understanding the needs of disabled homemakers. The final step involved translating the study into

Mrs. Fersch of the Handicapped Homemakers Project conducted by the University of Connecticut in the 1950s

educational materials that included films, slideshows, and pamphlets. May and Waggoner, along with another co-author, also published a book based on the study. Ultimately, the project had achieved its goal of drawing attention to the needs of disabled people working in the home.

For more information about the Handicapped Homemakers Project, see the finding aid to the Elizabeth E. Mays Papers at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/1032 and several hundred photographs from the project at https://collections.ctdigitalarchive.org//islandora/search/%22handicapped%20Homemakers%20Project%22?type=dismax