The following is a guest blog post by Rebecca A.R. Edwards, Professor in the Department of History at Rochester Institute of Technology. Dr. Edwards was recently awarded a Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz Travel Grant to conduct research in Archives and Special Collections. Her research supports a book project tentatively titled Play Ball: Sport, Community, and Memory in Connecticut,” a microhistory that “utilizes local sports history to explore the formation of community identity, social capital, and public memory.”

Sometimes, historical projects get personal. I am a historian at the Rochester Institute of Technology in Rochester, New York. I teach, among other things, the history of baseball and have a long-standing interest in sports history. I could say that my current project is a sports history, and that would be true, but it is also a family history. When I was a girl, growing up in southeastern Connecticut, my paternal grandfather, Danny Rourke, was famous. He played both semi-professional basketball and semi-professional baseball in the state, from 1935-1955. In this way, he was like so many other men in Connecticut in those years, as I have been discovering in the course of my research for a book on this lost sporting world of eastern Connecticut.

We have lost the category of “semi-professional athlete” today. These were men who played organized, competitive sports, largely without long-term professional aspirations. Their basketball was not played to lead to them to the NBA; their baseball was not a road to the MLB. It was an end in itself. Forrest C. ‘Phog’ Allen, the celebrated University of Kansas basketball coach, argued that their play was, in fact, professional. In 1937, he wrote, “The professional—paid or unpaid—plays to win at any cost. Herein lies the significant difference between amateurism and professionalism, whether it be independent or collegiate. When competition becomes a business, it becomes professional. By such interpretation professionalism is not determined by the acceptance of money. The tenor of most independent teams who play outside schedules is professional in spirit, for their stress is on winning and not on the sport for the sport’s sake.”(i) He continued, “The universally accepted definition for a professional player is one who receives compensation for athletic skill or knowledge. If we interpret ‘compensation’ to mean either fame or money or its equivalent, this definition holds.”(ii)

In this way, my work seeks to recover the hidden history of these local professionals. These independent teams that my grandfather played on no longer exist, teams like Pep’s Flashes, the Shymas, and the Danielson Elks. And yet these were teams that attracted hundreds of fans, garnered lots of local press coverage, and brought their players lasting fame. And sometimes, though comparatively rarely, they produced a professional athlete from their ranks.

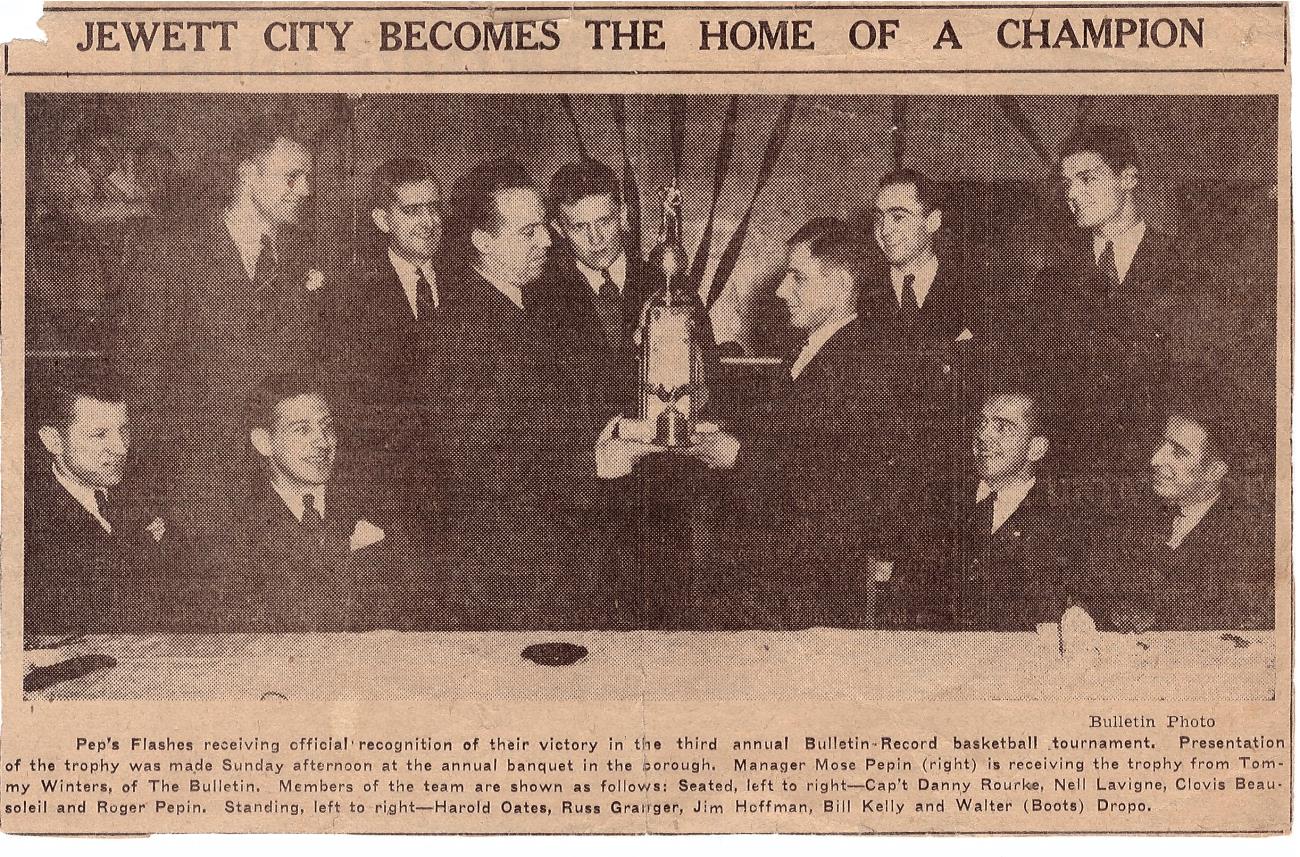

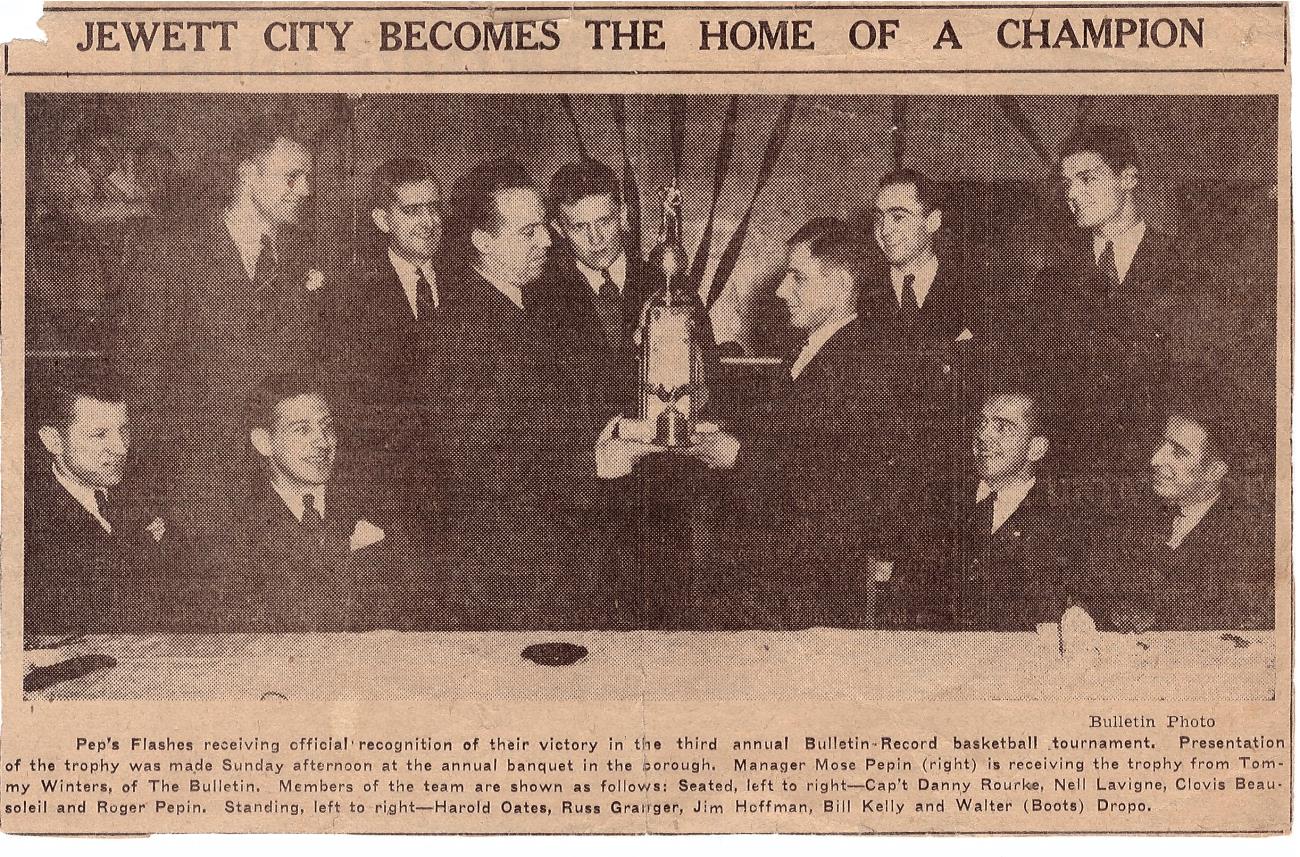

My research brought me into contact with what one might call the pre-history of one of those athletes. He is pictured in the photograph, from the Norwich Bulletin of 31 March 1941, below.  He really is famous. Find him yet? He is a very young Walt Dropo, then in his senior year of high school. He is in the back row, all the way to the right. Dropo was the youngest member of Pep’s Flashes, pictured here after winning the Norwich Bulletin-Record basketball tournament.

He really is famous. Find him yet? He is a very young Walt Dropo, then in his senior year of high school. He is in the back row, all the way to the right. Dropo was the youngest member of Pep’s Flashes, pictured here after winning the Norwich Bulletin-Record basketball tournament.

The captain of the team was my grandfather, seated at the far left. The Sunday sports page announced the news of their victory. “Pep’s Flashes Win Bulletin-Record Tournament, 48-37; Jimmy Hoffman and Danny Rourke Are the Stars.” The game was played before a “packed house of about 450 noisy customers…making it the third night that the games were played before a capacity audience.” Pep’s led the entire way, and though the “game was never close enough to get the fans steamed up…it was bruising, tough basketball from start to finish and nobody was disappointed.” The Norwich Record praised the team, saying, “Pep’s really looked the part of champions. Their passing and their shooting was a beautiful thing to watch and were altogether too classy” for their opponents, the Doco Eagles of Norwich. Hoffman was the game’s high scorer, while Rourke played “a marvelous floor game.” They had help from ‘Boots’ Dropo, who contributed nine points.(iii)

‘Boots’ Dropo, as he was then known, would go on from Plainfield High School to attend the University of Connecticut, as probably everyone already knows. Upon Dropo’s death in 2010, Coach Dee Rowe called him “the greatest all-around athlete this school has ever seen.” Dropo played football, basketball, and baseball for the Huskies. He was drafted by the Chicago Bears in the 9th round of the 1946 NFL draft. He was drafted in the first round of the 1947 BAA (Basketball Association of America, a pro-league pre-NBA) draft by the Providence Steamrollers. But he turned it all down to sign with the Red Sox organization in 1947.

In 1950, Walt Dropo was the American League Rookie of the Year, the first Red Sox to be named Rookie of the Year. He finished sixth in the AL MVP race. His .583 slugging percentage that year was second only to Joe DiMaggio (.585). “New England was full of Walt Dropos then,” Bill Reynolds writes, “small town kids who stole the hearts of their communities because of the way they played this New Game.”(iv) But that was still ahead of him. As late as 1946, you could have seen Walt Dropo playing basketball in a 200 seat auditorium in southeastern Connecticut with my grandfather.

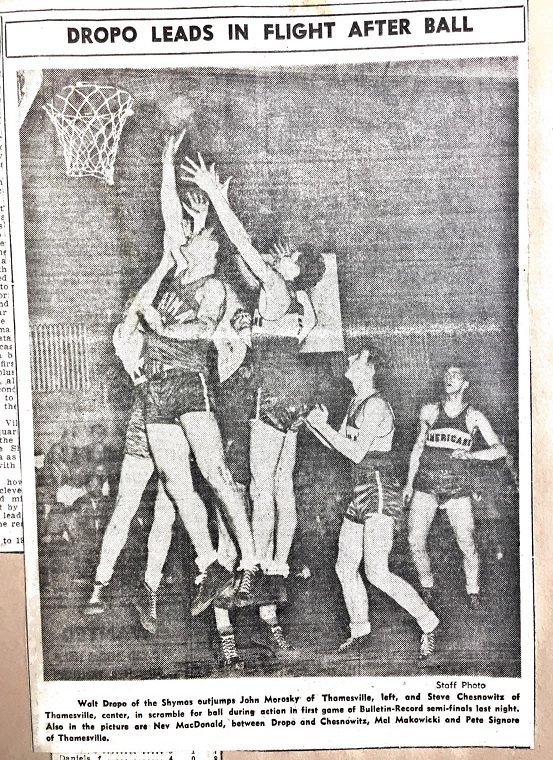

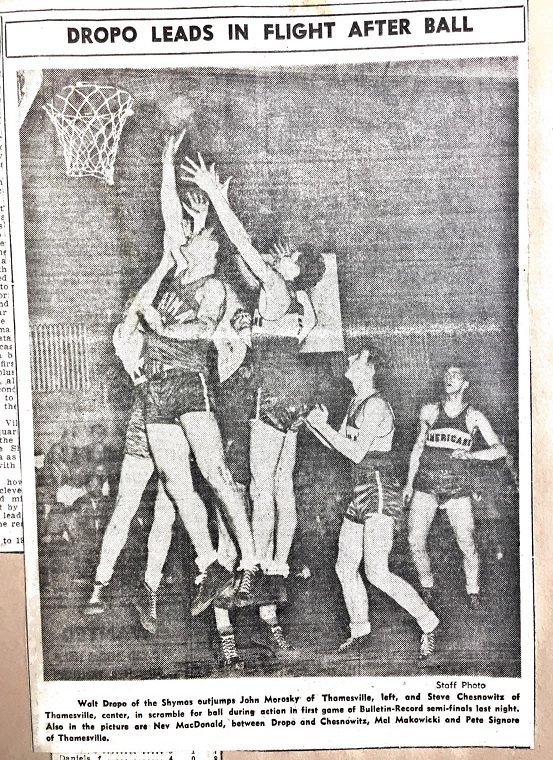

By then they were both playing for the Shymas, who would also win the Norwich Bulletin-Record title. Dropo is seen here, in the semi-finals of the tournament.

The press coverage noted that Dropo and Rourke were key members of the team. “The Shyma club five of Taftville steamrolled to a 65 to 49 victory over the Windham Packards of Willimantic at the Norton Gym Saturday night to win the eighth annual Norwich Bulletin-Record basketball tournament before a capacity crowd of better than 600 fans….The Packards held the lead twice in the opening minutes of play, 2 to 0 and 4 to 2, but after that point they didn’t stand a chance as the Villagers swept down the floor time and again using the height of MacDonald and Walt Dropo and the floor work of Bill Kelly and Danny Rourke to great advantage. Besides giving a brilliant offensive exhibition throughout the contest, the Shyma put up a tight defense that the Willimantic combination had plenty of trouble cracking.”v Another account concluded that, in winning the tournament, the Shyma had demonstrated that they were “the outstanding hoop combination in eastern Connecticut during the past year.”(vi)

Dropo left for the Red Sox farm system the following year, in 1947. But he left having already played for two different championship basketball teams in Connecticut. As we remember his sports history today, we largely assume it starts with the Red Sox. His time in college sports is seen as a prelude to his professional career. My work allows me to see that he brought a champion’s play to UConn with him. He had been playing alongside semi-pro athletes since he was in high school. That was the drive he brought with him to Storrs.

The distance between the professional world of sports that Dropo would enter and the semi-professional levels of sport he was leaving behind was not very wide. Professionals were a part of their local communities then and semi-professionals were treated with much the same reverence and respect. October 14, 1950, was Walt Dropo Day in his hometown of Moosup, Connecticut. Dropo came into town with a barnstorming baseball team, the Birdie Tebbett’s All-Stars. George ‘Birdie’ Tebbett’s was a catcher with the Red Sox. Also barnstorming with Tebbett’s team that fall were Phil Rizzuto and Johnny Pesky.

They faced a home team, put together for the occasion, called the Connecticut All-Stars. Walt’s brother, Milt Dropo, himself a star athlete at the University of Connecticut, managed the All-Stars. Playing for them in right field was Danny Rourke. He was at that point playing for the New London Raiders in the Class B Colonial League, an effort to revive minor league baseball in southern New England. The original Colonial League had folded in 1915. This Colonial League was formed for the 1947 season; its last season was 1950. Walt Dropo Day was the last time that Dropo and Rourke took a field together.

Dropo’s career brought him to the MLB. Rourke’s career ended in Class B. Yet, the two men shared an athletic journey together that dated back to 1941. My grandfather is still remembered in some circles in southeastern Connecticut today, where I still sometimes meet old fans who call me “Danny Rourke’s granddaughter.” So I know sporting memories can be long. I had wondered, as I came to the Archives to search for images of Dropo’s college career, how well he was remembered on campus today. I worried a bit as the young archivist, whose name will remain unmentioned to protect the guilty, admitted that he had never heard of him until I started asking for files to be pulled. (He was brave to admit that to me and he was otherwise a perfectly nice professional, just to be clear.)

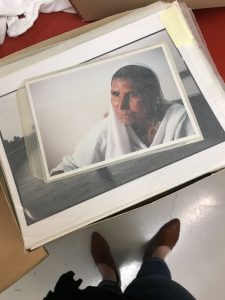

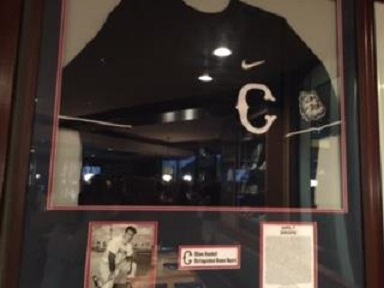

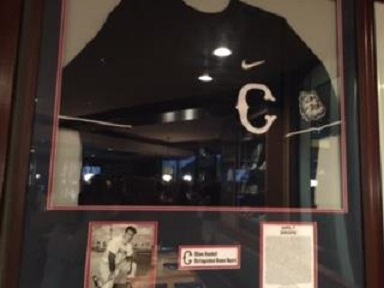

I was worried for nothing. As I settled into the Nathan Hale Hotel, I stopped at their pub for a beer, after a long day in the archives. I glanced over my head and found that I had taken a seat under Walt Dropo.

I was worried for nothing. As I settled into the Nathan Hale Hotel, I stopped at their pub for a beer, after a long day in the archives. I glanced over my head and found that I had taken a seat under Walt Dropo.

‘Boots’ Dropo. Still here, after all these years.

– Rebecca A.R. Edwards

Notes:

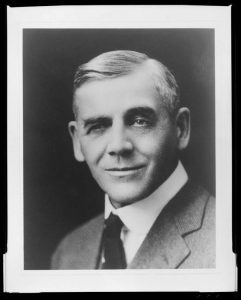

i Forrest C. Allen, Better Basketball: Technique, Tactics, and Tales (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1937), 7. ‘Phog’ Allen coached at Kansas from 1919-1956. He coached the Jayhawks to victory in the NCAA tourney in 1952, the same year that he coached the Olympic basketball team to a gold medal at the Helsinki games. He was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1959.

ii Allen, 8.

iii All coverage from “Third Annual Bulletin Record Tourney.” Undated clipping. Potts family scrapbook.

iv Reynolds, Our Game, 7.

v “Shymas Take Bulletin-Record Tourney With 65-49 Win,” Norwich Record (March 31, 1946), 13. From Rourke family scrapbook.

vi “Bulletin Record Tournament Won By Shyma Club.” Undated press clipping. Rourke family scrapbook.