This post was written by Shaine Scarminach, a UConn History Ph.D candidate who is a student assistant in Archives & Special Collections.

The students filed into the building, one after the other. They made their way to the east wing, where they fanned out among the tables and chairs. Some pulled pen and paper from bags, others opened books carried under arms. “Right on, this gives me a chance to tighten up on my studyin’,” someone said. Most stayed silent.

For the staff on duty, nothing seemed amiss. It was April 22, 1974, an ordinary day at the Wilbur Cross Library on the University of Connecticut campus. Masses of students moved in and out of the building, and the staff served them as usual. The trouble came at closing time.

Just before midnight, an employee asked the 200 or so black students gathered in the library to leave. The students stayed put. They had come to study—in part.

But they had also come to protest.

The early 1970s were a turbulent time for the University of Connecticut. The social awakenings of the 1960s had taken their toll on the university and its beloved president, Homer D. Babbidge.

Toward the end of his term, Babbidge had to contend with a series of high-profile protests against the U.S. war in Vietnam.

In 1967-68, demonstrators led by the local chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) disrupted on-campus interviews held by recruiters for Dow Chemical Company and the Olin-Mathieson Corporation. At the time, both companies produced munitions and chemical weapons for the U.S. government.

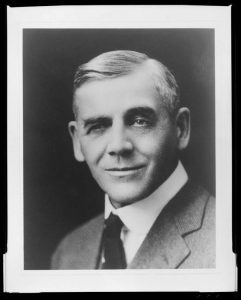

UConn President Homer Babbidge in “Diary of a Student Revolution,” 1969.

During the demonstration against Olin-Mathieson in November 1968, President Babbidge sent in 200 local police to disperse crowds and arrest protesting students and faculty. These events were later chronicled in a television documentary, Diary of a Student Revolution.

In 1970, Babbidge faced continued actions on the part of SDS and other student groups. During the spring semester, students continued to protest the U.S. involvement in Vietnam with an occupation of the ROTC hangar and a general strike against the war. In need of a respite, President Babbidge retired from his position in early 1972.

After a long and torturous search for a replacement, Glenn W. Ferguson became university president in May 1973. His tenure would at times be just as rocky as his predecessor’s.

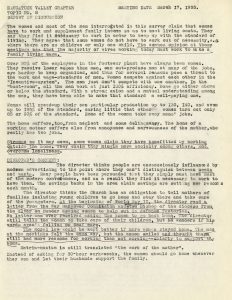

Demands made by UConn’s Black Students, April 22, 1974.

Ferguson faced a tangle of difficult issues from his first day in office: the coming of collective bargaining for faculty and staff, discontent over the campus bookstore, upheavals in the Anthropology Department, and the rising demands of women and minority students.

The latter concern pushed the group of black students to occupy the library. It also brought them into sharp conflict with their new president.

On April 11, a few weeks before the library sit-in, 300 black students marched to Gulley Hall, home of the university president’s office, to deliver Ferguson a list of demands.

Among other things, the students demanded that the university reunite the recently divided Anthropology Department; conduct an investigation into two professors the students accused of producing racist research; support the construction of an Afro-American Cultural Center; and provide greater recruitment and support for black and other minority students.

President Ferguson responded to the list of demands in a letter to Rodney Bass, Chairman of the Organization of Afro-American Students, on April 16, 1974, five days after the initial protest.

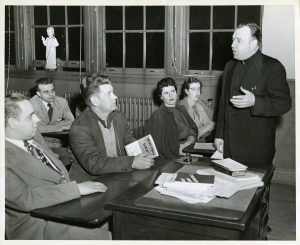

Local police enter Wilbur Cross Library to remove protesters, April 23, 1974.

Ferguson wrote that “the demands are timely, well-presented, and deserve a definitive answer.” After an introductory note, he spent three pages answering each point in detail. He finished the letter by thanking Bass for bringing the issues to his attention and affirming that the University of Connecticut had an obligation to support its minority students.

Yet the coalition of black students deemed the president’s response anodyne and evasive.

In a reply delivered to Ferguson the following day, the students characterized his letter as “middle of the road.” It signified what the students had come to expect from administrators on campus—“vague and ambiguous procrastination.”

Absent any real commitment from the president, the students felt compelled to take their message beyond the confines of Gulley Hall. Ferguson’s lackluster response had pushed the students to further protest.

Studying together in the library after hours on the night of April 22-23, the coalition of black students sought to increase the pressure on administrators to meet their demands.

Not long after the sit-in began, campus police and other university officials gathered outside the building. Someone informed the students that the library was closed and they would have to leave.

The students refused, instead reading a prepared statement. They planned to occupy the library until President Ferguson and other administrators met with them at 6:00 am to discuss their demands. If the administrators failed to show up, the students would remain in the library until they did.

[slideshow_deploy id=’7925′]

A tense stand-off ensued. Around 3:00 am, the students received a notice from Ferguson instructing them to leave in fifteen minutes or be in violation of university regulations and state laws. If they stayed, they would be subject to sanction and arrest. The students held firm, leaving the university administrators struggling to find a solution.

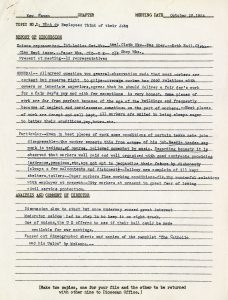

By 6:00 am, it had become clear that the students had no intentions of leaving the library, and President Ferguson and the other administrators had no intentions of meeting with them. By that time, around forty-five police officers had also amassed outside the library. After about an hour, the administration sent in the police to forcibly remove the students.

Police officers, sometimes four at a time, pulled and dragged the protesting students out of the library and then packed them onto waiting buses. They were brought to police stations in Mansfield and Stafford Springs, where they were charged with criminal trespassing and other offenses.

The protesting students reported being physically and verbally abused by police. One student was even admitted to the infirmary because of his injuries.

Ferguson’s decision to call in the police provoked an immediate uproar on campus and throughout the state. Praise and condemnation for both the students and Ferguson came from many quarters.

A number of individuals and groups offered their support for the students.

An editorial in Contact, the newspaper produced by the Afro-American Cultural Center on campus, described Ferguson’s decision to send in the police “an act of monumental stupidity and arrogance.” A student group at Trinity College went further, calling it “savage racism.” A letter from the parents of one UConn student wondered if Ferguson had considered how his “rash and callous action” would hurt the students’ future prospects.

[slideshow_deploy id=’7961′]

Most notably, a group of about seventy mostly white students and a few faculty members held an identical protest in the library the following evening. The solidarity protest was again broken up by university staff and local police.

Ferguson also received his fair share of support. One letter sent to the president’s office praised the “hard line” he had taken against the students. Another letter commended his “prompt and decisive action.”

Contact, a UConn Student Publication, May 1974

Although some of the supporting letters acknowledged that the students had a legitimate grievance, some reflected condescension or outright racism. One letter writer not only praised Ferguson’s decision to call in the police but offered his own assessment on the issue of an Afro-American Cultural Center: “I have been to Africa, and if what I saw there represents black culture, I think the world is just as well off without it.”

After intervention by local chapters of the ACLU and NAACP, among others, the president’s office helped get a nolle verdict for the arrested students. Instead, they faced internal discipline from the dean’s office.

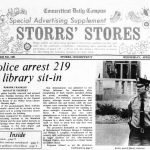

April 24, 1974, issue of the Connecticut Daily Campus

The library sit-ins illustrate the dramatic changes underway at the University of Connecticut in the early 1970s. On the Storrs campus, students and staff strained under many of the same pressures felt throughout the United States at this time.

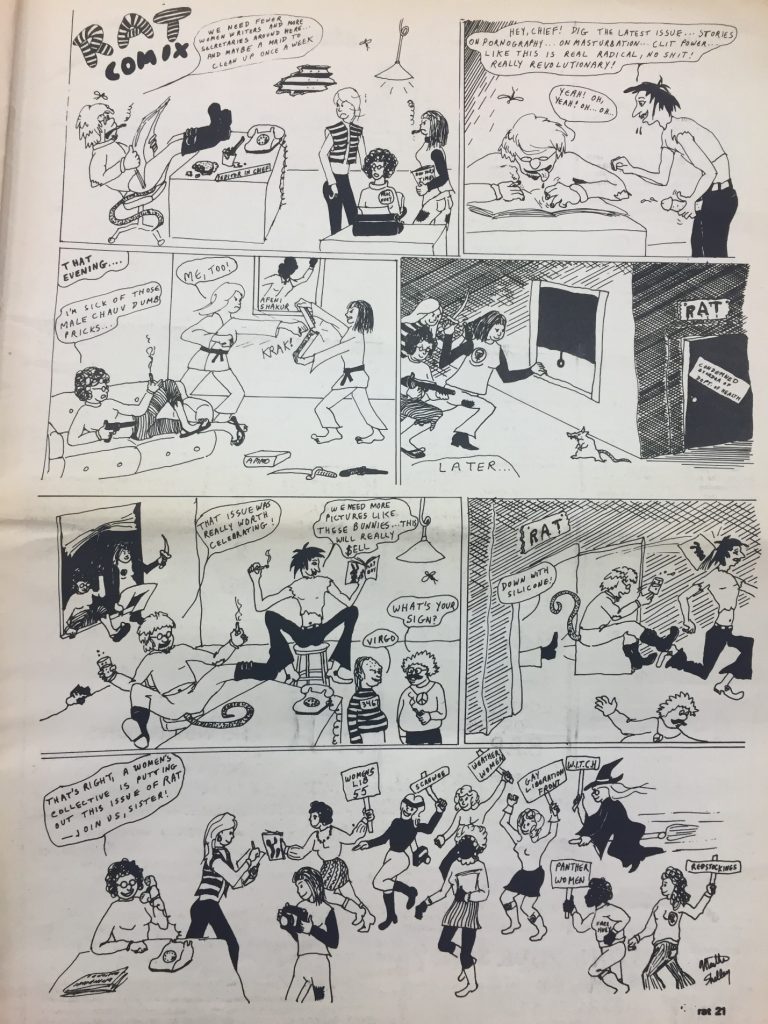

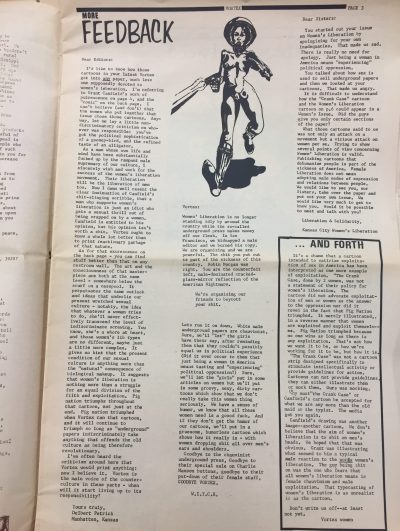

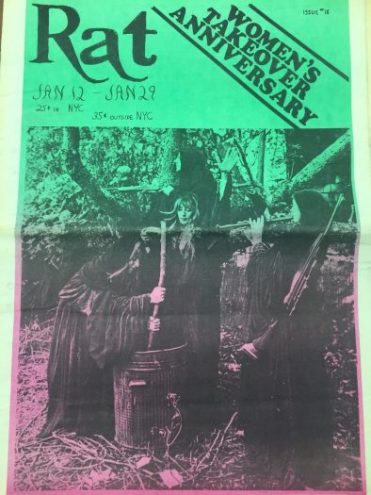

The letters in support of Ferguson’s actions signaled a growing backlash against radical protest, while the students’ actions highlighted the increased militancy of the movements for black and women’s liberation. The university, in short, had become one battleground in a wider conflict threatening to tear the nation asunder.

Many more photographs of this event are available in our digital repository, at http://archives.lib.uconn.edu/islandora/search/black%20student%20protests%20in%20Wilbur%20Cross%20Library?type=dismax