In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a flower struck by Cupid’s bow is instantly imbued with magical powers. A touch of the nectar from the flower, a wild pansy, to the eye of the sleeping fairy queen Titania causes her infatuation with Bottom and the ensuing chaos that follows in the play. Plants, flowers and herbs figure prominently in several of Shakespeare’s plays, most notably A Midsummer Night’s Dream and A Winter’s Tale. During Shakespeare’s time, the wild pansy was known by many names including “Heartsease,” “Love-lies-bleeding,” and “Jack-jump-up-and-kiss-me”. Botanicals in medieval Europe have long cultural histories and symbolic meanings derived from their use as curatives and medicine through time. When characters such as Oberon and Puck from A Midsummer Night’s Dream mention flowers and herbs, it can be assumed that Shakespeare drew from these deep histories and intended for the audience to understand the associations that each flower represented.

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a flower struck by Cupid’s bow is instantly imbued with magical powers. A touch of the nectar from the flower, a wild pansy, to the eye of the sleeping fairy queen Titania causes her infatuation with Bottom and the ensuing chaos that follows in the play. Plants, flowers and herbs figure prominently in several of Shakespeare’s plays, most notably A Midsummer Night’s Dream and A Winter’s Tale. During Shakespeare’s time, the wild pansy was known by many names including “Heartsease,” “Love-lies-bleeding,” and “Jack-jump-up-and-kiss-me”. Botanicals in medieval Europe have long cultural histories and symbolic meanings derived from their use as curatives and medicine through time. When characters such as Oberon and Puck from A Midsummer Night’s Dream mention flowers and herbs, it can be assumed that Shakespeare drew from these deep histories and intended for the audience to understand the associations that each flower represented.

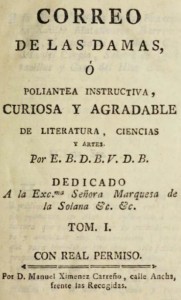

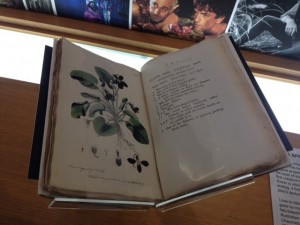

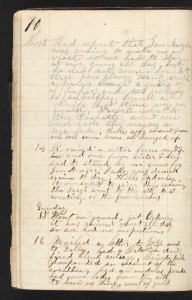

A rare text on the medicinal properties of plants and other botanicals from the collections of Archives and Special Collections is currently on display in the exhibition The Plays the Thing: Shakespeare at UConn in the Homer Babbidge Library plaza level gallery. Flore Medicale [Medicinal Plants] is a catalog of plants and hand painted illustrations produced by Francois-Pierre Chaumeton, a French botanist, physician, surgeon, and eventual  pharmacist. He lived from 1775 to 1819 and practiced for most of his professional life at the Val-de-Grace military hospital in Paris. Chaumeton translated medicinal texts from Latin, Italian, French and other languages and compiled the 8 volume Flore Medicale. The set was first published in 1814 and contains over 360 hand-painted illustrations of plants in total.

pharmacist. He lived from 1775 to 1819 and practiced for most of his professional life at the Val-de-Grace military hospital in Paris. Chaumeton translated medicinal texts from Latin, Italian, French and other languages and compiled the 8 volume Flore Medicale. The set was first published in 1814 and contains over 360 hand-painted illustrations of plants in total.

The exhibition features commentary from several UConn faculty members on different facets of Shakespearean scholarship. Associate Professor F. Elizabeth Hart discussed Shakespeare’s allusions to Queen Elizabeth I in plays such as Comedy of Errors, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and The Winter’s Tale; Professor Pamela Allen Brown provides examples of “The Advent of the Actress and Shakespeare’s All-Male Stage”; and Professor Gregory Semenza provided samples of Shakespearean influence in modern culture in the form of comic strips, graphic novels, and video games.

Though the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death will be recognized in 2016, it is unlikely that students and scholars will ever come to a complete understanding of William Shakespeare and the influence that his work has had on the English language. In The Play’s the Thing: Shakespeare at UConn, Connecticut Repertory Theatre’s (CRT) Managing Director Matthew Pugliese and Assistant Professor in the Department of Dramatic Arts Lindsay Cummings show the creative work of the students and artists of the Department of Dramatic Arts and Connecticut Repertory Theatre. The exhibition is on display until June 15, 2015.

Though the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death will be recognized in 2016, it is unlikely that students and scholars will ever come to a complete understanding of William Shakespeare and the influence that his work has had on the English language. In The Play’s the Thing: Shakespeare at UConn, Connecticut Repertory Theatre’s (CRT) Managing Director Matthew Pugliese and Assistant Professor in the Department of Dramatic Arts Lindsay Cummings show the creative work of the students and artists of the Department of Dramatic Arts and Connecticut Repertory Theatre. The exhibition is on display until June 15, 2015.

– Lauren Silverio

Lauren Silverio is an English and Psychology major and student employee in Archives and Special Collections.

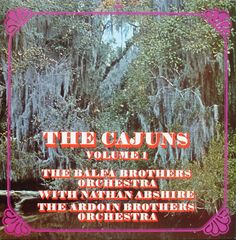

washboard, banjo and clarinet player, Korean war veteran, art collector, jazz musician and literary scholar. And I’ve probably left some things out. He was also tireless.

washboard, banjo and clarinet player, Korean war veteran, art collector, jazz musician and literary scholar. And I’ve probably left some things out. He was also tireless.