[slideshow_deploy id=’8546′]

In 1893, after an act of the Connecticut General Assembly, the rustic Storrs Agricultural School was remade into Storrs Agricultural College, a first step on its way to becoming the major research university we know today as the University of Connecticut.

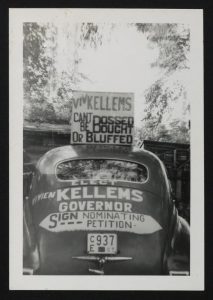

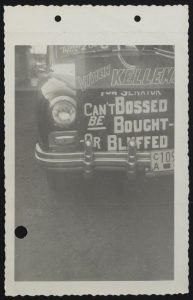

Along with a new name, the college expanded its course offerings, hired new faculty, and admitted new students—most notably, it officially opened its doors to women. Some members of the General Assembly initially tried to bar women from attending, only to be defeated in the end. Even so, it would have been a belated effort. Records indicate that by 1893 about twenty women had already taken classes at the school, either because of the forward-thinking president Benjamin F. Koons or simply because no law existed to discourage them.

Either way, women’s presence at UConn continued to expand in subsequent years. More and more female students attended classes, played on sports teams, and engaged in student activities in and around the campus, while female faculty and staff assumed a greater number of academic and administrative positions. Today, women account for a slight majority of students at UConn, and the evolution from that first twenty students to women’s prominent role on campus today is amply documented by the university archives.

Archives & Special Collections holds a wealth of materials for those interested in exploring the integral role of women at UConn. Among the relevant collections are:

- President’s Office Records. The collection comprises extensive material relating to each presidential administration at UConn. The records from Glenn W. Ferguson’s presidency (1973-1978) are especially relevant. They contain significant material on attempts to include women’s concerns in the university’s affirmative action plan, and the controversy and activism around the denial of tenure to English professor Marcia Lieberman. The finding aid can be found at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/606

- UConn Women’s Center Records. The collection comprises books, correspondence, notes, fliers, clippings, publications, legal records, and transcripts relating to the University of Connecticut’s Women’s Center from 1970 to 1989. The UConn Women’s Center was founded in 1972 after concerted student activism and continues to exist today. It provides a range of social services, educational opportunities, and community outreach at the University of Connecticut around a host of issues relating to women and beyond. The finding aid can be found at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/187

- UConn Women’s Studies Program Records. The collection comprises grant files, administrative records, announcement, fliers, and publications. The University of Connecticut’s Women’s Studies Program began in 1974 and was the first official program for women’s studies in Connecticut. Similar to UConn’s Women Center, the Women’s Studies Program formed after concerted efforts by students, faculty, and staff to include women’s interests and issues on campus, especially amid a renewed wave of feminist organizing in the 1960s and 1970s. The finding aid can be found at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/754

- One Hundred Years of Women at UConn Collection. The collection comprises the contents of a scrapbook created to document the 100 Years of Women activities at UConn during the 1991-1992 academic year. The scrapbook contained photographs, clippings, programs, announcements, memoranda, correspondence, flyers, brochures and posters. The scrapbook was created by a committee formed by President Harry J. Hartley in 1991, and then led by Professor Cynthia Adams, to develop a year-long program of activities to celebrate the role of women in UConn’s history. The activities included a convocation, lectures, presentations, awards and an exhibition. The finding aid can be found at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/580

- Athletic Communications Office Records. The collection comprises materials concerning the full range of UConn athletics, including basketball, softball, field hockey, tennis, swimming, and many other sports. Records for individual sports contain publications, media guides, statistics, correspondence, press releases, newspaper clippings, and other materials, many over long periods of time. The collection also holds a significant archive of press releases and other general materials. Overall, the collection represents some of the most extensive coverage of UConn athletics and provides a detailed portrait of women in sports at UConn. The finding aid can be found at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/796

- Student Newspapers. The collection comprises digitized issues of student newspapers from multiple UConn campuses. The most significant collection comes from the Storrs campus, including extensive runs of early to contemporary student newspapers like the Lookout and the Daily Campus. These newspapers provide some of the most far-reaching and wide-ranging coverage of student life at UConn. Both the student newspapers and the student yearbook supply a useful means to chart the history of women at UConn. Many of the publications can be found in our digital repository at http://hdl.handle.net/11134/islandora:campusnewspapers

- Nutmeg. The collection comprises digitized copies of UConn’s student yearbook from 1915 to 2008. Similar to the student newspapers, the student yearbook provides a useful means of understanding the evolving place of women at UConn. The yearbooks contain information on individual students, clubs, sports, campus activities, academics, and information on particular academic years. The yearbooks furnish an especially useful means to survey the expanding presence of women at UConn, both in terms of faculty and students. Issues of Nutmeg from 1915 to 1999 can be found in our digital repository at http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:02653871

- University of Connecticut Photograph Collection. The collection comprises digitized photographs from throughout UConn’s history. The extensive collection of photographs documents women in all aspects of university life, from sports and academics to university clubs and social life. The finding aid can be found at http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:MSS19880010

We invite you to view these collections in the reading room at Archives & Special Collections. Our staff is happy to assist you in accessing these and other collections in the archives.

This post was written by Shaine Scarminach, a UConn History Ph.D candidate who is a student assistant in Archives & Special Collections.