The UConn Archives & Special Collections podcast d’Archive will release it’s 50th episode on April 24th, 2023 with a live broadcast at 10am EST on 91.7fm WHUS. Beginning in August of 2017, the Archives staff began expanding its outreach program to the airwaves by training on sound engineering and radio protocols in order to effectively bring its collections to new audiences. Since then the radio program and podcast has featured weekly episodes drawing from countless collections held by the Archives & Special Collections and amplifying the expertise of over 60 collaborators ranging from past and present archives and library staff, artists, journalists, curators, faculty, graduate and undergraduate students, high school students, visiting fellows and international students, activists, alumni, collectors and donors, family, and friends.

Continue readingCategory Archives: From the Researcher’s Perspective…

James Marshall the Educator: Audio Cassette Lectures at UConn, 1976-1990

The following guest post is by K-Fai Steele, recipient of the 2019 James Marshall Fellowship. K-Fai (www.k-faisteele.com) is an author and illustrator who grew up in a house built in the 1700s with a printing press her father bought from a magician. She wrote and illustrated A Normal Pig. She illustrated Noodlephant by Jacob Kramer (a Kirkus Best of 2019 picture book) and Old MacDonald Had a Baby by Emily Snape. She also illustrated the forthcoming Probably a Unicorn by Jory John and Okapi Tale, the sequel to Noodlephant. She was a Brown Handler Writer in Residence at the San Francisco Public Library, and the 2018 Ezra Jack Keats/Kerlan Memorial Fellow at the University of Minnesota. K-Fai lives in San Francisco.

The job of a professional children’s book author and illustrator is challenging. There’s no one formula for, or definition of success. The job walks the line between commercial and creative disciplines and requires a bizarre combination of skills: not only writing and illustrating books but being able to perform in front of large varied audiences (toddlers one day, fifth graders the next), deftness at publicity and social media, teaching, and generally being able to project an aura of success and expertise. It can often feel competitive and lonely. And one is paid as a freelancer, so (at least in the United States) there is no economic safety net and it’s hard to plan for a long term career. Another aspect of the job requires constant learning, growth, and improvisation which can either be stressful or exciting and luxurious (if you have the time and space to fully devote to it). Whenever I feel stuck I end up in a library and I’ve learned that some of the best libraries and collections contain public collections of children’s literature preliminary materials. The University of Connecticut is one of these places, and through the James Marshall Fellowship I was given the time, space, and funding to spend time learning and luxuriating in their collection.

If you spend enough time with someone’s work you get a sense of their process; in a way it’s the closest thing you can get to a mentorship. In his essays Caldecott & Co.: Notes on Books and Pictures, Maurice Sendak quotes Alphonse Mucha (a mentor to one of Sendak’s heroes Winsor McKay, the creator of the Little Nemo comic): “I think it would be wise for every art student to set up a certain popular artist whom he likes best and adapt his ‘handling’ or style… when you are puzzled with any part of your work, see how it has been handled by your favorite and fix it up in a similar manner.” It’s a very clever way to get a very good (and free) education.

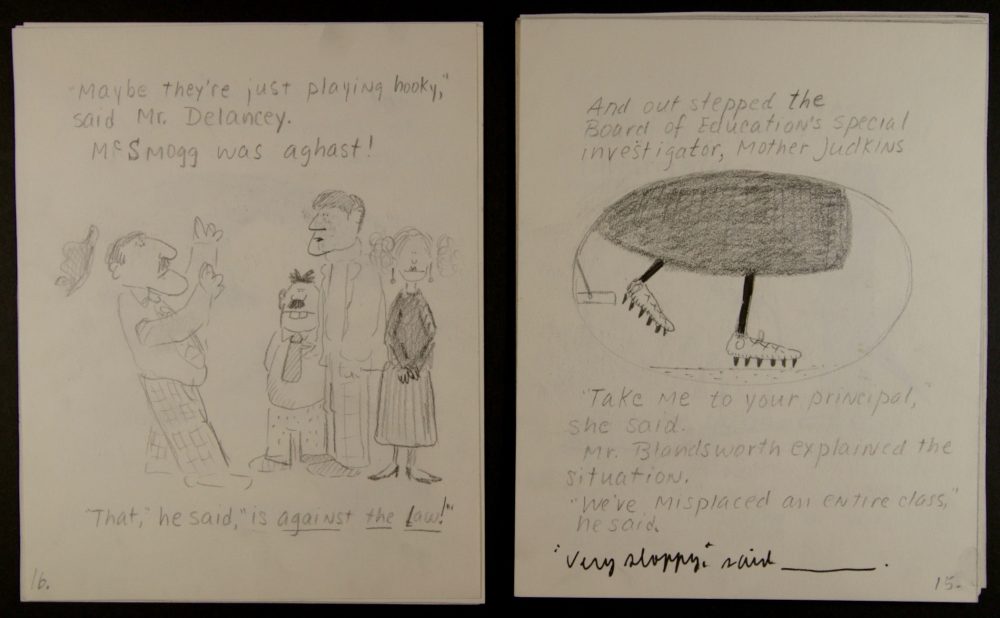

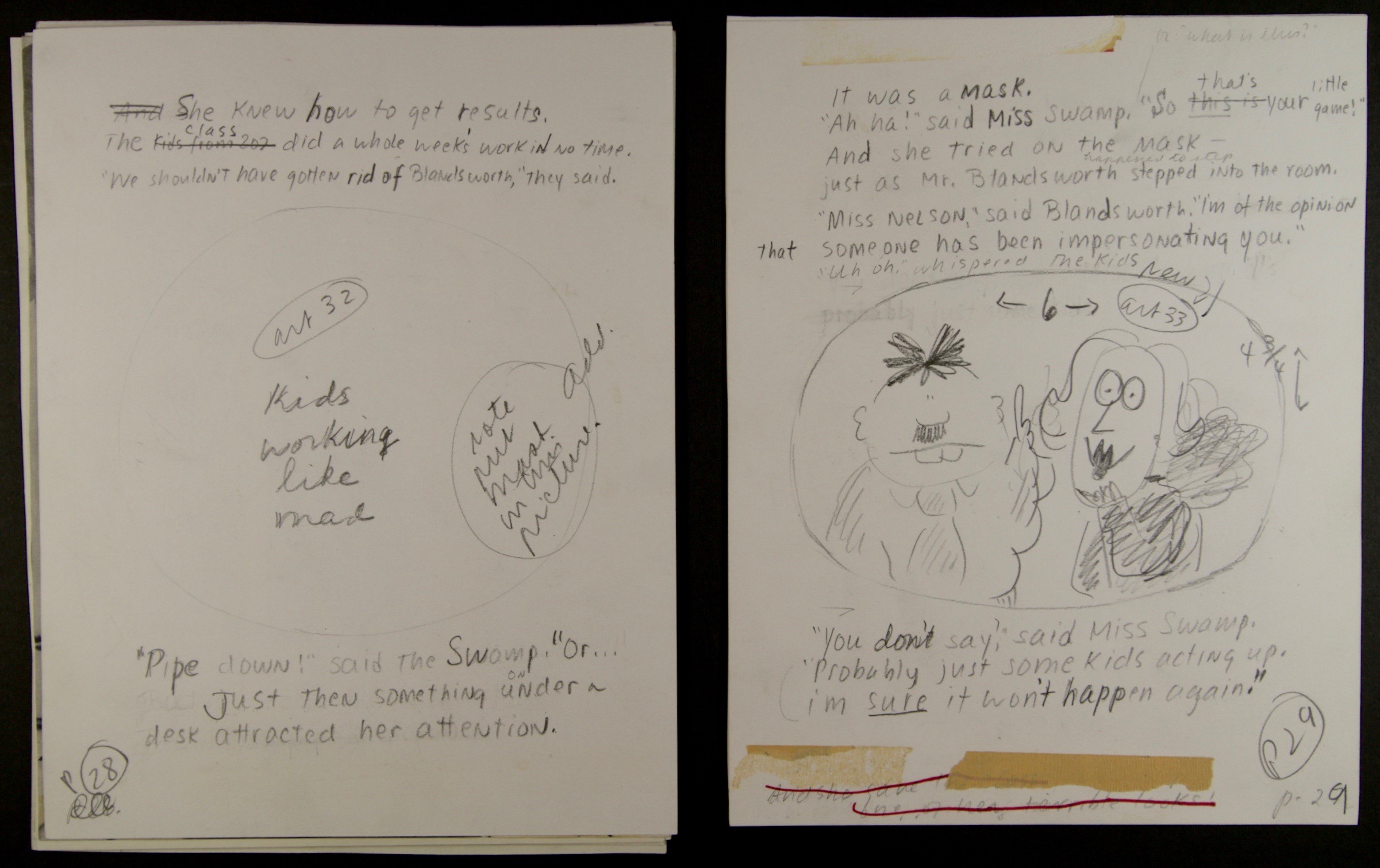

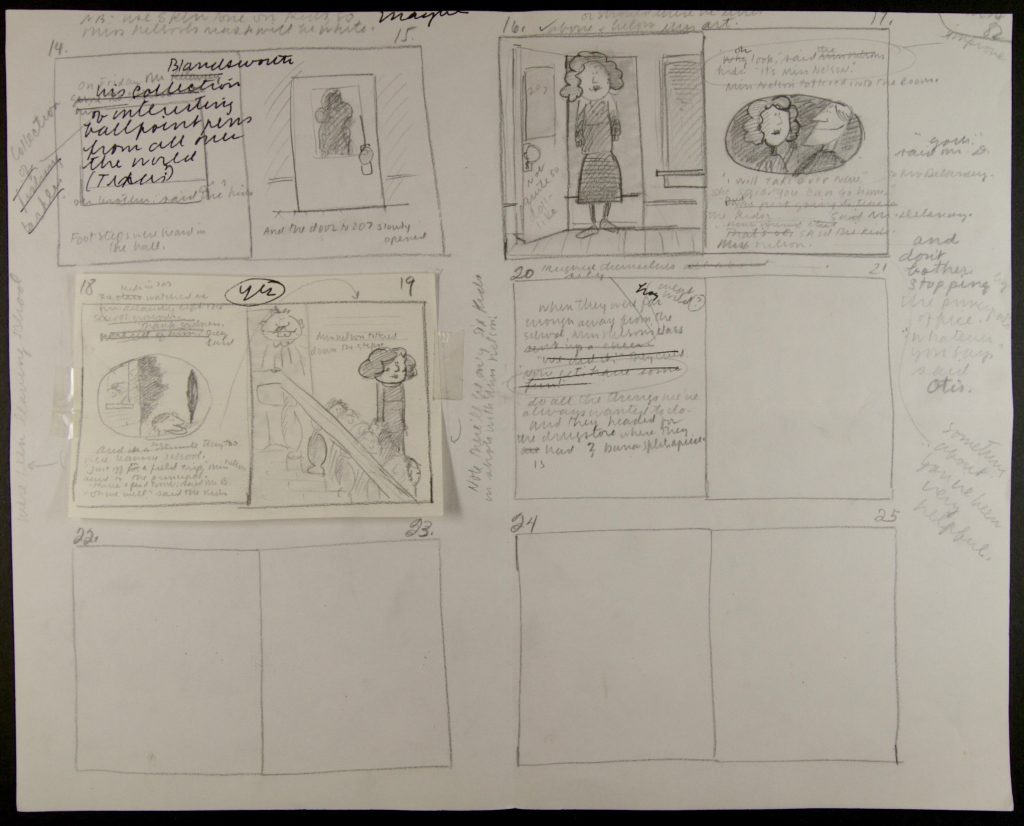

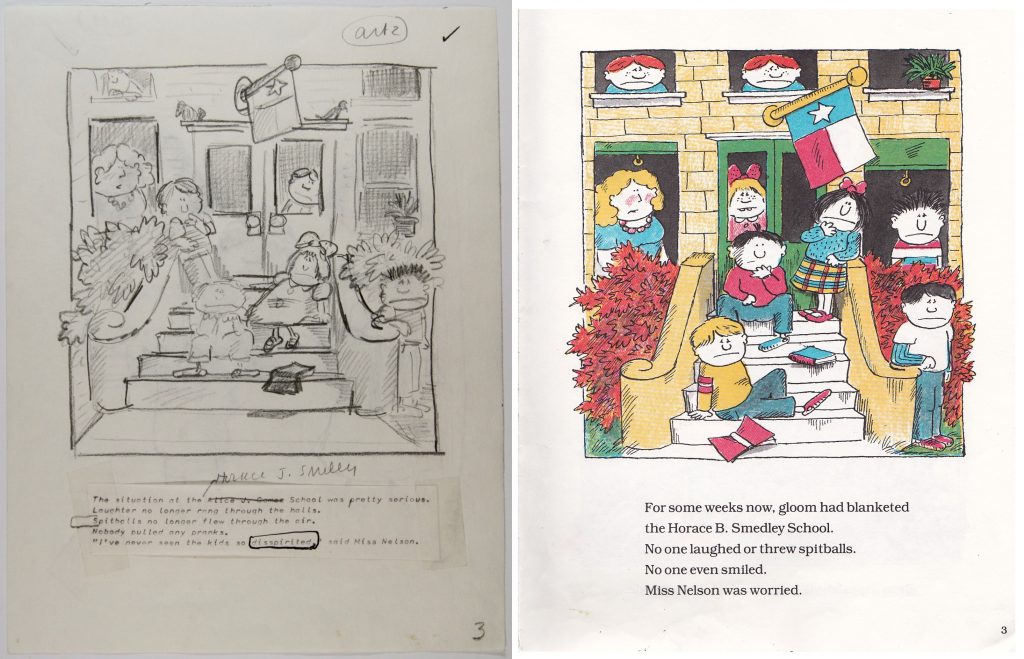

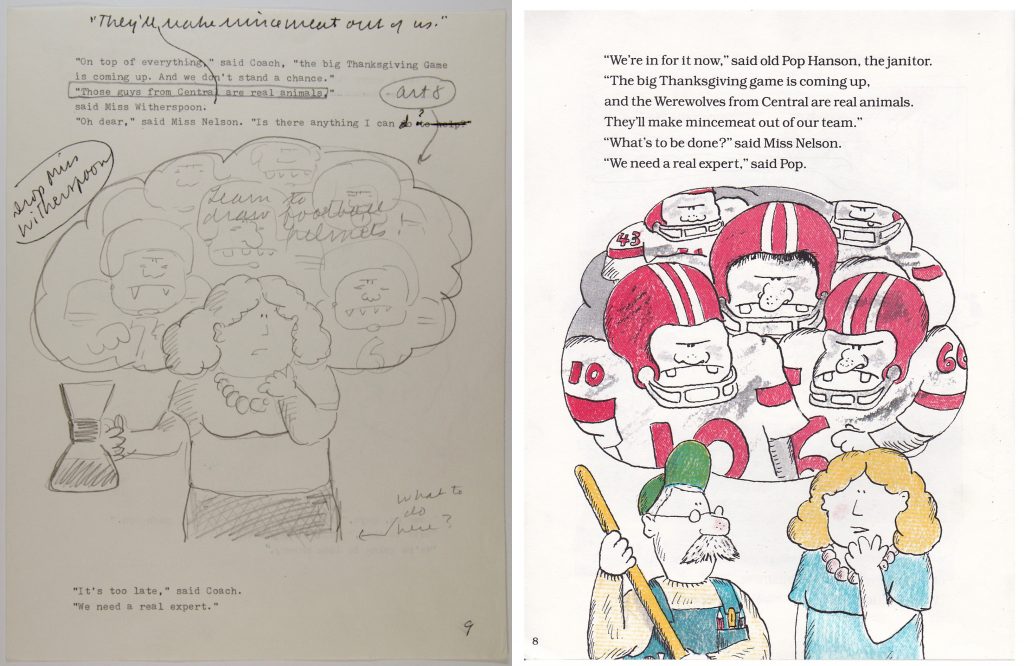

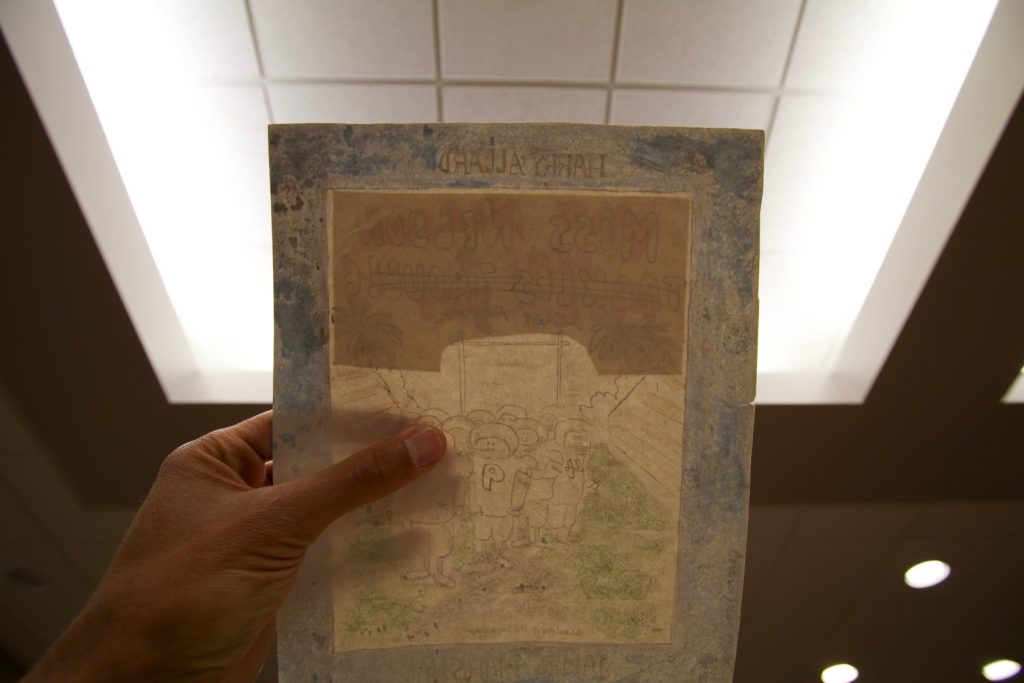

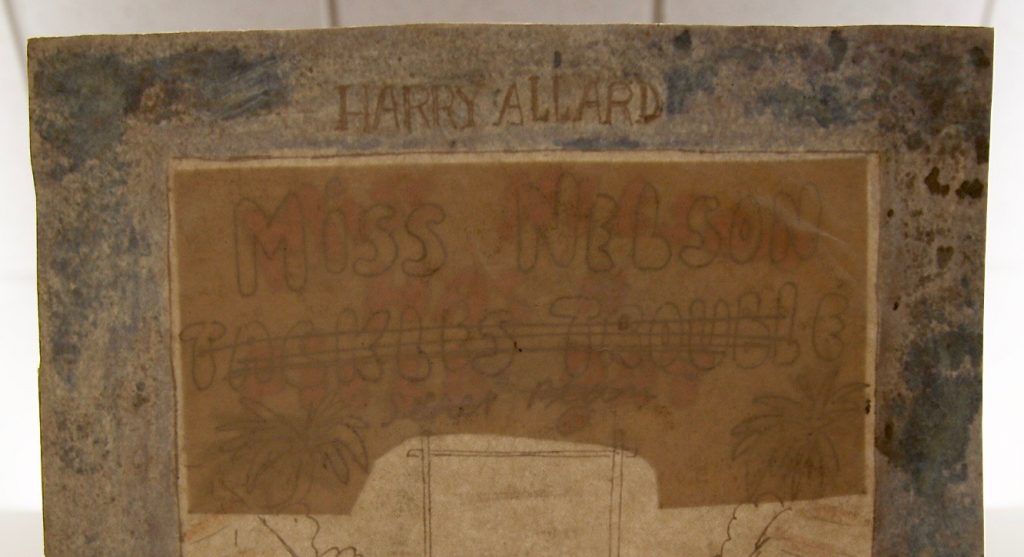

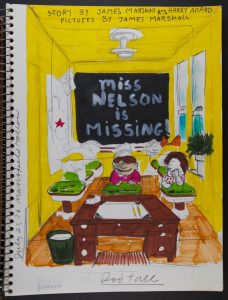

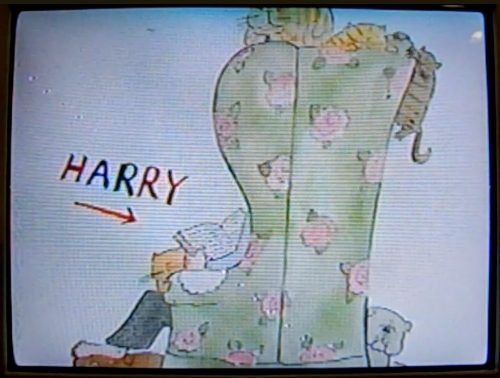

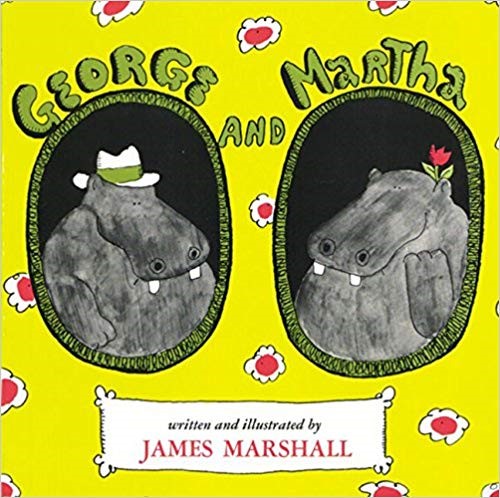

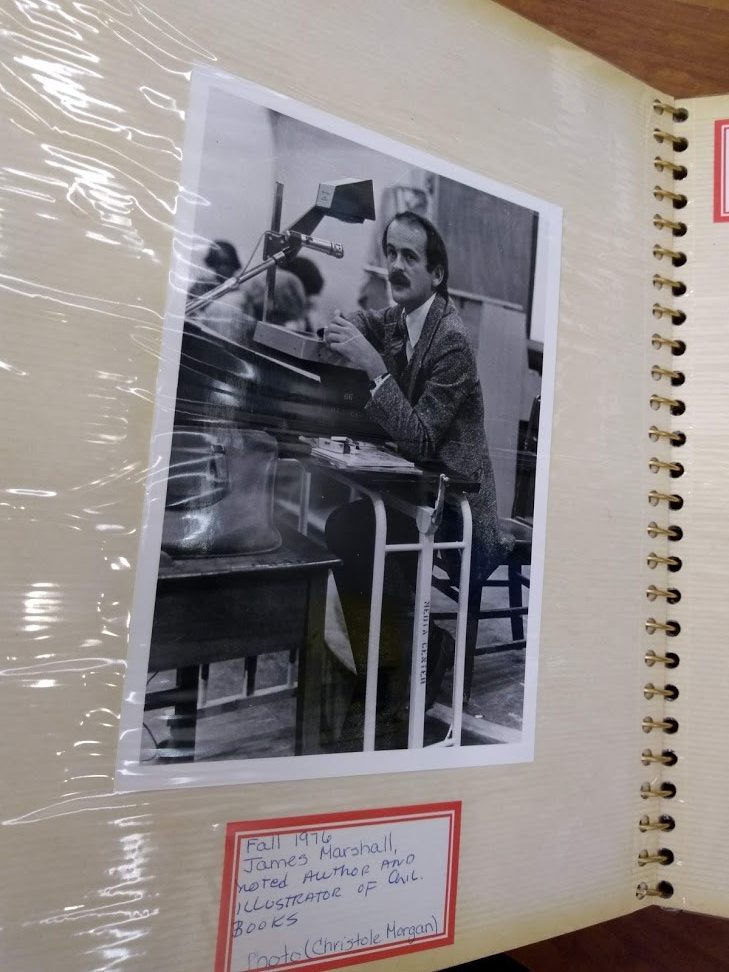

When you read a picture book you only see the finished product. When you visit archives, you see evidence of an often messy process, from sketches and sketchbooks to drafts, manuscripts, and original art. Occasionally you find very special pieces of media, like collections of audio cassette lectures. Francelia Butler was a professor of Children’s Literature at UCONN from the 1960s to 1990s and she invited dozens of authors, performers, and otherwise impressive thinkers to speak in her Children’s Literature 200 class, or as students referred to it, “kiddie lit 101.” She had the foresight to record most of these lectures which are now housed in the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection. James Marshall lived a couple of miles from the UCONN Storrs campus and would give a yearly lecture to her class of primarily undergraduates from 1976-1990 when he was 34 to 48 years old (he died when he was 50). These lectures are mostly off the cuff; he reads a book aloud (often George and Martha or The Stupids), discusses how he came up with ideas for books like Miss Nelson, then takes questions from the audience.

Marshall is the perfect guest lecturer. He is funny, insightful, knows how to work a crowd, and best of all he’s a generous lecturer. He knows how to communicate ideas and make them accessible. At his core he was an educator; he worked professionally as one for a while, having taken over Maurice Sendak’s picture book making class at Parsons. Much of the insights he shares in these recorded lectures are still deeply relevant today, particularly in terms of the creative process and the job of a children’s book creator. Marshall agonized about writer’s block and felt the pressure to make money. He also spoke from the perspective of an outsider who worked extremely hard and never took the joy of making books for granted.

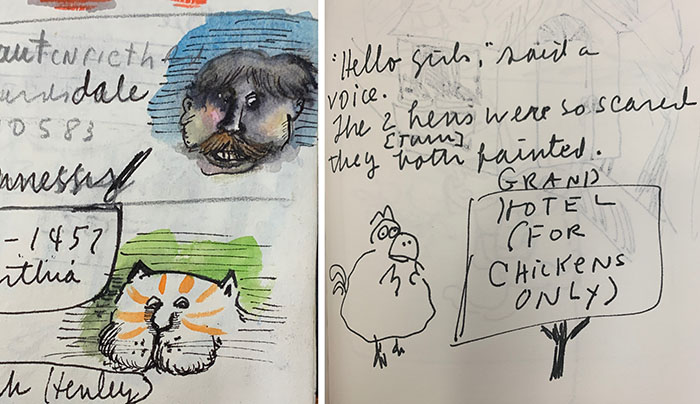

When I arrived at UCONN to start my fellowship I didn’t anticipate that most of my time would be spent using my ears rather than my eyes. I had spent three weeks in 2018 at the Kerlan Collection looking through dozens of his sketchbooks in their collection and since then have tried to read all of his books. I realized I was engaging in a bit of detective work, trying to put the pieces together of a fascinating, talented, funny creator through the crumbs he left behind. Hearing him talk about his work (getting a firsthand narrative) made me feel incandescent. I popped in one cassette after another and was grateful for my fast typing (as of the time of this blog post’s publishing only two of the cassettes have been digitized; according to the archivist it’s an expensive and laborious process). In this post I’m going to share some quotations from these audiocassettes, what surfaced for me as a picture book creator, and what I think other people in the field might find interesting, from his process to how he thought about creative work.

“I start off drawing. I develop a character, make it as crazy as I can, and put that character in a situation. I start with a visual. I couldn’t sit at a typewriter and start a story with words… Drawings first, and then I type it up” (1977, cassette 504). Marshall was known for his strong characters; consider George and Martha, Fox, or The Stupids; the story revolves around them and how they interact with other characters. It’s not so much about plot; Marshall at one point describes George and Martha as a comedy of manners. “I teach my kids at Parsons that to start out you must have a very solid rounded character that lives. I have lots of sketchbooks and I just develop characters as they go along” (1982, cassette 515). Marshall trusted that a good story would organically come out of a good character, particularly if put in an interesting situation where they have to react. There’s a sort of faith required in starting with a character; you don’t know who’s going to show up on the page. You get to know a character by the way they look, their gesture, and how they react to other characters.

Marshall didn’t discuss a specific method that he used to generate stories because he didn’t seem to have one. He described working intuitively, relying on his brain and hand to put together funny ideas. “People ask me often where the ideas come from. If I knew that I could probably spell it out to you… I don’t know where the good stuff happens. It happens when I work a lot, and late at night. Usually If I’ve been working 8-10 hours doing just mechanical stuff I’m so tired all my defenses are down. I’m not worried whether it’s going to be a success or not, and some nutty idea comes in, it’s like someone else told me that… You know it came from inside your head but you don’t know why or how” (1979, cassette 506). “What I do is try to sit down, and if I fall down and start laughing that’s a good sign” (1980, cassette 508). It seemed that he didn’t examine his story-making because he was worried that if he figured it out he would lose the muse. “What I do is intuitive and I don’t know why I’m sitting here talking to you because I don’t really know why I do what I do, and to talk about it is a little scary to analyze it. I’m afraid if I look at it too much and try to figure out what I do it’ll go away” (1985, cassette 525). Since he relied so heavily on intuition his fear of losing the muse makes sense. He mentioned this fear in several lectures, and it seems to really be the thing he feared the most: the bucket going down the well and coming up dry.

Perhaps this fear came from a sense of what we would now describe as imposter syndrome. “Often I have so much trouble coming up with endings. It’s just like hell. Because you think here I am, this is what I do for a living, but maybe I’m not so good anymore, maybe I never had any talent in the first place” (1987, cassette 527). Marshall continues in a 1990 lecture, “I’ve thrown up in my studio from the fear of thinking I’m all finished, I’m washed up, I have no talent, I can’t even write one of these dumb books, I can’t think of another joke” (cassette 531).

Perhaps it came because making good books for children is deceptively challenging. There isn’t a roadmap, particularly when you’re making something that pushes boundaries of humor, style, etc. “When I’m drawing it’s like heaven, even when it’s not going so well I’m really, really happy. I feel connected, I feel like I belong. Why it’s such hell to get started, I don’t know. I guess it’s because I’m scared. Chekhov had the same feeling, he thought he was no good, couldn’t cut it. If a guy that great can have those feelings maybe it’s not so abnormal, maybe you should have those feelings of insecurity. Because if you’re absolutely sure that what you’re doing is brilliant what you’re doing is copying yourself or copying someone else” (1988, cassette 529).

Or perhaps the pressure was more external; he needed to make more books in order to keep his career (and income stream) flowing. This is when his practice of writing intuitively probably chafed against a demanding publishing schedule. “I have an artistic problem: when a book is successful, editors like to see success perpetuated, so they hire you to do a sequel. I’ve done so many sequels but I haven’t gotten any quite right. It’s the hardest thing in the world to capture the spirit of another book when you don’t have an idea. I’m doing three picture books, all three are sequels, and I’m stalled on all three. It’s a sickening feeling to think that you’re going to have to turn that money back and that you’ve run out of ideas” (1985, cassette 525). Marshall’s output was prodigious; he made around eighty picture books during his 50-year life. What is the result of working faster than your machine wants to run? The quality may suffer, at least in the creator’s eyes. In one lecture Marshall says, “I’ve made 60 books and only about 20 am I really proud of” (1983, cassette 517).

Marshall’s writing and drawings have a sense of lightness and ease to them, particularly in the way he draws characters and communicates their emotions through their eyes (often simple dots). In 1997 several years after Marshall’s death, Sendak wrote in the New York Times, “Much has been written concerning the sheer deliciousness of Marshall’s simple, elegant style. The simplicity is deceiving; there is richness of design and mastery of composition on every page. Not surprising, since James was a notorious perfectionist and endlessly redrew those ”simple” pictures.”

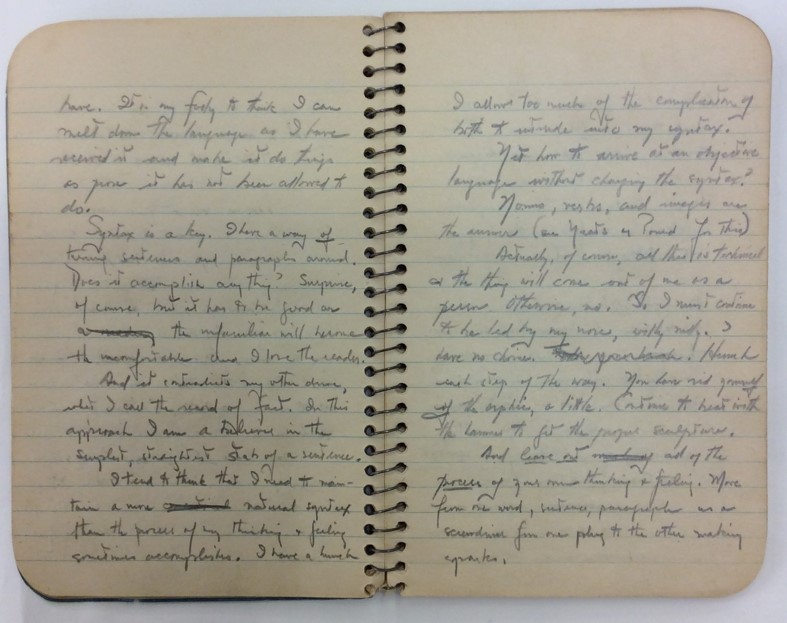

Marshall drew with joy, and this is most evident in UCONN’s collection of his sketchbooks. In his lectures he talks about the phenomenon I hear a lot of other author-illustrators experiencing when they move from sketches to final art; some freshness is lost. “It’s when you have to prepare something that’s going to get published, at least not only me but everyone I know in the business, you get tense and frightened because this is going to be out there, there are going to be 20,000 copies of this, and it gets tighter and tighter. The best stuff I’ve done of any quality is in my sketchbooks and I pick that stuff out and I’m like why can’t I do that here?” (1984, cassette 520). Perhaps it’s different when you’re making final art because you know that you have an audience, that you’re relying on the art to make money. It’s less about amusing yourself; it goes from a private activity to a very public one. “The sketches are so much more interesting, that’s the fun part. It’s when you do a line that you know is going to be published you start to clutch and tighten up. I’m just now learning to do books and get a line that’s going to be published that’s as good as the one in the sketches. I’d love to take my old sketches out and publish them. I feel so much more comfortable with them. I don’t know if it’s a fear of success or fear of failure, it’s a really terrifying process to go through” (1981, cassette 511).

Marshall also shared insights into how he thought he was perceived by gatekeepers of the industry, specifically librarians who had a more traditional sense of illustration and who also reviewed books and selected for awards (in particular the Caldecott Award). “I work in basically creative periods of about 3 weeks that’s all I can stand… This is dangerous because when I tell librarians (“conventional people”) if I tell them how short it takes me to do a book I can see in their eyes my stock going down. You have to tell them you worked 5 years on this book and you’ve drawn with the blood of your slaughtered children and then it’s a masterpiece” (1985, cassette 519) Marshall drew somewhat injured and bitter conclusions about why he had been overlooked, “People who are in children’s books are ashamed of being in children’s books. People on committees want to pick a book that shows they’re an important, art-minded profession” (1985, cassette 519).

Sendak wrote that Marshall “paid the price of being maddeningly underestimated — of being dubbed ”zany” (an adjective that drove him to murderous rage)… he was dismissed as the artist who could — or should or might — do worthier work if he would only dig deeper and harder. The comic note, the delicate riff were deemed, finally, insufficient. James knew better, of course, and he was right, of course, but he suffered nevertheless. There was nothing he could do to impress the establishment; that was his triumph and his curse. Marshall did fulfill his genius, and its rarity and subtlety confounded the so-called critical world. The award-givers were foolish enough to consider him a charming lightweight, and when Caldecott Medal time came around, they ignored him again and again.” Marshall also spoke about competition in the children’s literature world, which undoubtedly was connected to him not feeling appreciated, validated, or celebrated by the people who held power. “The world of children’s books I used to say is a nice world. It is not, it’s a nest of vipers, we all hate each other… we’re very competitive” (1982, cassette 513).

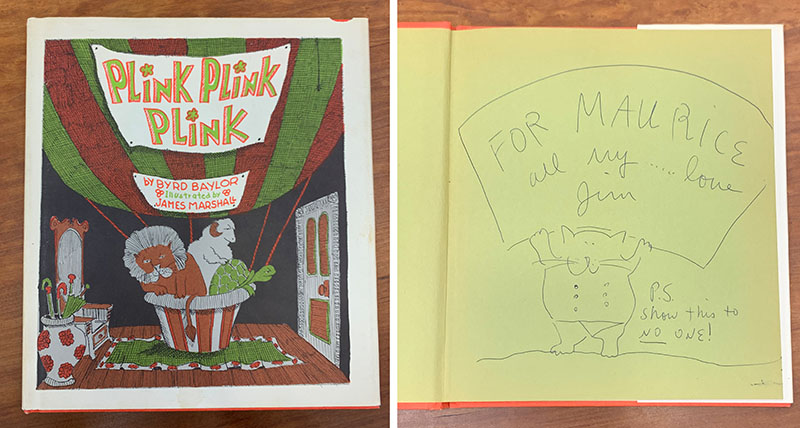

It was interesting to hear Marshall talk about the other authors and illustrators he was in community with. In nearly every lecture he named some of the people who he thought were doing the best work in children’s literature: Arnold Lobel, Edward Gorey, Maurice Sendak, Tomi Ungerer, Rosemary Wells, William Steig, Edward Ardizzone, and Quentin Blake were all mentioned. “If you want to see some magnificent small jewels, look at the Frog and Toad books. I thought, oh I can do that. First I saw Sendak: oh, I can do that. Lobel: oh I can write stories about two friends too. They sort of gave me confidence. I didn’t know how hard it is. Sometimes it’s fun, sometimes it’s impossible to try and write two-page stories with a beginning, middle, and end” (1990, cassette 532). He clearly adored Maurice Sendak, who he referred to as “the granddaddy of us all” (1980, cassette 508) in terms of contemporary illustration. The Maurice Sendak Collection of James Marshall at UCONN contains several of Marshall’s books that he inscribed for Sendak, including a rare copy of his first illustrated book, Plink, Plink, Plink (1971) by Byrd Baylor which Marshall said “sunk, sunk, sunk” due to the “awful poems and awful pictures” (1977, cassette 504).

This collection of recordings is a very rare and special item; you just don’t find a lot of authors speaking in their own words, at length, about their work. I think that this speaks to Marshall’s experience as an educator; someone who has good communication skills, a sense for what might be interesting content, respect for their audience, a willingness to be generous with the knowledge they possess, and their love for the work.

One of my favorite things that Marshall said had to do with the joy of getting to do the thing you love most in the world as a job. “To be able to support myself by doing what I really like to do best and by being creative, I never dreamed that that could be. I was raised with protestant puritant [sic] ethics. In Texas you had to bring home the bacon by doing stuff that you hated; my daddy hated his job, my mama hated being a housewife, everyone in my family hated everything. I thought when I became an adult I had to just swallow it. It’s not true. It’s a wonderful, wonderful feeling” (1983, cassette 517). This is something that you can easily lose sight of a children’s book maker as you get involved in the day-to-day of trying to meet deadlines, negotiate with art directors, redo cover art, schedule school visits, make money and budget wisely, etc. I’m writing this blog post in late spring 2020 in the midst of a global pandemic which has made clear that nothing is guaranteed, in particular human life, especially those most vulnerable in our society. For a while I wasn’t sure if books or art even mattered. But of course they do, and the act of engaging in joyful creative work is a much-needed lifeline, as Marshall attested to during his short life, ended by the HIV/AIDS pandemic in 1992. “One of the most wonderful things in the world is to do creative work, it is the greatest high, it makes your life come together” (1987, cassette 527).

Pea Soup and Pink Loafers

The following guest post is by Elizabeth Barnett, recipient of the 2019 Billie M. Levy Travel and Research Grant. Ms. Barnett is an assistant professor of English at Rockhurst University in Kansas City, where she is the director of the Midwest Poets Series and editor of the Rockhurst Review. Her essays and poems have appeared in Modernism/modernity, Gulf Coast, and The Massachusetts Review. She is working, with great pleasure, on Marshall’s literary biography, tentatively titled Egads!

“But how then can you really care if anybody gets it, or gets what it means, or if it improves them. Improves them for what? For death? Why hurry them along? Too many poets act like a middle-aged mother trying to get her kids to eat too much cooked meat, and potatoes with drippings (tears). I don’t give a damn whether they eat or not.”

—Frank O’Hara, “Personism”

James Marshall’s voice had two kinds of drawls, the homey “ahs” of his Texas childhood—“I was told y’all are shy. You can’t be any shyer than I am”—and the playful “ohs” of the queer, East Coast communities he moved to soon after—“I live in New York as well as Connecticut and I go to galleries all the time and everything I see in painting is soooooo dull, suuuuuuch crap.” Marshall’s voice maps his identity. It also conceals it. A voice, as opposed to the words it speaks, can’t be “on the record,” so can supplement, complicate, and contradict those words.

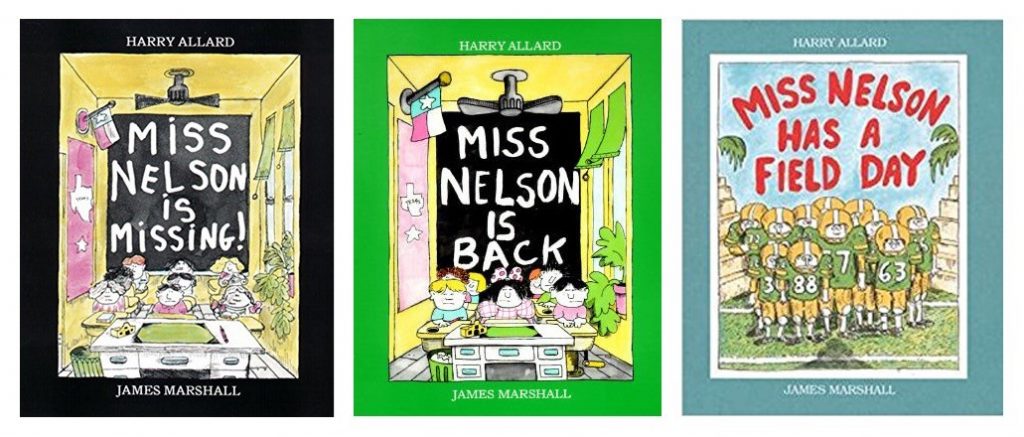

I knew Marshall’s authorial voice—witty, warm, and weird—from gentle hippo friends George and Martha; sweet teacher Miss Nelson and her witchy alter ego, Viola Swamp; and the tragiocomedic Stupid family.[1]

More than 25 years after his death, I came to know Marshall’s actual voice when University of Connecticut archivist Kristin Eshelman guided me to an amazing and extensive cache of recordings. From 1976 to 1990 Marshall visited his friend, one-time landlady, and devoted admirer, Francelia Butler’s “kiddie lit” class most semesters, reading his stories; chatting about the art world, publishing industry, and their intersection in picture books; and, most revealingly, participating in Q&As. Thanks to the generosity of Billie Levy and the University of Connecticut Libraries, I was able to listen to the run of these tapes, which begin at the peak of Marshall’s career and end two years before his death of complications from AIDS.

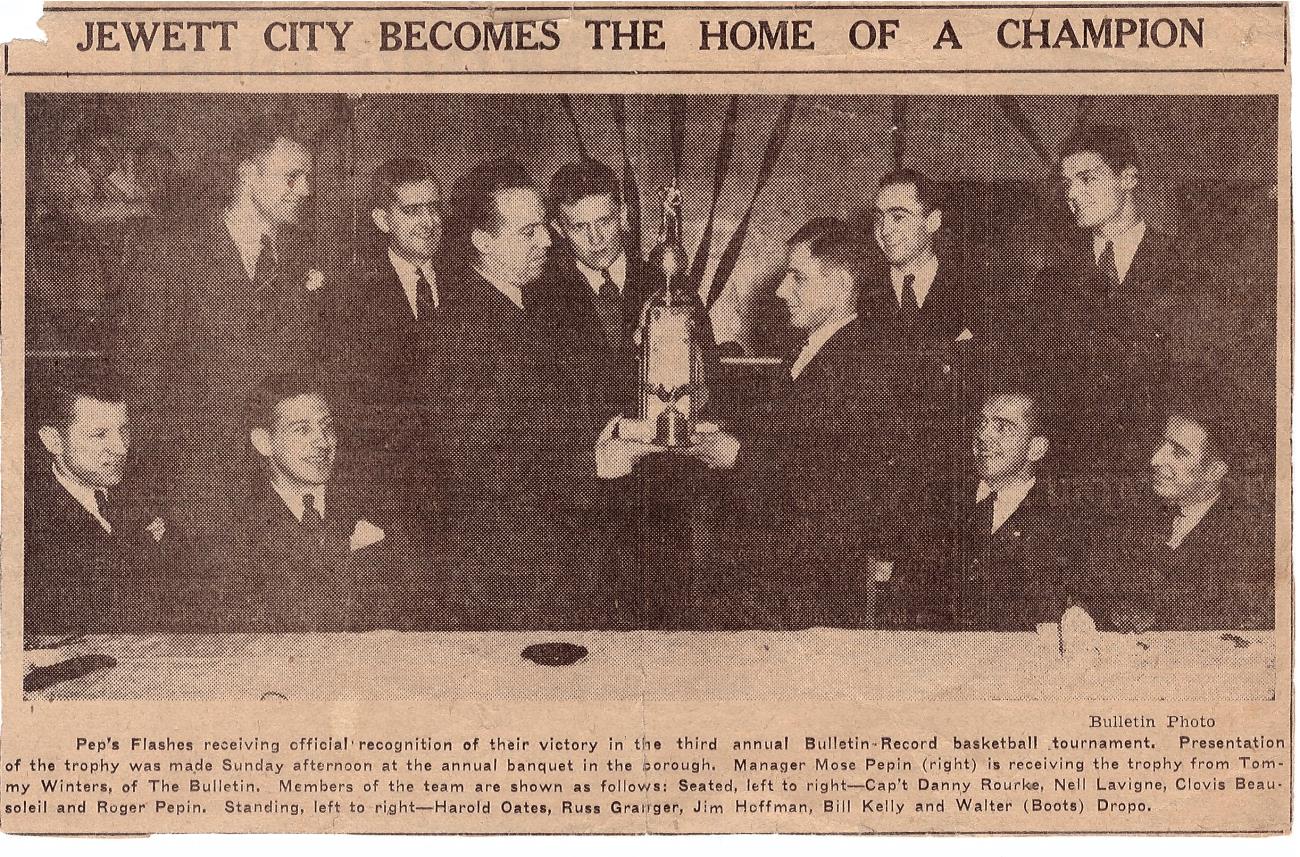

Marshall’s first visit, from the Fall 1976 class photo album. (The class made a photo album!). Francelia Butler Papers, Archives & Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library

A question I had for the tapes: how did Marshall navigate being a gay artist at a time when it was, full stop, impossible to be an openly gay man making books for children? Eavesdropping on those Regan-era, AIDS-blighted years, I never heard Marshall say he was gay. He never spoke as though he weren’t. Marshall’s authorial persona, distilled in his voice, suggests a key insight about his books, which also had to straddle the line between authentic artistic creations and market-dictated norms. What he says and how he says it are analogous to the words and pictures in one of his books. The voice says what the words can’t, just as the pictures, at times, undercut the moralistic conventions of children’s literature.

In Butler’s classroom, for example, I heard Marshall gesture to the limits of what he was allowed to say in an October 10, 1979, interaction with a female student. The student asked if Marshall was married. Marshall answered first with several beats of silence, then with a single word, “no,” then another beat of silence, then “I’m not” followed by a dismissive “next question.” The question asker perhaps wanted to catch Marshall out or perhaps didn’t understand what Marshall’s voice had been telling her. She asks an “innocent,” superficially unobjectionable question. But that banal surface hides (or not) the power of the dominant culture that the question summons. It really asks: Are you one of us? The asker uses the language of power and Marshall subverts that language by making it superfluous, his answer conveyed through silence and tone, not the words themselves.

This brief interaction reminded me of “Split Pea Soup,” the first story in 1972’s George and Martha, Marshall’s first book as both author and illustrator. It begins, “Martha was very fond of making split pea soup. Sometimes she made it all day long. Pots and pots of split pea soup.” These three simple sentences amplify each other and give a sense of something a little off about Martha’s soup making, the repetition mirroring Martha’s repetitive actions, recasting conventional domesticity as a less-cozy compulsion. Why is she making soup all day long? Why is she making so much? What begins in a normal place ends in a slightly absurd one. Or perhaps it’s just that the absurdity of normality comes through in the repetition. In the illustration, the framed slogan “Soup’s On” underlines Martha’s extreme enthusiasm for soup.

James Marshall, George and Martha

The illustration shows Martha, a hippo, in a massive checkered apron tied with an equally massive bow. She wears no other clothes. Her performance of femininity draws attention not to her femininity but its status as performance. (Here I echo and Marshall anticipates Judith Butler’s theorization of performativity). She is a topless large animal playing the part of a demure housewife. A drawn border surrounds the image, emphasizing that, like Martha in the kitchen, the book itself is performing. The redundant border puts “children’s story” in quotation marks by not allowing the page itself to function as the boundary, by insisting on something more artful, and by drawing attention to that artificiality.

So Martha loves making soup. We then learn that George hates split pea soup but eats it anyway to make Martha happy. However, he’s only hippo and reaches a point where he can eat no more. How, though, can he tell Martha that this good, normal thing she’s doing makes him miserable? He can’t—he pours the soup into his loafers. His pink loafers. And Martha catches him.

James Marshall, George and Martha

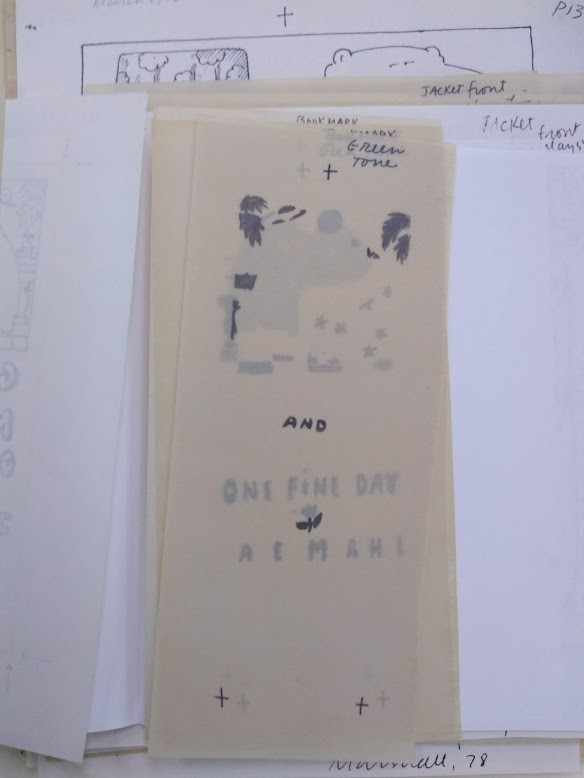

“Light in his loafers” was a common euphemism for homosexuality in the mid-century heyday of loafers and sexual repression. Pink is coded as female or gay. Until a new, more economical method of full-color printing was pioneered in Japan in the mid-1980s, most of Marshall’s illustrations were color overlays, which means that Marshall drew the picture then traced each thing that he wanted to be yellow, or blue, or red onto separate sheets of paper and colored those in with graphite, indicating if any colors were to be diluted by giving the percentage of that color to be applied. All to say, the pink was absolutely a deliberate choice.

Example of color overlay from George and Martha One Fine Day. de Grummond Children’s Literature Collection, University of Southern Mississippi.

George’s disposal of the soup in his loafers might be read as a symbolic refusal of compulsory heterosexuality. It is also a refusal of language, suggesting the complicity between the two. George “says” he hates the soup through his actions because language would imbricate him in the very power structure he’s resisting. I see Martha as the question-asker here. She is playing the feminine role as she’s supposed to. She’s aligned with the dominant culture. George is Marshall; he can’t tell Martha he hates the soup because here she is doing exactly what she’s supposed to do (however inane), and he’s messing it up. George avoids the language trap just as author/illustrator Marshall does—they don’t put the subversive part into words.

The too-pat ending of “Split Pea Soup,”—Martha tells George, “Friends should always tell each other the truth,” and they eat chocolate chip cookies—to me signals that Marshall wants his reader to feel the tension between what the story says and what it means. I probably think that because that’s what I hear happening in the classroom interactions on the archive’s audio tapes. Marshall’s language, punctuated with strategic silences and curtness, insists on its own inadequacy, drawing an arrow to what’s left out. The story’s sharp turn to the didactic reads to me like the drawn border around the illustrations. It signals its own performativity, here of the norms of the picture book, which are weakened, rather than reinforced, by their inclusion.

Frank O’Hara’s 1959 critique of poetry-as-moral-vitamin anticipates Marshall’s later refusal of children’s literature’s didactic imperative. In both cases, queer writers already existed outside of mainstream culture, their morality maligned by that culture. It follows they may have been especially wary of the inherent value of literature being used for ethical indoctrination. Both suggest the value of their art form is not the moments it teaches us something, but the moments it refuses to.

In 1979 Marshall “answered” the student

question with words that would not endanger his art and livelihood. Marshall’s delivery suggests he wants the

audience to know that’s why he’s saying them. The performative conformity is

one way to understand the more conventional moments in Marshall’s startlingly

original body of work. He tells us when he’s playing by the rules to protect

the magic of when he’s not.

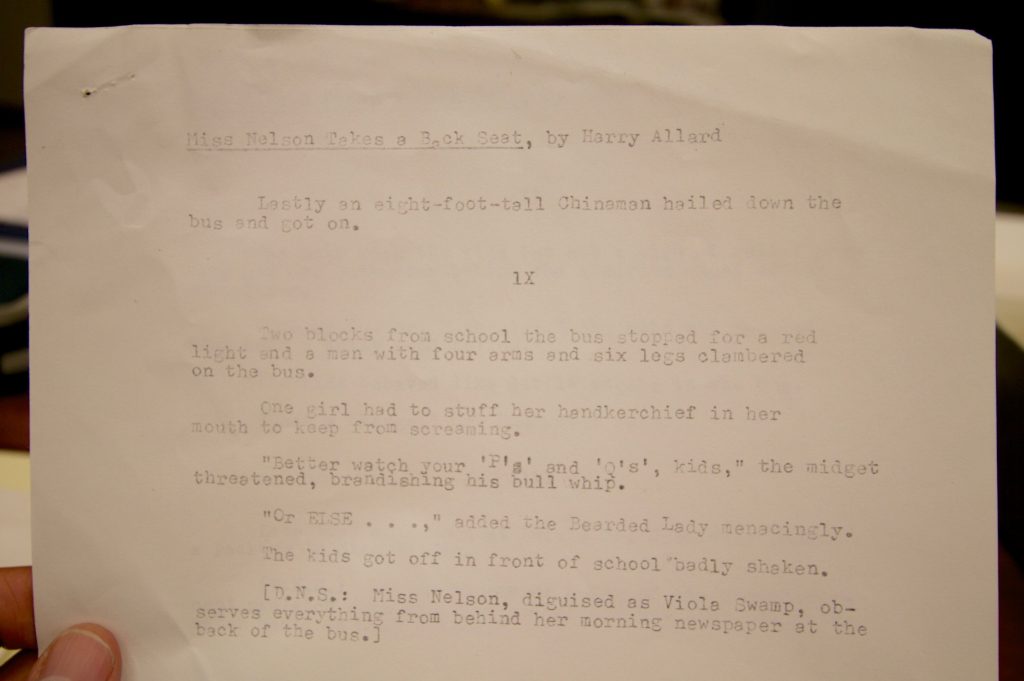

[1] The latter credit Harry Allard with authorship but, as Jerrold Connors convincingly argues in his post on this site, and Marshall’s materials confirm, Allard often provided the creative spark for a piece, but Marshall shaped the narrative and the finished prose.

“Thinking with my hands” in the Archive: Second Generation New York School Gems

Currently a postdoctoral fellow in the School of Literature, Media and Communication at Georgia Institute of Technology, Dr. Nick Sturm is an Atlanta-based poet and scholar. His poems, collaborations, and essays have appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, PEN, Black Warrior Review, The Best American Nonrequired Reading, and elsewhere. His scholarly and archival work on the New York School of poets can be traced at his blog Crystal Set. He was awarded a Strochlitz Travel Grant in 2018 to conduct research in the literary collections, including the Notley, Berrigan, and Berkson Papers, that reside in Archives and Special Collections.

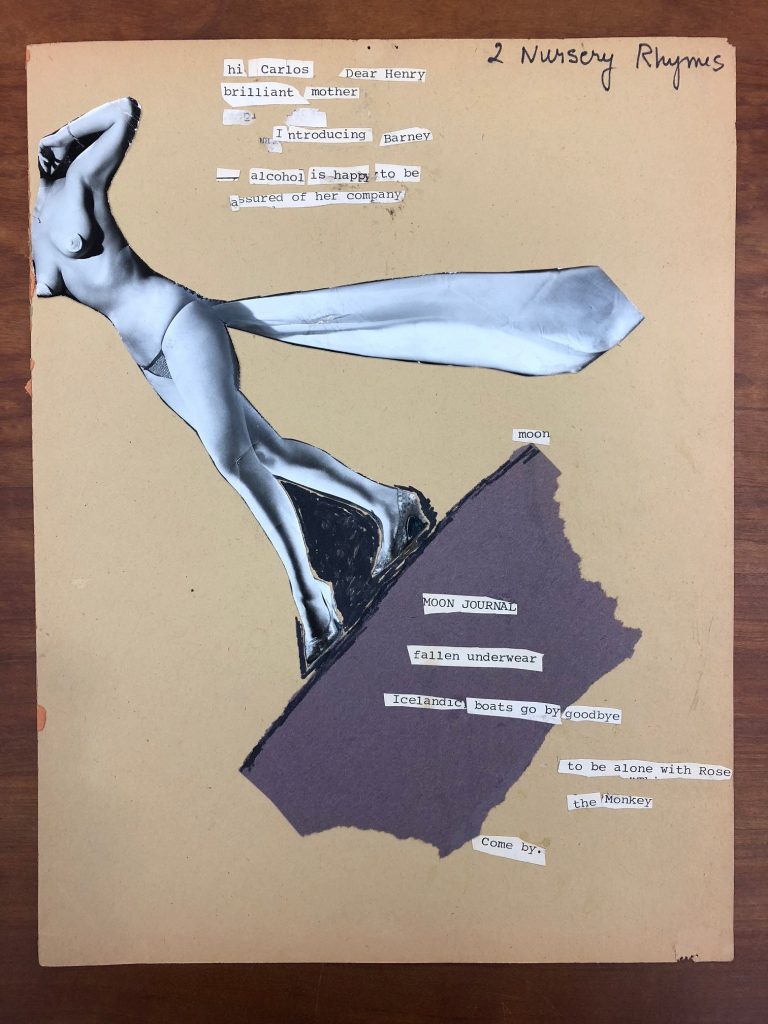

In my first-year writing course at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta where I teach as a Marion L. Brittain Postdoctoral Fellow, my students are reading books by Second Generation New York School poets to critique and creatively reimagine concepts of youth, coming-of-age narratives, and the overlap between do-it-yourself and avant-garde aesthetics. We already read Joe Brainard’s I Remember and Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets, two versions of youth, memory, and selfhood constructed by male poets of the New York School, and were beginning to read Alice Notley’s Mysteries of Small Houses (1998) to extend this intertextual conversation about youth through the perspective of a female poet. While re-reading Mysteries, a book of autobiographical poems that tracks Notley’s “I” through the prismatic complexities of life and writing, I returned to her poem “Waveland (Back in Chicago)” in which Notley, challenged by the responsibilities and strictures of living inside concepts like motherhood and femininity in the mid-’70s, describes her process of collage-making, a practice Notley continues to be devoted to.

Frozen collection of world—this is “art” I don’t

write much poetry;

I’m thinking with my hands—a ploy against fear—

I have a pile of garbage on the floor

The poem then catalogs a series of collages with titles like “WATERMASTER” and “DEFIES YOU THE RHYTHMIC FRAME,” and also describes a collage composed of “a photo of a stripper I’ve named / Barney surrounded by cutout words she / dances to poetry.” Reading these lines, I remembered that I had actually just seen this collage in Notley’s papers at the University of Connecticut. Among a couple dozen collages by Notley, there was Barney herself, headless, cape trailing behind her, walking across a fragment of moon. After discussing this poem in class, I was able to show my students  the collage to talk about how seeing an example of Notley’s visual art helped us think about her critiques of femininity, motherhood, and aesthetics. Students were surprised that I had such an example to show them—what had seemed like a passing reference in a poem suddenly become material. They immediately started to describe the effects of juxtaposing the collage’s title “2 Nursery Rhymes” with the presence of a nearly-nude woman. They asked what it might mean for Notley to be a “brilliant mother” in association with the mythological feminine connotations of the moon. And they noted how the epistolary gesture that opens the collage’s text, “hi Carlos Dear Henry,” resonated with Berrigan’s The Sonnets, which is riddled with salutations like “Dear Marge,” “Dear Chris,” and “Dear Ron.” Seeing Notley’s collage projected in front of them, pairing the material evidence of the poem’s description with a conversation about how the visual medium supplemented their reading of the text, students said they felt a different connection to the poem, to Notley’s work, and to our entire discussion that day.

the collage to talk about how seeing an example of Notley’s visual art helped us think about her critiques of femininity, motherhood, and aesthetics. Students were surprised that I had such an example to show them—what had seemed like a passing reference in a poem suddenly become material. They immediately started to describe the effects of juxtaposing the collage’s title “2 Nursery Rhymes” with the presence of a nearly-nude woman. They asked what it might mean for Notley to be a “brilliant mother” in association with the mythological feminine connotations of the moon. And they noted how the epistolary gesture that opens the collage’s text, “hi Carlos Dear Henry,” resonated with Berrigan’s The Sonnets, which is riddled with salutations like “Dear Marge,” “Dear Chris,” and “Dear Ron.” Seeing Notley’s collage projected in front of them, pairing the material evidence of the poem’s description with a conversation about how the visual medium supplemented their reading of the text, students said they felt a different connection to the poem, to Notley’s work, and to our entire discussion that day.

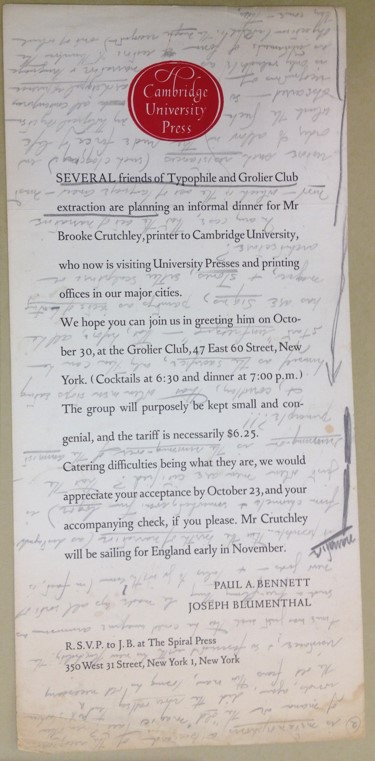

Of course, none of this would have been possible without my recent visit to the archives at the University of Connecticut. Thanks to the generosity of a Rose and Sigmund Strochlitz Travel Grant, I spent a week in the papers of poets and artists like Notley, Ted Berrigan, Bill Berkson, and Ed Sanders, among others, reading voluminous correspondence with Joe Brainard, Anne Waldman, Bernadette Mayer, Lewis Warsh, Ron Padgett, and a litany of other Second Generation New York School writers. Well-known for its Charles Olson Research Collection, the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center is also home to a wealth of materials associated with the New York School and is a necessary destination for any scholar of 20th century American poetry. And though a week of nonstop work in the archive allowed me to read and assess a lot of material, the sheer amount of New York School material stored at UConn, much of which has only barely begun to be utilized by scholars, meant that I was inevitably rushing through stacks of papers, quickly unfolding and refolding letters, swiftly scanning folder titles, and scratching my own nearly incomprehensible notes in a frenzied, focused attempt to see and catalog as much as possible before having to return to Atlanta. Like Notley’s description of collage-making in Mysteries, the archive is a place where I’m also “thinking with my hands” as I arrange, photograph, and order material in “a ploy against [the] fear” of overlooking or not knowing the full extent of what’s present in the archive. Every piece of material, like in Notley’s collage, is necessary and meaningful. This is how “a pile of garbage” becomes both art and scholarship. Starting with what you touch, a life and intelligence are animated.

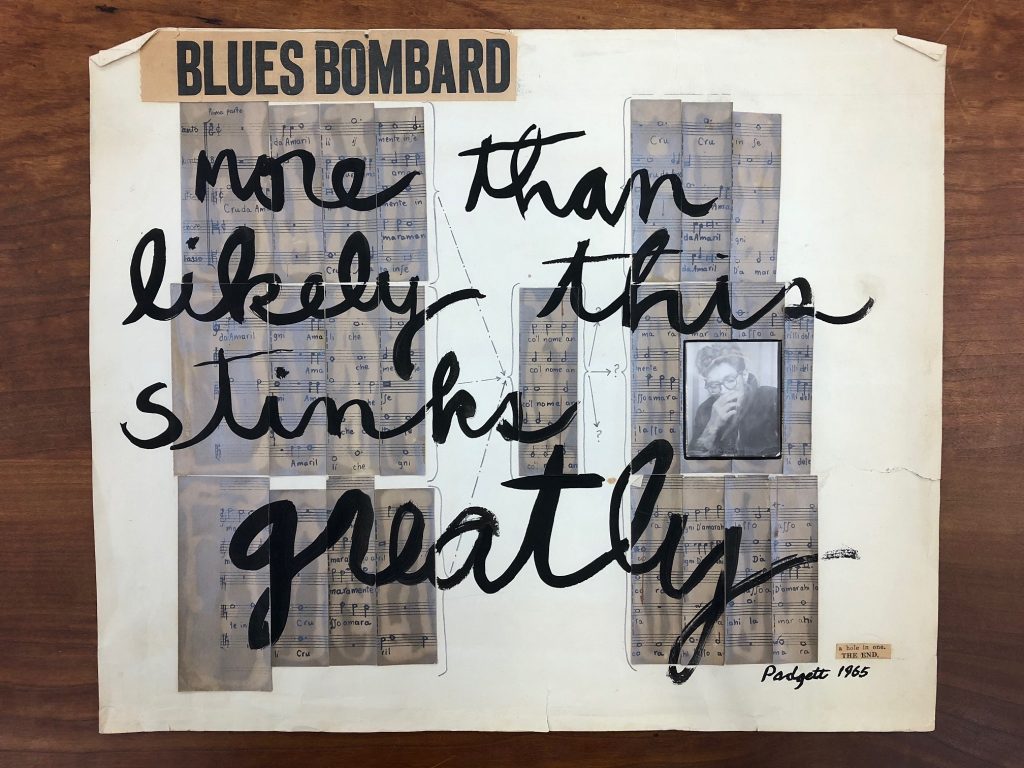

Notley wasn’t the only poet whose visual artwork is held at the University of Connecticut. Take this incredible poster-size collage “Blues Bombard” (1965) by Ron Padgett with the poet’s thick, elegant cursive painted over sliced fragments of sheet music that frame a photo booth portrait of Padgett, face half-obscured, cool, and mysterious. It’s rare to find visual artwork by Padgett that isn’t a collaboration with friends like Brainard or George Schneeman, and this piece is particularly astounding both for its size and the quick, pleasing, and humorous visual narrative that follows from the newspaper clipping-title, down across the rhyming and chiding main text ”more than likely this stinks greatly,” the arrows and question marks that logically and quizzically suggest a set of correspondences, the appearance of the artist mid-gesture, and the small, humorous, non sequitur conclusion “a hole in one. THE END.” It’s a lovely piece, and entirely Padgett in its cartoonish wit and simplicity.

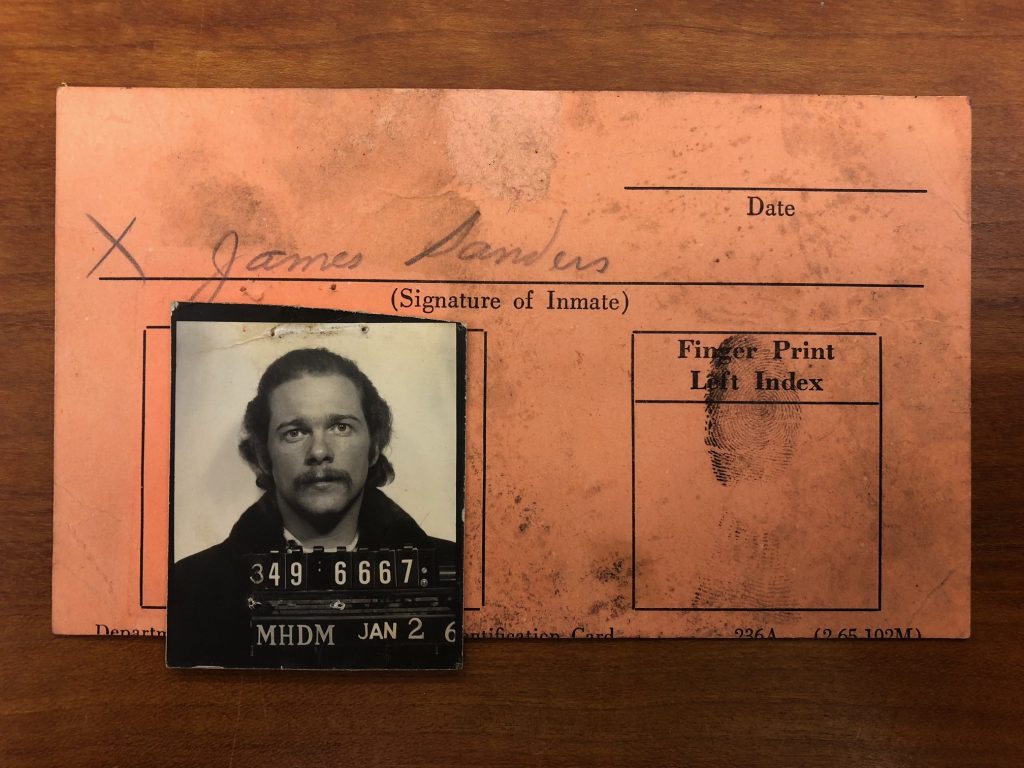

I was also interested to work in Ed Sanders’s papers at UConn, which includes a wealth of material from the Peace Eye Bookstore, the infamous “secret location on the lower east side” where Sanders’s mimeograph magazine Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts was published from 1962-65 until the store was raided by the NYPD on obscenity charges. Incredibly enough, the collection includes both a handwritten note from 1964 instructing Sanders to call an FBI agent and Sanders’s January 1965 mugshot following his arrest. After Sanders defeated the charges against him, Peace Eye temporarily reopened in 1967 with a Fuck You-style gala event auctioning off “literary relics & ejeculata from the culture of the Lower East Side.” The collection includes the handwritten notecards Sanders used to identify the various items for sale in the auction, like an “iron used by rising young poets to iron the buns of W.H. Auden during the years 1952-1966,” “Allen Ginsberg’s Cold Cream Jars,” and a letter—likely in protest—from Marianne Moore to Sanders in response to receiving a copy of Fuck You in the mail. Some of the material actually confiscated by the NYPD in the raid of the bookstore is in the collection as well, with the police evidence identification slips still attached, like a copy of a Joe Brainard drawing described by police as “Blue colored Headless Superman drawing with private parts exposed.”

I was also interested to work in Ed Sanders’s papers at UConn, which includes a wealth of material from the Peace Eye Bookstore, the infamous “secret location on the lower east side” where Sanders’s mimeograph magazine Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts was published from 1962-65 until the store was raided by the NYPD on obscenity charges. Incredibly enough, the collection includes both a handwritten note from 1964 instructing Sanders to call an FBI agent and Sanders’s January 1965 mugshot following his arrest. After Sanders defeated the charges against him, Peace Eye temporarily reopened in 1967 with a Fuck You-style gala event auctioning off “literary relics & ejeculata from the culture of the Lower East Side.” The collection includes the handwritten notecards Sanders used to identify the various items for sale in the auction, like an “iron used by rising young poets to iron the buns of W.H. Auden during the years 1952-1966,” “Allen Ginsberg’s Cold Cream Jars,” and a letter—likely in protest—from Marianne Moore to Sanders in response to receiving a copy of Fuck You in the mail. Some of the material actually confiscated by the NYPD in the raid of the bookstore is in the collection as well, with the police evidence identification slips still attached, like a copy of a Joe Brainard drawing described by police as “Blue colored Headless Superman drawing with private parts exposed.”

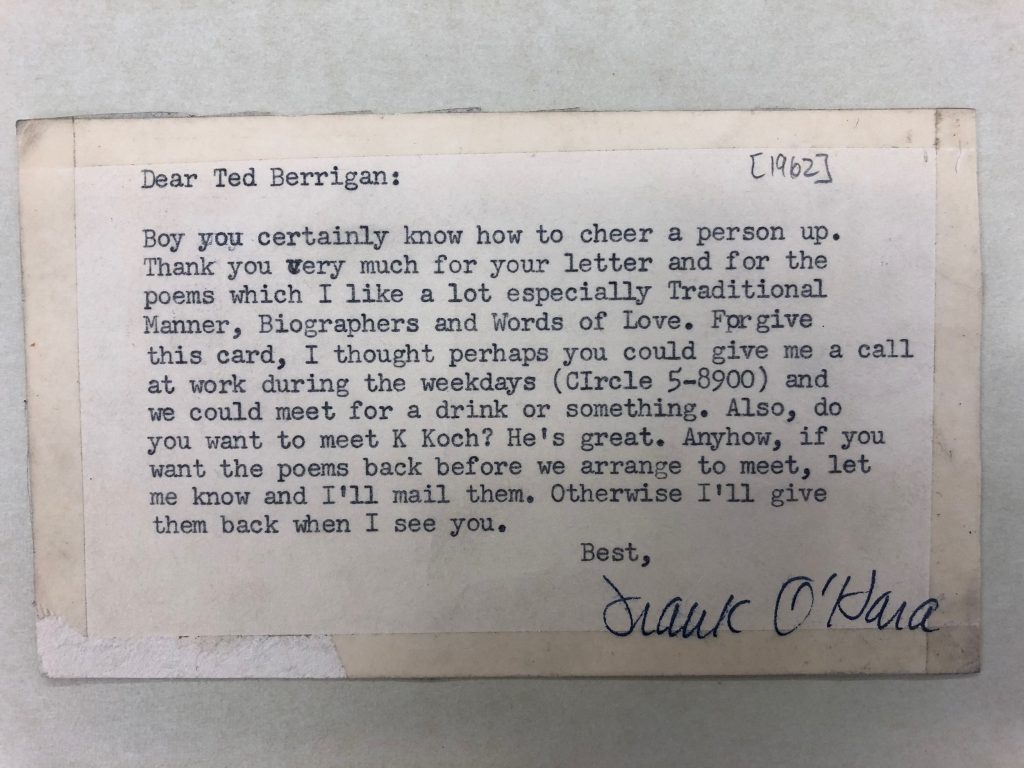

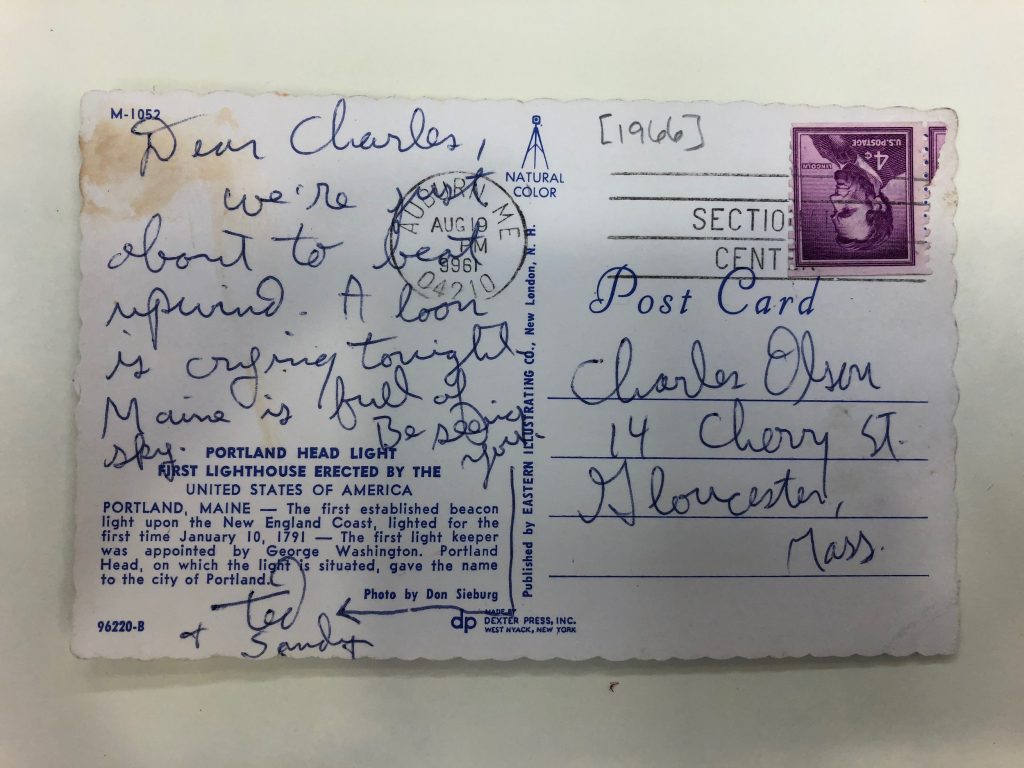

Among collages and obscenity charges, the New York School material at UConn also runs parallel to and benefits from the archive’s already well-known collections of Frank O’Hara and Charles Olson papers. The resonance of these collections is embodied in two postcards; one from Frank O’Hara to Ted Berrigan and another from Berrigan to Charles Olson. Much can be made of the micro-lineage threads of the New American poetry and New York School that run through these three poets. Not only are Olson and O’Hara canonical energies within Berrigan’s The Sonnets, but Berrigan’s self-described “rookie of the year” arrival in American poetry occurred at the 1965 Berkeley Poetry Conference, over which Olson’s presence loomed large. Additionally, O’Hara’s work had been a guide for Berrigan on how to live as a young poet. What’s great about the 1962 postcard from O’Hara to Berrigan is that it offers a reversal on the standard hierarchical narratives of literary tradition. Here, it’s O’Hara praising Berrigan’s poems as he invites him out for a drink and “to meet K. [Kenneth] Koch,” who would also be a New York School hero to Berrigan. Evidenced by the tape arranged on the edges of the card to harden and preserve it, Berrigan clearly treasured this correspondence from O’Hara, which due to the use of Berrigan’s full name, seems to have been their very first formal exchange. One images Berrigan, then 27 years old and having just moved to New York City the year before, formally expressing his admiration for O’Hara’s poems in his initial note. This postcard shows Berrigan’s first-hand devotion to his aesthetic sources. On the other hand, the August 16, 1966 postcard from Berrigan to Olson reveals an already well-established and easy going correspondence with the author of The Maximus Poems and “Projective Verse,” as Berrigan, referencing the postcard’s text on the other side, writes, “Dear Charles, We’re about to beat upwind. A loon is crying tonight. Maine is full of sky,” and signs off, “Be seeing you, Ted + Sandy.” Likely having stopped in to see Olson in Gloucester, Massachusetts on the drive up to Maine with his first wife, Sandy, Berrigan is playfully following up with the elder poet only about three weeks after the death of O’Hara.

Among collages and obscenity charges, the New York School material at UConn also runs parallel to and benefits from the archive’s already well-known collections of Frank O’Hara and Charles Olson papers. The resonance of these collections is embodied in two postcards; one from Frank O’Hara to Ted Berrigan and another from Berrigan to Charles Olson. Much can be made of the micro-lineage threads of the New American poetry and New York School that run through these three poets. Not only are Olson and O’Hara canonical energies within Berrigan’s The Sonnets, but Berrigan’s self-described “rookie of the year” arrival in American poetry occurred at the 1965 Berkeley Poetry Conference, over which Olson’s presence loomed large. Additionally, O’Hara’s work had been a guide for Berrigan on how to live as a young poet. What’s great about the 1962 postcard from O’Hara to Berrigan is that it offers a reversal on the standard hierarchical narratives of literary tradition. Here, it’s O’Hara praising Berrigan’s poems as he invites him out for a drink and “to meet K. [Kenneth] Koch,” who would also be a New York School hero to Berrigan. Evidenced by the tape arranged on the edges of the card to harden and preserve it, Berrigan clearly treasured this correspondence from O’Hara, which due to the use of Berrigan’s full name, seems to have been their very first formal exchange. One images Berrigan, then 27 years old and having just moved to New York City the year before, formally expressing his admiration for O’Hara’s poems in his initial note. This postcard shows Berrigan’s first-hand devotion to his aesthetic sources. On the other hand, the August 16, 1966 postcard from Berrigan to Olson reveals an already well-established and easy going correspondence with the author of The Maximus Poems and “Projective Verse,” as Berrigan, referencing the postcard’s text on the other side, writes, “Dear Charles, We’re about to beat upwind. A loon is crying tonight. Maine is full of sky,” and signs off, “Be seeing you, Ted + Sandy.” Likely having stopped in to see Olson in Gloucester, Massachusetts on the drive up to Maine with his first wife, Sandy, Berrigan is playfully following up with the elder poet only about three weeks after the death of O’Hara.  Though Olson himself would die in 1970, and it’s unclear if further correspondence between the two poets exists, Berrigan’s “full of sky” note to Olson again shows his sense of intimacy with the poets whose work he respected and learned from. The archive, as it often does, is showing us how lineage, tradition, and aesthetic exchange are never abstract.

Though Olson himself would die in 1970, and it’s unclear if further correspondence between the two poets exists, Berrigan’s “full of sky” note to Olson again shows his sense of intimacy with the poets whose work he respected and learned from. The archive, as it often does, is showing us how lineage, tradition, and aesthetic exchange are never abstract.

I’m looking forward to returning to the archives at the University of Connecticut to spend more time thinking through the material traces of the poets I love and study, and to continue to utilize these important and still-growing collections to illustrate the ongoing importance and value both of the New York School’s second generation gems and the pedagogical, personal, and scholarly correspondence that archives allow us to develop. “I must be making my own universe / out of discards,” Notley writes in “Waveland (Back in Chicago),” and there’s a sense of that same construction of a world in the loose, wayward ephemera of the archive. What’s most fulfilling is how the process of looking and reading in the archive is always one of presence, and often magically, of being in contact with your sources.

-Nick Sturm

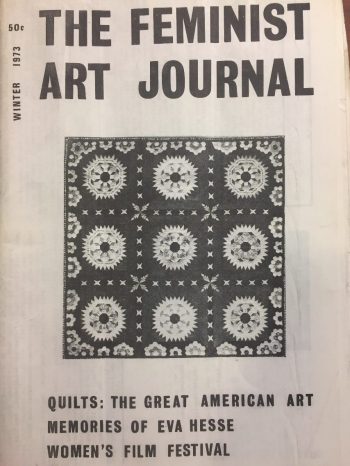

The Search and Struggle for Intersectionality Part II: Other Minorites and the Feminist Movement

Anna Zarra Aldrich is majoring in English, political science and journalism at the University of Connecticut. As a student writing intern, Anna is studying historical feminist publications from the collections of Archives and Special Collections. The following guest post is the final post in the series.

The feminist movement has long struggled with incorporating different groups’ concerns and modes of oppression into the movement. This problem was exacerbated by the multifaceted, turbulent U.S. political atmosphere that characterized the 1960s and 1970s. The differences between black and white women’s views of the movement clashed on several essential dimensions. But the issues of other minority groups were given less attention by the feminist movement, and by society in general, due to the fact that their ethnic/racial factions were much smaller than African Americans’.

Another marginalized group that galvanized in the activist culture of the 1960s and 1970s in America were Native Americans. These men and women sought to have their tribal autonomy recognized. They were also fighting issues such as environmentally harmful mining practices on their resource-rich lands and high rates of substance abuse and poverty within their communities.

Native American women had a unique relationship with the feminist movement because the issues this minority group faced were different from those that white or black women faced, and the ethnic population of which they were a part was a severely marginalized minority. U.S. Census data from 1970 shows that a whopping 98.6 percent of the total population was either white or black/African American (87.5 percent and 11.1 percent respectively). Native Americans constituted less than .004 percent.

Native Americans were fighting for their unique political rights as well as larger environmental concerns during this period.

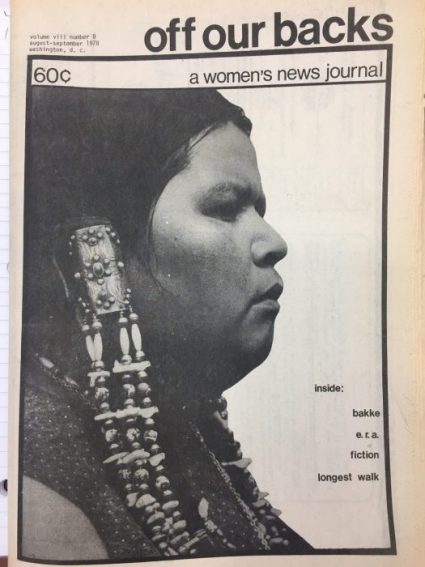

The March 1977 issue of “Off Our Backs” includes an article summarizing the findings of a report by the Association on American Indian Affairs (AAIA), a non-profit organization founded in 1922 to promote the well-being of Native Americans and Alaskan Natives. The report found that Native American children are placed outside of their families at a rate 10 to 20 times higher than that for non-Native American children.

The AAIA argued that this practice deprives Native American children of the ability to be raised with a proper awareness of and appreciation for their culture. This concern emphasizes the fact that Native American women who were involved in the feminist movement during this time were simultaneously combatting the United States government’s systematic efforts to diminish their independence and culture as well as the wide-spread sexism that was the feminist movement’s main concern.

Native American culture celebrates its strong connection to and appreciation of nature. When Native American tribes were forced off their lands in the nineteenth century, they were put on reservations in states like Oklahoma and South Dakota. The U.S. government later came to realize these areas were rich with natural resources such as oil and uranium.

“In the days of diminishing U.S. energy resources, the push is on to take what’s left of Indian land,” according to an article in “Off Our Backs.”

The U.S. government used environmentally hazardous practices to extract these resources, exposing people living on the land to cancer-causing radioactive materials. It also paid the Native Americans working in these hazardous mines very low wages. These practices led to outcry by Native American men and women.

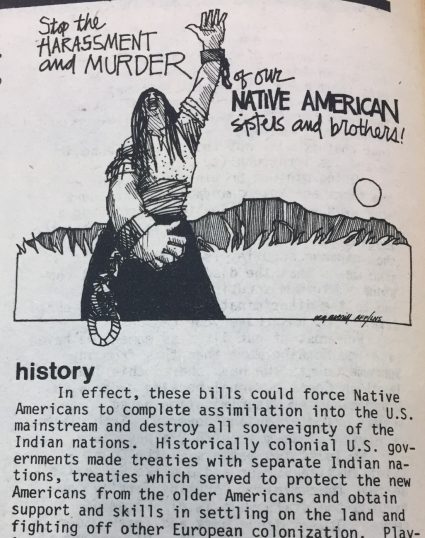

In 1978, thousands of Native Americans participated in The Longest Walk, a protest organized to bring attention to threats to tribal lands pose by several pieces of proposed legislation.

“In effect, these bills could force Native Americans to complete assimilation into the U.S. mainstream and destroy all sovereignty of the Indian nations,” the article on the march said.

In the same August/September 1978 issue that covered the march, “Off Our Backs” included coverage of a conference in New Mexico that addressed the upsurge in domestic violence against Navajo women. This increase was attributed to a “pressure cooker syndrome” created by white culture: “women-battering and child abuse (were) once practically non-existent…and has now reached crises proportions.”

The attempted forced assimilation of native people into white culture created a class system that did not exist in Navajo tribal society. This led to high poverty and unemployment rates which in turn came to be correlated with high rates of substance abuse and domestic violence.

The writers draw attention to the fact that few of the speakers at the conference were from the Navajo or from any other Native American community. Calling attention to the lack of authentic representation at this conference may be an indication of the evolution of “Off Our Backs” in how it dealt with minority issues. When the paper first began in 1970, it struggled to expand their coverage to minority women’s issues, as evidenced by its problematic coverage of a black feminist group’s conference in 1974.

Similar to black women who were involved with groups like the Black Panthers, politically active Native American women were part of efforts led by men. Women of All Red Nations (WARN) was a Native American women’s group that brought attention to issues that affected their community including the displacement of their children, forced sterilization, tribal rights, resource exploitation and racism in the educational system. The group invited several Native American men to speak at a conference it held in South Dakota in 1978 as it did not “believe in the separation of men and women who were working for the same objective.” This serves as a perfect parallel to black women activists who wanted to be a part of the black and feminist movements.

Burning Cloud’s letter serves as a quintessential example of a woman’s struggle to find a way to be politically active as someone with a complex set of oppressed identities.

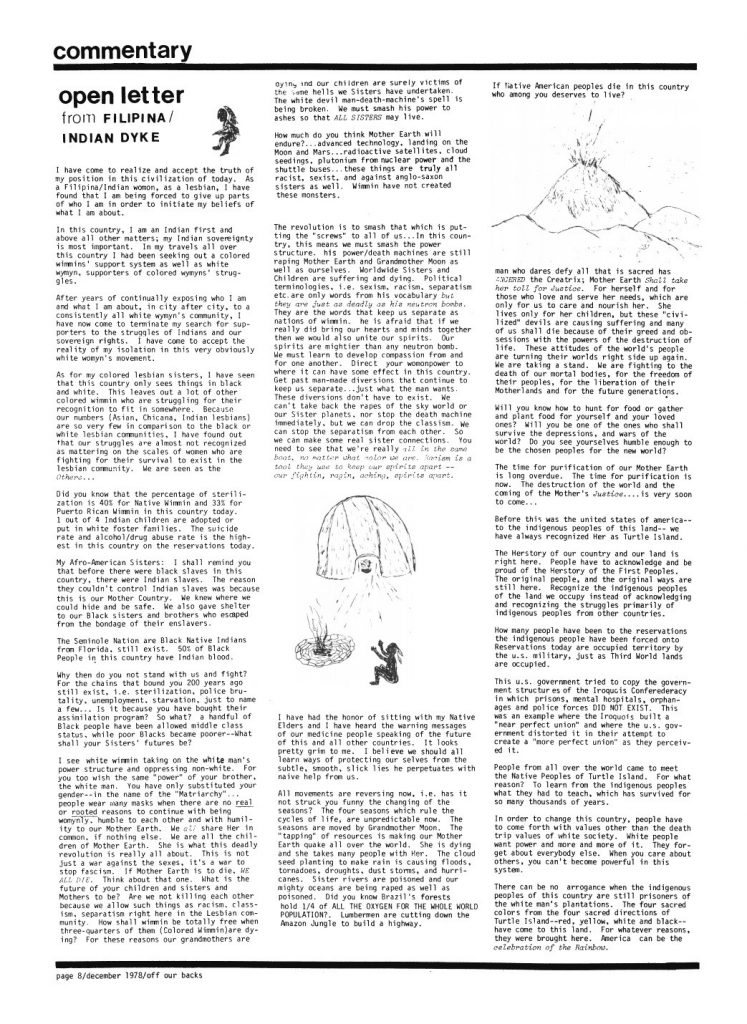

In the December 1978 issue of “Off Our Backs,” the editors printed a letter from Burning Cloud, a self-described “Filipina/Indian Dyke.” In the letter, Burning Cloud shared a sentiment common with those expressed by black women — that she was “Indian first and above all other matters.”

Burning Cloud felt she could not be both an Indian and a gay woman in society. She also expressed frustration with the fact that non-black minorities’ concerns are much more widely disregarded because there are comparatively few of them in number.

Burning Cloud’s letter included a call to action for environmental activism which, from her perspective, was something of which native people were much more conscious due to their spiritual cultural connections to the earth.

“If Mother Earth is to die WE ALL DIE. Think about that one. What is the future of your children and sisters and mothers to be?” she wrote. “Are we not killing each other because we allow such things as racism, classism, separatism right here in the Lesbian community. How shall wimmin be totally free when three-quarters of the (Coloured Wimmin) are dying?”

(Feminists took to using alternative spellings of “women” and “woman” in order to avoid using the masculine root of those words.)

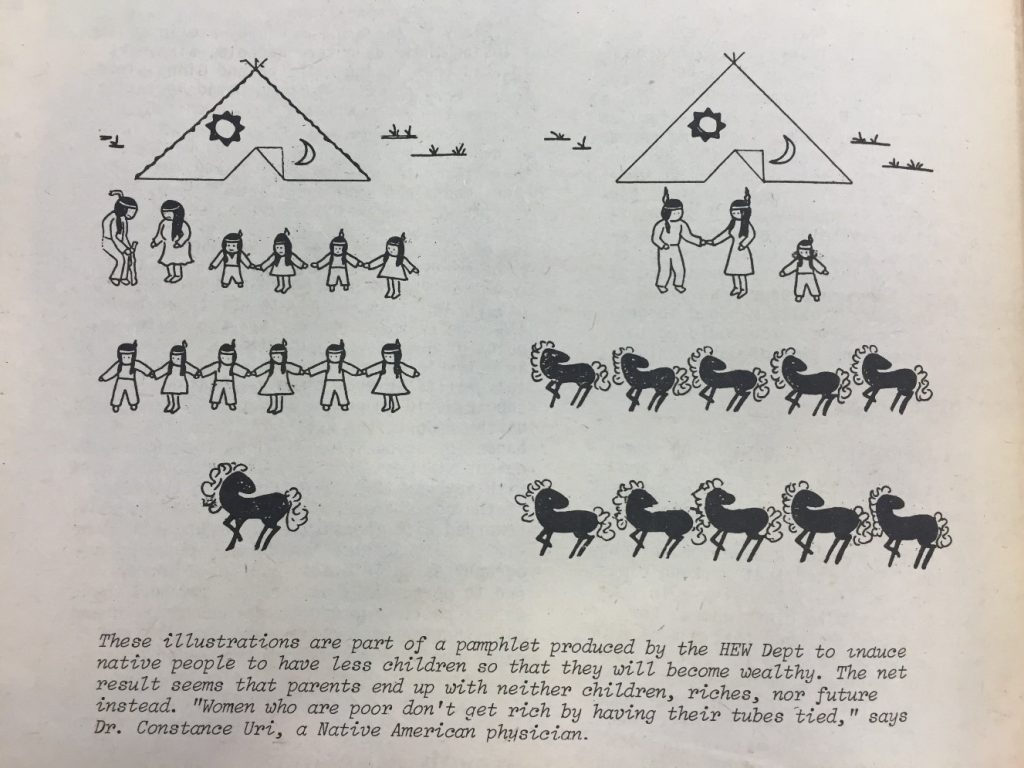

Native American women also faced the issue of forced or coerced sterilization. In “Off Our Backs” article from December 1978, WARN said that 25 percent of Native American Women were forcibly sterilized.

During this period, the United States government instituted polices of population control that targeted minority, underclass women. One third of Puerto Rican woman of reproductive age had been sterilized in 1976. This policy was veiled as a necessary method of population control that would help Puerto Rico develop economically. However, many argued that the problem was not overpopulation, rather that the available resources were concentrated in the upper echelons of society.

In her 1976 University of Connecticut Ph.D. thesis “Population Policy, Social Structure and the Health System in Puerto Rico: The Case of Female Sterilization,” Peta Henderson found that in addition to medical reasons, the law in Puerto Rico regarding female sterilization allowed for women to be sterilized or use other contraceptive methods in cases of poverty or already having multiple children. Henderson found that most sterile Puerto Rican women said they voluntarily chose to have the operation. However, she explores how this choice was corrupted by the fact that government actors worked to persuade these women that sterilization was in their best interest.

The U.S. Government put forth the idea that having fewer children was the surest path to wealth for minority women, ignoring institutional issues including racism and sexism that impeded their social mobility.

These kind of population control polices were also implemented elsewhere in Latin America.

The April 1970 issue of “Off Our Backs,” a female member of the Peace Corps who went to Ecuador said, “Providing safe contraceptives must be a part of a comprehensive health program,” Rachel Cawan said. “Most importantly, however, there must be available other emotionally satisfying alternatives to child raising.”

The prevailing feminist interpretation of these population control programs was that they masqueraded as liberating family planning alternatives when, in fact, many of these women were being coerced or forced to stop having children.

The Young Lords Party was founded in 1960. The men who founded the organization had a series of objectives including self-determination for Puerto Rico, liberation for third-world people and, problematically, “Machismo must be revolutionary and not oppressive.”

Early in the party’s history, the men in the movement did not listen to women’s ideas and concerns during meetings. These women were limited to essentially being glorified secretaries for the party according to a November 11, 1970 New York Times article.

The women in the movement soon tired of this dynamic and demanded to be taken seriously – and they succeeded. Several women were able to assume leadership positions in the party and the pillar relating to machismo was changed to one supporting equality for women. However, this victory did not mean women were automatically able to achieve true political and social equality within the party or on a larger scale.

In a subsequent issue of “Off Our Backs,” a black/Native American woman wrote a response to Burning Cloud’s letter, which had also said black people should support Native Americans’ issues, saying that: “There is a need for Dialogue, a conversation, between Indian people and Black people…We have been divided in order to be conquered, even though for many, our blood flows together.”

A theme that emerges again and again when studying the second-wave of the feminist movement is that by separating women into sects with seemingly irreconcilable differences, men have managed to prevent them from forming a powerful united front capable of combatting not only sexism, but racism and other social ills that afflict them.

-Anna Zarra Aldrich

The Search and Struggle for Intersectionality Part I: Black Women and the Feminist Movement

Anna Zarra Aldrich is majoring in English, political science and journalism at the University of Connecticut. As a student writing intern, Anna is studying historical feminist publications from the collections of Archives and Special Collections. The following guest post is one in a series to be published throughout Spring 2018.

The feminist movement has long struggled with incorporating different groups’ concerns and modes of oppression into the movement. This problem was exacerbated by the multifaceted, turbulent U.S. political atmosphere that characterized the 1960s and 1970s.

“Chrysalis,” a quarterly women’s periodical that was self-published in Los Angeles from 1976-1980, struggled to incorporate African American women’s issues into its editors’ ideals for the movement. In an issue of the magazine that came out in spring of 1979, poet Adrienne Rich wrote an article called “Disloyal to Civilization: Feminism, Racism and Gynophobia.”

“Chrysalis’s” article sharing the story of Annie Mae was a clear attempt to give a black woman a voice in the publication.

Rich’s article emphasized some of the inherent similarities between the struggles of black people and women in America. She wrote that all women and all black people in this country live in fear of violence being committed against them solely due to their gender or race without the hope of justice being served.

Her article went on to explain that dividing women against each other has historically been a means by which men have maintained their oppression: “The polarization of black women in American life is clearly reflected in a historical method which, if it does not dismiss all of us altogether or subsume us vaguely under ‘mankind,’ has kept us in separate volumes or separate essays in the same volume.”

Rich urged women that they “can’t keep skimming the surface” of the women’s movement by refusing to engage with black women’s issues.

“Chrysalis’s” winter 1980 issue featured a story called “I am Annie Mae” which was the story of Annie Mae Hunt, a 70-year old black woman from Texas. Annie Mae’s story was told through a transcript of hours of interviews.

Annie Mae’s story shared the hardships of her life, including her dropping out of school after fifth grade, getting married and having her first child when she was only 15. Annie Mae was pregnant a total of 13 times in her life and had six living children at the time of the article’s publication. Annie Mae said she was never educated about birth control and was told having more children was better for her.

“Birth control – that wasn’t in the makings then. I mean the black people didn’t know it. Poor people like me. There may have been some well-to-do people that knew about it,” Hunt said.

While this article was an earnest effort by “Chrysalis” to tell the story and plights of a woman of color, it was only through a white mouthpiece that Annie Mae was able to share her story; the reporter who conducted and organized the interviews was white as was the staff and, presumably, much of the magazine’s readership. Furthermore, aside from Rich’s essay and this article, examples of “Chrysalis” covering women of color’s issues are sparse.

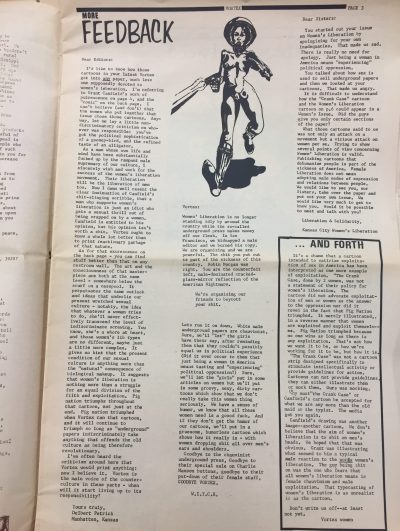

“Off Our Backs,” a bi-weekly newspaper printed in Washington D.C. (1970-2008) did put forth a more valiant effort to communicate the struggles of black women in America through their own voices even if they often fell short of true intersectional understanding.

In the April 15, 1971 issue of “Off Our Backs” an unnamed black woman, identified as someone who held a “high position in the Health, Education and Welfare Department,” was interviewed about her response to the women’s liberation. She pointed out at that at time the women’s movement was predominantly led by and composed of white, middle class women. She said that black women do not want to be a part of what they considered to be a, frankly, racist movement.

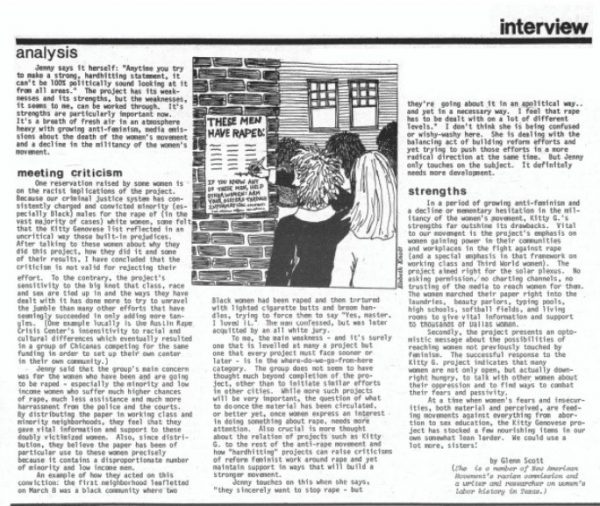

In their article on the Kitty Genovese Women’s Project, “Off Our Backs,” asks directly about this criticism of racial bias.

The 1960s and 70s were a period rife with tension in multiple dimensions, only one of which was the women’s lib movement. This period saw the continuing struggle by African Americans for equality and civil rights. The woman interviewed for the April 15 article emphasized that she, and many other black women, identified as black first and a woman second in terms of their identity and sources of oppression.

In 1977, the Kitty Genovese Women’s Project, named for the woman who was murdered while numerous people who were aware of what was happening did nothing, posted a list of 2,1000 male sex offenders in Dallas County. A group of 30 women handed out over 20,000 copies of the list. Many black feminists took issue with the list as black men were disproportionately represented due to a higher conviction rate among blacks for all crimes due to the racial bias of the criminal justice system.

In 1966, the militant civil rights activist group the Black Panthers formed in in Oakland California. Many black women were involved in the black movement and wanted to work with the men in that movement to achieve their collective goals. Many white feminists, however, argued for a complete break with men.

This argument originated during the first wave of feminism in the United States. Some male abolitionists argued that it was the “Negro’s Hour,” during the last ninetieth century, to quote Wendell Phillips. Men such as Phillips, and Frederick Douglass believed the main focus of the period had to be black men’s rights and that women’s suffrage would have to be pushed to the back burner.

This led women’s suffrage leaders like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony to found the women’s-only National Woman Suffrage Association. This break from the abolition movement may be viewed as a break from black issues in general, which sowed the seeds for the division that reemerged in the next phase of the movement.

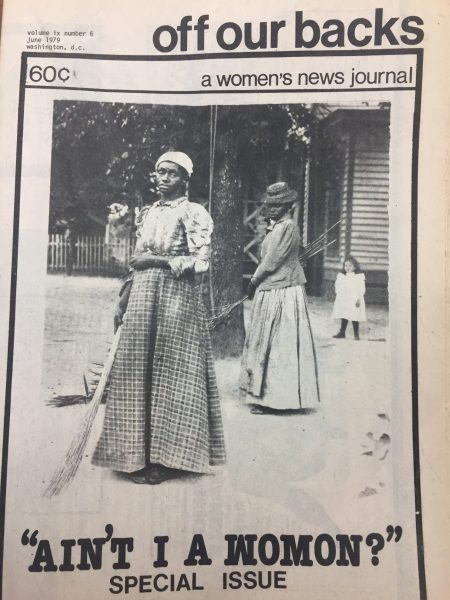

In June 1979, “Off Our Backs” published a special “Ain’t I a Woman” issue, named for a famous speech given by Sojourner Truth at the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. Truth’s speech confronted the stark differences between the treatment of white and black women: “Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman?”

The special issue included a statement from the Combahee River Collective, a black feminist group from Roxbury, Massachusetts. The statement said: “As black women, we see black feminism as the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneous oppression that all women of color face.” They emphasized that, “Black women’s development must be tied to race and class progression for all blacks.”

This special issue was produced by the Ain’t I a Woman Collective, a black feminist organization based in D.C.

The black women and feminists of the period did not believe their plights as black people living in America and as women living in America could be separated. They believed they could not progress as whole humans without both issues, in addition to class, which was often correlated with race, being addressed.

One of the important issues that black women said white feminists did not grasp was welfare. A much larger proportion of black women were in poverty than white women during this period. The U. S. Census (Current Population Survey and Annual Social and Economic Supplements data) from 1975 shows that 27.1 percent of black families were in poverty compared to 9.7 percent of all families. Those statistics become even more staggering when we look at poverty rates for single-female households. 50.1 percent of black families with a single mother were in poverty compared to 32.3 percent of all other single-female households.

Intersectionality hinges on the idea that people have a complex identity that is shaped by a variety of demographic and experiential factors such as race, class and education. Black women were dealing with a variety of issues and sources of oppression during this period that, evidently, many of the white leaders of the feminist movement did not see as falling in line with their goals.

In the winter of 1974, some of the “Off Our Backs” staff attended the first meeting of the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO). The group’s mission was to “fight racism and sexism jointly.” “Off Our Backs'” coverage of the event acknowledged that black women have an ethos to speak about issues that white women are unable to assume: “While ‘Off Our Backs’ has never been vague about its commitment to cover the issues and to carry messages about them to feminists, only a group like NBFO deeply immersed in the survival struggles of low-income black sisters and their own experiences, can be a valid messenger and a forceful mover of these issues.”

The coverage of the event emphasized that racism has kept women systemically divided by making minority women feel they could either be black or a feminist. Unfortunately, the article is critical of the fact that that many speakers ranked racism over sexism in terms of which was a more pressing issue. This clearly displays that many white feminists could not grasp the fact that these women felt they needed to confront the systemic racism in the country in tandem with, and perhaps, some would argue, before, sexism.

The “Off Our Backs” article said that black men did not want black women to join the feminist movement and point out that male-dominated black media outlets like “Jet” or “Ebony” did not attend the meeting when many white feminist presses did. The writers also criticized black feminists for not utilizing these feminist outlets. This provides an interesting area to use to examine the underlying issues here – black women’s issues were not covered well by most white-dominated feminist media outlets, yet the writers of “Off Our Backs” suggest that these women were not reaching out to allow their stories to be told by these papers.

It is necessary to mention that there is a conspicuous lack of exclusively black feminist publications in Archives and Special Collections’ holdings at the Dodd Center. This may be attributable to gaps in the collection or there may have been few publications that served this specific interest group. It seems that black women’s issues were split between the feminist and black movements with some overlap in the media for each.

-Anna Zarra Aldrich

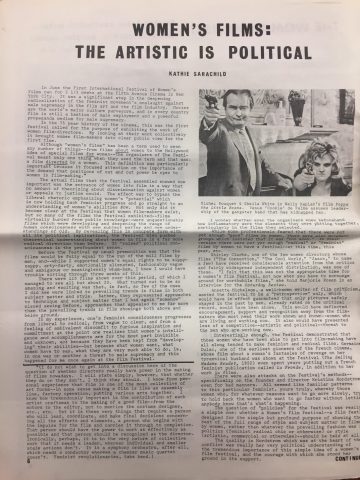

I smell a RAT

Anna Zarra Aldrich is majoring in English, political science and journalism at the University of Connecticut. Anna is a student writing intern studying historical feminist publications from the collections of Archives and Special Collections. The following guest post is one in a series to be published throughout the Spring 2018 semester.

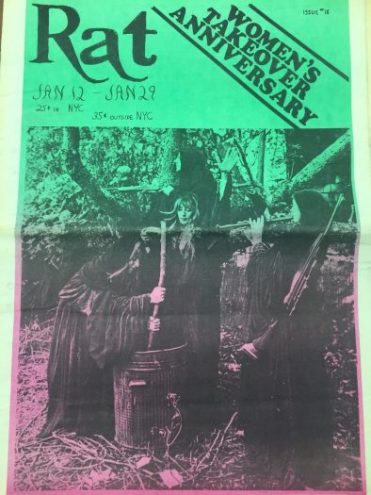

In February of 1970 a terrorist group took over a prominent underground newspaper in New York.

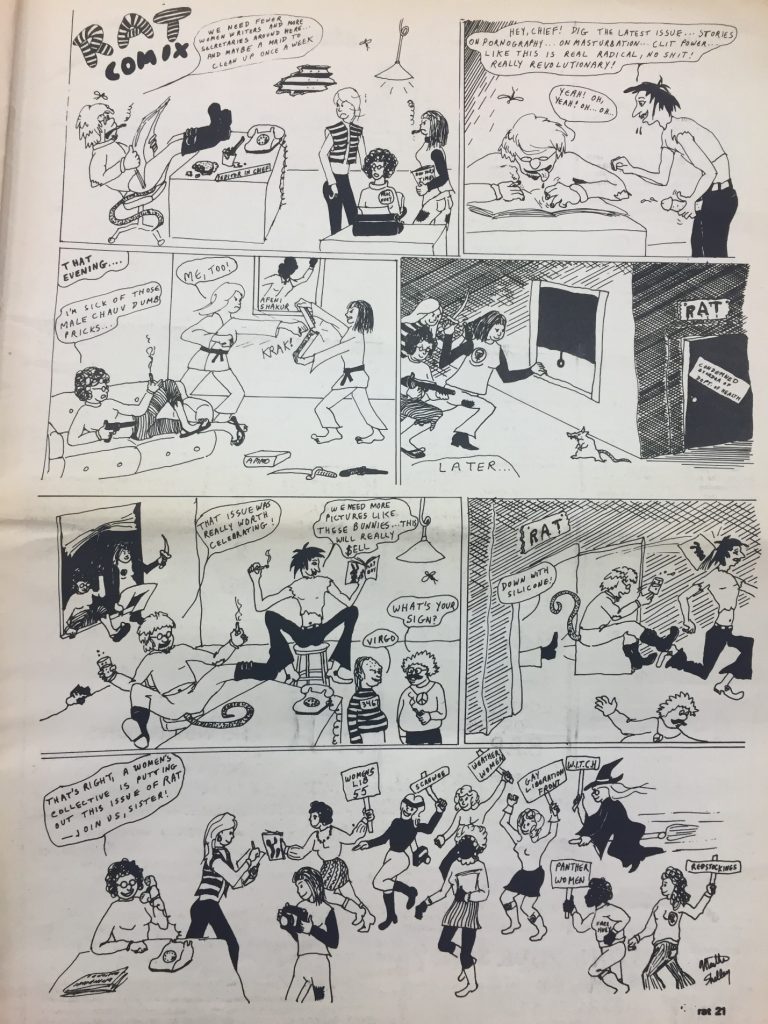

The Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell (W.I.T.C.H.), a direct-action political group, along with several other women’s groups and female “RAT” staffers took over the newspaper for what was supposed to be a single, token issue of the paper. The headline on this issue read, “Women Seize RAT! Sabotage Tales!”

This comic, published in the women’s issue of RAT illustrates the takeover which was enabled by numerous women’s groups including W.I.T.C.H.

The women’s issue featured an essay by Robin Morgan, an American writer and noted feminist activist, titled “Goodbye to All That.” The essay sharply criticizes the advertisements using photos of women that bordered on pornographic and the continual exclusion of a feminist viewpoint from the paper.

“We have met the enemy and he’s our friend. And dangerous,” Morgan wrote.

Morgan’s article rallied against the white, male domination of the radical anti-war/anti-establishment movement. She said, “Goodbye, goodbye. To hell with the simplistic notion that automatic freedom for women – or nonwhite peoples – will come about zap! with the advent of a socialist revolution. Bullshit.”

Grievances against male radicals were common among feminist writers during this period. A pamphlet written by Andrea Dworkin in 1973 titled “Marx and Gandhi Were Liberals” stated that men permitted women to take part in their vision of the revolution so long as they kept their own demands moderated and subsumed within the male-dominated agenda.

“Liberal gestures of good will are made when we are shrill enough or when we are fashionable enough as long as we do not interfere with the ‘real revolution.’ Increasingly we understood that we are the real revolution,” Dworkin wrote.

The January 25-February 9, 1970 issue of “RAT,” the last one published by the male editorial staff, included numerous articles on pornography and masturbation. An article by Uncle Leon Gussow argued that pornography gives young men unrealistic views of sex and creates a separation between him and the act of sex. The women who worked at “RAT” took issue with how this topic was approached by the male staff; they believed this article, and the paper in general for quite some time, promoted pornography. Many women saw pornography as problematic as it often portrayed violence against women and this became a major issue in the women’s liberation movement.

The women also disliked the fact that the tongue-in-cheek titles that appeared on the masthead of each issue were often demeaning and stereotypical to women, referring to them as “princess” or “muffin purchaser.”

After the women of “RAT” published their issue they were loath to return control to the men who had been running the paper since its inception in 1968. So they didn’t.

In the next issue, the women still made up the entirety of the editorial staff, but some men came back temporarily as production staffers to ease the transition. In a letter to the readers, the editors said they were trying to “work it out” with the men. All male staff members were eventually asked to leave the paper and control remained in exclusively female hands.

A letter to the readers from former editor Paul Simon explained that after a “stormy” meeting between the men and women of the paper, it was decided that the paper would continue to be published by the women.

The takeover at “RAT” inspired women working at other papers across the country to follow suit. In the April 4, 1970 issue of “Vortex,” an underground paper published out of Lawrence, Kansas, W.I.T.C.H. wrote a letter to the paper saying, “you are a counterfeit left male-dominated cracked-glass-mirror reflection of the American nightmare.” The letter said the group was preparing to organize a boycott of the paper.

This letter was published in the issue of the paper following issue on the women’s liberation similar to the one that initiated the permanent takeover of “RAT.” In September of that same year, “Vortex” moved to a collective model of publication. This altered the existing editorial structure at the paper and gave women a larger say in its production beyond their single issue which, unfortunately is not available at the Dodd Center Archives.

“RAT” continued its coverage of issues like the Vietnam War and the trial of the 21 members of the Black Panther Party who were charged with coordinating attacks on a series of New York City buildings. However, the new editors made sure to make women’s issues and the accomplishments of female activists more prominent.

They featured letters from Mary Moylan, one of the Cantonsville Nine, a group of activists who burned draft files to protest the war. Moylan went underground, hiding from the authorities for a period and her letters about her time underground were published in “RAT” and other publications like the women-run “Off Our Backs.” “RAT” also featured articles about women’s role in the Israeli-Palestine conflict.

In March of 1971, the paper changed its name to the Women’s LibeRATion.

One thing the women sought to dissemble with their takeover was the hierarchical structure that had allowed men to squelch their voices for so long. This led them to establish a newsroom that was much more free-flowing and less rigidly structured. In a letter to the readers, the editors describe the RAT work collective’s meetings as “un-chaired and chaotic.”

The paper continued publishing with relative consistency through 1972 and then stopped abruptly for several months. Then, in April of that year, a newsletter came out.

The single printed sheet explained to readers that the fate of “RAT” was in limbo due to internal fractionalization. A group of six black gay women had seized control of the paper after airing their grievances against the white feminist viewpoint that had been almost exclusively featured by the paper.

The black women writing the article said there were too many fundamental misunderstandings between the white and third-world women in the movement to be reconciled into a cohesive vision in which all voices could be heard.

The letter published on the back cover of the single-sheet issue asked readers to respond with feedback and monetary donations to support the continuation of the publication

The newsletter closed with a request for feedback from readers, “Your responses will determine the outcome of the almost defunded ‘RAT;”. The paper also asked for monetary donations to help keep the presses running.

Unfortunately, it appears these women were unable to keep the paper afloat either due to a lack of interest or lack of funds.

The downfall of “RAT” showcases the lack of an understanding of the idea of intersectional feminism during this time. Perhaps it also demonstrates a lack of will on the part of white feminists to create connections with minority women and engage in meaningful dialogue to understand their issues. Minority voices were not generally included in the more-prominent feminist outlets, or if they were given a space, it was still through the good graces of white editorial staffs. This is an unfortunate truth that the feminist movement continues to grapple with today.

-Anna Zarra Aldrich

Aphradisiac

Anna Zarra Aldrich is majoring in English, political science and journalism at the University of Connecticut. She is a student writing intern studying historical feminist publications from the collections of Archives and Special Collections. The following guest post is one in a series to be published throughout the Spring 2018 semester.

During the 1960s and 1970s feminist writers established themselves with a distinct and demanding voice. In order to accomplish the feat of integrating a prominent female presence into the literary world, women created and utilized exclusively female publishing mediums. Women took to using alternative methods that allowed them to cultivate this unique literary culture outside the realm of the traditionally male-dominated publishing world.

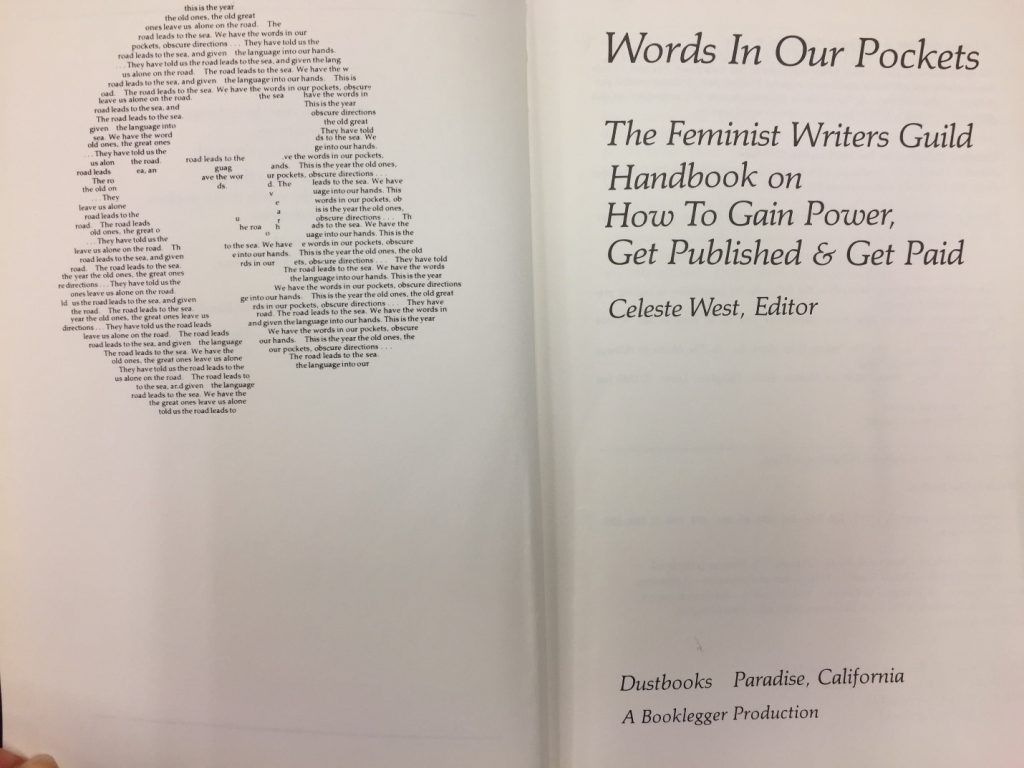

In 1985, noted librarian and author Celeste West published a book titled “Words in Our Pockets: The Feminist Writers’ Guild handbook on how to gain power, get published & get paid.” The book provided an in-depth look at the publishing world through a feminist lens and provided women with resources and options for alternative paths to publication.

In 1985, noted librarian and author Celeste West published a book titled “Words in Our Pockets: The Feminist Writers’ Guild handbook on how to gain power, get published & get paid.” The book provided an in-depth look at the publishing world through a feminist lens and provided women with resources and options for alternative paths to publication.

The cover of the book depicts a woman’s portrait composed of the words of a poem by Denise Levertov’s from which the book gets its title. It reads: “But for us the road/ unfurls itself, we count the/words in our pockets.”

The introduction of the book states that, “The present wave of feminism is…creating a women’s cultural renaissance, the first since matrifocal times. At last, we are building, in large numbers, our own literary tradition, finding our own audience, and from these, shaping a world view.”

This book emphasizes the fact that many of the most influential members of the movement have been writers who use the power of the written word to express the urgency and necessity of the changes they demanded.

West’s book begs the question: “Who among us can afford silence?” West wanted to encourage women to make their voices heard through the literary mire that was oversaturated with male perspectives.

The book goes through a basic how to process for practical elements of publication including writing proposals, making sense of the legal jargon in contracts and financing options. The book also deals with the sexism of the industry. The book provides advice on how to deal with people, namely powerful men, who refuse to take women writers seriously and list feminist publishers and a guide on self-publishing as a means to circumvent discouraging male publishers.

“You are a writer, not a wallflower. Why wait for some gentleman publisher to sweep you into his arms and carry you off to the Big House?” West proposes.

In an article published in the summer 1979 issue of “Chrysalis” magazine, West wrote “Book publishing, like all industries, is controlled by rich, white, heterosexual men. To retain this power, their books naturally reinstate status quo attitudes of privilege and discrimination.”

The article cites the figure that 70 percent of books published were produced by 3.3 percent of the over 6000 publishing houses that existed at the time. West calls independent, alternative press outlets “the slice of tomorrow.”

The book’s engagement with the challenges female writers faced showed that even as women encouraged each other to write, the established system often operated to keep them excluded. This created a space for female-run literary publications that provided a platform for women writers who were not welcomed into traditional literary circles.

“Aphra” was an feminist literary magazine published quarterly from 1969 to 1976 out of New York City. The magazine got its namesake from the pioneering English poet, playwright and author Aphra Behn (1640-1689) who was the first woman known to have earned her living by writing.

“Aphra’s” mission statement was “Free women thinking, doing, being.” In the preamble to their first edition, the editors state that the purpose of the magazine is to provide women with an outlet to express themselves: “We submit that one reason for the form of the current upsurge in feminism…is that the mass media provides such biased and commercially oriented material. The literary and entertainment scene are dominated by male stereotypes, male fantasies, male wish fulfillment, a male power structure,” echoing West’s complaints.