Blog entry #3 – Meet William Gray

Looking through more than twenty boxes of the James Marshall Collection has made me feel close to this man I will never have the good fortune to meet. Marshall published about eighty books, many with both his illustrations and text. It is hard to imagine how much he would have produced if he had not died at the early age of 50. In fact, many days I have left the Dodd Center feeling a great sense of loss at his death. Through a friend, I was able to meet Marshall’s longtime partner, William Gray. I met William at the home he and James shared for much of Marshall’s career. For my final blog entry, I’ve included a few of William’s answers to the questions he generously and kindly provided. My thanks go out to William Gray for sharing his time and memories of James Marshall.

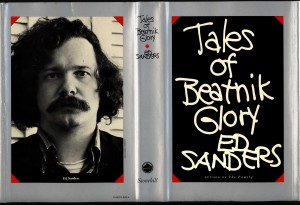

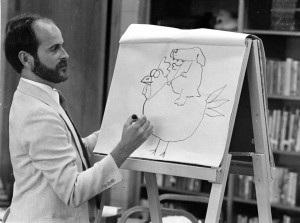

James Marshall giving a presentation (James Marshall Papers Collection File photograph, n.d.). All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

As I mentioned in my first blog, James Marshall wrote many of his books under the pseudonym Edward Marshall. William explained that Marshall wanted to work with more than one publisher. In order to not compete with his own picture books, the pseudonym was used and he wrote in a different genre, beginning readers. “They really suited his talent. I wouldn’t say they were easy to do just because they were easy to read. It was something that just came more naturally to him, the smaller format.”

To clarify that the comments in the margins of the dummies and manuscripts are Marshall’s, I asked about the handwriting and if William knew if anyone else wrote comments on Marshall’s work. William replied that, “He [Marshall] used a Schaefer fountain pen with those plastic capsules to draw with and to write with. He had pretty distinctive handwriting, but no one came near his work.”

I went on to ask specifically about the Harry Allard and Jeffery Allen manuscripts I discussed in my second blog post. William told me that Allard and Allen were both friends of Marshall before each collaborated on books with him. “They would mail a manuscript to him [Marshall]. He would tear it apart limb from limb and then put it back together according to what he thought was best.”

I noted that almost all of Marshall’s changes went to print and William agreed,“Oh, they made every change he suggested. He ran the show….Jim appreciated their inventiveness. I mean Harry came up with The Stupids and with Miss Nelson. But as for shaping a story, that was always Jim’s work.”

William and I talked about Marshall’s ability to critique his own work. “Jim was extremely critical of his own work and any work,” William told me. “Nothing was perfect. Even if it was a masterpiece he would find something to criticize, always. He would very seldom say, ‘I guess this is pretty good.’ He had critical faculties that kicked in and that is what kept him going.”

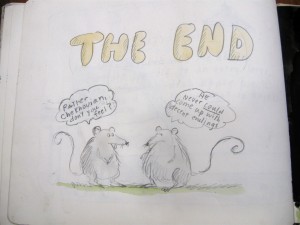

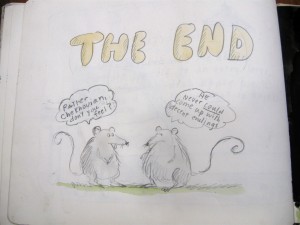

This comment came back to me when I went through Maurice Sendak’s bequest of additional James Marshall material. Sendak and Marshall were good friends, and Sendak owned several of Marshall’s book dummies and original artwork, most of which are now with the Marshall Collection. Among these Sendak materials is a book that Marshall created for Sendak’s birthday. The book is extraordinary, with wonderful characters wishing Maurice a happy birthday. Marshall also includes a short story from his future publication Rats on the Roof. At the end of the story, Marshall is once again critical of his endings, drawing two rats with speech bubbles. The first rat says, “Rather Chekhovian, don’t you feel?” The second rat replies, “He never could come up with decent endings.”

A page from the Birthday Book for Maurice Sendak from James Marshall (Maurice Sendak Collection of James Marshall Box 2012.0152.2). All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

I asked William if there was a work that Marshall was most proud of or that achieved what Marshall wanted? William replied, “I can tell you I really, really appreciate the Fox books. I think his talent went into that in a way that really expressed himself and certainly delights me.” William went on to say that Marshall “was kind of stuck in the George and Martha books pretty much in the framework of a relation between two people, but with the Fox books there would be all kinds of plots and subplots. None of those characters is two dimensional. In just a few sentence you know exactly who they are. I even have people say, ‘Oh, well obviously he used me for Carmen.’”

This led me to ask if Marshall was most like Fox. William said, “I think so… There is a lot of Jim in Fox.” William and I continued on to discuss the brilliant endings and humor in the Fox stories, and the way the humor was not spelled out. William said that was intentional. In fact, it was“his [Marshall’s] number one rule. Never condescend to children. Don’t do it ever.”

Most of Marshall’s sketchbooks and drafts are marked with a place and date. It became clear that he worked constantly, even while traveling. There are often to-do lists in the midst of his sketches. In one list from a trip to Cape Cod on March 10, Marshall is “working on a dummy for Yummers II, driving to Boston, going to lunch, meeting with someone from Houghton Mifflin, doing something at Nickelodeon, driving back to the Cape, picking up lamb shanks, and working in bed on Roberta Molesworthy (an iffy book).”

A page from Marshall’s sketches. (James Marshall Papers. Box 8:Folder 170). All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

The year isn’t dated, but Yummers Too was published in 1986. If Marshall was working on a dummy for this book, I can guess the date would be around 1984. Williams said that Marshall always worked. “Everything was integrated into his work.” He didn’t like to fly and preferred to work on trains. “He’d take a train to Texas or California. He loved to work on the train.”

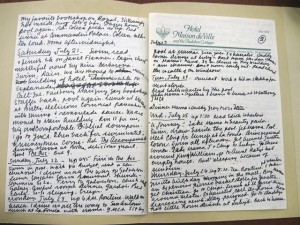

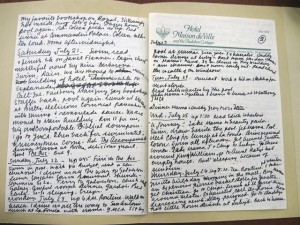

In addition to sketchbooks, William said Marshall also kept extensive diaries. William has kept these diaries, but I did find one trip diary in the collection. The year isn’t dated, however, I can guess from what he was working on that it is probably from around 1990. The diary is all text and details his trip to New Orleans, including what he read each day: “finished a book on Janet Flanner…masterful novel by Nina Berberova, The Accompanist… Editon Wharton.”

A page from Marshall’s trip diary to New Orleans. (James Marshall Papers. Box 21:Folder 299). All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

Marshall was also a voracious reader. William showed me the special shelves Marshall had built around his room to hold some of his books.

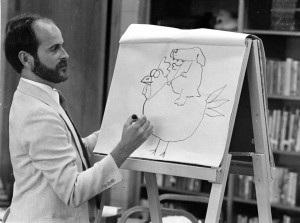

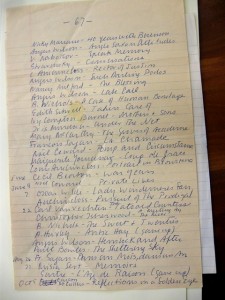

A list of books from the Marshall Collection. (James Marshall Papers. Box 21:folder 303). All rights reserved. No reproduction of any kind allowed.

William said he liked “Moliere and Chekhov…and a lot of the British women novelists like Elizabeth Taylor and Jean Rhys.” I found a piece of paper with a list of books in the collection. I am assuming these were books Marshall had read or books he purchased to read.

The page was numbered 67.

I’ve learned much in going through the Marshall papers and in talking with William Gray. James Marshall was incredibly talented in his ability to do both quality text and illustrations. He worked very hard to achieve the high quality. Going forward, it will be impossible for me to view my own work without giving it a more critical look: What would James Marshall say? He would most likely say “it could be better” and he would probably be right. Achieving the highest quality takes not only talent, but the sweat, tears, and labor of hard work. On that note, with all that I have gleaned from seeing Marshall’s process, it is time that I get back to the hard work of improving my own manuscripts. Thank you James Marshall, and thank you to the Dodd Research Center and the providers of the James Marshall Fellowship.