The UConn Archives & Special Collections podcast d’Archive will release it’s 50th episode on April 24th, 2023 with a live broadcast at 10am EST on 91.7fm WHUS. Beginning in August of 2017, the Archives staff began expanding its outreach program to the airwaves by training on sound engineering and radio protocols in order to effectively bring its collections to new audiences. Since then the radio program and podcast has featured weekly episodes drawing from countless collections held by the Archives & Special Collections and amplifying the expertise of over 60 collaborators ranging from past and present archives and library staff, artists, journalists, curators, faculty, graduate and undergraduate students, high school students, visiting fellows and international students, activists, alumni, collectors and donors, family, and friends.

Continue readingTag Archives: Alternative Press Collection

Activism at the High School Level

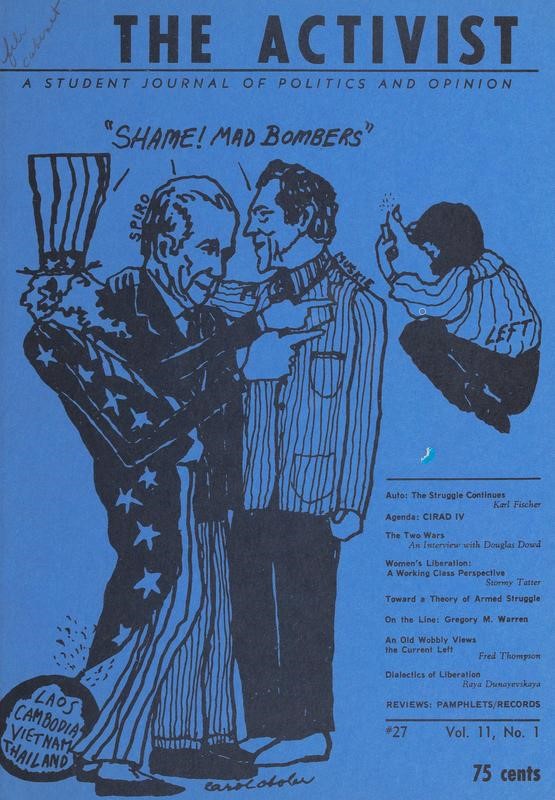

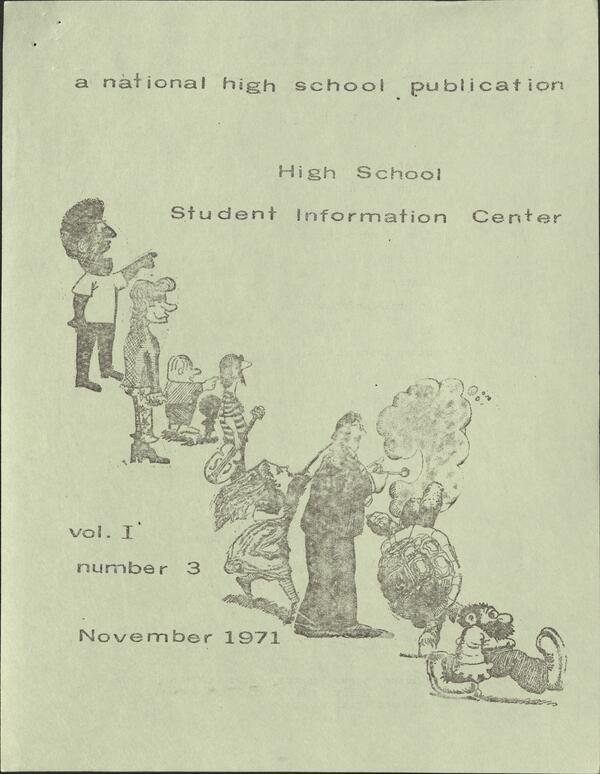

Over the past six months, I have had the privilege of working to digitize the Alternative Press Collection (APC) here at the University of Connecticut Archives and Special Collections. While the APC contains publications created by all kinds of people that discuss all kinds of topics, a large portion of the collection focuses on activist movements during the 1960’s and 1970’s. I began working to digitize files from the APC after I graduated from UConn and have thus looked at a lot of different materials dealing with many different forms of activism.

When studying the history of activism in the United States, a lot of sources will focus on the groups and movements that were either created by or largely consisted of young adults, particularly those in college. This is hardly surprising, given that college communities are most often structured in a way that encourages students to spend substantial amounts of time together and discuss current events, which often leads to like-minded individuals coming together over specific topics. College students also have easier access to resources such as printing which makes spreading awareness easier than it otherwise would be. When all these things are put together, they create a recipe for large activist groups that can leave behind tangible evidence of their activities and their beliefs.

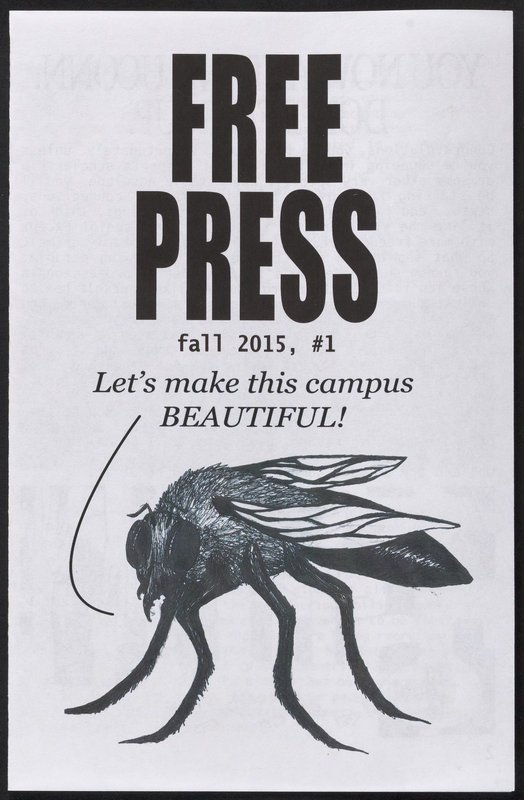

One branch of activism that is less frequently discussed, however, is high school activism. This is, again, not unexpected. High school students have access to fewer resources than their college-level counterparts and are often subject to more restrictions around where and when they’re able to assemble. But teenagers across the country have always been a part of activist movements. Within the Alternative Press Collection here at the UConn Archives and Special Collections, there are several different publications created by High School activists who had hoped to give students access to points of view other than what they might get from their parents and teachers, and to spread awareness of movements and events that they might not otherwise hear about.

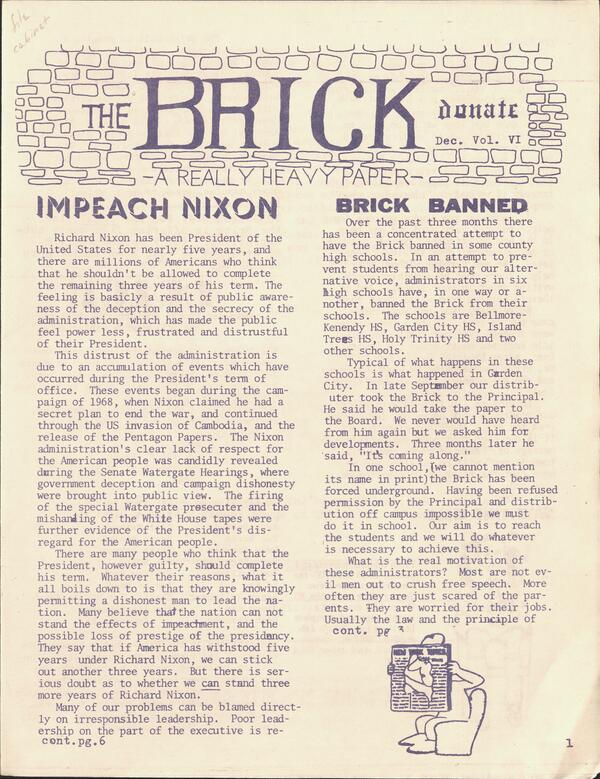

The different publications come from across the country and cover topics ranging from nationwide movements all the way down to local issues, from an investigation into the legal rights of American high school students to a discussion about an income tax versus a sales tax in Windsor, Connecticut. Some of these publications also claim that the administration at their schools have explicitly forbidden them from writing and publishing these articles, yet they have decided to do so anyway, despite the possible consequences. In an issue of ‘The Brick; A Really Heavy Paper,’ for example, an anonymous contributor describes the pushback this publication received from school boards and administrators in various schools in Nassau County, New York.

“In one school, (we cannot mention its name in print) the Brick has been forced underground. Having been refused permission by the principal and distribution off campus is impossible we must do it in school. Our aim is to reach the students and we will do whatever is necessary to achieve this.”

Publications like The Brick serve as important reminders that activism has no age limit. To see more examples of High School activist publications, follow this link to the Alternative Press Collection High School Publications folder.

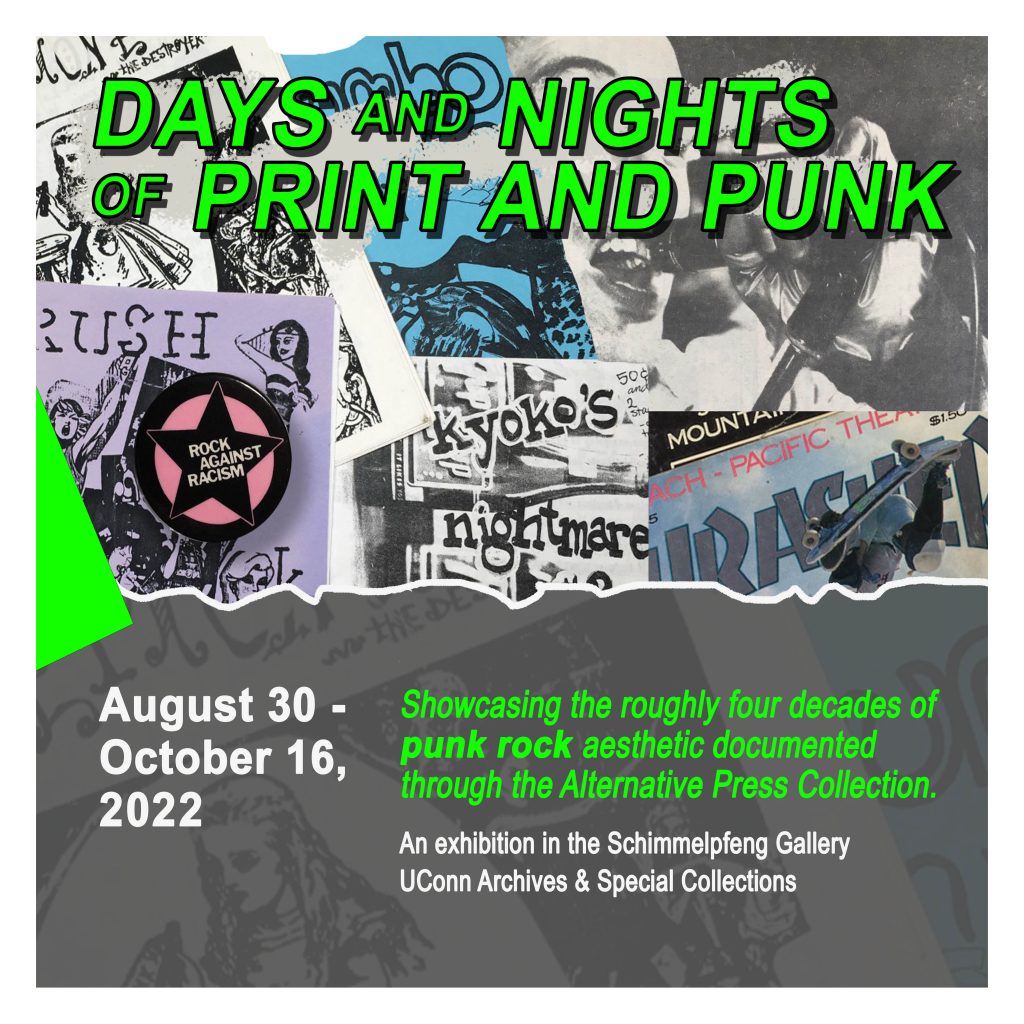

Days and Nights of Print and Punk

Exhibition on view August 30 – October 16, 2022

Monday through Friday, 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m

Schimmelpfeng Gallery, UConn Archives & Special Collections

Virtual Zine Workshop September 29, 12:30-1:30pm

Closing Event & Archives Open House October 12th, 4 – 6 pm.

The UConn Archives & Special Collections presents Days and Nights of Print and Punk, showcasing the roughly four decades of punk rock aesthetic documented through the Alternative Press Collection. From the 1970s punk rock of bad attitudes and discontent in England and the U.S., seeds were sown to propagate a unified front of thumbed noses to the status quo. Those same attitudes of youth rebellion were reinterpreted from problems into solutions by each successive generation drawing from positive mental attitude, feminism, DIY socioeconomics, animal rights, and anti-racism. Through show flyers, riot grrrl and skate zines, t-shirts, stickers, vinyl, cassettes, and posters, the evolution of the scene has demonstrated its adaptability for youth movements from the late 1970s to the present day. This exhibition also features selections of performance photographs from the traveling exhibition Live at The Anthrax from the Joe Snow Punk Rock Collection. Joe photographed the thriving Connecticut Hardcore Punk (CTHC) scene in the late 1980s during the final years of The Anthrax club in Norwalk, CT (’86-’90). Shot on 35mm black and white Kodak film, these images represent historical documents that bring the viewer as close to the action as possible, providing an intimacy into this subcultural space from 35 years ago. The photographs were selected and reprinted with the intent to highlight the primacy of analog at that time as well as the aesthetics of the not-so-distant past illuminated by a sweat tinted flash bulb.

This exhibition is drawn from the following archival collections:

Andrews Punk Rock Collection, Fly Zine Collection, Kauffman Zine Collection, King Alternative Press Collection, Noelke-Olson Button Collection, and Snow Punk Rock Collection.

This exhibition is programmed in conjunction with the William Benton Museum of Art exhibition Wild Youth: Punk and New Wave from the 1970s and 1980s running concurrently.

D-I-Y Zine Basics September 29, 12:30-1:30pm via Zoom

Zines are DIY publications that have served as modes of expression as well as communication for underrepresented subcultures and social movements, including punk. They are analog and use a collage aesthetic to combine image and text in visually engaging ways. In this virtual workshop, learn about DIY publications with Archivist Graham Stinnett and Metadata Librarian Rhonda Kauffman to get started making your own zines. Held in conjunction with the exhibitions, Days and Nights of Print and Punk at UConn Archives’ Schimmelpfeng Gallery and Wild Youth: Punk and New Wave from the 1970s and 1980s at the William Benton Museum of Art.

Suggested materials list: • 1 sheet of letter sized paper • Magazines, newspapers, stickers to collage with, preferably images with high contrast. • Glue stick or tape • Sharpie fine and ultra fine permanent markers • 1-inch and ¾ inch alphabet stickers in various colors • Patterned Washi tape

Level Up materials list: • Label maker • Plastic bone folder • Alphabet stamps w/ink pad • Long arm stapler • Typewriter • Photocopier

Human Rights Internship Report with Aidan Brueckner

This guest blog post is written by Aidan Brueckner, a graduating honors student majoring in Digital Media and Design, and minoring in Human Rights which he completed an internship for at the Archives & Special Collections in the Spring Semester of 2021. Aidan’s descriptive work can be found in the Alternative Press Collection online.

It is no secret that youth activism is on the rise. Across the world, demonstrations

occur for myriad reasons related to racial justice, climate change, drug control, and

countless more key issues. Not only are these matters far-reaching across all aspects of

society, touching on numerous disparate sectors, but the apparent frequency of social

justice events is increasing quickly as well. The push for recognition and change from a

world that has proven unforgiving and unfair is picking up steam. Naturally, college-age

students tend to be a large portion of the ones driving these agendas, as the nature of

college itself encourages collaboration and a drive to excel, as well as an increased

emphasis on critical thinking. Most importantly, however, college allows students to

collect as a group of like-minded individuals, and presents them with an opportunity to

make their voices heard. UConn is no exception, having had a well-documented history

of activism on campus from its inception. Much of this activism is contained within the

Archives, and this semester I had an opportunity to explore and evaluate some of it.

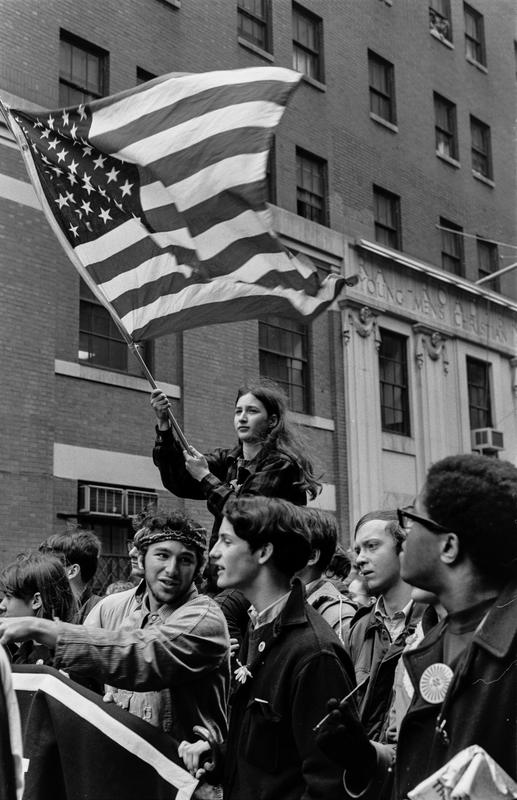

Student Unrest Photography in 4D

New York Peace March, April 15, 1967

In the Spring semester of 2020, an exciting use of historical photographs by UConn Digital Media and Design students brought to life the images of student protest in the 1960s and 1970s held by the University of Connecticut Archives. In collaboration with Assistant Professor Anna Lindemann and MFA graduate Instructor Jasmine Rajavadee of the Digital Media and Design Department, the Motion Graphics 1 class (DMD 2200) spent a portion of their semester in the archives to understand the context of photographic collections and practice their skills on digital collection items. This exploration led to the creation of new uses for the recorded past. The class assignment drew on digitized 35mm negatives, Kodachrome color slides, and black&white photographic prints to demonstrate a 4D animation process of still images to bring static subjects to life. Collections utilized for this project ranged from the Cal Robertson Collection of anti-nuclear demonstrations in New London, Howard S. Goldbaum’s Photography for the Daily Campus newspaper documenting anti-Vietnam War demonstrations in Storrs, New York, and Washington D.C., and University of Connecticut Photography Collection images of the 1974 Black Student sit-in at Wilbur Cross Library. To view a selection of the Student Unrest Photography in 4D project, follow this link to our Youtube page.

This project was a timely and innovative use of a subject matter that was re-energized through Storrs campus demonstrations around racism, global climate change and mental health advocacy throughout the 2019-2020 academic year. In addition, UConn Archives exhibitions Day-Glo & Napalm: UConn from 1967-1971 on student life and activism of the Vietnam War Era and UConn Through the Viewfinder: Connecticut Daily Campus Photographs from the Howard Goldbaum Collection at the William Benton Museum of Art reminded the community of it’s involvement during times of national change.

This is the second time that the UConn Archives has worked with Prof. Lindemann and the DMD department to utilize photographic collections for class projects, the first drew on child labor images from the U. Roberto Romano Collection which can be viewed here.

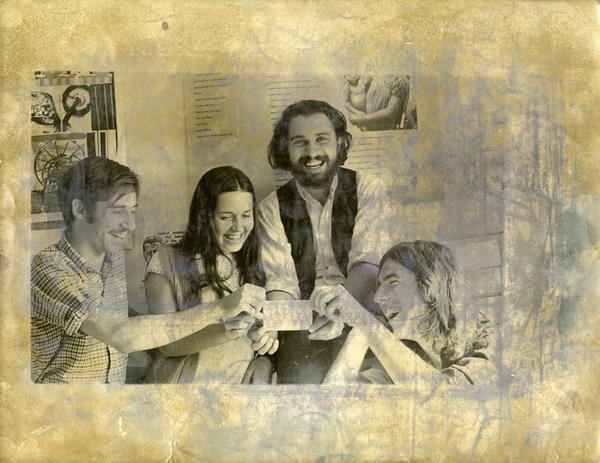

Anarchism at UCONN (Believe It or Not!); The Inner College Experiment

This guest post by Prof. Len Krimerman is in conjunction with the current exhibition Day-Glo & Napalm: UConn 1967-1971, an exhibition guest curated by alumnus George Jacobi (Class of ’71) on the student times of the late 1960s and early 1970s at UConn and in recognition of the 50th anniversary of the Woodstock Music Festival of 1969. Currently on display until October 25th, 2019.

By Len Krimerman*

BEFORE THE BEGINNING

“Anarchism at UCONN” may seem a baffling title or an attempt at dry humor. We are, after all, not talking about the ‘60s and ‘70s at UC Berkeley or Ann Arbor’s University of Michigan. And today our own state’s flagship university is safely and securely nestled within what its region delights in calling itself – “the quiet corner”.

But I can assure you, there really were years, not days or months, when anarchy, or something very much akin to it, had a place within and was tolerated by UCONN. Though there is now no tangible trace of this anarchic educational venture, and no documentation of it in the official histories of this University, it actually did emerge, and it had a great run.

So let me tell a bit of this radical experiment’s story. The idea of it came to life in an undergraduate course in social and political philosophy I was teaching in the Fall of 1968. We were discussing social critic Paul Goodman’s The Community of Scholars, which certainly sounds tame enough. But his book’s challenging anarchic thesis was that several of Europe’s finest universities were founded, during the Italian Renaissance, by “secession”. Faculty thwarted by rigid state or clerical bureaucracy simply quit, taking with them dozens of their students, and created self-directed places like the University of Florence.

Continue readingThe Prison and its Past

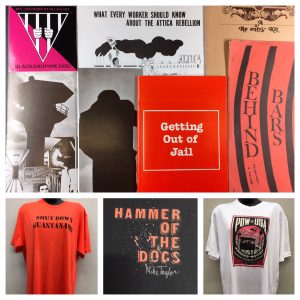

On display at the UConn Archives Gallery in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center from March 20 – May 31, 2019, an exhibition of research collections on incarceration. Drawn from ephemera, art, and personal and political papers, this story is Illustrated with the writings of the incarcerated from inside Connecticut prisons, the state’s documentation and formation of prisons, artists’ and activists’ responses to Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp, and advocacy from inside and out. This exhibition is in conjunction with the Humanities Action Lab States of Incarceration exhibit at the Hartford Public Library, March 11 – April 18, 2019 and the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center from March 25th – April 18th, 2019.

Materials on display in the gallery were drawn from the Alternative Press Collection, Cal Robertson Papers, Thomas J. Dodd Papers, Connecticut Politics and Public Affairs Collections, and Storrs Experimental Station Records.

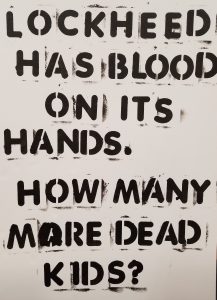

UConn Protest and the Alternative Press 1968-2018

Moments of student protest on UConn’s campus demonstrate the continuity and relevance of student activism for the Alternative Press Collection held at Archives and Special Collections. While the topics of protest often change with the political and social context of the moment, sometimes the similarities can be uncanny.

WHUS News Director Daniela Doncel reported on the student protests held during the recent university sponsored event Lockheed Martin Day:

“On Thursday, September 27, students protested the partnership between the Lockheed Martin company and the University of Connecticut due to a Lockheed Martin bomb that killed 40 children in Yemen in August, according to CNN.”

History, so the cliché goes, has repeated itself.

The circumstances of the Lockheed Martin’s presence on campus and the student protests resembled a smaller scale, and decidedly non-violent version, of the student and faculty protests of military recruiting that happened during the Vietnam War. In 1967 & 1968 students and faculty staged multiple sit-ins protesting the ties between the University of Connecticut and weapons manufacturers such as: General Electric, Olin-Mathieson, Dow Chemical, and Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation (which was sold to Lockheed Martin in November of 2015). In particular the recruitment attempts of Dow Chemical, a producer of napalm during the Vietnam War, and Olin-Mathieson drew large turn outs from students and faculty who thought that weapon manufacturers had no place trying to recruit students for jobs on the university campus. Continue reading

Deep Dives: Bringing the APC Files Collection Online

Patrick Butler, Assistant Archivist for the Alternative Press Files Collection and Human Rights Collection, is a 2018 Ph.D. graduate of the UConn Medieval Studies Program. During his time as a graduate student he worked in the UConn Archives to broaden his materials handling experience and develop skills as an archivist. He has specialized training in medieval paleography and codicology.

Over the past year I have been shepherding a project in order to make the APC Files Collection discoverable outside of a card catalog cabinet in the lobby of the UConn Archives. This collection consists of over four-thousand subject files of single issue publications, fliers, newsletters, comic books, and various ephemera relating to the underground press and political activism from the 1960s to the present. The ultimate goal of the project is to digitize and upload the entire APC Files collection to the Connecticut Digital Archives (CTDA).

At the moment I am uploading the first collection of scanned materials, which means this project, as a whole is entering into what could be considered its final phase. Final of course may belie the fact that it will require a tremendous amount of effort and continuing coordination to scan these materials in conjunction with the staff of the digitization lab at Homer Babbidge Library, without whom this project would not be possible.

This project has come with a new host of challenges for me as an aspiring archivist and seasoned academic, and has given me new opportunities to engage my more specialized research interests through different materials and addressing a broader audience as a result.

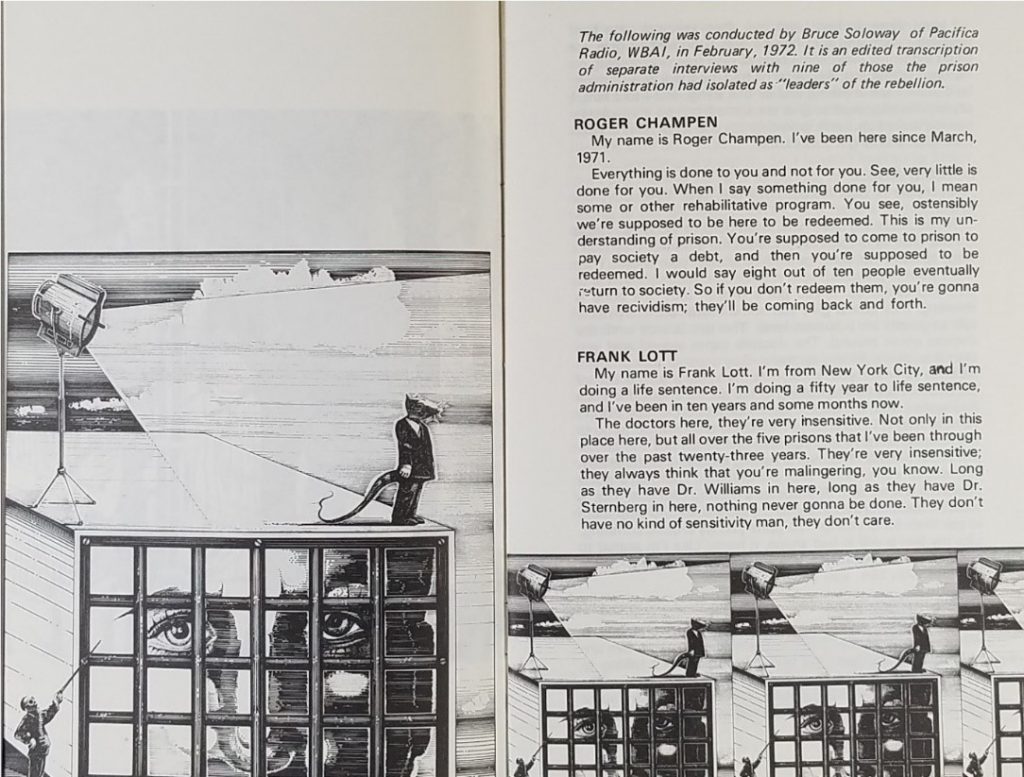

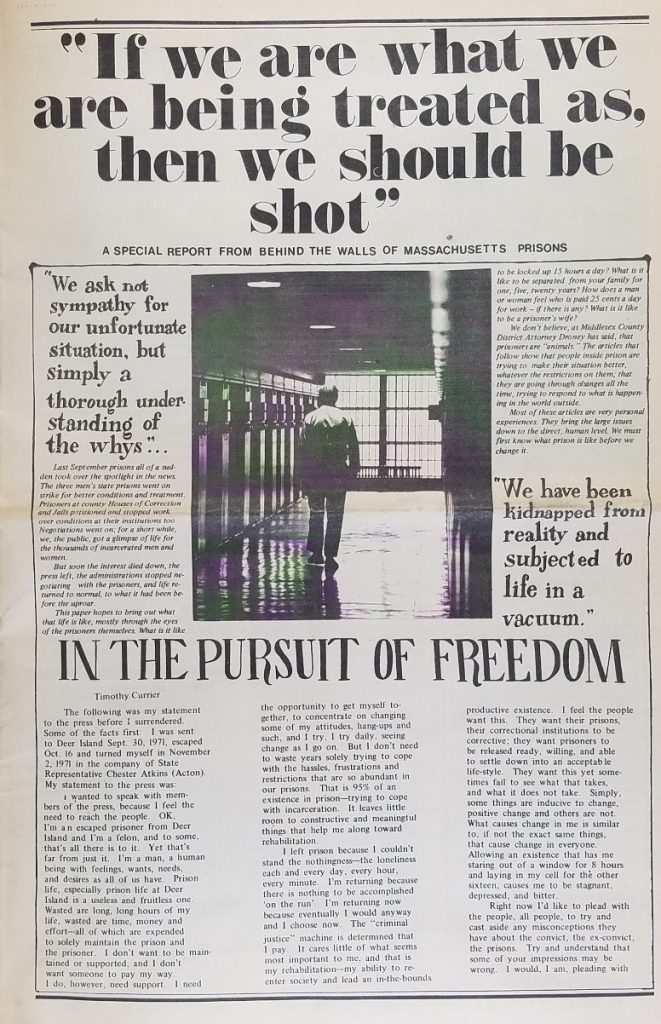

Locked Down and Speaking Up: Prison Riots, Reform, and Writing from The Alternative Press Collection

Patrick Butler, Assistant Archivist for the Alternative Press Files Collection and Human Rights Collection, is a 2018 Ph.D. graduate of the UConn Medieval Studies Program. During his time as a graduate student he worked in the UConn Archives to broaden his materials handling experience and develop skills as an archivist. He has specialized training in medieval paleography and codicology.

On August 21, 1971, African-American activist and author George Jackson took hostages in order to escape San Quentin State Prison. Five of Jackson’s hostages: three prison guards and two inmates, died in the ensuing violence. The attempted escape ended with a prison guard shooting and killing Jackson.

Two weeks later, on September 9th, 1971 approximately 1000 inmates at the Attica Correctional Facility rioted and ultimately took control of the prison facility. The inmates took 42 staff members of the facility hostage in a bid to negotiate for prisoners’ rights. During the four days of negation, prisoners made 27 demands among which included: better medical care, better sanitation, the end of racial discrimination, updated labor policies aligned with New York State law, and the end of the violent abuse of inmates by guards and prison administrators.

While negotiations with Corrections Services Commissioner Russel G. Oswald and the Attica inmates had initial success, the dialogue would ultimately breakdown when Governor Nelson Rockefeller refused to appear at the prison in a bid to help quell the riot. In the wake of the Governor’s refusal Oswald stated that they would retake the prison by force; Rockefeller agreed.

When the New York State Police had regained control of the prison 43 people were killed, 10 of which were hostages.

These two moments served as a flash point to bring prison conditions and prisoners’ rights into sharp focus during the seventies. However, part of the danger that comes from thinking of prisons and prisoners exclusively in terms of the violence is that it risks reducing the bodies of prisoners as little more than sites for violence. The aim of developing this exhibit has been to examine how materials within the Alternative Press Collections focus on the vulnerability of prisoners to the violence of the systems that shape their incarceration, how they respond to the systematic pressures that seek to justify subjecting their bodies to abuse and neglect, and the power that comes from forging communities in response to these pressures. A quote from an Attica inmate Roger Champen distills the physical, social, and bureaucratic pressure of incarceration succinctly and eloquently, “Everything is done to you, not for you.”

While the killing of George Jackson and the Attica Prison Riot serve as a starting point for the exhibition’s historical and social context, the materials in this exhibit come from a broad historical range and include a focus on documents produced by and for Connecticut Prisons. The Alternative Press Collection contains a wealth of material that document how prison communities develop and sustain themselves through creative writing, activism, correspondence, and even revolt. In order to accomplish this, I looked at the materials prisoners created while in prison, or shortly after leaving prison: newsletters, protest writing, creative writing, and original artwork. Even work published under the auspices of prison administrators allows for an avenue of expression and solidarity centered on vulnerability;

“To Be Black”

To be Black is to be seated

in Jim Crow vain

in the lonely south on a bus or

train

Because you’re Black and

your Blackness is symbolic of shame

To be Black is to hear a baby’s

screams in the rain

while be eaten by rats

in some dilapidated tenement

in Harlem

or some other place the same

To be Black is to see your mother’s

brow

after caring for another person’s home

somebody else’s child

the long lines of distress

strain

as they disfigure the make-up of her

frame

To be Black is to search in deep

despair

some other place

Freedom somewhere

Abdur Rahman (Clinton Fields) from Inside: Writings by Attica Inmates 1977-1978.

While the specific concerns of an individual piece of writing vary between violence against inmates, unjust imprisonment, political oppression, and basic human rights concerns, the language used throughout these writings, creative or otherwise is a desire for their concerns to be legible to others – to understand and to be understood. Distinct from sympathy, the specific vulnerabilities that emerged among prison writers seems to stem from a lack of acknowledgement of their embodiment as genuinely human. Almost reflexively, there is a recurrent theme to dismiss sympathy as a pressing desire among inmates. Sympathy is antithetical to the goals of these writers, a source of dismissal that does not seek to understand a fundamental connection between the prison author and the audience of the text.

The relentless desire for community, intelligibility – to not be forgotten or silenced by their isolation – makes the writings of prisoners within the Alternative Press Collection a powerful and humbling selection of materials. It holds its audience accountable for the undeniable connections that are present between individuals despite legal and societal practices of separation.

You can do two things in prison. You can be a man or you can be a robot. See, if you be a robot, you stand a very good chance of going home. But notice this, all the papers record this is a fact, that those who stay in here become submissive. When they get outside, all the things that they have inside, boil over onto society after they come back.

Roger Champen We are Attica, 1972.

The exhibition: “Locked Down and Speaking Up: Prison Riots, Reform, and Writing from The Alternative Press Collection” will be on view in the John P. MacDonald Reading Room of the Archives & Special Collections at the Dodd Research Center from June 15th – August 20th.

For more information on the Cal Robertson Papers please consult the Archives & Special Collections https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/1008

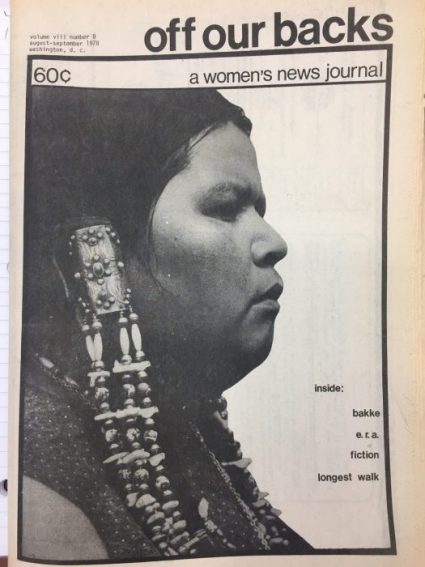

The Search and Struggle for Intersectionality Part II: Other Minorites and the Feminist Movement

Anna Zarra Aldrich is majoring in English, political science and journalism at the University of Connecticut. As a student writing intern, Anna is studying historical feminist publications from the collections of Archives and Special Collections. The following guest post is the final post in the series.

The feminist movement has long struggled with incorporating different groups’ concerns and modes of oppression into the movement. This problem was exacerbated by the multifaceted, turbulent U.S. political atmosphere that characterized the 1960s and 1970s. The differences between black and white women’s views of the movement clashed on several essential dimensions. But the issues of other minority groups were given less attention by the feminist movement, and by society in general, due to the fact that their ethnic/racial factions were much smaller than African Americans’.

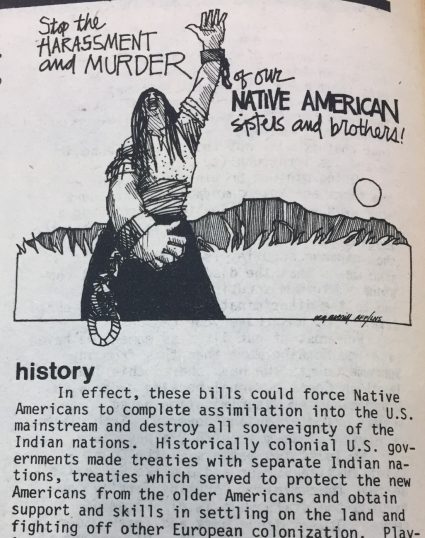

Another marginalized group that galvanized in the activist culture of the 1960s and 1970s in America were Native Americans. These men and women sought to have their tribal autonomy recognized. They were also fighting issues such as environmentally harmful mining practices on their resource-rich lands and high rates of substance abuse and poverty within their communities.

Native American women had a unique relationship with the feminist movement because the issues this minority group faced were different from those that white or black women faced, and the ethnic population of which they were a part was a severely marginalized minority. U.S. Census data from 1970 shows that a whopping 98.6 percent of the total population was either white or black/African American (87.5 percent and 11.1 percent respectively). Native Americans constituted less than .004 percent.

Native Americans were fighting for their unique political rights as well as larger environmental concerns during this period.

The March 1977 issue of “Off Our Backs” includes an article summarizing the findings of a report by the Association on American Indian Affairs (AAIA), a non-profit organization founded in 1922 to promote the well-being of Native Americans and Alaskan Natives. The report found that Native American children are placed outside of their families at a rate 10 to 20 times higher than that for non-Native American children.

The AAIA argued that this practice deprives Native American children of the ability to be raised with a proper awareness of and appreciation for their culture. This concern emphasizes the fact that Native American women who were involved in the feminist movement during this time were simultaneously combatting the United States government’s systematic efforts to diminish their independence and culture as well as the wide-spread sexism that was the feminist movement’s main concern.

Native American culture celebrates its strong connection to and appreciation of nature. When Native American tribes were forced off their lands in the nineteenth century, they were put on reservations in states like Oklahoma and South Dakota. The U.S. government later came to realize these areas were rich with natural resources such as oil and uranium.

“In the days of diminishing U.S. energy resources, the push is on to take what’s left of Indian land,” according to an article in “Off Our Backs.”

The U.S. government used environmentally hazardous practices to extract these resources, exposing people living on the land to cancer-causing radioactive materials. It also paid the Native Americans working in these hazardous mines very low wages. These practices led to outcry by Native American men and women.

In 1978, thousands of Native Americans participated in The Longest Walk, a protest organized to bring attention to threats to tribal lands pose by several pieces of proposed legislation.

“In effect, these bills could force Native Americans to complete assimilation into the U.S. mainstream and destroy all sovereignty of the Indian nations,” the article on the march said.

In the same August/September 1978 issue that covered the march, “Off Our Backs” included coverage of a conference in New Mexico that addressed the upsurge in domestic violence against Navajo women. This increase was attributed to a “pressure cooker syndrome” created by white culture: “women-battering and child abuse (were) once practically non-existent…and has now reached crises proportions.”

The attempted forced assimilation of native people into white culture created a class system that did not exist in Navajo tribal society. This led to high poverty and unemployment rates which in turn came to be correlated with high rates of substance abuse and domestic violence.

The writers draw attention to the fact that few of the speakers at the conference were from the Navajo or from any other Native American community. Calling attention to the lack of authentic representation at this conference may be an indication of the evolution of “Off Our Backs” in how it dealt with minority issues. When the paper first began in 1970, it struggled to expand their coverage to minority women’s issues, as evidenced by its problematic coverage of a black feminist group’s conference in 1974.

Similar to black women who were involved with groups like the Black Panthers, politically active Native American women were part of efforts led by men. Women of All Red Nations (WARN) was a Native American women’s group that brought attention to issues that affected their community including the displacement of their children, forced sterilization, tribal rights, resource exploitation and racism in the educational system. The group invited several Native American men to speak at a conference it held in South Dakota in 1978 as it did not “believe in the separation of men and women who were working for the same objective.” This serves as a perfect parallel to black women activists who wanted to be a part of the black and feminist movements.

Burning Cloud’s letter serves as a quintessential example of a woman’s struggle to find a way to be politically active as someone with a complex set of oppressed identities.

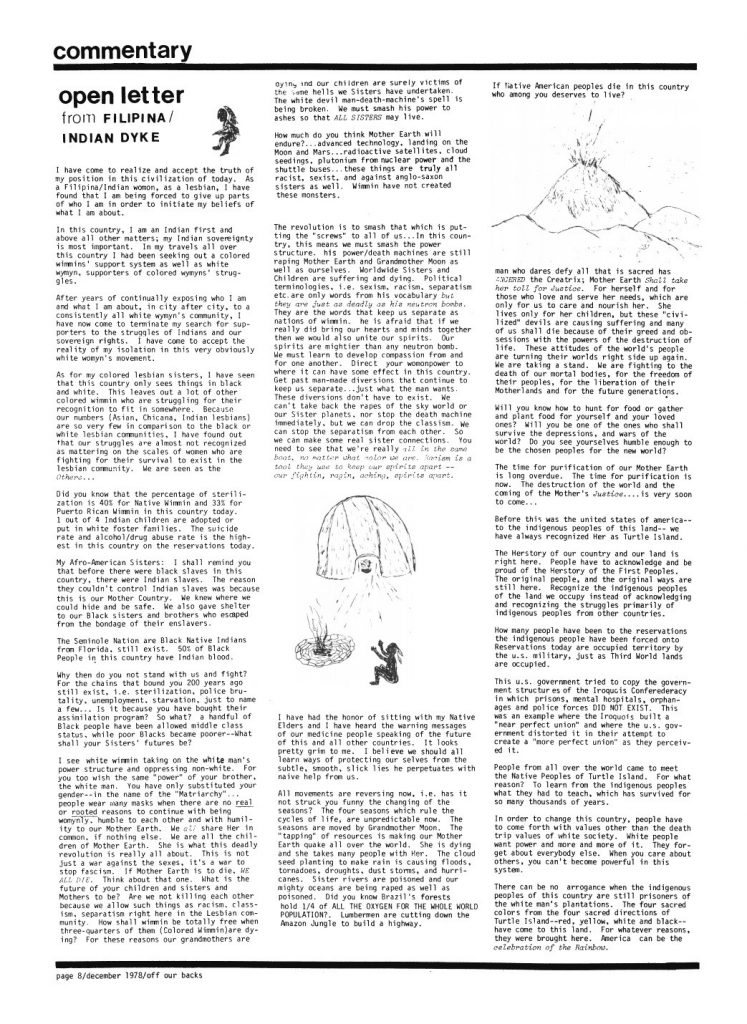

In the December 1978 issue of “Off Our Backs,” the editors printed a letter from Burning Cloud, a self-described “Filipina/Indian Dyke.” In the letter, Burning Cloud shared a sentiment common with those expressed by black women — that she was “Indian first and above all other matters.”

Burning Cloud felt she could not be both an Indian and a gay woman in society. She also expressed frustration with the fact that non-black minorities’ concerns are much more widely disregarded because there are comparatively few of them in number.

Burning Cloud’s letter included a call to action for environmental activism which, from her perspective, was something of which native people were much more conscious due to their spiritual cultural connections to the earth.

“If Mother Earth is to die WE ALL DIE. Think about that one. What is the future of your children and sisters and mothers to be?” she wrote. “Are we not killing each other because we allow such things as racism, classism, separatism right here in the Lesbian community. How shall wimmin be totally free when three-quarters of the (Coloured Wimmin) are dying?”

(Feminists took to using alternative spellings of “women” and “woman” in order to avoid using the masculine root of those words.)

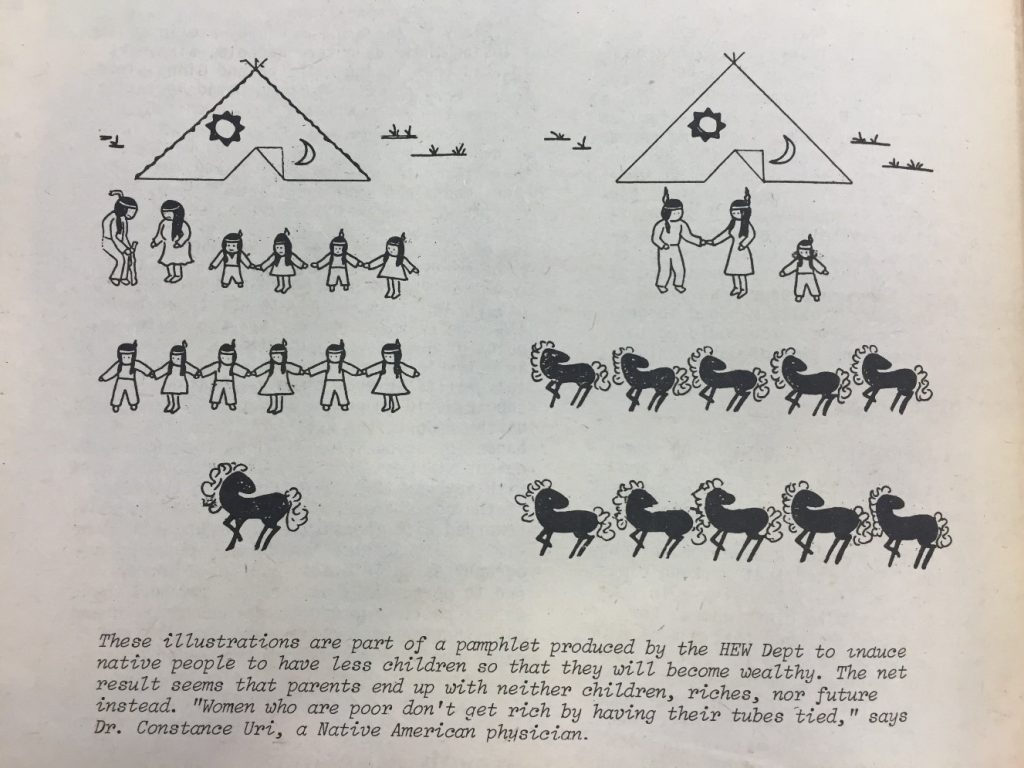

Native American women also faced the issue of forced or coerced sterilization. In “Off Our Backs” article from December 1978, WARN said that 25 percent of Native American Women were forcibly sterilized.

During this period, the United States government instituted polices of population control that targeted minority, underclass women. One third of Puerto Rican woman of reproductive age had been sterilized in 1976. This policy was veiled as a necessary method of population control that would help Puerto Rico develop economically. However, many argued that the problem was not overpopulation, rather that the available resources were concentrated in the upper echelons of society.

In her 1976 University of Connecticut Ph.D. thesis “Population Policy, Social Structure and the Health System in Puerto Rico: The Case of Female Sterilization,” Peta Henderson found that in addition to medical reasons, the law in Puerto Rico regarding female sterilization allowed for women to be sterilized or use other contraceptive methods in cases of poverty or already having multiple children. Henderson found that most sterile Puerto Rican women said they voluntarily chose to have the operation. However, she explores how this choice was corrupted by the fact that government actors worked to persuade these women that sterilization was in their best interest.

The U.S. Government put forth the idea that having fewer children was the surest path to wealth for minority women, ignoring institutional issues including racism and sexism that impeded their social mobility.

These kind of population control polices were also implemented elsewhere in Latin America.

The April 1970 issue of “Off Our Backs,” a female member of the Peace Corps who went to Ecuador said, “Providing safe contraceptives must be a part of a comprehensive health program,” Rachel Cawan said. “Most importantly, however, there must be available other emotionally satisfying alternatives to child raising.”

The prevailing feminist interpretation of these population control programs was that they masqueraded as liberating family planning alternatives when, in fact, many of these women were being coerced or forced to stop having children.

The Young Lords Party was founded in 1960. The men who founded the organization had a series of objectives including self-determination for Puerto Rico, liberation for third-world people and, problematically, “Machismo must be revolutionary and not oppressive.”

Early in the party’s history, the men in the movement did not listen to women’s ideas and concerns during meetings. These women were limited to essentially being glorified secretaries for the party according to a November 11, 1970 New York Times article.

The women in the movement soon tired of this dynamic and demanded to be taken seriously – and they succeeded. Several women were able to assume leadership positions in the party and the pillar relating to machismo was changed to one supporting equality for women. However, this victory did not mean women were automatically able to achieve true political and social equality within the party or on a larger scale.

In a subsequent issue of “Off Our Backs,” a black/Native American woman wrote a response to Burning Cloud’s letter, which had also said black people should support Native Americans’ issues, saying that: “There is a need for Dialogue, a conversation, between Indian people and Black people…We have been divided in order to be conquered, even though for many, our blood flows together.”

A theme that emerges again and again when studying the second-wave of the feminist movement is that by separating women into sects with seemingly irreconcilable differences, men have managed to prevent them from forming a powerful united front capable of combatting not only sexism, but racism and other social ills that afflict them.

-Anna Zarra Aldrich

I smell a RAT

Anna Zarra Aldrich is majoring in English, political science and journalism at the University of Connecticut. Anna is a student writing intern studying historical feminist publications from the collections of Archives and Special Collections. The following guest post is one in a series to be published throughout the Spring 2018 semester.

In February of 1970 a terrorist group took over a prominent underground newspaper in New York.

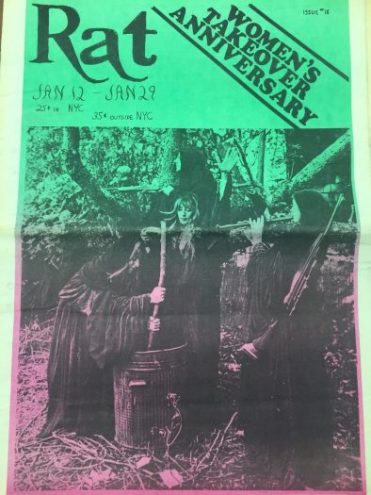

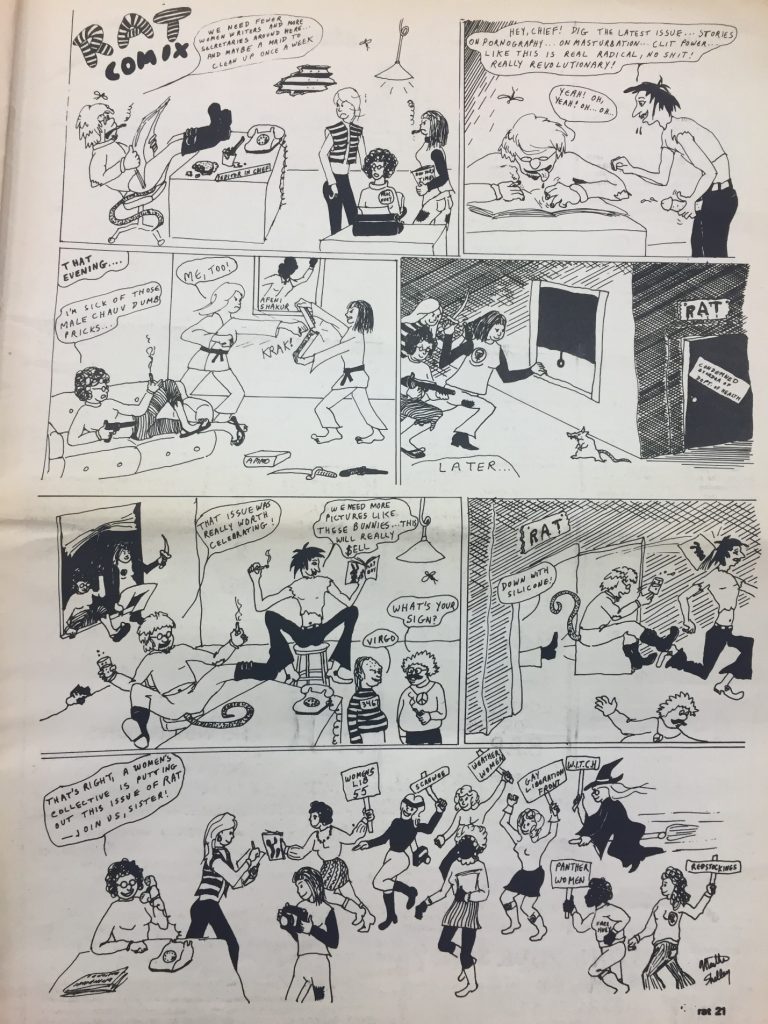

The Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell (W.I.T.C.H.), a direct-action political group, along with several other women’s groups and female “RAT” staffers took over the newspaper for what was supposed to be a single, token issue of the paper. The headline on this issue read, “Women Seize RAT! Sabotage Tales!”

This comic, published in the women’s issue of RAT illustrates the takeover which was enabled by numerous women’s groups including W.I.T.C.H.

The women’s issue featured an essay by Robin Morgan, an American writer and noted feminist activist, titled “Goodbye to All That.” The essay sharply criticizes the advertisements using photos of women that bordered on pornographic and the continual exclusion of a feminist viewpoint from the paper.

“We have met the enemy and he’s our friend. And dangerous,” Morgan wrote.

Morgan’s article rallied against the white, male domination of the radical anti-war/anti-establishment movement. She said, “Goodbye, goodbye. To hell with the simplistic notion that automatic freedom for women – or nonwhite peoples – will come about zap! with the advent of a socialist revolution. Bullshit.”

Grievances against male radicals were common among feminist writers during this period. A pamphlet written by Andrea Dworkin in 1973 titled “Marx and Gandhi Were Liberals” stated that men permitted women to take part in their vision of the revolution so long as they kept their own demands moderated and subsumed within the male-dominated agenda.

“Liberal gestures of good will are made when we are shrill enough or when we are fashionable enough as long as we do not interfere with the ‘real revolution.’ Increasingly we understood that we are the real revolution,” Dworkin wrote.

The January 25-February 9, 1970 issue of “RAT,” the last one published by the male editorial staff, included numerous articles on pornography and masturbation. An article by Uncle Leon Gussow argued that pornography gives young men unrealistic views of sex and creates a separation between him and the act of sex. The women who worked at “RAT” took issue with how this topic was approached by the male staff; they believed this article, and the paper in general for quite some time, promoted pornography. Many women saw pornography as problematic as it often portrayed violence against women and this became a major issue in the women’s liberation movement.

The women also disliked the fact that the tongue-in-cheek titles that appeared on the masthead of each issue were often demeaning and stereotypical to women, referring to them as “princess” or “muffin purchaser.”

After the women of “RAT” published their issue they were loath to return control to the men who had been running the paper since its inception in 1968. So they didn’t.

In the next issue, the women still made up the entirety of the editorial staff, but some men came back temporarily as production staffers to ease the transition. In a letter to the readers, the editors said they were trying to “work it out” with the men. All male staff members were eventually asked to leave the paper and control remained in exclusively female hands.

A letter to the readers from former editor Paul Simon explained that after a “stormy” meeting between the men and women of the paper, it was decided that the paper would continue to be published by the women.

The takeover at “RAT” inspired women working at other papers across the country to follow suit. In the April 4, 1970 issue of “Vortex,” an underground paper published out of Lawrence, Kansas, W.I.T.C.H. wrote a letter to the paper saying, “you are a counterfeit left male-dominated cracked-glass-mirror reflection of the American nightmare.” The letter said the group was preparing to organize a boycott of the paper.

This letter was published in the issue of the paper following issue on the women’s liberation similar to the one that initiated the permanent takeover of “RAT.” In September of that same year, “Vortex” moved to a collective model of publication. This altered the existing editorial structure at the paper and gave women a larger say in its production beyond their single issue which, unfortunately is not available at the Dodd Center Archives.

“RAT” continued its coverage of issues like the Vietnam War and the trial of the 21 members of the Black Panther Party who were charged with coordinating attacks on a series of New York City buildings. However, the new editors made sure to make women’s issues and the accomplishments of female activists more prominent.

They featured letters from Mary Moylan, one of the Cantonsville Nine, a group of activists who burned draft files to protest the war. Moylan went underground, hiding from the authorities for a period and her letters about her time underground were published in “RAT” and other publications like the women-run “Off Our Backs.” “RAT” also featured articles about women’s role in the Israeli-Palestine conflict.

In March of 1971, the paper changed its name to the Women’s LibeRATion.

One thing the women sought to dissemble with their takeover was the hierarchical structure that had allowed men to squelch their voices for so long. This led them to establish a newsroom that was much more free-flowing and less rigidly structured. In a letter to the readers, the editors describe the RAT work collective’s meetings as “un-chaired and chaotic.”

The paper continued publishing with relative consistency through 1972 and then stopped abruptly for several months. Then, in April of that year, a newsletter came out.

The single printed sheet explained to readers that the fate of “RAT” was in limbo due to internal fractionalization. A group of six black gay women had seized control of the paper after airing their grievances against the white feminist viewpoint that had been almost exclusively featured by the paper.

The black women writing the article said there were too many fundamental misunderstandings between the white and third-world women in the movement to be reconciled into a cohesive vision in which all voices could be heard.

The letter published on the back cover of the single-sheet issue asked readers to respond with feedback and monetary donations to support the continuation of the publication

The newsletter closed with a request for feedback from readers, “Your responses will determine the outcome of the almost defunded ‘RAT;”. The paper also asked for monetary donations to help keep the presses running.

Unfortunately, it appears these women were unable to keep the paper afloat either due to a lack of interest or lack of funds.

The downfall of “RAT” showcases the lack of an understanding of the idea of intersectional feminism during this time. Perhaps it also demonstrates a lack of will on the part of white feminists to create connections with minority women and engage in meaningful dialogue to understand their issues. Minority voices were not generally included in the more-prominent feminist outlets, or if they were given a space, it was still through the good graces of white editorial staffs. This is an unfortunate truth that the feminist movement continues to grapple with today.

-Anna Zarra Aldrich