[slideshow_deploy id=’9526′]

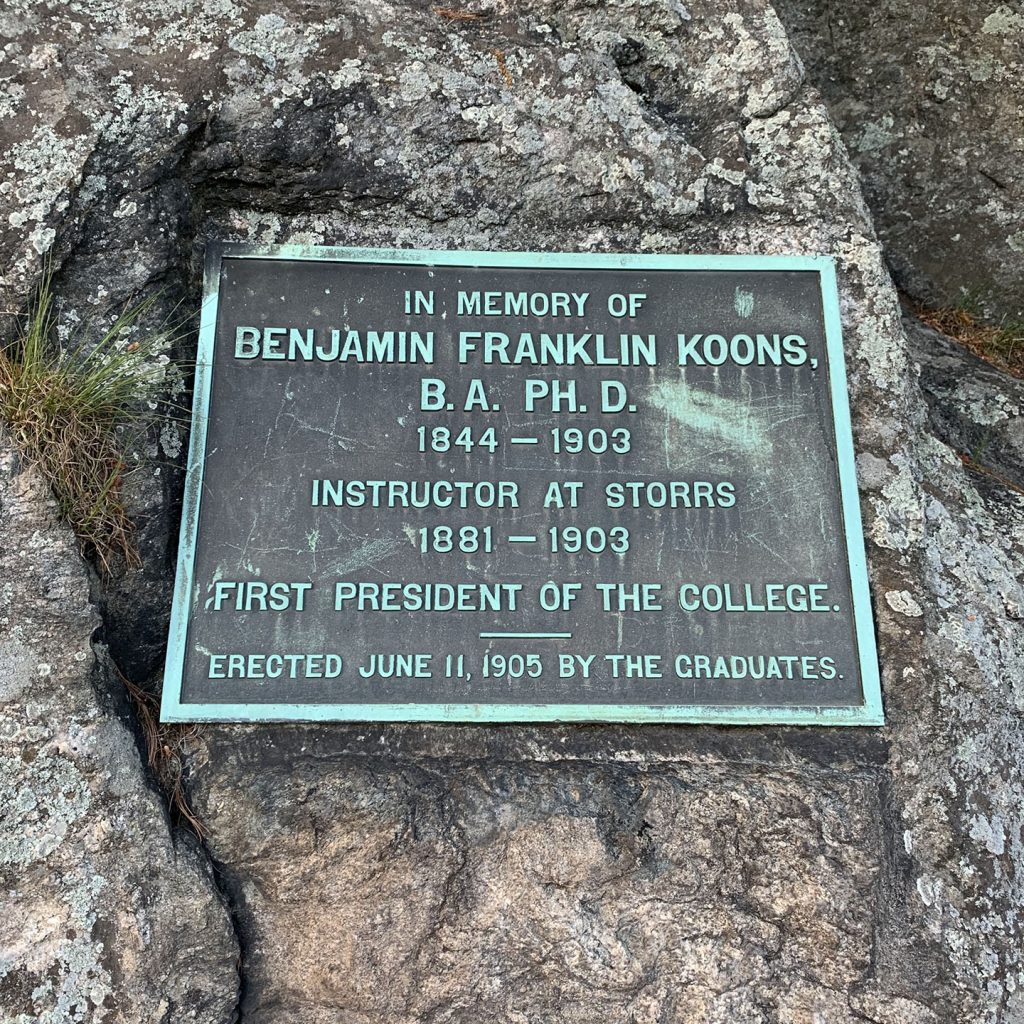

Various forms of student government date back to when the University of Connecticut was known as the Storrs Agricultural College, from 1881 to 1899. Since the inception of the first version of student government at Storrs its purpose has been to act as a representative of the student body and to advocate for various causes on behalf of its constituency. Some of these causes have included creating and funding other student organizations and petitioning the administration for civil rights reforms.

In the 1896 inaugural edition of the S.A.C. Lookout, the first student run student newspaper, two separate organizations, the “Students’ Organization” and “Council,” were cited as the structures of student government. The former acted as the executive wing and the latter as a senate, and lasted until the early 1920s.

The first big change in student government occurred in 1923 when the Council (by this time referred to as the “Students’ Council”) became the Student Senate. This body remained similar to its predecessor until 1933, when all student representative power was centralized in the Senate, forming the Associated Student Government (ASG). The Students’ Organization existed alongside the Senate until the reorganization of 1933, when both merged to become ASG. The structure of this new government included Legislative, Executive, and Judicial branches, but these were not independent of each other, as the Elected Vice President of ASG automatically became the Chairman of the Student Senate.

A Women’s Student Council emerged at the end of the 1910s, and this body existed for over 60 years in various forms, either as the Women’s Student Government or Associated Women Students. Its end in the early 1970s coincided with the founding of the Women’s Center at UConn, along with the merging of the departments of women’s and men’s affairs.

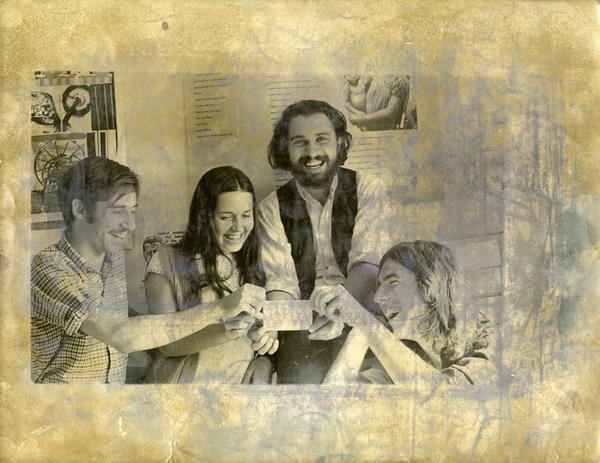

ASG existed from its creation in 1933 until its dissolution in 1973, which took multiple years to take effect. One of the catalysts for ASG’s demise was its presidential election in 1972, where the student body, fed up with their representatives, elected “Bill X. Carlson” as a write-in option. The catch was that Carlson was a fictitious person. Thus, runner-up Dave Kaplan assumed the presidency but resigned within the year, as calls for a Constitutional Convention strengthened. By the next year, ASG was replaced by the Federation of Students and Service Organizations (FSSO), which had been selected from a list of options proposed by various students. Its structure included an eight-person Central Committee that held absolute jurisdiction, with Primary and Secondary committees under it.

The FSSO lasted a mere seven years, as a new Constitutional Convention was called at the end of the decade, leading to the inception of the Undergraduate Student Government (USG). The transition from FSSO to USG was far smoother, as the FSSO was not fully dissolved as ASG was. The convention led to a transition from FSSO to USG that circumvented the total absence of student government that had occurred in the interim between ASG and the FSSO.

USG has continued as the student government of UConn since 1980. Currently it consists of Legislative, Executive, and Judicial Branches, made up of the Senate, the President and the Advocacy Committees, and the Judiciary respectively.

Researchers interested in UConn’s more than a century of student government will find a plethora of resources on the subject in Archives & Special Collections. From 1944 onward, the Archives has the records kept by the ASG, FSSO, and USG. Student government resources generally include student publications, presidential files, photographic prints, and more. Among some of the Archives’ relevant collections are:

University of Connecticut, Undergraduate Student Government Records. This collection is split into four series: Associated Student Government (ASG) records from 1944-1973, Federation of Students and Service Organizations (FSSO) records from 1973-1981, Undergraduate Student Government (USG) records from 1980-2008, and the records of the Inter-area Residence Council from 1970-1982. While the USG records within the collection end at 2008, the Archives has Minutes and Agendas from 1985 up to the present day. The records include Constitutions, Committee Minutes, reports, Election data, correspondence, speech transcripts, documentation of Constitutional Conventions, and more. The finding aid to the collection can be found at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/721.

University of Connecticut Photograph Collection. This collection includes over 800,000 photographic prints, slides, negatives, and postcards. For content related to Student Government at UConn, look for sections of this collection relating to Student Activities. The finding aid to the collection can be found at https://archivessearch.lib.uconn.edu/repositories/2/resources/958.

The Daily Campus and other student publications. Student publications have gone by several titles before its current iteration, including the Storrs Agricultural College Lookout, the Connecticut Agricultural College Lookout, the Connecticut Campus and Lookout, the Connecticut Campus, and the Connecticut Daily Campus. Throughout the years, the paper has reported on the affairs of student government at UConn, dating back to its very first issue in May 1896.

You can find issues of the Daily Campus and its predecessors, from the Storrs and the regional campuses, dating from 1896 to 1990, in the digital repository at http://hdl.handle.net/11134/islandora:campusnewspapers

Articles of particular interest include:

• S.A.C. Lookout, December 1, 1898, “Student Government,” which outlines the function and structure of the Students’ Organization, as well as the Students’ Council: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:860167952

• Connecticut Campus, April 10, 1934, “Committee Formulates Plans For Election May 1,” Associated Student Government and Women’s Student Government Elections are both referred to: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:860217304

• Connecticut Daily Campus, September 14, 1976, “Finch outlines FSSO semester projects, goals,” where FSSO Chairman William Finch explained the objectives of the FSSO at the beginning of the semester: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:860294245

Nutmeg, the student yearbook. Nutmeg originated in 1915 and includes photographs and descriptions of different student governments at UConn through the years. Issues from 1915 to 1999 are available in the digital repository beginning at: http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:02653871

Of particular interest:

• 1934 Nutmeg’s entry on the reorganization of the Student Senate and the origins of the student government, at http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:02653871 (page 146) and a photograph of the 1933 Women’s Student Government on page 138.

• The 1973 issue has information about the dissolution of the Associated Student Government, at http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:859981755

• 1979 Nutmeg’s entry on the Federation of Students and Service Organizations, featuring a Connecticut Daily Campus article entitled “FSSO committee dumps clubs,” detailing the FSSO’s recall of over $30,000 from student organizations, at http://hdl.handle.net/11134/20002:859981740

University of Connecticut, President’s Office Records. This collection includes the records of all of UConn’s Presidents, starting with Solomon Mead in 1881 and currently ending with Susan Herbst, whose tenure in office ended in 2019. The collection is updated as records are periodically transferred by the President’s office for permanent retention in the Archives. While this is not a chiefly important source of information on UConn’s student government organizations, small mentions may be found in many of the Presidents’ documents.

This post was written by Sam Zelin, formerly a UConn undergraduate student in the Neag School of Education who was a student assistant in Archives & Special Collections.