One might think that after teaching at UConn for 33 years, writing some 20 books and scores of journal articles on the historic restoration and preservation of landscapes, and creating master plans for such national landmarks as Jefferson’s Monticello and Washington’s Mount Vernon – not to mention having those plans placed in the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Gardens and Landscapes – Professor Emeritus Rudy J. Favretti, might be ready to sit back and rest on his proverbial laurels. That would be a reasonable assumption, if one didn’t know him.

Blessed with an abundance of energy and a “planning gene,” Favretti, 81, says much of his intellectual spadework has been done at the UConn Libraries.

Rudy Favretti in the Archives & Special Collections Reading Room.

“I use the library a lot – the art and history sections and interlibrary loan,” he notes. I have found the staff in all of these sections extremely helpful, in general, and especially as I search for odd and obscure material that is not readily available. It’s a great place!”

After earning his undergraduate degree from UConn in plant science, the Mystic, Connecticut native went on to earn advanced degrees in horticulture, landscape architecture, and regional planning from Cornell and the University of Massachusetts. At UConn, he served as an extension garden specialist and extension landscape architect from 1955-1975, and taught landscape architecture here from the late 1960s to 1988, developing the accredited landscape architect program, retiring when he was 55. During his career, he completed about 700 individual and collaborative design, master planning, and preservation projects.

In 2011, no longer actively engaged in design work, he agreed to share his personal papers with the Smithsonian. There, one can find the lion’s share of his research and work – 4,000 slides, drawings, and notes totaling some 27 linear feet. Having it housed there is a “huge honor,” he says. Some of his work can also be found in UConn’s Archives & Special Collections

Favretti made the restoration and preservation of gardens and landscapes his life’s work, appreciating not only their aesthetic value, but their value as a lens through which to view a person’s life and times. Several years ago, he shifted his focus from gardens directly to people, specifically those who lived in Mansfield, his home for close to six decades. To date, he’s written about Wormwood Hill (in concert with his friend and longtime resident of the area, veteran UConn administrator, the late Isabelle Atwood), Mansfield Four Corners, Mansfield Center (as co-author) and the Gurleyville/Hanks Hill area, which is a tribute to his friends, fellow UConn faculty members, the late Annarie and Fred Cazel, Gurleyville residents themselves, who had done some research on the area, but who died before writing a book. The couple’s bequest to the Mansfield Historical Society will allow more regional histories to be published.

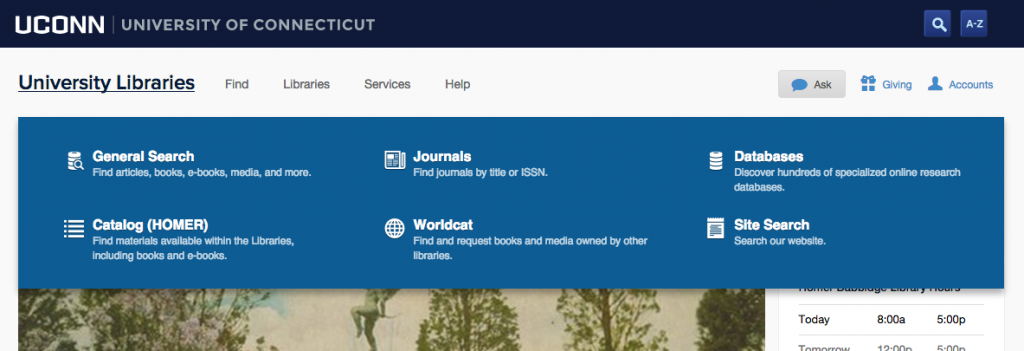

Research for these histories, as well as for other undertakings including his keynote address in 2012 on the University’s iconic “Great Lawn,” has made Favretti a familiar sight in Archives & Special Collections and Homer Babbidge Library.

“Even though I’ve been on this campus for over 60 years, I didn’t realize that in 1908 President Charles L. Beach had hired prominent landscape architect Charles Lowrie, a founding member of the American Society of Landscape Architects, to help plan the placement of the buildings surrounding the Great Lawn. The plans are here at the Dodd Center. I didn’t know they existed until I began researching the Great Lawn. Just because you retire, your academic life doesn’t end,” he contends.

He is also currently at work on a book commemorating the 50th anniversary of Joshua’s Tract Conservation and Historic Trust, the largest such trust in Northeastern Connecticut, which he helped to found and whose papers are housed in UConn’s Archives & Special Collections. After completing that volume, he intends to finish his research into Mansfield Depot and produce yet another local history.

“Over the years, I’ve done all this research into local history. What would happen to it? That’s what I’m doing now – transposing it into books, which I’m enjoying very, very much.”

His enjoyment today extends well beyond Mansfield. While he continues to tend his own gardens and remain active in the greater Mansfield community, he and his wife, Joy, regularly savor performances at the Metropolitan Opera. While in New York, they stay with their son, Giovanni, keeping tabs on the garden he designed for Giovanni’s townhouse. Other pleasures come from following the activities of his two daughters, Margaret, a high school history teacher in Scarsdale, NY, and Emily, an artist in Chicago.

What hasn’t the energetic octogenarian done? “I’ve always wanted to write a novel. I’ve written so many straight-forward subject matter things like extension bulletins; when you write a novel, it’s about people.”

His training as a landscape architect, which required him to notice detail, should serve him well. “I can go to a cocktail party, come home, and describe what everyone was wearing. That kind of detail would be good for writing a novel,” he observes with a smile.