Ken Best, UConn Communications

Re-posted from UConn Today

February 21, 2018

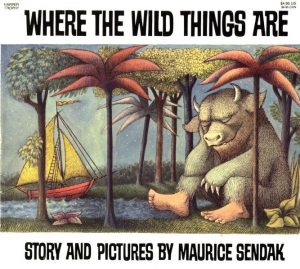

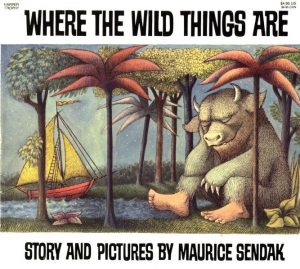

Cover of ‘Where the Wild Things Are,’ ©1963 by Maurice Sendak, copyright renewed 1991 by Maurice Sendak. Used with permission from HarperCollins Children’s Books.

The finished artwork for his published books, and certain manuscripts, sketches, and other related materials created by Maurice Sendak, considered the leading artist of children’s books in the 20th century, will be hosted and maintained at the University of Connecticut under an agreement approved today by UConn’s Board of Trustees.

The Maurice Sendak Foundation will continue to own the artwork and source materials for books such as Where the Wild Things Are, In the Night Kitchen and Outside Over There, which will serve as a resource for research by students, faculty, staff, scholars and the general public through the Department of Archives & Special Collections in the UConn Library. The housing of The Maurice Sendak Collection at UConn is being supported by a generous grant from The Maurice Sendak Foundation.

“You would only have to spend an afternoon with Maurice to know that he was the ultimate mentor and nurturer of talent,” says Lynn Caponera, president of The Maurice Sendak Foundation. “He profoundly admired UConn’s dedication to the art of the book, both in its collections and in its teachings. We, the friends who he entrusted to carry on his legacy through the Foundation, couldn’t be more pleased with this exciting collaboration.”

Archives & Special Collections includes the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, which contains 120 archives of notable authors and illustrators of children’s literature native to or identified with the Northeast and East Coast of the United States. The collection, established in 1989, preserves every aspect of children’s book production – from the initial correspondence to preliminary drawings, finished art, dummies, mechanicals, proofs, galleys, and manuscripts.

Imagine now opening up students to the world of one of the most celebrated creators of visual literature for children’s picture books … and walking across campus to take part in what amounts to a private master class with Maurice Sendak.— Cora Lynn Deibler

Significant holdings in the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection include the archives of leading authors and illustrators who have won major honors such as the Caldecott Medal, Caldecott Honor, John Newbery Medal, and Laura Ingalls Wilder Award, among others. It also contains “The Billie M. Levy Collection of Maurice Sendak” of more than 800 monographs written and illustrated by Sendak, along with realia manufactured for children, such as promotional toys, games, animals, and other items that relate to Sendak’s stories and characters.

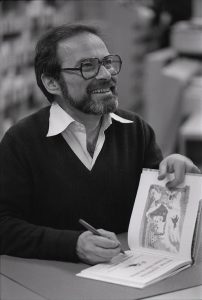

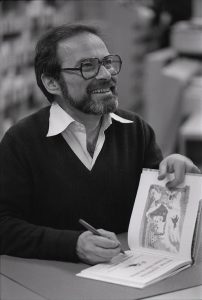

Renowned author and illustrator Maurice Sendak signs books at the UConn Coop bookstore on April 28, 1981. (Jo Lincoln Photo, courtesy of Archives & Special Collections, UConn Libraries)

“Maurice Sendak created books that will live forever. His work changed the course of children’s literature in the twentieth century,” says Katharine Capshaw, professor of English and president of the Children’s Literature Association. “From Where the Wild Things Are to the Nutshell Library [series] to We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy,Sendak’s books connect profoundly to children’s inner fears and vast resourcefulness. He treated young people with respect, valuing their creativity and sense of ethics, and his work illuminated the joy and mystery of the imagination.”

Capshaw notes that The Maurice Sendak Collection will be an invaluable resource for UConn undergraduate students in English, Creative Writing, Art and Art History, the Neag School of Education, and Psychology, as well as our graduate students and visiting scholars.

“Given Sendak’s life as a Connecticut resident and his longstanding connection to the University of Connecticut, his work has found an apt home,” she adds. “They will enrich Connecticut students and the intellectual and aesthetic life of our community.”

Sendak lived in Connecticut and supported UConn for many years, speaking to the children’s literature classes of Francelia Butler, professor of English, in the 1970s and 1980s, and supporting the legacy of James Marshall, author of the “George and Martha” books. The James Marshall Fellowship at UConn is awarded biennially to a promising author and/or illustrator to assist with the creation of new children’s literature. In 1990, Sendak delivered a commencement address at UConn and received an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts.

Sendak’s children’s books have sold more than 30 million copies and have been translated into more than 40 languages. He received the 1964 Caldecott Medal for Where the Wild Things Are and is the creator of such classics as Higglety Pigglety Pop! and the Nutshell Library. He received the international Hans Christian Andersen Medal for Illustration in 1970, Laura Ingalls Wilder Award from the American Library Association in 1983, and a National Medal of Arts in recognition of his contribution to the arts in America in 1996. He also received the first Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, an annual international prize for children’s literature established by the Swedish government in 2003.

After his death in 2012 at the age of 83, The New York Times said Sendak is “widely considered the most important children’s book artist of the 20th century, who wrenched the picture book out of the safe, sanitized world of the nursery and plunged it into the dark, terrifying, and hauntingly beautiful recesses of the human psyche … [His] books were essential ingredients of childhood for the generation born after 1960 or thereabouts, and in turn for their children.”

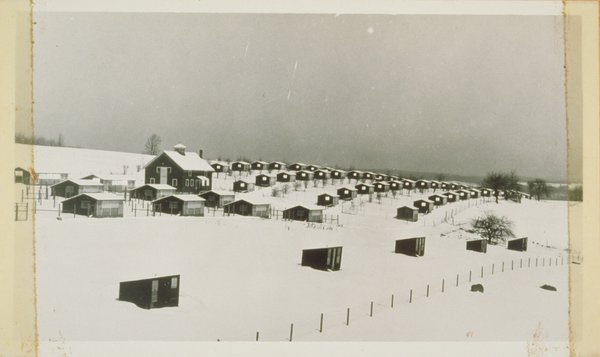

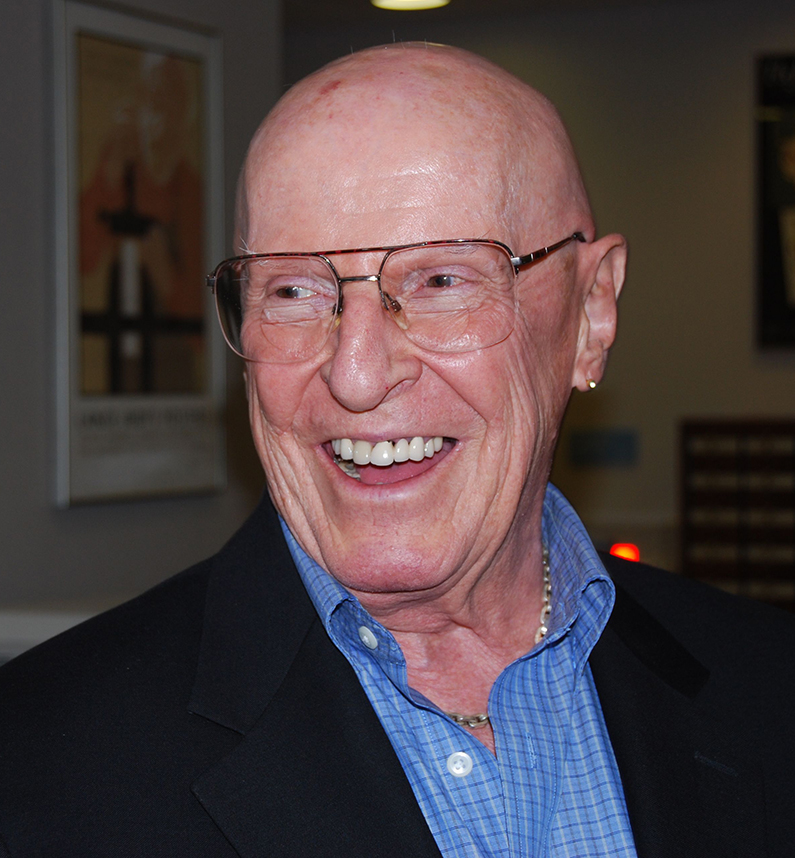

Maurice Sendak receives an honorary degree from then-President Harry Hartley during Convocation on Sept. 5, 1990. (Archives & Special Collections, UConn Libraries)

“The availability of Maurice Sendak’s work to students, faculty, and the community, as part of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, is an incredible gift and opportunity,” says Cora Lynn Deibler, head of the Department of Art and Art History and a professor of illustration.

She says that Archives & Special Collections allows unprecedented access to anything and everything in their holdings, and that faculty members take advantage specifically in Illustration and Animation because it provides “an important window into the working worlds of some of the most elite, accomplished visual storytellers of our time.

“Imagine now opening up students to the world of one of the most celebrated creators of visual literature for children’s picture books … and walking across campus to take part in what amounts to a private master class with Maurice Sendak. As you pore through the work, you will be receiving a one-on-one tutorial in excellence in the form – from creativity and concept, through design and execution. Sendak’s work housed here is such an incredible gift for us all. We could not be more fortunate.”

It would be difficult to find someone more dedicated to the UConn Library’s Archives & Special Collections than Richard Schimmelpfeng. Perhaps it is because of the solid foundation he built beginning with the Special Collections Department after his arrival in 1966. But more likely it is because of his dedication to the collections after his retirement in 1992. Mr. Schimmelpfeng began volunteering in the Archives the day after his retirement and was a daily staple until his recent illness a few months ago. In a March, 2005 article he stated “I intend to continue as a volunteer until either I fall over, am dragged out, or told to quit,” he quips. “I figure I’ve got about 15 more years to go.” We estimate that he worked more than 15,000 volunteer hours over 20+ years. As Norman D. Stevens, Emeritus Director of the UConn Library says in his obituary below, “his fifty years of service to the University of Connecticut is perhaps unsurpassed.”

It would be difficult to find someone more dedicated to the UConn Library’s Archives & Special Collections than Richard Schimmelpfeng. Perhaps it is because of the solid foundation he built beginning with the Special Collections Department after his arrival in 1966. But more likely it is because of his dedication to the collections after his retirement in 1992. Mr. Schimmelpfeng began volunteering in the Archives the day after his retirement and was a daily staple until his recent illness a few months ago. In a March, 2005 article he stated “I intend to continue as a volunteer until either I fall over, am dragged out, or told to quit,” he quips. “I figure I’ve got about 15 more years to go.” We estimate that he worked more than 15,000 volunteer hours over 20+ years. As Norman D. Stevens, Emeritus Director of the UConn Library says in his obituary below, “his fifty years of service to the University of Connecticut is perhaps unsurpassed.”